The Pittsburgh Pirates Go to the Movies

This article was written by Ron Backer

This article was published in The National Pastime: Steel City Stories (Pittsburgh, 2018)

Small-market teams often complain about the unfairness of baseball’s financial structure, contending that teams in large markets have disproportionate access to money to spend on players, giving them an unfair competitive advantage. Big-market teams disagree. But when it comes to the movies, there can be no argument. At the cinema, big-city teams such as the New York Yankees, Brooklyn Dodgers, Boston Red Sox, and Chicago Cubs have disproportionately dominated teams from smaller markets, with one important exception: the Pittsburgh Pirates. The Pirates have appeared in so many movies that they actually rival the Yankees in silver-screen dominance. This article will look at the many times the Pittsburgh Pirates have gone to the movies.

ANGELS IN THE OUTFIELD (1951)

The most famous film to feature the Pirates involves an eight-year-old orphan, Bridget White, who has been praying for the hapless Pirates and their unsuccessful manager, Guffy McGovern, resulting in the Archangel Gabriel sending an aide, along with his heavenly choir of former baseball players (the Heavenly Choir Nine), to assist the Pirates during their games, resulting in the Pirates playing for the pennant on the last day of the season. Much of the film was shot in Pittsburgh, particularly in Forbes Field, the home of the Pirates from 1909 until the ballclub moved into Three Rivers Stadium in 1970 and began to share the new multi-sports field with the Pittsburgh Steelers.

Angels in the Outfield is a tribute to the famous ball yard, with its ivy-covered walls (and no advertising on the walls), the scoreboard in left field in which the numbers were inserted by hand, a center field so deep (457 feet) that the batting cage was placed there during the game, the roofs of the Carnegie Library and Carnegie Museum visible from beyond the left-field wall, and the Cathedral of Learning of the University of Pittsburgh seemingly bending over so that it can get a better view of the action from its perch outside the bleachers down the left-field line. The film also contains cameos from famous Pirates players. Pie Traynor, the Hall-of-Fame third baseman and former manager of the Pirates, has a brief moment as a bullpen coach, and then-current outfielder Ralph Kiner hits a home run in the film.

In 1951, when MGM had to decide which major-league team most needed the help of angels to compete, the choice of the Pirates must have been easy. While the team had the presence of Kiner, the National League leader in home runs for seven consecutive seasons starting in 1946, not much else was going well for the team after the end of World War II.1 In fact, from 1946 to ’57, the Pirates finished in the top half of the National League in only one year, and that was a fourth-place finish in 1948. In 1950, the year before Angels in the Outfield was released, the Pirates finished in last place, 33½ games out of first. The Pirates would go on to lose over 100 games in 1952, ’53, and ’54. In two of those years, the team finished more than 50 games out of first place.2

Of course, as bad as the ’50s Pirates were, they were never as bad as they are characterized in Angels in the Outfield. If the film were to be believed, there were occasions in when a Pirates player rounded second and then decided to go back to first, causing a head-on collision with another runner; a fielder got hit in the head by a pop-up; three Pirates runners ended up on third base at the same time; and Pittsburgh lost a game to Cincinnati 21–2. All of those incidents are examples of cinema exaggeration for the sake of comedy. Nevertheless, the travails of the ’50s Pirates were so well known at the time that in the classic 1954 film On the Waterfront, which involves a New Jersey dock strike and has nothing to do with Pittsburgh or baseball, a character complains that his coat is full of more holes than the Pittsburgh infield.

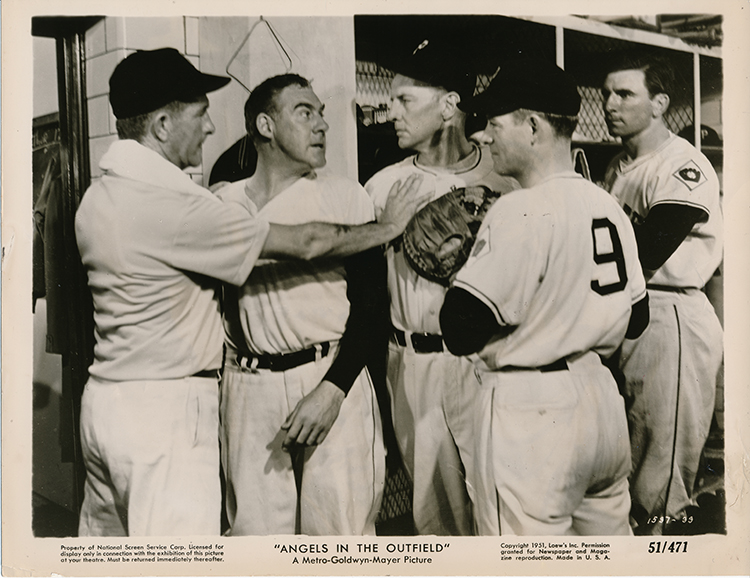

After another Pittsburgh Pirates’ loss early in Angels in the Outfield (1951), before the angels arrive to help the cellar dwellers, manager Guffy McGovern (Paul Douglas), second from the left, has an argument with pitcher Saul Hellman (Bruce Bennett). (PUBLICITY STILL)

CHASING 3000 (2007)

It was the last week of September 1972 and the baseball world was excited about the possibility that Roberto Clemente would get his 3,000th hit. Two teenage Pittsburgh natives and huge Roberto Clemente fans, Mickey and Roger, have recently moved to California because of Roger’s health problems. When their mother goes out of town on a business trip, Mickey and Roger decide to drive the family car back to Pittsburgh to see, in person, Clemente reach the 3,000-hit plateau.

Chasing 3000 is primarily a road movie about Mickey and Roger’s eventful trip back to Pittsburgh, but baseball and Pittsburgh are the themes throughout. Mickey and Roger constantly discuss Clemente as archival footage of Clemente hitting, catching, and throwing is shown to the viewer. There are lots of Pittsburgh references in the film, such as Isaly’s chipped ham sandwiches, Clark candy bars, and a hot dog shop known as “The Dirty O.”

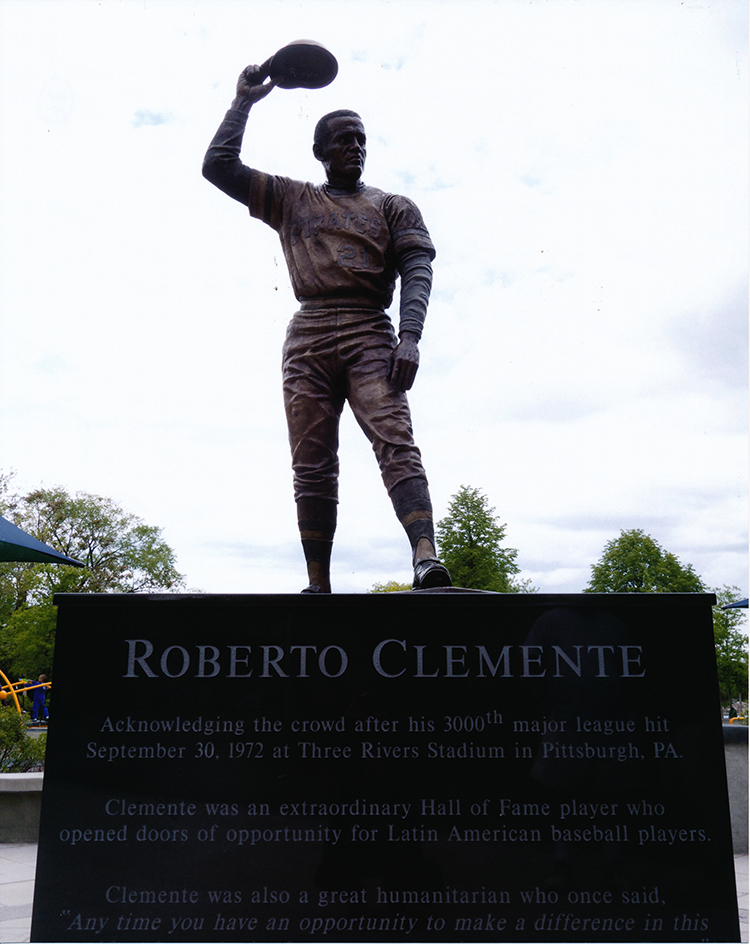

It is not giving anything away to disclose that despite the travails during their road trip, Mickey and Roger do get to Pittsburgh by the end of the movie, just in time to see The Great One achieve his great accomplishment. The moment occurred on September 30, 1972, at Three Rivers Stadium during a game between the Pirates and the New York Mets. In the bottom of the fourth inning, Clemente, in his second at-bat of the day, smacked a line drive to left-center field. The ball hit off the wall on one bounce. Clemente ended up on second base with a double. It was his 3,000th career hit, and as the scoreboard flashed on that day, “Roberto is now one of 11 players in major league history to get 3000 or more hits.”3 Well-known footage of Clemente reaching the milestone is incorporated into the new footage shot for Chasing 3000, making it appear that Mickey and Roger are really in Three Rivers Stadium in 1972, despite the fact that the film was shot many years after Three Rivers Stadium had been demolished.

The story of the film is told in retrospect by a grown-up Mickey to his two teenage children, while they are on their way to PNC Park for Roberto Clemente Day. Thus, at the end of the film, there are shots of PNC Park from the Clemente Bridge and shots of the Clemente statue situated outside the stadium.

This statue of Roberto Clemente in Roberto Clemente State Park in the Bronx, New York City, memorializes Clemente’s pose on second base in Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh on September 30, 1972, after getting his 3,000th career hit. (COURTESY OF EMMA BACKER)

42 (2013)

The second film biography of Jackie Robinson dramatizes three years of Robinson’s life, 1945 (when he was playing in the Negro Leagues with the Kansas City Monarchs), 1946 (when he was playing in the International League with the Montreal Royals), and 1947 (when he was playing in the National League with the Brooklyn Dodgers). Through the magic of digital imagery, the major-league games in the film appear to take place in Ebbets Field, Shibe Park, Crosley Field, and Forbes Field, ballparks that had long since been demolished by the time of the movie’s release.

The second film biography of Jackie Robinson dramatizes three years of Robinson’s life, 1945 (when he was playing in the Negro Leagues with the Kansas City Monarchs), 1946 (when he was playing in the International League with the Montreal Royals), and 1947 (when he was playing in the National League with the Brooklyn Dodgers). Through the magic of digital imagery, the major-league games in the film appear to take place in Ebbets Field, Shibe Park, Crosley Field, and Forbes Field, ballparks that had long since been demolished by the time of the movie’s release.

There are two scenes at Forbes Field. The first involves a game on May 17, 1947. Fritz Ostermueller, pitching for the Pirates, deliberately throws a beanball at Robinson, hitting him in the head and knocking him down. The result is a bench-clearing argument. The second is a game on September 17, 1947, when, according to the film, the Dodgers won the pennant by winning the game on a late-inning home run by Robinson, coincidentally off Ostermueller. In fact, but less dramatically, Robinson’s home run came in the fourth inning on that day, and didn’t represent the go-ahead run.4

While the computer-generated effects work fabulously to make it appear that the games are really being played in the old ball yards, there are numerous inaccuracies when it comes to Forbes Field. For example, despite what is shown in 42, there was never advertising on or above the walls of Forbes Field; the batting cage, which was always placed during a game at the deepest part of center field, is missing in the film; the right-field stands did not wrap around the center-field wall; and the large scoreboard in left field was much closer to the left field line than is shown in the film.

There is also an ironic aspect of 42, at least in retrospect. In the film, it seems that general manager Branch Rickey’s punishment for Dodgers players who do not want to play with Robinson is a trade to the lowly Pirates. For example, pitcher Kirby Higbe, who started the 1947 season 2-0 for the Dodgers, is traded by Rickey to the Pirates because of Higbe’s unwillingness to play alongside an African American teammate.5 (Higbe can be seen disgustedly saying “Pittsburgh” as he sits on the Pirates bench watching Robinson’s movie-ending home run.) Later, in 1950, Rickey had a dispute with another owner of the Dodgers and left the organization. He then became the general manager of the Pirates, his personal banishment from the top tier of major-league baseball.6

BABE RUTH’S LAST GREAT DAY

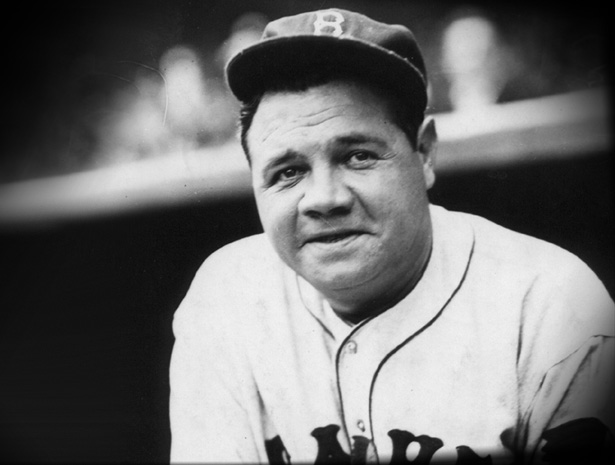

In 1935, Babe Ruth was released by the Yankees and signed with the Boston Braves, finally providing National League fans with a chance to see the Great Bambino in person on a regular basis. Unfortunately, Ruth was 40 years old that year and in ill health. His season was a personal disaster. In late May, the Braves came to Pittsburgh for a three-game series, oddly, a Thursday-Friday-Saturday series. Ruth’s batting average before the Saturday game was just .153 and he had only hit three home runs.7 And then the spectacular happened.

In 1935, Babe Ruth was released by the Yankees and signed with the Boston Braves, finally providing National League fans with a chance to see the Great Bambino in person on a regular basis. Unfortunately, Ruth was 40 years old that year and in ill health. His season was a personal disaster. In late May, the Braves came to Pittsburgh for a three-game series, oddly, a Thursday-Friday-Saturday series. Ruth’s batting average before the Saturday game was just .153 and he had only hit three home runs.7 And then the spectacular happened.

On Saturday, May 25, 1935, Ruth hit three home runs in one game. To punctuate the event, Ruth’s third home run was one of the longest he ever hit. The ball cleared the roof of the 86-foot high, double-decked right-field stands of Forbes Field and purportedly landed across the street from the ballpark. It was the first time anyone had ever hit a ball over the Forbes Field roof.8 That moment, the greatest home run hitter of his generation accomplishing such a feat so late in his career, is so amazing that both of Ruth’s sound film biographies re-create the scene.

William Bendix stars as Ruth in The Babe Ruth Story (1948). In this version of the incident, after being jeered by the crowd and a fellow teammate for his poor play, Ruth hits those three home runs in succession, turning, as the film’s narrator says, the jeers of the crowd into cheers. After then hitting a single in his fourth at-bat, Ruth removes himself from the game, permanently retiring from baseball. While that creates an interesting moment for the movie, in fact, Ruth did not quit baseball on that day, although several people, including his wife, Claire, suggested that he should. Ruth continued to play after he left Pittsburgh, appearing in the first game of a Memorial Day doubleheader in Philadelphia on May 30, then retiring a few days later.9 Oddly, the film does not even mention that Ruth’s final home run went over the right-field roof, perhaps because the film was not shot at Forbes Field and therefore there was no roof for the ball to go over. Thus, the film misses one of the most important attributes of Ruth’s last great day.

The Babe (1992), starring John Goodman as the title character, cleverly uses that same game for the conclusion of the film, allowing Babe to walk off the field while he is on top, even though that part of the story, as noted above, is fictional. Forbes Field had been torn down by 1992 and the film technology that was used in 42 to re-create the ballpark was not readily available, so again, the spectacular nature of Ruth hitting a ball over the right-field roof could not be shown in the film. Instead, Ruth hits a ball over the low, center-field seats of the playing field used in the movie and the announcer incorrectly states that it was the first ball ever hit out of Forbes Field. In addition, Ruth calls his home run shot on his first home run, something he supposedly did in the 1932 World Series in Chicago and in other games, but not that day in Pittsburgh.

Both films also omit another intriguing fact about Ruth’s last great day in Pittsburgh: Despite Ruth’s four hits that day, a single plus the three home runs, and his six RBIs, the Braves lost to the Pirates 11-7.10

ROOKIE OF THE YEAR (1993)

This comedy involves a 12-year-old boy, Henry Rowengartner, who, after recovering from an injury to his arm, discovers that he can now throw a baseball at an incredible speed. That leads to a stint as a major-league pitcher for the Chicago Cubs, where Henry’s throwing skills are so good that perhaps he could win Rookie of the Year honors.

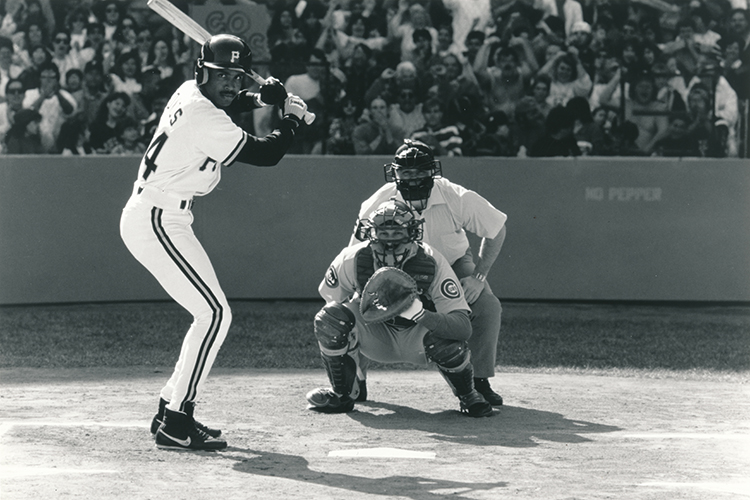

Rookie of the Year contains a nice montage sequence that shows how effective Henry’s fastball truly is. In quick succession, Bobby Bonilla, who was playing in his first season for the Mets in 1992 (the year the movie was filmed), after being an All-Star for the Pirates for many years; Pedro Guerrero, who was playing his last season of baseball for St. Louis in 1992 after a long career in the majors; and Barry Bonds, still an outfielder for the Pirates in 1992, each swing and miss one of Henry’s pitches. In particular, Bonds, in his Pirates uniform, does a nice acting job after the strikeout, seeming to marvel at how fast Henry’s pitches are. Interestingly, by the time the film was released in 1993, Bonds was playing for the San Francisco Giants, so the Pirates uniform he wore in the film was already out of date.

Barry Bonds, then an outfielder for the Pittsburgh Pirates, strikes out against 12-year-old pitching sensation Harry Rowengartner in Rookie of the Year (1993). (PUBLICITY STILL)

THE ODD COUPLE (1968)

Neil Simon’s play opened on Broadway in March 1965, with Art Carney playing neat freak Felix Ungar, and Walter Matthau playing his best friend, the slovenly sportswriter Oscar Madison. When Felix’s wife kicks him out of their home, he moves into Oscar’s New York apartment, where the entire play takes place.

In the 1968 movie version, Matthau reprises his role as Oscar and Jack Lemmon plays Felix. As was common when stage plays were adapted into films, the action was opened up somewhat for the cinema. Thus, there are scenes on the streets of New York and in a bowling alley and a diner, and because Oscar was a sportswriter, a new scene was specially written for Shea Stadium, then the home of the Mets. In that scene, Oscar is distracted by a phone call from Felix, causing Oscar to miss a triple play by the Mets.

The scene at Shea Stadium was filmed on June 27, 1967, just prior to an afternoon game between the Mets and the Pirates. Clemente was supposed to be the batter who hit into the triple play, but after thinking about the scene overnight, he turned down the part. Clemente was unhappy with the paltry sum being paid to each player, only $100, and he did not believe that his fans in Puerto Rico would understand him hitting into a triple play.11 The task was handed over to the only other Pirate who had some kind of national recognition in those days, Bill Mazeroski, the hero of the 1960 World Series. Mazeroski bats in the fake game with Pirates first baseman Donn Clendenon on first base, outfielder Matty Alou on second base, and pitcher Vernon Law on third base. Mazeroski hits a one-hopper to Yankees third baseman Ken Boyer, who steps on third and throws the ball to Jerry Buchek at second, who tosses the ball to Ed Kranepool at first for a 5-4-3, around-the-horn triple play.12

THE PRIDE OF ST. LOUIS (1952)

While much of this biography of Dizzy Dean is fanciful, the film does accurately depict an incident that occurred in the third inning of the 1937 All-Star Game. With Dean on the mound, Earl Averill of the Cleveland Indians hit a sharp line drive back at the pitcher. The ball hit Dizzy in the foot, fracturing Dizzy’s big toe. (Dizzy allegedly told the doctor that his toe was not fractured, it was broke.) Dizzy came back to pitching too soon after the accident, changing his throwing motion and hurting his arm. His famous fastball was quickly no more.13

That true incident leads to the most ludicrous scene in the film, when Dean is struggling on the mound in his first game back after suffering the injury. The opposing manager from the Pirates calls time and goes out to the mound to give Dizzy some advice about his pitching! For some reason, no one from the St. Louis team complains about the actions of the Pirates manager.

BRIEF MENTIONS

The first time the Pirates made it to the cinema was in 1906, very early in the silent era. The short film was called How the Office Boy Saw the Ball Game, a five-minute fragment of which survives to this day. In the movie, the title character deceitfully informs his boss that his grandmother has died, allowing him to leave work in order to see a New York Giants-Pittsburgh Pirates game. Watching from the top of a telephone pole outside the park through a telescope, the office boy has the opportunity to see Christy Mathewson pitching for the Giants and Honus Wagner batting for the Pirates.

In the famous conclusion to The Natural (1984), the New York Knights (a team approximating the New York Giants of the National League) is playing a team from Pittsburgh. While they have the word Knights spelled out on the front of their jerseys, the uniforms of the Pittsburgh team only have the word Pittsburgh. However, the radio announcer describing the game sometimes refers to the Pittsburgh team as the Pirates.

City Slickers (1991) involves three New Yorkers vacationing for several weeks on a cattle drive out West. One day at mealtime, two of the guys have an argument as to who is the best right fielder of their generation, Hank Aaron or Roberto Clemente. A woman in the group complains that she does not understand how men can spend so much time discussing the game and memorizing the names of the players, such as who played third base for the Pirates in 1960. The three guys respond, almost simultaneously, “Don Hoak.”

Abduction (2011) is a spy movie shot in the Pittsburgh area. The climax of the film occurs inside and just outside of PNC Park, with most of the action filmed during a Mets-Pirates game played on August 22, 2010. (Perhaps the Mets were returning a favor to the Pirates from The Odd Couple, over 40 years before.) The teenage hero of the film, Nathan Harper, wears a Clemente jersey during the action sequence, and in the final shots of the movie, Nathan spends time with his girlfriend in the seats of an empty PNC Park.

Million Dollar Arm (2014) is based on the true story of a contest to find two young athletes from India who’d never played baseball before but can be trained to become professional ballplayers within one year’s time. Just before the closing credits, the film reveals, “Rinku Singh and Dinesh Kumar Patel were both signed by the Pittsburgh Pirates 10 months after the day that they first picked up a baseball. They were the first Indian athletes to be signed by a major American sports league.”

CONCLUSION

There are other examples of the Pirates in the movies. The “Pittsburgh Team,” never specifically identified as the Pirates, appears in Hot Curves (1930) and It Happens Every Spring (1949). Characters wear a Pirates hat or jersey in Grand Canyon (1991) and The Next Three Days (2010). Along with Harmon Killebrew and Bob Feller, Mazeroski attends the funeral of a minor-league pitcher in Pastime (1990). Small-market team though it may be, the Pittsburgh Pirates have always been one of the most dominant organizations in baseball, at least when it comes to the movies.

RON BACKER is an attorney who is an avid fan of both movies and baseball. He has written five books on film, his most recent being “Baseball Goes to the Movies,” published in 2017 by Applause Theatre & Cinema Books. A long-suffering Pirates fan, Backer lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Notes

1 Warner Corbett, “Ralph Kiner,” SABR Biography Project, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/b65aaec9.

2 Pittsburgh Pirates Team History & Encyclopedia, Baseball-Reference.com, https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/PIT/.

3 David Maraniss, Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), 281-83.

4 Brooklyn Dodgers at Pittsburgh Pirates Box Score, September 17, 1947, Baseball-Reference.com, https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/PIT/PIT194709170.shtml

5 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 168-72.

6 Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentlemen (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 488-500.

7 Jack Zerby, “May 25, 1935: Ruth smashes 3 homers in final hurrah,” SABR Games Project, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/may-25-1935-ruth-smashes-3-homers-final-hurrah.

8 Robert W. Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1974), 397.

9 Creamer, 397-400.

10 Zerby, “May 25, 1935.”

11 Steve Wulf, “December 31: ¡Arriba, Roberto!” Sports Illustrated, December 28,1992, https://on.si.com/2HDSSUK; Bruce Markusen, Roberto Clemente: The Great One (New York: Sports Publishing, 2013), 166-67.

12 Barry Kremenko, “Maz Raps Into Triple Play, But It’s Only for Hollywood,” The Sporting News, July 15, 1967.

13 Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis (New York: Avon Books, 2000), 207-9