The Plot to Kill Jackie Robinson: Historian Donald Honig Plays ‘What if?’

This article was written by Ray Danner

This article was published in Not an Easy Tale to Tell: Jackie Robinson on the Page, Stage, and Screen (2022)

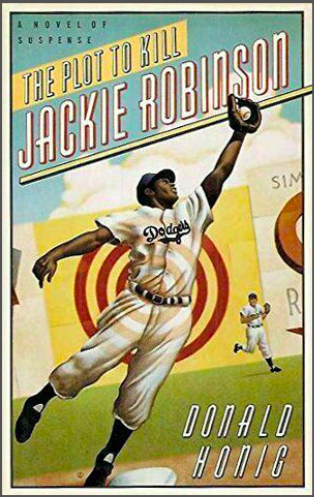

The cover of The Plot to Kill Jackie Robinson, illustration by Steve Carter & jacket design by Todd Radom. (Courtesy of Penguin Random House)

Consider this quote from eminent baseball historian Donald Honig’s 1985 book Baseball America:

“For those who cared to pay attention, Robinson’s style of play should have been both threat and warning, for this was not merely an athlete expending brutal amounts of energy to win baseball games; this was a black American releasing torrents of pent-up rage and resentment against a lifetime portion of bigotry, ignorance and neglect: this was a messenger from the brooding, restless ghettos. Only Cobb had played with the same unbuckled zeal that Robinson displayed, and Cobb was psychotic.”1

In the myriad ways Jackie Robinson’s historic achievement in Brooklyn is framed, the words “threat” and “warning” aren’t typically included. Determined, maybe, or courageous. Barrier-breaking. A hero. But a threat. And a warning. To whom? Clearly Honig did not mean only the Dodgers’ National League opponents. Baseball’s longstanding conservative “traditions”? All White America?

In Honig’s 1992 foray into fiction, The Plot to Kill Jackie Robinson, Honig provides one possible answer in the form of a White man from Queens. The fictional Quentin Wilson, an easily contemptible New Yorker with serious anxiety about the furious rate of change he sees in the country he went overseas to defend during the Second World War.

With regards to Honig’s quote in Baseball America, he created a character, Wilson, who is paying attention and who thinks he uniquely recognizes Robinson’s “threat” as indeed a message from the “brooding, restless ghettos.” Wilson believes in conspiracies. Blacks are hiding from census takers in Harlem to hide their numbers, plotting to take over. What is Wilson going to do about it? How can he stop what he sees as an inevitable revolution? Well, the answer is the title of the book.

But first, before discussing Quentin’s plot, let’s stop and assess something. Donald Honig wrote fiction?

While Honig is perhaps just behind the historians and storytellers that make up a Mount Rushmore of contemporaries like John Thorn, Roger Angell, or Bill James, his writing looms large for any reading into baseball’s past. If Lawrence Ritter’s The Glory of Their Times stands as a desert island baseball book,2 then it is Honig who picked up the oral history mantle. Honig’s first work of non-fiction, 1975’s Baseball When the Grass Was Real, repeats the formula, if not exactly the magic, of Glory.

Crossing the country to meet in person with the men who populated the game 20 to 40 years earlier, Honig interviews mega-watt stars like Bob Feller, Johnny Mize, and Lefty Grove along with lesser-known role players such as Max Lanier and Elbie Fletcher. As is common in oral histories, the lesser-known players provide the real gems with a view just outside of the clubhouse media scrum.

Fletcher stands out. As Honig reveals in his 2009 memoir The Fifth Season: Tales of My Life in Baseball, Fletcher was Honig’s brother’s unlikely favorite player when they were kids. A lifetime .271 hitter on some mediocre Boston Braves and Pittsburgh teams for 12 seasons, Honig waxes poetic about the “statistical gravity” of the long season, evidenced by Fletcher’s 1941-43 stretch batting .288, .289, and .283 in successive seasons. “Did you know that from 1917 through 1919 Ty Cobb batted .383, .382, .384? He was in the same rut you were,” Honig says. “Except for that little ‘3’ in front,” Fletcher replies.3

Honig’s mid-life transition to baseball history followed a bibliography of fiction writing that included a short story featured on Alfred Hitchcock Presents (“Man With a Problem”), a hockey player questioning the violence in the game (Fury on Skates), an 1850s covered wagon journey (The Journal of One Davey Wyatt) as well as several early forays into baseball fiction. One of these hard to find, out of print stories is 1971’s Johnny Lee; the story of a young, Black minor-leaguer from Harlem facing racism in small-town Virginia.4

Before returning to his fictional roots, Honig earned the eminent in his informal title, cranking out 43 books about baseball history over the ensuing decades, according to his online bibliography.5 Baseball Between the Lines came a year after When the Grass Was Real and repeated the oral history formula for stories from the 1940s and ‘50s. With straightforward titles, Honig covered the history of managers (1977’s The Man in the Dugout: Fifteen Big League Managers Speak Their Minds), positional rankings (The Greatest First Basemen of All Time and The Greatest Pitchers of All Time, both from 1988, followed later by catchers and shortstops), and so on through the World Series, league histories, great teams, and more.

In 1992, at the age of 61, Honig returned to his fictional roots with The Plot to Kill Jackie Robinson. In this speculative historical fiction, Honig largely stays away from the man himself and takes his readers to the bars and seedy hotel rooms of Manhattan, a quiet neighborhood in Queens, amongst the sporting crowd in Havana, Cuba, and to a deserted beach on Long Island for target practice.

Honig’s surrogate is jaded Daily News sportswriter Joe Tinker, just back from the war and sliding into a role he could easily play for the rest of his life: hard-drinking womanizer rubbing elbows with athletes and celebrities at Toots Shor’s. Perhaps like Honig himself, Tinker has ambitions beyond the sports pages. Or he’s just bored with the job.

“A sportswriter. Stamped and labeled,” Honig writes of his protagonist. “Doomed forever to write about the antics of the toy department.”6 Elsewhere, Honig has Tinker say to his editor, “Writing sports can be great – it is great – if that’s what you want to do with your life. But … it’s limiting, confining.” He continues, “The drama is artificial because it’s programmed to happen. We make it happen. It occurs because we’re there. But in reality it’s banal, because it’s going to happen again tomorrow, or next week. It’s scheduled to happen.”7

But what if this ambitious sportswriter is handed something meatier to write about? Oddly, Tinker doesn’t even seem to recognize the opportunity the imminent arrival of Jackie Robinson portends. Robinson has just finished a successful minor-league season in Montreal and seems destined to crack Brooklyn’s 1947 roster. Tinker knows that Branch Rickey plans to install Robinson in Brooklyn the following season and isn’t shy about saying so. For most of the novel, he sees this mainly as a baseball story. How will Jackie transition to first base on a loaded Brooklyn roster.

Instead, it’s a November murder in the apartment across the street from his own that gets his attention. A White man is shot dead with a Black prostitute and her pimp in the room. The White man, Harry Wilson, is a cop and former high school baseball legend from Capstone, Queens. It’s an avenue for Tinker to stick his nose into investigative reporting, pursuing “background” on Harry Wilson, and ultimately crossing paths with Wilson’s brooding younger brother, Quentin.

It’s Quentin who immediately voices the main theme of the novel – resistance to change. It’s Quentin who says, “They’re out to take everything we’ve got. They’re even coming into baseball, for Christ’s sake, with that black son of a bitch the Dodgers got up in Montreal. They’ll be in our jobs, our neighborhoods, our homes. It’s changing…everything’s changing. Somebody better do something before it’s too late.”8 Honig has created a character who keenly feels Robinson’s arrival as a “threat and a warning” and is ready to do something about it.

The apprehension around change is elsewhere in the novel, if not expressed with Quentin’s vehemence. Harry Wilson’s old baseball coach laments the buses that will soon replace the trolleys in Queens. “Progress,” Tinker offers. “Changes, changes,” the coach says. “I don’t like ‘em. Leave things as they are. We’ve been managing just fine.” Regarding veteran Tinker, he suggests “You weren’t out there fighting for changes, were you? You were fighting to keep things as they were.”

Tinker, ever the realist, thinks “I was fighting the biggest change of them all – becoming dead.”9

Harry’s old teammate Cornelius Fletcher, repeats the chorus while reflecting on the milk bottle plant where he works: “Everybody’s going to be switching over to cardboard containers before you know it.” His co-workers are “worried about their jobs. The people who unload the empties, put them in washing machines. You know how it is. Something new comes in, something old goes out.”10

Even Tinker, presented by Honig as a non-judgmental, live-and-let-live man, is not immune to pondering his fate in a changing world. “Tinker turned around for a moment and surveyed his own dark bedroom. This building was what – fifty, sixty years old? Who knew what might have taken place right in this room…But all those strangers in the light and the dark of their lives had left behind not a sound, not a trace. Human transience was probably the most puzzling and disheartening of all realities; it was the mockery of all effort and all passion.”11

Resistance to change is a theme deeply explored in countless fictional narratives. Wasn’t it Woody’s fear of losing his place as Andy’s most favored toy to Buzz Lightyear that sets the plot of Toy Story in motion? The boy in The Sixth Sense may see dead people, but it’s the reluctance of the dead to accept their fate that sets up one of the great twist endings in movie history. Stepping back to baseball nonfiction, where would modern baseball be without Michael Lewis’ Moneyball and the inevitable fallout of scouts versus spreadsheets?

What takes Honig’s examination of change out of the neighborhood and into America itself is the symbol at the center of the story. This isn’t the plot to kill Jack Johnson or Jim Brown. The Plot to Kill Whitey Ford would be a story of an obsessed fan who wants his team to have a shot at beating the Yankees for once, but it says nothing larger about society itself.

It’s the symbolism of Jackie Robinson in the most myth making of American sports, in the nation’s most emblematic metropolis, that leads to an idea that stopping one man may just stop an entire people. Robinson, the man, is a symbol on par with the unsinkable Titanic, the grandest ship in the world, doomed on its maiden voyage from Southampton to New York City while steaming recklessly through a field of ice in the mid-Atlantic without adequate lifeboats. It’s the mayor opening his beaches on Amity Island to tourists to save the summer season while a killer shark swims offshore. “It’s all psychological. You yell barracuda, everybody says, ‘Huh? What?’ You yell shark, we’ve got a panic on our hands on the Fourth of July.”12

Honig’s choice of Robinson as Quentin’s target is necessary and appropriate. It’s Robinson who stands alone at the gate between the Negro Leagues and White major-league baseball. Visible over his shoulders are Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe and Larry Doby. Hank Aaron and Willie Mays. Dick Allen and Doc Gooden. Robinson’s success, we already know, means 11 of the next 14 National League MVPs will be Black men and the balance of power in baseball will switch to the National League, generally more welcoming to Black players in the late ‘40s and ‘50s.

But more importantly to Honig’s purposes, and what he has pursued in this novel that largely stays away from Robinson’s direct presence, is what Robinson’s arrival signals.

As Cornelius Fletcher states, “Well, I know a hell of a lot of people who’ll never go to Ebbets Field again… Real Dodgers fans too. People got feelings, you know.”13

Quentin Wilson laments, “It would be the old pattern, like in a neighborhood: as soon as ‘they’ began moving in, people began moving out. Only this time the neighborhood was Baseball. The big leagues…And of course the grandstands would be filled with them too. You wouldn’t be able to go to a major-league baseball game anymore. The death of baseball meant the death of summer, and people were sitting complacently and letting it happen, letting themselves be deluded, because they didn’t realize how many of them there were and that once the tide began to flow it would be unstoppable.”14

Honig may be subtle as a hammer, but Quentin lays it out. The mechanics of how he plans to stop Robinson and whether he’s successful aren’t necessary to discuss here, expect to mention that the finale of the book bears no small resemblance to Frederick Forsyth’s Day of the Jackal, notably a novel and film focused on resistance to change, in Jackal’s case the recent liberation of Algeria by French President Charles de Gaulle. The Jackal’s ingenious method of smuggling his weapon close to his target clearly inspired Honig, as did the geography of the final shootout.

So, what does one take away from a historical fiction written over 40 years after the fact where one can assume that the bad guys fail and Robinson fulfills his destiny?

For Honig, it may be another look at the power of sports writing. Near the conclusion, Tinker’s girlfriend pushes back on his continued apathy towards his profession and his writing on Robinson’s rookie season:

You’ve got a forum. A couple million people in this city read you every day. And don’t tell me that what you write is simply an account of a baseball game. A sportswriter – a good one, one who is perceptive and can write – has a hell of a lot of scope. It may be baseball games that you are writing about, but those are human beings that are out on the field. What you say about them is going to influence how people are going to feel about them and react to them. This story is just beginning and you have an obligation to see that it’s told fully and fairly.15

In his 70s, Honig said in an interview with Marty Appel, “I’m a novelist at heart – I started as a novelist and went back to it after ’94. The last baseball books I did, I felt sort of detached. My head was drifting to other subjects, to fiction.”16

In another interview, Honig said about Tinker: “I’ve made him a guy who’s a little bit jaded by sports. He’s had this horrendous experience in World War II, and it’s helped put sports in perspective for him. Frankly, he’s bored by it all.”17

In Honig’s book, Jackie Robinson barely makes an appearance but he’s the presence, the spark, that looms over the action. It’s his impending arrival that stirs bigots to action and creates an idea in Honig’s fictional stand-in that he’s writing about more than just baseball. Honig, Tinker, and baseball fans in general have Robinson to help develop “a social conscience through baseball.”18 It wouldn’t be giving away too much to say that, much like in Day of the Jackal, the assassination fails and history proceeds uninterrupted.

Jackie Robinson the character may have escaped Honig’s fictional sniper to go 0-for-3 on April 15, 1947, and Robinson the man may have played 10 Hall of Fame-caliber seasons in Brooklyn, but Robinson the symbol and myth may well live on in stories that outlast the game itself.

RAY DANNER lives in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, where he is a local real estate investor. He can also be found underwater at the Greater Cleveland Aquarium as part of the dive team. He was on the sports beat for “The Cauldron” at Cleveland State University and a contributing writer at “It’s Pronounced Lajaway”, a member of the ESPN SweetSpot Network. Ray also plays rover on a vintage baseball club, the Whiskey Island Shamrocks. A SABR member since 2012, he is a lifelong Strat-O-Matic fan and enjoys contributing to SABR’s Games Project and BioProject.

Notes

1 Donald Honig, Baseball America: The Heroes of the Game and the Times of Their Glory (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1985), 258.

2 Mike Durell, “The Glory of Reading The Glory of Their Times,” Seamheads.com, June 1, 2015, https://seamheads.com/blog/2015/06/01/the-glory-of-reading-the-glory-of-their-times.

3 Donald Honig, The Fifth Season: Tales of My Life in Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2009), 201.

4 Honig’s book Fury on Skates was published in 1974 by Four Winds Press. His The Journal of One Davey Wyatt was a 1972 book published by Franklin Watts. Johnny Lee was published by McCall Pub. Co.

5 “Bibliography,” http://donaldhonig.com/Bibliography.html.

6 Donald Honig, The Plot to Kill Jackie Robinson (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1992), 215.

7 Honig, The Plot to Kill Jackie Robinson, 104.

8 Honig, The Plot to Kill Jackie Robinson, 15.

9 Honig, The Plot to Kill Jackie Robinson, 48.

10 Honig, The Plot to Kill Jackie Robinson, 52.

11 Honig, The Plot to Kill Jackie Robinson, 117.

12 Richard D. Zanuck, David Brown, Steven Spielberg, Peter Benchley, Carl Gottlieb, John Williams, Roy Scheider, et al., Jaws (Universal City, California: Universal), 1975

13 Honig, The Plot to Kill Jackie Robinson, 54.

14 Honig, The Plot to Kill Jackie Robinson, 44.

15 Honig, The Plot to Kill Jackie Robinson, 260.

16 Marty Appel, “Sports Collectors Digest: Don Honig & David Voigt,” appelpr.com, http://www.appelpr.com/?page_id=311.

17 Jocelyn McClurg, “Baseball Writer Hits New Hot Streak,” Hartford Courant, July 11, 1993: G1.

18 McClurg, “Baseball Writer Hits New Hot Streak.”