The Quest for Dick McBride

This article was written by Peter Morris

This article was published in SABR 50 at 50

This article was originally published in SABR’s Nineteenth Century Committee Newsletter in Winter 2008.

The main purpose of the Biographical Committee of SABR is to fill in the remaining gaps in major leaguers’ vital information. But another important mission is to ensure the accuracy of the information currently listed. The need to do this was dramatically illustrated recently in the instance of nineteenth-century star Dick McBride.

The main purpose of the Biographical Committee of SABR is to fill in the remaining gaps in major leaguers’ vital information. But another important mission is to ensure the accuracy of the information currently listed. The need to do this was dramatically illustrated recently in the instance of nineteenth-century star Dick McBride.

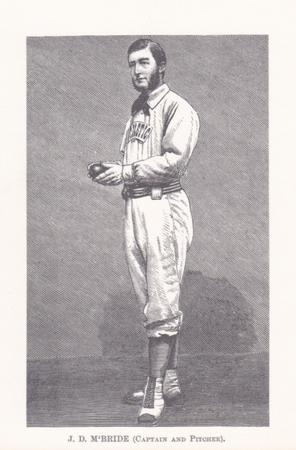

McBride was one of the greatest players of the 1860s, with his pitching skill being crucial to the emergence of the Athletics of Philadelphia as the first team outside the New York City area to contend for the national championship. Yet when Richard Malatzky, one of the top contributors to SABR’s biographical research efforts, began to determine whether McBride was a Civil War veteran, he found something amazing.

While all of the standard reference sources list McBride as dying in Philadelphia on October 10, 1916, there was in fact no evidence for that listing.

The state of Pennsylvania is notoriously difficult for this sort of research, and the absence of documentation doesn’t mean that something didn’t happen. Yet the lack of even a death notice for such a major figure was still extraordinary, and Malatzky’s research prompted a reexamination of the evidence. E-mails flew back and forth between such accomplished researchers as Civil War historian Bruce Allardice, David Lambert of the New England Historic Genealogical Society, Biographical Committee chairman Bill Carle, and Gabriel Schechter of the Hall of Fame.

It soon became clear that McBride was indeed a Civil War veteran, who served in the same company with his older brother Francis. Additional research established that his correct name was John Dickson McBride, not James Dickson McBride as had been listed. He came from a prominent Philadelphia family and worked at a clerk at the post office until 1915, at which point he disappeared from the city directories.

Pinning down his date of death remained problematic. A 1922 newspaper article was discovered that seemed to imply that McBride was still alive. Allardice found a Civil War disability pension that appeared to be dated from 1918, but unfortunately the handwriting was too poor to be certain that it wasn’t from 1908. So was McBride actually alive after his listed death date?

Going back to square one, Richard Malatzky traced the family and discovered that both of McBride’s parents were buried in Philadelphia’s Monument Cemetery. This information was passed on to Bob Bailey, a Bio Committee contributor who has an interest in ball players and cemeteries. Bob knew that Monument Cemetery no longer existed and that all of its bodies had been reinterred in Lawnview Cemetery. Having done some previous work at this cemetery, he contacted the cemetery office and was informed that a John D. McBride was buried in the family plot in Monument Cemetery on July 19, 1916, and that their records included a note that he was a baseball player.

They subsequently forwarded a copy of the original interment record, which included a newspaper clipping about McBride’s baseball career. The source of the clipping was not identified, but a hand-dated note gave the date as July 29, 1916. The article included these words: “In one of our talks last week on the numerous men in Philadelphia who have passed their three score and ten and whose lives are still full of vitality and usefulness, mention was made of John Dickson McBride, the once famous pitcher and captain of the Athletic Club in the early days of base ball. But I was in error in assuming that he was still living. I am informed that ‘Dick’ passed away on the 20th of January last and that he was buried in Monument Cemetery.”

So it appears that McBride actually died on January 20, 1916, but some questions remain. For one thing, why was there apparently a six-month gap between his death and burial? Bob Bailey notes that most cemeteries of the period had receiving vaults in which caskets were temporarily kept, and suggests that McBride’s body may have been kept there until either he was identified or until a burial site was chosen. Since he was the last family member buried in the plot, this seems plausible. A delay in identifying his body would also explain the lack of immediate mention of his death in the Philadelphia papers. (Neither the Inquirer nor the Public Ledger, the two newspapers I’ve been able to check, had any mention of his death in January.)

It thus seems that this once legendary pitcher died in obscurity and even his body may not have been identified for some time afterward. But the matter is far from closed, and research continues. The lesson of Dick McBride is therefore one that experienced researchers know all too well — that even when all the information appears to have been discovered, it is always worth checking and rechecking.