The Real Jimmie Foxx

This article was written by Bill Jenkinson

This article was published in The National Pastime: From Swampoodle to South Philly (Philadelphia, 2013)

The story of Jimmie Foxx is bittersweet. In his prime, he was one of baseball’s greatest sluggers. But his career diminished prematurely as he battled injury and alcohol. Foxx struggled with life after baseball and ultimately died before his time. So, who was James Emory Foxx, and how should he be perceived by fans in the 21st century?“You just can’t imagine how far he could hit a baseball.” Ted Williams spoke those words to me in a 1986 interview in Winter Haven, Florida. He was talking about his former friend and teammate, Jimmie Foxx. Ted’s reflection created an unforgettable image. Yet, it wasn’t what Williams said that made it so. It was how he said it…almost like a prayer whispered in a church. Teddy Ballgame was a grounded man, not given to hyperbole or casual sentimentality. But on the topic of Jimmie Foxx, he was like a child recollecting the deeds of a beloved older brother.

Later in the same conversation, Williams became teary-eyed and unashamedly emotional as he remembered Foxx, the man. Pausing to compose himself, he settled on the only words he could utter in that difficult moment: “He was a real peach of a guy.” Of course, the story of Jimmie Foxx is bittersweet, and that was on Ted’s mind as he spoke. He was there when Jimmie was still in his prime as one of baseball’s greatest sluggers. He was there when Foxx’s career diminished prematurely as he battled injury and alcohol. And Williams was well aware of how Jimmie Foxx struggled with life after baseball, and ultimately died before his time. So, who was James Emory Foxx, and how should he be perceived by fans in the twenty-first century?

Later in the same conversation, Williams became teary-eyed and unashamedly emotional as he remembered Foxx, the man. Pausing to compose himself, he settled on the only words he could utter in that difficult moment: “He was a real peach of a guy.” Of course, the story of Jimmie Foxx is bittersweet, and that was on Ted’s mind as he spoke. He was there when Jimmie was still in his prime as one of baseball’s greatest sluggers. He was there when Foxx’s career diminished prematurely as he battled injury and alcohol. And Williams was well aware of how Jimmie Foxx struggled with life after baseball, and ultimately died before his time. So, who was James Emory Foxx, and how should he be perceived by fans in the twenty-first century?

It began in 1907, when Jimmie was born in the rural setting of Maryland’s Eastern Shore. It is a place which remains today much as it was then: rolling farmlands where folks live a simpler, unadorned way of life. By 1924, at age 16, Foxx’s combination of good genes, strenuous farm work, and rigorous athletic competition had created a physical prodigy. Playing minor league ball that same year for iconic fellow Maryland native Frank “Home Run” Baker, Foxx’s Herculean abilities were quickly recognized. Before that first professional season ended, Jimmie signed with the Philadelphia Athletics to begin life as a major leaguer. And, although he traveled far while earning fame and fortune over the next two decades, his persona never really changed.

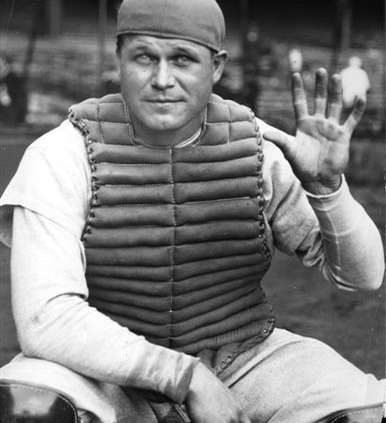

Foxx started as a catcher, but his legendary manager, Connie Mack, acquired Mickey Cochrane the same year. Mickey was four-and-a half years older and more experienced than Jimmie, so “Black Mike” had the inside track on that position. Cochrane proved his worth behind the plate, ultimately earning his place in Cooperstown. Yet, this initial change, combined with Foxx’s athletic virtuosity, caused young Jimmie to become somewhat of a defensive gypsy, moving from position to position throughout his career.

In his first few seasons, Jimmie Foxx mostly sat on the bench beside Mack, who, recognizing his potential as well as his vulnerability, groomed him cautiously. In 1928, believing his gifted protégé was ready, Mack allowed Foxx to play in 118 games (mostly at third base) for the fast-rising Athletics. In 1929, Connie turned him loose and Jimmie Foxx, age 21, became a star first baseman.

He was built like a Greek god with bulging biceps and sculpted physique. His rounded face was marked by handsome features set off by a full head of brown hair and bright blue eyes. His joy was infectious, hustling on the field with a spontaneous smile and boundless enthusiasm. He played the game with a combination of speed and power that a later generation would see in Mickey Mantle. Foxx ran like a cheetah, threw like an Olympic javelin champion, and hit the ball like Babe Ruth.

During the season in those early years, Jimmie often boarded with his Aunt Virginia, who lived in North Philadelphia, not far from Shibe Park. On other occasions, he rented rooms from homeowners who resided close to the ballpark. As a result, folks came to know him well. Local merchants, stadium personnel, and ordinary townspeople watched Jimmie Foxx grow up. They liked what they saw. Life was like a dream for young Jimmie Foxx. In 1928, when the Athletics nearly dethroned the lordly New York Yankees, led by Babe Ruth and Murderers’ Row, he teamed with future Hall of Famers Mickey Cochrane, Al Simmons, and Lefty Grove, as well as aging legends Ty Cobb, Eddie Collins, and Tris Speaker. Then, in 1929, with Jimmie pounding 33 home runs, Philadelphia actually defeated the Yanks for the American League pennant and went on to win the World Series.

In 1930 the Athletics repeated as World Champions, while Foxx slammed 37 home runs. The following year, the A’s barely missed their third straight championship when the St. Louis Cardinals prevailed in a hard-fought, seven-game fall classic. Jimmie added 30 more circuit shots that year, despite two serious leg injuries. Although the Yankees reclaimed the AL pennant in 1932, the personal ascendancy of Jimmie Foxx became complete. He batted .364, slugged .749, drove in 169 runs, scored 151 times, and slammed 58 homers to challenge Ruth’s so-called “unbreakable” season record of 60. As a result, Jimmie earned the American League’s Most Valuable Player Award.

Sadly, finances intervened, and the glory days of the Philadelphia Athletics came to an abrupt end. Largely due to Pennsylvania’s so-called “blue laws,” which prohibited Connie Mack from scheduling profitable Sabbath baseball in Philadelphia until 1934, he was forced to sell his best players. Al Simmons went first, sold to the Chicago White Sox immediately after the 1932 season. Lefty Grove and Mickey Cochrane followed after the 1933 campaign, respectively joining the Boston Red Sox and Detroit Tigers.

In the interim, despite the dwindling fortunes of his team, Jimmie Foxx enhanced his individual legacy. In 1933 he won the American League Triple Crown by recording a .356 batting average, along with 48 homers and 163 runs batted in. Jimmie also added his second straight Most Valuable Player Award. Even as the Athletics plummeted in the standings during 1934–35, Foxx kept pounding away. In those two otherwise gloomy seasons, he added 80 more home runs, batted a combined .340, and drove in 245 runs.

Yet, seemingly unknown at that moment, a malady of body and mind was growing inside Jimmie Foxx. The affliction would not destroy Foxx quickly. It would gradually erode his gifts to the point where he would never attain the supremacy for which he seemed to be destined. On October 8, 1934, while barnstorming in Winnipeg, Canada, Jimmie was struck violently on the left side of his head by a pitched ball. Batting helmets were not worn at that time. Although x-rays were negative, Foxx was diagnosed with a concussion.

He stayed in the local hospital for four days, but two days after leaving was too lethargic to play in an exhibition game in Spokane. Although this should have raised a red flag, Foxx resumed a prearranged tour to the Far East with other American League stars and sailed across the Pacific Ocean. There he played in every one of his team’s international games, including 18 in Japan. Upon returning to Philadelphia on January 6, 1935, Jimmie confirmed that he would resume the grueling duties of catcher, a position that he had not manned in seven years.

But on January 24, before leaving for spring training in Florida, Foxx underwent a double surgical procedure in Philadelphia. Dr. Herb Goddard removed Jimmie’s tonsils, along with a nasal obstruction. Hardly anyone took notice of that event, but it was a harbinger of the eventual downfall of Jimmie Foxx. The effects of his “beaning” a few months before in Canada were beginning to manifest.

As promised, Jimmie played catcher in every spring game, as Connie Mack saluted him as the best receiver in the American League. He stayed there until third baseman Pinky Higgins was injured, whereupon Foxx, the dutiful soldier, temporarily replaced him. He moved back to catcher before finally resuming his normal spot at first base on May 25. Through this period, Foxx and his teammates rarely enjoyed a scheduled off day, playing in-season exhibition games in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, Buffalo, Allentown, Pennsylvania, Bridgeton, New Jersey, and Hartford. When the season ended, Jimmie joined another troupe of barnstormers for an extended schedule of games in Mexico. These events directly preceded his sale (officially called a release) to Boston.

Coming from nearby Maryland and growing up on the A’s roster, Jimmie was viewed as a hometown hero. After he married, Foxx purchased a home in the Philadelphia suburbs, further endearing him to the local populace. Connie Mack understood this, and desperately wanted to keep “Double X” as an Athletic. Foxx played like a superstar, and wanted to be paid like one, but Mack was on the brink of bankruptcy in those hard Depression times, and was powerless to keep him. The last star level player to leave, 28-year old Jimmie Foxx departed Philadelphia for the Boston Red Sox in 1936.

In truth, Foxx was elated with the opportunity to again play for a contender while earning an income commensurate with his skills. However, he immediately acknowledged how much he would miss the Philadelphia fans with whom he had grown into manhood. For their part, Philly fans were devastated. They feared that they would never again see such a talented player in an Athletics uniform, and they never did. Predictably, Jimmie Foxx became immensely popular in Boston.

When Jimmie returned to Shibe Park for the first time as a visiting player on April 19, 1936, he was greeted in typical Philadelphia fashion. He was wildly cheered on his first at-bat, but booed thereafter by some in attendance. Even then, that was a Philly tradition. But, in their hearts, the local fans would always have a special place for Jimmie Foxx. They demonstrated that on another visit to town later that same season.

In a custom typical of the times but unknown in the modern era, the Athletics scheduled pre-game field events on September 19, 1936, when the Red Sox returned to Philadelphia. The big attraction was a 75-yard sprint race by the fastest players from both squads. It featured the A’s Lou Finney and Wally Moses against Boston’s Foxx. Although Jimmie had been a Maryland state sprint champion in high school, by that time in his career, he was primarily viewed as a burly slugger. Moses was regarded as the fastest man in the American League (along with Ben Chapman) with Finney rated right behind them. Yet, when the race ended, there was a virtual dead heat between the three; all were timed at 7.75 seconds. After some deliberation, Finney was declared the winner although the Boston Herald insisted that Foxx had finished in front.

Despite his still blazing speed, fielding virtuosity, and titanic home runs, Jimmie Foxx was showing signs of physicality that were not so benign. Earlier in the month, Jimmie had complained about vision problems associated with a sinus condition. Since he was playing productively, little attention was given to the matter.

However, when Foxx suffered through a long bout with the flu during spring training the following year, he slowly became aware that something was amiss. The Red Sox were scheduled to open the 1937 season in Philadelphia on April 20. Still not feeling well, Foxx decided to see his personal physician a few days before that opener. Again suffering from vision issues and pain above both eyes, Jimmie was quickly admitted to Jewish Hospital, where he stayed for over a week. Despite the severity of the ailment, no long-term solutions were offered. There was no apparent linkage between Foxx’s 1934 head trauma and his development of these alarming symptoms.

Consistent with the behavioral norms of his era, Jimmie Foxx rarely said anything about his almost constant battle against chronic, so-called sinus pain. But in 1939, Ted Williams joined the Red Sox, and immediately bonded with Foxx. The two men talked about their rare but mutual gift for power-hitting along with many other topics. So, when Jimmie sidetracked to Philadelphia for further treatment of his problem during a trip from Chicago to Washington on May 12, 1939, Williams knew all about it. For the record, Foxx was administered the new “radio beam treatment” without any apparent results. Within a few days of returning to Boston, he suffered a relapse. That prompted Boston team physician James Conway to assert that Foxx should have been in the hospital back in 1937 instead of playing baseball.

Later that season, Jimmie succumbed to the constant pain in his lower abdomen, and checked himself into St. Joseph’s Hospital in Philadelphia on September 9, where an emergency appendectomy was performed. When questioned by his surgeon prior to the operation, Foxx admitted that he had experienced symptoms for the past one-and-a-half-years! He finally sought treatment only when the pain became unbearable. This cost Jimmie the remainder of the 1939 season.

That incident, although not directly related to the main issue of Foxx’s “sinuses,” is an indicator of how Jimmie Foxx approached his health care. First, he never complained. Despite high levels of pain, Jimmie would simply march on, doing his best despite his burdens. Second, there was a clear pattern of postponing treatment until he could see his familiar caregivers in his former home base of Philadelphia. Many folks have that tendency, but Foxx went to extremes. Boston boasted some of the best hospitals in the country, yet Jimmie followed his country-boy instincts, and insisted on being treated only by those he knew and trusted. From a medical perspective, it was reckless and ineffective.

During those years, despite his health issues, Jimmie Foxx was still one of America’s most successful athletes. From 1936 through 1940, his first five seasons with the Red Sox, Jimmie averaged about 40 home runs per year. In 1938, when he won his third American League MVP Award, Foxx slugged 50 homers, batted .349, and drove in 175 runs (still a franchise record). But in 1941, at only age 33, Jimmie Foxx suddenly fell off the athletic cliff. Ted Williams was one of the few people who understood what was really happening.

In May of that year, Jimmie had again sought treatment for his recurring blurred vision and facial pain. This time, he was told to quit smoking, which he did. Yet there was no relief. Williams remembered those times well, and recounted some of the details in that 1986 interview. Foxx himself had been wondering if the whole pattern had begun as a result of his 1934 beaning. Prior to that time, he had no such issues.

Ted remembered Jimmie being only a “social drinker” when he (Williams) joined the Sox in 1939. He actually believed that Foxx did some of his partying because of his desire to emulate Babe Ruth. Yet, Ted did not recall any overt drunkenness on the part of Double X. Then, as Jimmie’s pain increased, so did his drinking. Williams recalled a cross-country airplane flight at the conclusion of the ’41 season when the altitude exacerbated Jimmie’s condition. As a remedy for the pain, Foxx gulped down “about a dozen” miniature bottles of scotch.

It didn’t help that Jimmie had unwisely invested in St. Petersburg’s declining Jungle Club Golf Club in late 1939. Florida’s Gulf Coast was experiencing a downward real estate spiral at the time, and Foxx had been duped into the ill-advised venture. Since Foxx loved playing golf in Florida, he had been an easy mark for business sharks trying to unload unprofitable properties. When the market failed to rebound, Jimmie’s life savings were lost. According to Williams, all this converged on Foxx at about the same time, causing Jimmie to turn more frequently to the bottle.

When Jimmie belted his 500th career home run at the implausible age of only 32 on September 24, 1940, many observers, including Ted Williams, assumed that he would ultimately surpass Ruth’s record total of 714. The next day, Williams was quoted in the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin as saying: “What a man. And I’ll bet he does it, too!” Just two months before, on July 14, Foxx had badly sprained his left knee in a collision at first base, and did not return to full duty for five days. When he did, Jimmie volunteered to catch in order to help his team. Think about that: Foxx was an established super-star slugger with 15 years of major league seniority, returning to the lineup after a serious knee injury. And he came back as a volunteer catcher, staying there for nearly six weeks!

Within days, Sox manager Joe Cronin hailed Jimmie as the finest catcher in the American League, while adding accolades about his diverse skills. In the Boston Evening Traveler on August 2, 1940, Cronin was quoted: “He’s a marvel, isn’t he? Tell me: who was a better all-around ball player than Foxxie? Why right now I’d say he was the best catcher in the American League…They can talk all they want to about some of those old time ball players being able to play different positions. I’ll take Foxxie. They don’t come any better.”

Accordingly, two future Hall of Fame legends (Cronin and Connie Mack) had labeled Foxx as the league’s best catcher, though he played that demanding position only part time. Cronin’s sentiments should not be dismissed as those of a manager hyping one of his own players. Back in 1933, when they were still adversaries, Joe had referred to Foxx as “the greatest all-around ball player in the game today.” That quote appeared in the Philadelphia Record on October 13, 1933, with Cronin specifically citing Jimmie’s fabulous power, superior throwing arm, and defensive versatility. That was the day after Foxx was voted AL MVP, just ahead of the second-place Joe Cronin. Jimmie has historically been regarded as an indifferent defender, but facts say otherwise. Surely, the testimony of Cronin and Mack means something.

On August 2, 1940, the Washington Times-Herald featured even more laudatory sentiments from writer Frank “Buck” O’Neill. He opined: “Some of these days when baseball historians meet to award the capital prize of the national game to its greatest player of all time, they are not going to give the title and plaque to Tyrus Raymond Cobb, nor to George Herman Ruth… The present day has its candidate for the greatest of all ballplayers, and his name is James Emory Foxx of the Boston Red Sox.”

Jimmie was a victim of his superb athleticism, and was often obligated to change positions. As a result, he never acquired much standing in any particular spot. Williams watched all this unfold, and never forgot Foxx’s team spirit and stalwart tenacity. It is no wonder that, in 1940, Ted thought that Jimmie would go on forever. But, almost a half-century after the fact, Teddy Ballgame felt that he knew why it didn’t work out that way. The combination of physical pain along with family and financial pressure eventually became too much for Foxx to endure. Adding to his already toxic situation, Jimmie’s wife had refused to move to Boston when he was traded there, staying in Philadelphia with their young son.

Jimmie Foxx hit only 19 home runs in 1941, and the Red Sox management hoped it was simply an off year. But when he struggled early in the 1942 season, they shipped him off to the Chicago Cubs, where his play did not improve. The disillusioned Foxx sat out the entire 1943 season, but returned to play part time in 1944 and 1945 when World War II depleted the major league talent pool. As late as 1944 Cubs manager Charlie Grimm acknowledged that Jimmie still possessed awesome power, but couldn’t hit because he could no longer see the ball. Then, playing big league baseball for the final time with the Phillies in 1945, there were even more flashes of Foxx’s once formidable athleticism.

On August 19 he was the starting pitcher for the Phils. Featuring a fastball and twisting screwball, Jimmie went six and two thirds strong innings, striking out five while recording the win. Three weeks later at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, Foxx blasted his final two major league homers by launching a pair of 420-footers into Schenley Park. When it was all over, Jimmie Foxx had accumulated 534 home runs, an impressive total, but far from the 714 predicted just a few years earlier.

As Ted Williams told us, however, many of those 534 were hit so far that Jimmie’s power now seems fictional. In every American League stadium of his era, as well as dozens of exhibition and barnstorming sites, the trail of Foxx’s longest drives challenges credibility. Twenty-four times he cleared the 65-foot high left field grandstand roof in Philadelphia. At Comiskey Park in Chicago, where no one else reached the towering roof more than twice (until home plate was moved forward in the 1980s), “The Beast” did it six times. In St. Louis at Sportsman’s Park, Jimmie powered seven tremendous drives over the left field bleachers. And so on. Everywhere Foxx logged more than just a few games, and in many places where he stopped only once, the man hit home runs that defied logical analysis.

How do we assess the career of Jimmie Foxx? Let’s indulge in some revisionist speculation. What if Jimmie Foxx was wearing a batting helmet when struck on the head by that pitched ball? Although nobody can say, it is not hard to make the case that Jimmie Foxx could have recorded 700 home runs along with the associated acclaim. Sure, in today’s world with even more substance abuse alternatives, he might have fallen just as far into temptation. So too with his financial hardship: We still see successful athletes lose their money. And, although Jimmie was self-absorbed on occasion, consider the counterpoints: Foxx had a proven history of honesty, likeability, perseverance, resilience, and intelligence. Given those attributes, negative outcomes seem unlikely.

Obviously, something did happen to Jimmie Foxx in 1941, which caused him to diminish rapidly as an athlete. There is no definitive medical proof that the 1934 event caused his subsequent problems. His medical records are now gone, but the available data strongly point in that direction. Interestingly, in February 1940, Boston teammate Fritz Ostermueller had suffered from the same symptoms as Foxx. In the case of “Ostie,” physicians linked his problem to a head trauma similar to the one Jimmie experienced in ’34. On May 25, 1935, while Fritz was pitching at Fenway Park, Hank Greenberg savagely lined a ball off the left side of his face. He soon recovered but, according to the Boston Globe (February 23, 1940), “At that time, it was also learned doctors told Fritz he might experience a reaction from the blow within ‘three or four years.’” So, why is it that nobody has connected the dots, and given Jimmie the same understanding?

Also, in the latter years of his career, Foxx referred to his malady as “neuralgia” instead of “sinus problems.” Jimmie wasn’t a physician, so it seems logical that he learned the term from one. Neuralgia and sinusitis are not the same. Neuralgia is a generic name for nerve pain which is often linked with trauma. Sinusitis is generally attributed to infections. What does it all mean? It is hard to know. Yet, with the advantage of well-documented hindsight, it seems likely that 26-year-old Jimmie Foxx had his nasal passages knocked violently out of alignment by the errant pitch in the autumn of 1934. As a result, he suffered a chronic infirmity from which he never recovered.

This we do know for sure: at the conclusion of the 1940 season, Jimmie Foxx was regarded as a genuine baseball hero. He was viewed as an athletic dynamo and poster boy for behavioral excellence. It is virtually impossible to find anyone who had anything bad to say about Jimmie. That includes players, coaches, managers, umpires, administrators, writers, fans, clubhouse attendants, or anyone else associated with Major League Baseball. Foxx was admired for his gentlemanly disposition, abiding generosity, work ethic, sincere camaraderie, and physical toughness. Then a combination of chronic pain and financial ruin became too much for him. Sadly, his premature decline has become his most notable legacy.

In the twenty-first century, Jimmie Foxx is often caricatured as a drunken failure. That is wrong. Jimmie drank heavily toward the end of his career, but there is no evidence that he was anything more than a moderate drinker until around 1940, when extreme adversity pushed him in the wrong direction. It is also true that life was often unkind to Foxx after his playing days, but, until near the end of his career, he was one of baseball’s greatest success stories. Jimmie always did his best, and did so with grace and charm. He should primarily be remembered for his joyful demeanor and Olympian talent.

How would we react if we turned on our televisions or computers at the end of a summer night, and watched a highlight of Double X blasting a 500-foot home run? Keep in mind that modern technology tells us that such blows are very rare phenomena: only two 500-footers have been hit by the combined rosters of all MLB teams since 2000. Then consider that Jimmie Foxx personally recorded at least ten such drives in his wondrous career. What would we do? In all probability, we would react just like Ted Williams. We would be in awe… and we would speak about Jimmie Foxx with respect and admiration.

BILL JENKINSON is the author of “The Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Home Runs,” and “Baseball’s Ultimate Power: Ranking the All-Time Greatest Distance Home Run Hitters.” He has consulted to the Baseball Hall of Fame, Major League Baseball, The Babe Ruth Museum, and ESPN.

SOURCES

Books

Kashatus, William. Connie Mack’s ’29 Triumph, (Jefferson, NC, and London: MacFarland and Company, Inc. 1999.)

Millikin, Mark R. Jimmie Foxx: The Pride of Sudlersville, (Lanham, MD, Toronto, Oxford: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. 1998.)

Newspapers

Baltimore Sun

Boston Evening Transcript

Boston Evening Traveler

Boston Globe

Boston Herald

Boston Post

Brooklyn Eagle

Chicago Daily News

Chicago Herald & Examiner

Chicago Tribune

Cincinnati Enquirer

Cleveland Plain Dealer

Cleveland Press

Detroit Free Press

Detroit News

Japan Times

Los Angeles Times

New York Daily News

New York Herald-Tribune

New York Times

New York World-Telegram

Philadelphia Daily News

Philadelphia Evening Bulletin

Philadelphia Inquirer

Philadelphia Public Ledger

Philadelphia Record

Pittsburgh Courier

Pittsburgh Press

Providence Journal

St. Louis Globe-Democrat

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

St. Petersburg Times

Washington Evening-Star

Washington Post

Washington Times-Herald

Winnipeg Free Press