The Rocky Colavito–Harvey Kuenn Trade

This article was written by Allen Pfenninger

This article was published in Road Trips: SABR Convention Journal Articles

This article was originally published in “Baseball in Cleveland,” the 1990 SABR convention journal.

What most Cleveland fans regard as the beginning of the end of the Golden Era of Indians baseball can be traced to Easter Sunday, April 17, 1960. The Indians, who had finished second to the Chicago White Sox in 1959, were playing the American League champions in an exhibition game in Memphis, Tennessee.

What most Cleveland fans regard as the beginning of the end of the Golden Era of Indians baseball can be traced to Easter Sunday, April 17, 1960. The Indians, who had finished second to the Chicago White Sox in 1959, were playing the American League champions in an exhibition game in Memphis, Tennessee.

Cleveland’s right fielder and 1959 AL homer champ Rocky Colavito homered over the left field wall in his first at-bat that day. In his next at-bat, in the fourth inning, he reached first base on a fielder’s choice and was removed from the game for a pinch runner. Upon returning to the dugout, he was informed by Indian manager Joe Gordon that he had been traded to Detroit for 1959 AL batting champion Harvey Kuenn.

Thus was launched the bombshell that immediately angered Cleveland fans, many of whom still regard the deal as the end of the glory days for the Tribe. The main players in this melodrama, from the Cleveland point of view:

FRANK LANE, aka “Trader Lane” and “Frantic Frank,” Cleveland General Manager. Had been a general manager with the Cardinals and White Sox before replacing Hank Greenberg in Cleveland after the 1957 season. Trades were his first love, and his claim to fame was that every team he had worked for improved in the succeeding years’ standings. Before Lane would leave the Indians just after the 1960 season, he was to make 95 deals. Lane was so proud of his trading ability that the 1960 Indians Sketchbook listed each of his transactions since joining the team. And Lane’s contract with the Indians contained a clause that promised him a bonus based on the team’s profitability. Attendance had been only 663,805 in 1958, but grew to 1,497,976 in 1959.

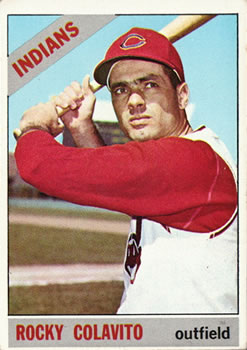

ROCCO DOMENICO “ROCKY” COLAVITO, 26-year-old right fielder. Arrived on the scene in 1955, and earned a starting role with the Indians in 1956. Known as an average hitter with good power, Colavito hit 129 home runs in his four seasons as a starter, leading the league with 42 round trippers in 1959, and his 111 RBI were just one fewer than Boston’s Jackie Jensen. Over the 1958 and ‘59 seasons, Colavito’s homer and RBI totals (83 and 224) outclassed those of both Willie Mays (63 and 200) and Mickey Mantle (73 and 172). Colavito achieved notoriety during the 1959 season by hitting four home runs in a single game at Baltimore. The handsome outfielder was a favorite with the fans and was popular with his teammates. He was rated as an average fielder, although his rifle arm was respected throughout the league (he was once a pitcher and appeared on a handful of occasions as a reliever in the majors during his career). He was regarded as a liability on the bases, and, like most power hitters, was prone to strike out. A 1959 September batting slump, during the Indian pennant drive, was an albatross that was used in part by Lane to justify the trade.

HARVEY EDWARD KUENN, 29-year-old center fielder. Kuenn arrived with the Tigers in 1952, became the team’s starting shortstop in 1953 and led the team with a .308 average. He followed that with .306 marks in 1954 and 1955. He led the league with 196 hits in 1956, batted .332 and had a career-high 88 RBI. His average dipped below .300 for the first time in 1957, to .277. His greatest year came in 1959, when he led the league in hits (198), average (.353) and doubles (42). He was rated as an excellent fielder, and had above-average speed. Through his eight seasons, he had hit only 53 home runs, with a high of 12 in 1956. The knocks on Kuenn in Detroit were that he couldn’t drive in runs and that he was injury-prone.

Before making the Colavito trade. Lane was naturally busy at work making other trades, virtually breaking up a team that had missed out on the 1959 AL flag by only five games. Two of the biggest deals were made before 1959 was even over.

Lane traded the team’s second-leading RBI man, Minnie Minoso, along with catcher Dick Brown and pitchers Don Ferrarese and Jake Striker, to the White Sox, for catcher Johnny Romano, third baseman Bubba Phillips, and unknown first baseman Norm Cash. Minoso was deemed expendable because of the emergence of Tito Francona, acquired from Detroit during the 1959 season. Ironically, Francona had a higher batting average than Kuenn in 1959 (.363) and might have won the batting title but for a lack of at-bats. Because Lane had slick-fielding Vic Power to play first, Cash was sent off to Detroit for third baseman Steve Demeter just five days before the Colavito trade.

In addition. Lane traded second baseman Billy Martin, who had failed to provide the team leadership Lane wanted in 1959, along with the 19-game winner Cal McLish and young first baseman Gordy Coleman to the Reds for second baseman Johnny Temple.

Meanwhile, Colavito proved to be difficult to sign, holding out for a contract befitting a home run champion. He eventually signed for $35,000. But, not one to let Colavito forget his shortcomings. Lane included a $ 1,000 bonus in the contract that would kick in only if Colavito hit less than 40 home runs, the idea being that Colavito was to cut down on his swing, reduce his strikeout totals and improve his average.

As the 1960 training camp convened, the Indian starting eight appeared to be set: Power, 1B; Temple, 2B; Woodie Held, SS; Phillips, 3B; Colavito, RF; Piersall, CF; Tito Francona, LF. But the emergence of a rookie outfielder from Class A, Walter Bond, turned the heads of both Lane and manager Joe Gordon. Invited to camp because of an off-season injury to backup outfielder Chuck Tanner, Bond batted .400 for the spring, with five home runs, and led the team in RBI. Despite his lack of experience, both Lane and Gordon were convinced that Bond was the real thing. Even The Sporting News picked Bond as the AL’s top rookie prospect as the season was about to begin.

This set the Lane trading machine back into motion. He had been talking about the possibility of Colavito-for-Kuenn with Detroit general manager Bill DeWitt since February, when both players were holding out Before swinging the deal. Lane met with Gordon and the Cleveland coaching staff, none of whom were against the move. Bond would provide the power, along with Woodie Held, and play right field; Kuenn would be the table-setter and play center field.

When the trade was announced in Cleveland, all hell broke loose. The team was returning to Cleveland following the Easter Sunday exhibition game for its Tuesday home opener—ironically, against the Tigers. A crowd of 300 met the team at the airport to show support for Colavito, who checked out of his Cleveland hotel and moved to another to meet his new Tiger teammates.

Lane defended the deal by citing Colavito’s September slump, saying that it had cost the team the pennant. He also was quoted as saying that the home run was overrated, citing the fact that Washington had led the league in home runs in 1959 but finished last (in fact, Cleveland had led the league in home runs with 167; Washington was second with 163). He summed it up by saying that the team had a better chance to win the pennant with Kuenn. He calculated that the team had given up 40 home runs for 40 doubles, added 50 singles and eliminated 50 strikeouts. Gordon echoed his support, adding that Kuenn was an all-around player.

Cleveland Plain Dealer sports editor Gordon Cobbledick weighed the pros and cons of each player and asked that the fans reserve judgment, while allowing for the fact that Colavito was probably one of the most popular players in team history. He concluded that “Kuenn may take the Rock’s place in the lineup and fill it with distinction, but he cannot ever take the Rock’s place in the hearts of the people—particularly the young people, who will be tomorrow’s cash customers. If the team wins, the fans will applaud. But they’ll be slow to forgive Lane for trading the Rock.”

Reaction in Detroit was not nearly as negative. One newspaper headline summarized the trade in this way: “140 singles for 42 home runs.”

On the Monday between the trade and the Opener, Lane made another deal, sending Colavito’s best friend and roommate Herb Score to the White Sox for pitcher Barry Latman. With this trade, only two players—Russ Nixon and George Strickland—remained from the team that started the 1958 season, and Lane had actually traded Nixon to the Red Sox earlier in spring training in a deal that was cancelled by the Commissioner because catcher Sammy White chose to retire rather than report to the Indians.

Opening Day in Cleveland saw a crowd of 52,756 turn out, most of them to cheer for Colavito. Many fans carried banners supporting the Rock, while others hung Lane in effigy outside the stadium. Others simply boycotted the game in protest. Colavito went hitless in six at-bats, including four strikeouts—Lane later bought pitchers Gary Bell and Jim Grant a new hat for each strikeout they recorded against Colavito. True to his reputation for injury, Kuenn pulled a muscle legging out a base hit in the extra-inning affair eventually won by Detroit, 4-2. Colavito got his revenge the next day, slugging a three-run home run, Detroit winning again.

Trades, of course, are measured over time, but the notoriety of this one led fans to compare the players throughout the season. It certainly appeared as though Cleveland had the early edge as Kuenn led the team in hitting throughout the early going, keeping his average at or near .300, with the expected low power and RBI output Colavito suffered through a slow start and slumped throughout June. The Sporting News gave the edge to Cleveland in a July 6 article, running a chart showing Kuenn leading Colavito in eight offensive statistics—notably in average (.314 to .226), hits (70 to 44) and even RBI (31 to 26). Colavito led in only one significant category—home runs (11 to 4), and had 32 strikeouts to Kuenn’s six.

The Indians were in contention, shuffling between the league’s top three spots, while the Tigers foundered in the middle of the pack, struggling to reach .500. Frank Lane looked like a genius. But was he? Walter Bond had mysteriously shown that he could not hit big league pitching and was back on the bench by the end of May with a .217 average and just three home runs. By mid-season, he was back in the minors, spending the majority of the year at Vancouver. He was replaced by Jimmy Piersall, no power hitter himself. And Woodie Held, the team’s “other” power hitter, went down for six weeks with a broken finger. An unnamed American League pitcher was quoted July 27 in The Sporting News:

“Nobody in the Cleveland lineup scares you. The Yankees and White Sox have home run hitters, and one pitch can kill you. Cleveland has a bunch of singles hitters.”

Worse for Lane (and his pocketbook), attendance was off despite the team’s remaining in contention, and Colavito came out of his slump in July, registering a .256 average with 19 home runs and 50 RBI through the end of the month.

In the second week of August, Lane and his Detroit cousin DeWitt pulled a trade just as notorious as their outfielder swap by trading managers—Joe Gordon went to the Tigers, Jimmy Dykes to the Indians. At the time of the trade, Cleveland was in fourth place, seven games out, while Detroit was in sixth, twelve and a half games out Gordon was reunited with his outfielder that struck out too much, and Lane, asked if he would still make the trade of outfielders, said, “No comment.”

Kuenn continued to contend for the American League batting crown until he suffered a hand injury in early September and broke his foot after being hit by a foul tip in mid-September, finishing him for the season. He ended the year with a .308 average, but with just 474 at-bats, nine home runs and 54 RBI. The Indians finished fourth, 21 games behind New York. Attendance dropped dramatically, and Lane’s bonus for 1960 was substantially lower than the $35,000 he had received in 1959.

Colavito finished the year with a .249 mark, 35 home runs and 87 RBI as the Tigers finished sixth. General manager Bill DeWitt encouraged Colavito to swing for the fences by paying him the $1,000 bonus in early September. Still, the season was considered to be an “off-year” for The Rock. He came back to slug 45 home runs in 1961, leading Detroit with 140 RBI as the team finished second to New York. He hit 37 round-trippers in 1962, 22 in 1963, and was traded to Kansas City, where he hit 34 in 1964. Walter Bond, unfairly projected as the next Willie Mays, finished the 1960 season with just five home runs, 18 RBI and .221 average in 40 games. He never did play regularly for Cleveland, but shone briefly as the starting first baseman for Houston in 1965 and 1966, before dying of leukemia at age 30 in 1967.

And in Frank Lane’s final trade as General Manager of the Cleveland Indians, he sent Harvey Kuenn to the San Francisco Giants on December 3, 1960, for 30-year-old pitcher John Antonelli and 26-year-old outfielder Willie Kirkland, a promising slugger. Lane cited the fact that the team needed a) a veteran pitcher to head up its young starting staff and b) some power, plus the fact that Kuenn was injury-prone.

Kuenn went on to have a couple of productive years in San Francisco, setting the table for power hitters such as Willie Mays, Willie McCovey and Orlando Cepeda. Antonelli was a bust with Cleveland, going 0-4 before being sold to Milwaukee in midseason. Kirkland played for Cleveland through 1963; his best season was 1961, when he hit 27 home runs for 95 RBI and a .259 average.

He was traded to Baltimore before the 1964 season began for Al Smith, who was released before midseason. This left the Indians with nothing to show for the Colavito deal.

Lacking an identity, the Indians foundered in the middle of the pack through 1964, and fan support dwindled. Talk of moving the team to Seattle became a real possibility. In a final effort to spark fan interest and keep the team in Cleveland, General Manager Gabe Paul brought Rocky Colavito home in a three-way deal with the White Sox and Athletics on January 20, 1965. The price to bring Colavito home was steep—starting catcher Johnny Romano, plus the organization’s two brightest prospects, pitcher Tommy John and outfielder Tommy Agee.

The 31-year-old Colavito returned to Cleveland a hero, and responded with a 26-homer, league-leading 108 RBI season. The fans responded, and baseball was most likely saved in Cleveland as a result. Colavito had one good year left with the Tribe, but was traded again in 1967 for journeyman Jim King. He retired after the 1968 season after spending time with the White Sox, Dodgers and Yankees.

It is left to conjecture as to what the Tribe would have accomplished had Colavito never been traded. He was the last legitimate “star” produced by the Indians’ organization, and it took his return to bring attendance back to where it was in 1959. His trade in 1960—and the name of Frank Lane—have been vilified in Cleveland baseball lore ever since.