The Science of Second Guessing: The Cases of Stengel, Mauch, and McNamara

This article was written by Scott Schaffer

This article was published in 2004 Baseball Research Journal

New York Giants owner Andrew Freedman fired 13 managers between 1895 and 1902. He wasn’t the first to second-guess the actions of a manager, though he did help establish a time-honored tradition. In the years since, more than a few reputations and careers have suffered the ill-effects of the practice.

Fans, owners, and journalists rightly reserve the right to scrutinize managerial decisions. With that right, however, comes a responsibility for fairness and accuracy in drawing conclusions. This article outlines a systematic approach to second-guessing managerial decisions, and applies it to three controversial historical cases, centering on decisions made by managers Casey Stengel, Gene Mauch and John McNamara. The review illuminates discrepancies between popular accounts and the real impacts of the managers’ actions.

The process consists of four steps:

1. Assessment of the Context

What information did the manager have at the time of the decision and what were his objectives at that time?

The process of second-guessing often misfires at this stage, projecting knowledge of an eventual outcome backward through time into the mind of a manager. Accurate assessment of the context of a decision is fundamental to unbiased analysis.

2. Establishment of Alternatives

What were the manager’s options at that time?

Systematically laying out realistic alternatives available to the manager provides a structure for determining a decision’s soundness.

3. Estimation of Probabilities of Outcomes

What were the possible outcomes of each alternative, and what were their relative probabilities?

In most cases probabilities can be estimated based on available information, such as past performance, known expectations, or intuitive reasoning applied to less quantifiable elements of a situation. This process can shed light on a manager’s choices, focus the observer on the essence of a decision and, often, neutralize or contradict conclusions based on gut feelings.

4. Comparison of Alternate Paths

Did an alternative the manager did not pursue have a substantial likelihood of a better outcome than the path he chose?

If so, criticism is fair game. If not, including cases in which the relative outcomes are unclear or indistinguishable, censure of a manager is unjustified. The burden of proof is on the second-guesser (much as guilt must be established beyond doubt in the legal system).

While baseball is the most quantifiable of sports, it consists of much more than numbers. Intangible factors often play important roles in decision making. These factors are best introduced after all quantifiable elements are assessed. Intangibles may reinforce the figures, contradict them, or merely fail to overrule the numbers. Applying this process to three real events, we can check how well popular assessments of managers’ decisions hold up under scrutiny.

CASEY STENGEL AND THE 1960 YANKEES

Casey Stengel managed the Yankees from 1949 through 1960, overseeing ten pennants and seven world championships. His final act with the team was Game Seven of the 1960 World Series. The favored Yankees lost 10-9 to the Pirates in the game’s last at-bat. Most explanations of New York’s shocking defeat focused on a single play: In the eighth inning, Pittsburgh’s Bill Virdon hit a would-be double-play grounder that ricocheted wildly and struck Yankee shortstop Tony Kubek in the throat, keeping a Pirate rally alive. Several managing decisions seemed worthy of controversy, but Stengel proved to be virtually immune from public criticism immediately after the Series (though the team’s ownership saw fit to relieve him of his duties just five days later).1

In subsequent years, and notably after Stengel’s death, dissent emerged. Mickey Mantle and others suggested that it was not the Kubek grounder but rather the Yankee manager who lost the Series—by failing to start Whitey Ford in Game One. Ford was one of the premier pitchers of his day (as well as Mantle’s close friend), and threw complete-game shutouts in Games Three and Six. If Ford had started Game One, the argument goes, he would have been available in Game Four and Game Seven, if necessary, and the Yankees could have avoided the disastrous finale. A popular book, The Mad Dog 100: The Greatest Sports Arguments of All Time, by Christopher Russo with Allen St. John, repeats this contention, calling the failure to start Ford three times “mind-boggling.” Applying the four-step process, we can test the validity of this case against Casey:

First, we need to assess the context of the decision. Game One was to be played in Pittsburgh. The Pirates were a mixture of talented young players and salvaged veterans with negligible post-season experience. Published odds on the Series were 7-5 in favor of the Yankees, who had won their last 15 games and were comfortable under the World Series spotlight. The Yankees were 1-4 in first games of the past five World Series they had ultimately won; Game One had not been crucial to the team’s past success.

Stengel had two valid options for a Game One starting pitcher. Alternative (a) was Ford, who had compiled 133 victories, a .693 winning percentage, and six All-Star appearances in nine seasons with New York. He had a 5-4 record and a 2.81 ERA in 12 previous Series starts. All five of those wins had come in Yankee Stadium. Ford spent time on the disabled list with a sore shoulder earlier in the year and, with just 12 victories, 1960 was among his poorer seasons. Ford was a left hander, and the Pirates’ leading batter and top three power hitters batted right.2

Alternative (b) was Art Ditmar, a right hander with 70 victories and a .511 winning percentage in seven seasons with the Yankees and Athletics. Despite a modest past, he led Yankees starters in victories, innings pitched, and ERA in 1960. Ditmar had appeared in three past World Series games, all in relief, and had a perfect ERA. Stengel credited him with staying low in the strike zone and forcing ground balls, an advantage against the reputedly high ball–hitting Pirates.

Based on the facts available to Stengel, the two alternatives carried a similar probability of success in Game One. The line on that game was even with either pitcher on the mound; oddsmakers made no distinction. We might assume a 50% probability of a Game One victory, within a range of, say, 45- 55%, but since there is no basis for differential between the two pitchers, no estimation is needed.

With little to choose between the options so far, we can consider the implications of Stengel’s Game One decision later in the Series—the intangibles. Ford had greater experience and could offer more relative benefit at critical junctures, for example, when one or both teams would face the pressure of impending elimination. It’s not clear that Ford would have been available to start three times in the Series. Note that Stengel started Ford three times in the 1958 Series, with poor results; though New York prevailed, Ford did not win a game and com- plied a 4.11 ERA.3

Assuming, as Stengel apparently did, that Ford would be available to start just two games in the Series, his relative benefit was greater the deeper in the Series those two starts occurred, particularly if one of the starts came in Yankee Stadium (in Games Three, Four, or Five), where the dimensions favor left-handed batters and pitchers. Ditmar, by comparison, lacked Ford’s post-season experience and would therefore have greater relative value earlier in the Series.

On balance, this analysis tilts the advantage to alternative (a) and supports Stengel’s selection of Ditmar in Game One. As fate would have it, the Pirates knocked him out in the first inning en route to a 6-4 victory. Ford nonetheless proved the wisdom of his assigned role by posting convincing victories at key points in the Series.

While Stengel does not deserve criticism for his Game One choice, careful analysis raises flags on several later decisions—for example, starting Ditmar a second time in Game Five, and several moves in Game Seven. Ironically, the manager flew under the radar with questionable judgment that post-season, but couldn’t escape heat for a prudent decision.

GENE MAUCH AND THE 1964 PHILLIES

Few managers have faced the sustained criticism that Gene Mauch has fielded for his role in the late-season collapse of the 1964 Phillies. The team held a 62-game lead in the standings with 12 games to go, but proceeded to drop ten in a row and finished in second place, a game behind the Cardinals. Mauch’s most criticized decision is his use of starters Jim Bunning and Chris Short on two days’ rest as the season wound down. In October 1964, David Halberstam says, “The question is the obvious one: with a lead that big, why not concede a game or two and come back with a rested pitcher and end the streak.” Philadelphia Inquirer reporter Allen Lewis offered a scathing rebuke of the manager’s pitching choices as the season ended, and such censure has entered baseball folklore. Russo and St. John repeat the charges in The Mad Dog 100, chiding Mauch’s “overmanaging.”

The reality was not so simple. Mauch had reasons to feel good as his team started a home stand on September 21. Philadelphia was making plans for the World Series and bathing the team in adulation. Mauch nonetheless knew that celebration was premature. He was specifically concerned about the state of his starting pitching, which was strong at the top with all-stars Bunning and Short, but otherwise decimated by injuries. Elbow problems had sidelined Ray Culp since mid- August, and a sore arm plagued Dennis Bennett. Journeyman Art Mahaffey and struggling rookie Rick Wise, eight days past his 19th birthday, were Mauch’s only other starters. Veteran Bobby Shantz had experience as both a starter and reliever, but he hadn’t started a game in nearly three seasons, and Mauch believed his services necessary in the bullpen, which also had little depth.

With ten games in ten days, Mauch’s options were limited. He stuck with his basic four-man rotation for the first four games; Mahaffey, Short, Bennett, and Bunning lost in succession as the Phillies’ lead dwindled to three games.4 At this point Bennett was unable to throw and could be ready, at the earliest, after five days’ rest. Mauch’s alternatives for the next six games were essentially (a) Mahaffey-Short-Wise-Bunning-Mahaffey-Short, or (b) a variation that would avoid the need to use Wise, who had started just eight games in his brief career. The latter would require using at least two of Mauch’s other starters on two days’ rest, a rare practice considered risky. (Mauch had tried this with Bunning earlier in the month, with poor results.)

Ruling out the use of Mahaffey on short rest, something Mauch did not consider, there were only two possible sequences under this plan, with the sole difference being in the final game. Sequence (b1) is Short-Mahaffey-Bunning-Short-Bennett-Mahaffey; (b2) substitutes Bunning for Mahaffey at the end.

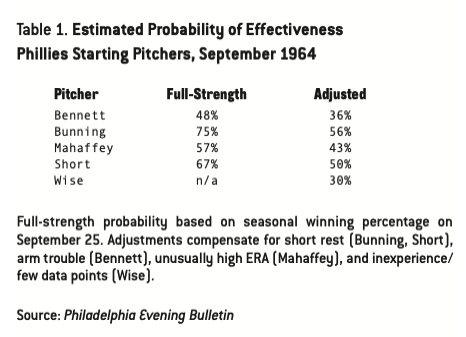

We can estimate the probabilities of success for these variations by using each pitcher’s winning percentage as a predictor of the likelihood of a victory-worthy outing, summarized in Table 1. Given the small number of data points for Wise, as well as his inexperience, his value is estimated at .3. We can compute the relative values of each sequence and test different assumptions in the process.

Table 1. Estimated Probability of Effectiveness Phillies Starting Pitchers, September 1964

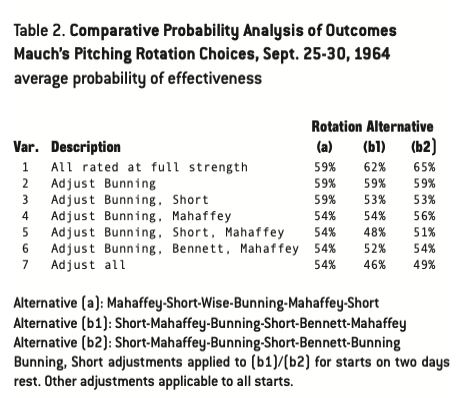

Table 2 summarizes seven different variations of probability strings for the six games, expressed as a per-game average. The first assumes that all pitchers were working at full strength, regardless of rest between starts. The second adjusts Bunning to 75% effectiveness when working on two days’ rest (based on an earlier observation), and the third does the same for both Bunning and Short.5

Table 2. Comparative Probability Analysis of Outcomes Mauch’s Pitching Rotation Choices, Sept. 25-30, 1964 average probability of effectiveness

The remaining four variations assume different combinations of adjustments, adding to the mix Mahaffey (his 4.52 ERA was a full run per game above the league average, a reflection of erratic performance) and Bennett, due to his physical problems. The figures reveal a conundrum: alternative (a), the one favored by second-guessers, is superior in three variations. But alternative (b2) is superior in two variations, and the remaining two are virtual ties. The outcome depends on the chosen assumptions, and in no case is the discrepancy greater than six percentage points.

It’s logical to assume that Bunning and Short would be less effective than usual on two days’ rest, but how critical is the 75% estimate? If the same variations are run with Bunning and Short adjusted to 88% or greater effectiveness on two days’ rest, all lean to alternative (b2). If the adjustments applied to Bunning and Short are valued at less than 67%, all variations tilt toward alternative (a). This tells us that if it was reasonable to assume at least two-thirds effectiveness for the two pitchers throwing on short rest (i.e., a probability range of, say, 67-85%), one or more scenarios justified their use in this way.

Next, we examine the intangibles. Mauch wasn’t working in an abstract statistical model in which each game was equal. After losing four straight at home, the Phillies and their fans were experiencing a crisis of confidence. Mauch felt that the next contest was critical to restoring order. His selection of his left-handed stopper, Short (2.20 ERA), over inconsistent Mahaffey had logic behind it. In addition, alternative (a) would, in the worst case, have placed Wise in front of an increasingly irritable crowd under unimaginable pressure—the final home game of the season, with a dead heat in the standings. The (b) alternatives, by contrast, had veteran Bunning on the mound that day. These facts complement the bare figures and offer support for the manager’s strategy as a reasonable one; the evidence thus justifies Mauch’s starting pitching decisions, in contrast with popular legend.

Mauch chose alternative (b2), with unhappy results in the won-lost column. For the record, however, Short actually pitched better on two days’ rest than on longer rest over the last two weeks of the season (2.84 vs. 5.50 ERA), suggesting that Mauch’s strategy may not only have been rationally conceived, but also most beneficial to his team.

JOHN MCNAMARA AND THE 1986 RED SOX

The third case is that of John McNamara, eternally associated with the demise of the 1986 Red Sox, who lost after pulling within one strike of the championship. McNamara was a lightning rod for criticism afterward, notably for failing to remove Bill Buckner late in Game Six of the World Series. Buckner’s 10th inning error that night became a fixture on highlight reels. The Mad Dog 100 ranks McNamara’s moves that year “the biggest managerial blunders in baseball history.” Let’s see if the analytic process can vindicate the embattled Boston manager or give the Mad Dog an elusive endorsement.

McNamara had multiple opportunities to remove Buckner from the game, and in fact had done so in each of Boston’s seven post-season wins that year. Buckner was a premier offensive player of his era, and a steady first baseman. Chronic ankle problems had sharply curtailed his range in the field, however, leading the manager to substitute defensive specialist Dave Stapleton when the team was ahead in late innings. The first such opportunity in Game Six came in the top of the eighth inning. The Red Sox led the Mets 3-2 and batted with the bases loaded and two outs. Left-hander Jesse Orosco was pitching for New York. Boston designated hitter Don Baylor—on the bench because the DH was not used in the National League city’s home games—was available to pinch-hit.

The manager had two alternatives at this point: (a) use right-handed Baylor to bat for left-handed Buckner, and then insert Stapleton at first base, or (b) allow Buckner to bat. Alternative (b) would allow the possibility of replacing Buckner with Stapleton at any point afterward, as well as using Baylor at a later point, if needed.

In assessing probabilities of success, we have a wealth of information, as did McNamara. Assuming that the objective for the upcoming at-bat was to get at least one insurance-run, the batter would need to safely reach base by any means. On-base percentage (OBP) is therefore the critical offensive statistic. We can combine the pitcher’s and hitters’ relative strengths in weighted OBP values, summarized in Table 3.

Baylor’s weighted OBP is much higher, .342 vs. .246, because he was more effective than Buckner against lefties, while Orosco had significantly greater success against left- handed batters. Baylor’s odds of producing a run were, by this predictor, close to 10 percentage points better than Buckner’s. Comparing the two figures directly, Baylor had a 39% greater chance of success than did Buckner in this situation. Further, Buckner had slumped badly in the post-season, with a .213 OBP, compared to Baylor’s .422.6 Orosco, for his part, was nearly perfect against lefties in recent weeks, allowing one base-runner in 18 post-season at-bats.7 These figures suggest that the actual differential between the two batters might have been larger yet.

This example shows how the analytic method can help reduce a decision to its essence and focus debate. To justify leaving Buckner in the game in this situation, McNamara had to conclude that a 10 percentage-point improvement in the chance of scoring was not worth the loss of Baylor as a potential pinch-hitter in an unknown future situation. Given that Baylor’s weighted OBP against Orosco was higher than the OBP of 25 of the 26 major league teams in 1986, while Buckner’s weighted OBP was just 80% of that of the lowest-ranked major league team, the evidence provides strong support for the pro- Baylor position. McNamara’s decision to let Buckner bat does not hold up to scrutiny.

But was his managing the worst ever? Failure to insert Baylor may have been a poor choice, but given that Buckner had 102 RBI that season, it would not seem to be of vintage caliber. Similarly, leaving Stapleton on the bench with a two- run lead in the bottom of the tenth may have been unwise, but comparison of Stapleton’s and Buckner’s career fielding percentages at first base (.993 vs. .992) would hardly have predicted the famous error.8 McNamara’s unpopular removal of Roger Clemens after seven innings of Game Six was a third controversial decision. This choice was informed by a worsen- ing blister on the pitcher’s hand, and otherwise bears close resemblance to a move another Boston manager was crucified for not making 17 years later. Upon careful review, McNamara’s detractors have not justified the degree of their vitriol.

CONCLUSIONS

These case studies demonstrate how conventional understanding of the actions of managers can be mistaken as a result of inadequate or skewed assessment of facts. Systematic analysis shows that commonly held grievances with Casey Stengel and Gene Mauch are unjustified. A specific criticism of John McNamara is validated, though the overall case against the manager has been exaggerated. On the whole, the positions of these and other managers in baseball history have been dictated more by reflexive reactions than by careful analysis.

Applied to the practice of second-guessing, the process described here can help lead to more accurate and fair evaluation of managers, stir deeper debate on baseball controversies, and help fans hold journalists to a higher standard of reporting and commentary, all of which will strengthen the game.

Sources

Boston Globe, October 26-27, 1986.

Creamer, Robert W. Stengel: His Life and Times. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996.

Evening Bulletin, Philadelphia, September 20-October 8, 1964.

Forman, Sean L., Baseball-Reference.com, 2000-2004.

Gammons, Peter. “Game 6,” Sports Illustrated, April 6, 1987.

Halberstam, David. October 1964. New York: Villard Books, 1994.

Mantle, Mickey, with Mickey Hershkowitz. All My Octobers. New York: Harper, 1994.

New York Times, October 4-15, 1960.

New York Daily News, October 4-15, 1960.

Philadelphia Inquirer, September 20-October 8, 1964.

Retrosheet, 1986 Season Players by Position, <www.retrosheet.org>, 1996-2003.

Russo, Christopher, with Allen St. John. The Mad Dog 100: The Greatest Sports Arguments of All Time, New York: Doubleday, 2003.

Sowell, Michael. One Pitch Away. New York: Macmillan, 1995.

Notes

1. Rumors of Stengel’s impending termination circulated during the Series, and concern for the popular manager’s fate may have blunted criticism of his role in the Yankees’ defeat.

2. Dick Groat won the 1960 NL batting title with a .325 average. Dick Stuart (23), Roberto Clemente (16), and Don Hoak (16) led the Bucs in homers.

3. Ford earned Game One victories in the 1961 and 1962 World Series, both of which the Yankees won. At the time of this decision, however, Stengel’s information on both Ford’s post-season performance and the correlation between Game One outcome and Series outcome were very different. Latter-day critiques seem to presume Stengel knew of Ford’s future post-season stardom in 1960.

4. Halberstam and others have misunderstood the timing of events in linking Mauch’s use of Bunning and Short to the Phillies’ collapse. The “big” lead Halberstram referred to had in fact dwindled to less than half of its September 21 level before Mauch first used Short on two days’ rest.

5. While Bunning had started once on two days’ rest, Short had not; his tolerance of this condition was unknown.

6. Baylor was a 1986 post-season hero, having saved the Red Sox’s season with a home run to help prevent elimination in the ALCS.

7. Since post-season statistics are based on a small number of data points, I consider them as intangibles, which serve to complement— and, in this case, reinforce—harder data.

8. The Red Sox had already lost their lead when the Buckner miscue occurred; even the Mad Dog acknowledges that the play is “over- rated,” hence weakening the case against McNamara for his role in the Red Sox’s demise.