The Shared National Pastime: San Diego’s First Japanese Ball Game

This article was written by Rob Fitts

This article was published in The National Pastime: Pacific Ghosts (San Diego, 2019)

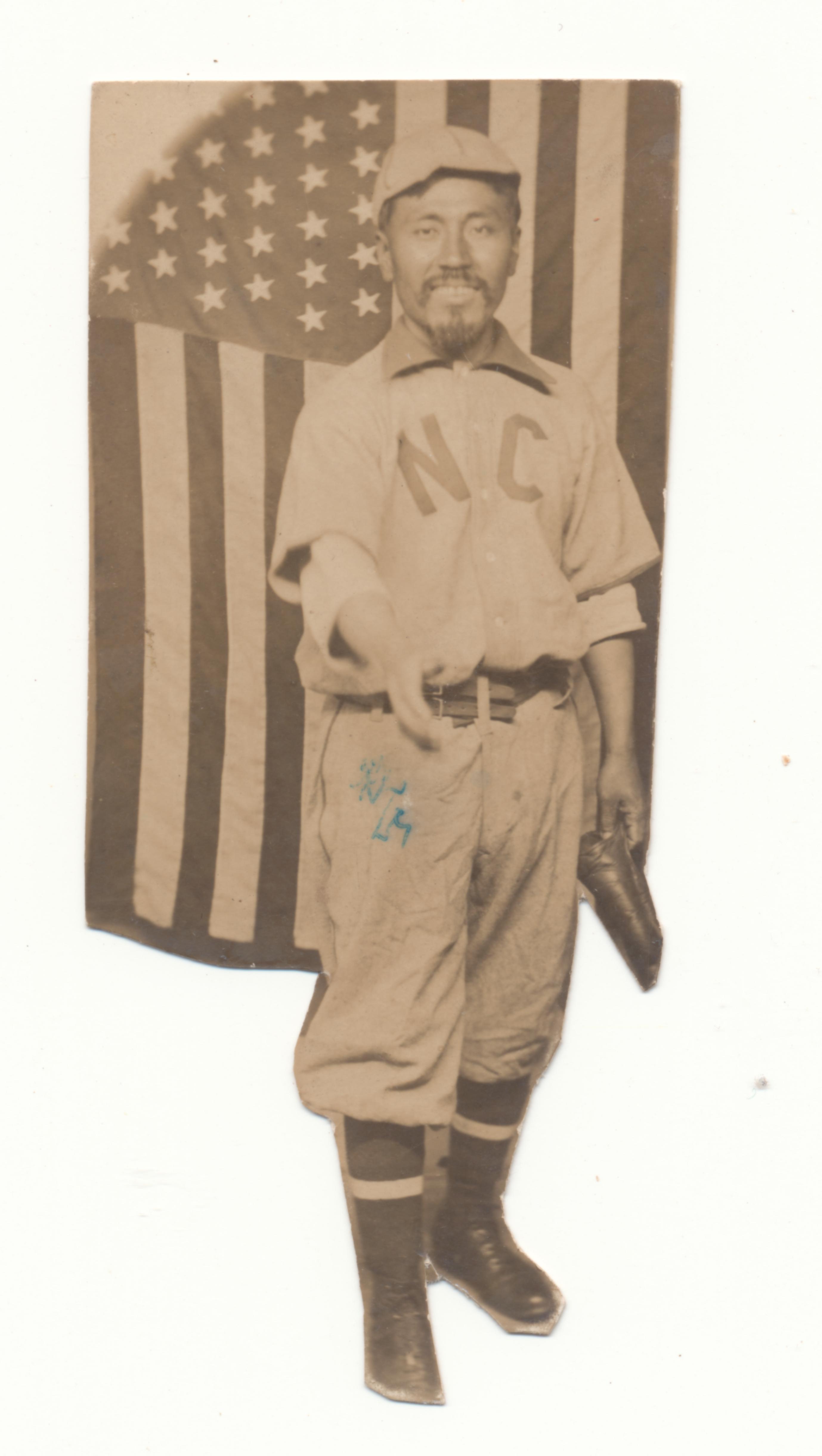

The Japanese Base Ball Association in 1911. (COURTESY OF ROB FITTS)

Since the mid-nineteenth century, baseball has helped immigrants assimilate into American society. By following their local team or taking the diamond, foreigners improve their English, become part of the cultural fabric, and learn American values. Between the mid-1890s and 1910, over 100,000 Japanese people settled in the United States. Like other immigrant groups, they struggled with bigotry and language barriers as they adapted to their new environment. But unlike other immigrants, many Japanese were already familiar with baseball. The sport would serve as a bridge between the two cultures, bringing people together with the shared love of the game.

American teachers introduced the game to Japan in the early 1870s. The sport was limited to elite schools and clubs in Tokyo and Kobe until schoolboys from Daiichi Koto Gakko (the First Higher School), commonly known by its nickname, Ichiko, upset an American adult team from the Yokohama Country Club in a series of games in 1896. After the Japanese victory, teams sprang up on high school and college campuses across the country.

Having learned the game in Japan, many Issei (Japanese immigrants) longed to continue playing. Excluded from most white American teams, they formed their own clubs. Between 1903 and 1905, Issei established the Fuji Athletic and Kanagawa Doshi Clubs in San Francisco, the Japanese Base Ball Club of Los Angeles, and Nippon Baseball Club in Seattle.1

In the spring of 1905, the Waseda University baseball club from Tokyo became the first foreign team to tour the United States. It played 26 games mostly against college and semi-pro teams in California, Oregon, and Washington. Fans packed ballparks to watch the novel team and newspapers covered the games with extensive articles. Waseda’s popularity introduced Japanese baseball to white Americans and turned many Issei into baseball fans and players.2

Inspired by the publicity surrounding the Waseda University tour, Guy Green, the owner of the barnstorming Nebraska Indians team, decided to create a barnstorming team of Japanese players. He recruited a squad of Issei from the West Coast and sent them on a 150-plus-game tour of the Midwest during the summer of 1906. They would be the first professional Japanese team on either side of the Pacific.3

Returning to Los Angeles, members of Green’s squad decided to form their own team known as the Nanka (meaning Southern California) Baseball Club under the leadership of Atsuyoshi “Harry” Saisho. The son of a samurai who had fought against Takamori Saigo during the 1877 Satsuma Rebellion (the war was the basis for the romanticized Tom Cruise movie The Last Samurai), Saisho had learned the American game while at school in Miyazaki on Japan’s southern island of Kyushu. In 1903, Saisho emigrated to California with dreams of attending Stanford University. Finding his English inadequate to enroll, he drifted between menial jobs before settling in Los Angeles.

Returning to Los Angeles, members of Green’s squad decided to form their own team known as the Nanka (meaning Southern California) Baseball Club under the leadership of Atsuyoshi “Harry” Saisho. The son of a samurai who had fought against Takamori Saigo during the 1877 Satsuma Rebellion (the war was the basis for the romanticized Tom Cruise movie The Last Samurai), Saisho had learned the American game while at school in Miyazaki on Japan’s southern island of Kyushu. In 1903, Saisho emigrated to California with dreams of attending Stanford University. Finding his English inadequate to enroll, he drifted between menial jobs before settling in Los Angeles.

The Nanka played against amateur and semipro white and black teams nearly every weekend and attracted the area’s top Japanese players. “We were crazy about baseball,” recalled infielder Kiichi Suzuki. “Nothing was more interesting than playing baseball on Sundays and holidays when we were young. We never took jobs that would prevent us from taking Sunday off, no matter how good the opportunity was.”4

In early 1909, Saisho’s team decided to turn professional and barnstorm across the U.S. as the Japanese Base Ball Association (J.B.B.A.). They began in California but after embarrassing losses to an amateur team in Riverside, the African American L.A. Giants, and Los Angeles High School, they dissolved the squad. Suzuki noted that the team was “enthusiastic but incompetent.”5

Six months later, when the African American Occidentals from Salt Lake City visited Los Angeles, Jesse Orndorff, the catcher for the Pacific Coast League’s Los Angeles Angels, organized a game between the Occidentals and the city’s top Japanese players. The Los Angeles Herald ran articles on the event for two straight weeks, noting that “the baseball game . . . is an exhibition of the national game in which race supremacy in the art will be settled.”6 Two thousand fans came out to watch. Although Saisho and some of his best players dropped out of the game at the last minute, the excitement surrounding the event prompted Saisho to reunite the J.B.B.A. and continue the club’s quest to turn professional.

In late December 1909, Saisho traveled to San Diego to arrange games for the squad. The San Diego Union reported, “Saisho says he realizes that the San Diego Midwinter league team would be too fast a proposition for his countrymen but that he would like to play any amateur or semi-professional aggregation of hit and run artists.”7

The games, however, did not materialize and Saisho later tried to schedule a game for February. This time, he intended to combine the baseball game with a wrestling match. The Union wrote:

Harry A. Saisho, the polite little Japanese who was in San Diego about two months ago is now developing into a manager of wrestlers. . . . Saisho’s English is a trifle faulty, but his intentions are good. His letter . . . is reproduced below in full:

Sporting Editor, San Diego Union:

Dear Sir: I am much obliged to you helped us as much as possible past time. I trying to get game (baseball) now in Feb. or first March if possible for we may not stay any longer than March. Here is another sporting matter. My friend Mr. R. [Ryo] Fukada, that jujitsu wrestler—he matched to Young Johnson, middleweight champion of coast and won about 9 minutes, Jan. 4th at Los Angeles. He willing to get one fight to a wrestler in San Diego in recent. He will be here in a few days. Please let me know a man attend on. He weight about 140 pounds or more. I believe he is more stronger than Yokohama called a world champion. Please notify soon possible.

Harry A. Saisho8

The letter worked and Saisho arranged both a ballgame and a match for Fukuda, a Japanese-born Harvard student, for late February.9

A week before the game, San Diego’s newspapers began running advertisements and articles on the upcoming event. A large crowd was expected as it would be “the first time the fans have ever had the chance of seeing a Japanese team of baseball players in action.” The Union reported, “The Japs are now playing a fast game of ball and should be able to give the locals a run for their money. The little brown men are said to be exceptionally fast at fielding and running bases and in previous games have demonstrated their ability to keep the man behind the bat constantly on the alert.”10

The J.B.B.A. featured some of the top Issei ballplayers in the country. Saisho’s childhood friend Ken Kitsuse played shortstop. Just under 5-foot-3 and 115 pounds with a boyish face, he was often mistaken for a child by opposing players and fans. But he could “field like a cat” and run the bases like a demon.11 Kitsuse was a natural athlete, excelling at judo, kendo, and long-distance running as well as being the best Japanese ballplayer on the West Coast. Teammate Kiichi Suzuki remembered, “We considered him the god of baseball. When somebody made a mistake, he would give him hell [or in Japanese, ‘drop thunder’]. For this reason, we called him Thunder.”12

The fleet Minoru Sohara, another of Saisho’s childhood friends, played left field. Although not much of a hitter, he could field his position well and was an expert with the sword, often entertaining fans with pregame demonstrations with his gleaming katana or wooden bokuto. Suzuki played second base. From Chiba, just east of Tokyo, Suzuki had played on the Waseda University practice team (similar to a junior varsity), learning the game from Japan’s best players. Filling out the squad was Toyo Fujita at first, a former member of Guy Green’s Japanese barnstorming team; Riichiro Shiraishi in right field; and Morii in center. Saisho would play third base.

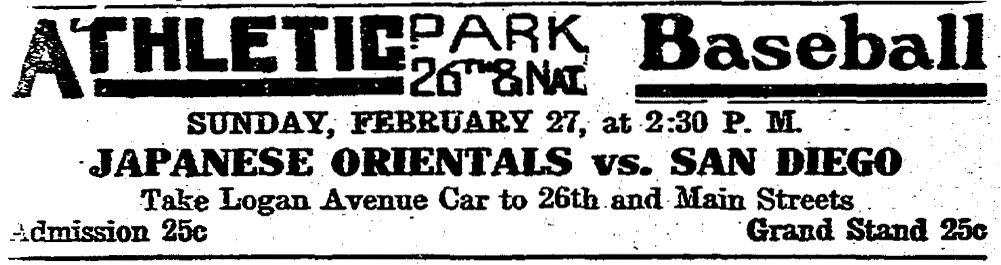

Advertisement for the San Diego game from the San Diego Union, February 27, 1910. (COURTESY OF ROB FITTS)

The J.B.B.A. would have its hands full. The San Diego squad had won the California Winter League championship for the past two seasons and would win the next two as well. The team featured at least two big-leaguers—third baseman Tom Downey, who played for the Cincinnati from 1909 to 1911, and first baseman Chick Autry, his Reds teammate. To be competitive, Saisho recruited two ringers. Orndorff of the Angels would catch while Jim Scott of the Chicago White Sox would take the mound. The 21-year-old had just finished his rookie season, going 12–12 with a 2.30 ERA. He would pitch for nine years in Chicago, winning 107 games, and accompany the White Sox on their 1913 visit to Japan.

Despite threatening rain, fans crowded into Athletic Park on Sunday, February 20, filling the covered wooden grandstand behind home plate and the bleachers down the foul lines. All were eager for the novel game. Yet game time came and went without the Japanese taking the field. Seeing the weather report in a Los Angeles newspaper, Saisho had assumed the game would be canceled and kept his team at home. A flurry of telegrams identified the misunderstanding and rescheduled the game for the following week.13

Anticipation grew during the ensuing week. The Japanese “will interest many of the fans who have read of the exploits of the mikado’s subjects in the national game,” noted the San Diego Union.14 Fans were particularly excited to see Scott pitch. To prevent another misunderstanding, San Diego manager Will H. Palmer telephoned Saisho on Thursday night confirming the game.

On Saturday, February 26, Saisho and most of the team arrived in San Diego for Fukuda’s wrestling match, to be held that evening at Arizona Hall. Prior to the main event, the ballclub’s left fielder, Minoru Soharu, challenged local fencing expert K. Suzuki in a kendo match—the first held in the city. Afterward, Fukuda faced amateur wrestling champion Tom Travers in the ring. The rules were simple. Travers could use any style of grappling he wished, but Fukuda was limited to jiujitsu holds and throws. The first to fall twice would lose. Strangely, despite extensive pre-match newspaper coverage, the result of the bout is not recorded in local papers.15

The following afternoon, fans once again packed Athletic Park to watch the Japanese play the local champions. Once again, the fans had to wait. The Santa Fe train from Los Angeles, carrying Scott, Orndorff and two Japanese players, was delayed. On the diamond, the players practiced as they waited. After an hour, Palmer and Saisho decided to entertain the fans with “a scrub game” until the missing players arrived. Palmer recruited local amateur players to fill out the Japanese team while San Diego’s John Lambert took the mound for the Japanese against his usual teammates.

The contest, however, was completely one-sided. According to the Union, Saisho’s team “at no time had a chance to win. At times the Japanese players showed their ability as fielders, but their batting was so weak that although [the San Diego pitcher] merely ‘lobbed’ the ball across the pan they were able to get but a few scratch hits.” To entertain the crowd, the San Diego team “made the game one long joke [which] provided plenty of fun for the people in the grand stand and the bleachers.” By the time the missing players arrived, “most of the spectators had left the grounds.”

At 4 p.m., Scott took the mound for the J.B.A.A. and the feature game began in front of near-empty stands. The Evening Tribune noted, “The spectators who remained were well repaid for their long wait” as Scott dominated. Using a blazing fastball and sweeping curve, he struck out eight in just four innings before the game was called on account of darkness after only an hour of play. The “exhibition would probably have been one of the best of the season, had it started on time,” lamented the newspaper.16

Although the game was a near disaster, it did not deter Saisho and his J.B.B.A. teammates from pursuing their dream to turn pro. The squad returned to Los Angeles, recruited several new players, and practiced. The next spring, they embarked on 150-game barnstorming tour of the Midwest, becoming the country’s only professional Issei team. Later, the ballplayers would form their own teams, coaching the next generation as baseball became an integral part of Japanese American culture.

ROBERT K. FITTS is the founder of SABR’s Asian Baseball Research Committee and he writes about the history of Japanese baseball and the game’s role in US-Japan relations. He has published four books on the topic including “Banzai Babe Ruth” (winner of the 2012 Seymour Award) and “Remembering Japanese Baseball” (winner of the 2005 SABR Research Award). His next book on the history of early Japanese American baseball will be published by the University of Nebraska Press in 2020.

Notes

1 Kerry Yo Nakagawa, Japanese American Baseball in California (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2014); Samuel O. Regalado, Nikkei Baseball (Urbana IL: University of Illinois Press, 2013).

2 Robert K. Fitts, “Baseball and the Yellow Peril: Waseda University’s 1905 American Tour,” in Base Ball 10, ed. Don Jensen (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2018), 141–59.

3 Fitts, “The First Japanese Professionals: Guy Green’s 1906 Japanese Base Ball Team,” Nine (forthcoming).

4 Masaru Akahori, Nanka Nihonjin Yakyushi [History of Japanese Baseball in Southern California] (Los Angeles: Town Crier, 1956), 4.

5 Akahori, Nanka Nihonjin Yakyushi, 3.

6 “Japanese vs. Negroes,” Los Angeles Herald, December 18, 1909.

7 “Japanese Baseball Team Wants Games Here Christmas Day,” San Diego Union, November 4, 1909.

8 “Jap Mat Artist Looks for Match,” San Diego Union, January 14, 1910.

9 “San Diego Wrestler Will Meet Japanese,” San Diego Union, February 19, 1910.

10 “Jap Base Ball team to Play Big Leaguers,” San Diego Evening Tribune, February 19, 1910; “Little Brown Men to Play Local Team Today,” San Diego Union, February 20, 1910.

11 “War with the Japanese is Over,” Audubon Country Journal, August 31, 1911.

12 Akahori, Nanka Nihonjin Yakyushi, 12.

13 “Jap Aggregation Fails to Appear,” San Diego Union, February 21, 1910.

14 “Will Try for Mat Honors Saturday,” San Diego Union, February 25, 1910.

15 “San Diego Wrestler Will Meet Japanese,” San Diego Union, February 19, 1910, 7.

16 “Scott Makes Hit with Fans by Speedy Work in Box,” San Diego Union, February 28, 1910; “Scott Pitches Elegant Ball in Fast Game,” San Diego Evening Tribune, February 28, 1910.