The Stallings Platoon: The 1913 Prequel

This article was written by Bryan Soderholm-Difatte

This article was published in Fall 2016 Baseball Research Journal

Johnny Evers (left) on the Braves in 1914 with his manager, George Stallings (right). As player-manager of the Cubs in 1913, Evers took himself out of the lineup against left-handers, but George Stallings (right) used handedness substitutions in the Braves’ lineup regularly for strategic advantage starting in 1913. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

The Fall 2014 issue of The Baseball Research Journal included the article, “The 1914 Stallings Platoon: Assessing Execution, Impact, and Strategic Philosophy,” in which I noted that, while “1914 is considered the baseline year for platooning” because of the compelling narrative of Boston’s “Miracle” Braves, it seemed quite likely that Braves’ manager George Stallings also platooned in his outfield the previous year—1913, his first year in charge. At the time the article was written, 1914 was the earliest year for which the starting lineups and box scores for every game of the season, compiled by Retrosheet researchers, were available on the websites Retrosheet and Baseball-Reference.com. The judgment that Stallings probably also had an outfield platoon in 1913 was based on an analysis of gross Retrosheet data on position games played by Braves players relative to the number of games started against them by left-handed pitchers.1

Now, however, thanks to the painstaking work of Retrosheet researchers, comprehensive data on the starting lineups for every game in the 1911 (NL only), 1912, and 1913 seasons are now available.2 This newly available information allows a definitive assessment that not only did Stallings in fact begin platooning in 1913, several other managers did so as well. Moreover, the 1911 and 1912 data indicate that 1913—and not any year earlier3—was the first time that platooning lefty and righty batters for a significant portion of the season depending on the handedness of the opposing starting pitcher was done on a systematic basis in the major leagues, although only by a few clubs.4

POSITION-PLAYER SUBSTITUTIONS FORESHADOW PLATOONING

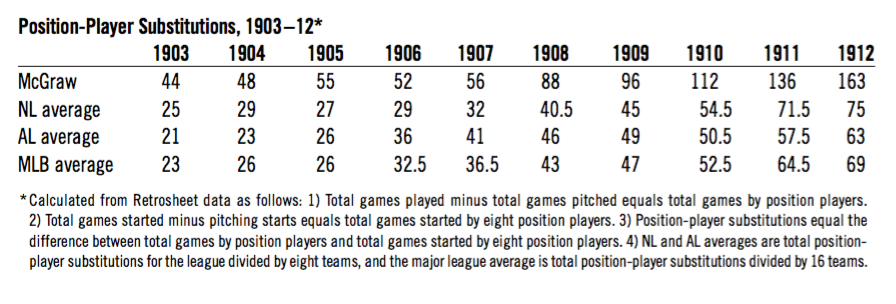

As noted in my previous article, players and managers already understood that left-handed batters had an advantage against right-handed pitchers and vice versa. John McGraw was the first manager to work that concept into a game strategy by his willingness to pinch hit even for his starting position players for the lefty-righty (or righty-lefty) advantage at critical moments of the game. Other managers followed his lead, although he employed the tactic far more often. From 1903—McGraw’s first full season managing the Giants—the number of position-player substitutions in the major leagues began to increase every year, mostly pinch-hitters or, sometimes, pinch-runners who then required a defensive replacement (see Table “Position Player Substitutions, 1903–12”).

By 1912, the number of in-game position-player substitutions over the course of a major league season tripled from an average of 23 per team in 1903 to 69 per team.5 Catchers were swapped out far more often than other position players because many were weak hitters, slow on the bases, or as a result of the taxing physical demands and injury risks they faced. Every year from 1908 to 1912, McGraw’s position-player substitutions were more than double the major league average.

Notwithstanding the value of “playing the percentages” by substituting for the alternate-side-of-the-plate advantage at a pivotal moment, the validity of platooning as a concept for determining starting lineups still remained to be seen. Theoretically, it made sense, but whether it was a practical option over the course of a long season was an open question. Managers had always assumed the importance of position-player stability in the starting lineup—seven infielders and outfielders who could be relied upon day in and day out, and a pair of catchers because of the position’s rigors and risks—and McGraw was no different. All self-respecting position players wanted to play every day, and the regulars expected to be in the lineup every day regardless of who was pitching for the other team. When there were changes in the starting lineup, they were rarely day-to-day with different players being tested out, and certainly not with respect to the day’s opposing starting pitchers; the replacement position player almost always was in the lineup for an extended period of at least weeks until the established regular was back in action after an injury, he himself was injured, or he proved not up to the job, paving the way for another player to be tried at the position.

However, as suggested in my article two years ago, platooning in starting lineups was ultimately inevitable, probably sooner than later. “An argument can be made,” I wrote then, “that platooning two players (or sometimes more, as Stallings did in 1914) at the same position to take advantage of a right-handed/left-handed split became institutionalized by the collective wisdom of managers observing and learning from each other and becoming more strategic in their thinking.” The fact that six managers platooned in 1913—the year before the “Miracle” Braves—suggests that judgment was probably correct. Rather than platooning being the brainchild of Stallings alone, it seems instead to have been a strategy whose time had come, then if not sooner. It was a logical outgrowth of the trend toward managers increasingly being willing to replace a starting position player at a critical juncture in the game, mostly to gain a batter-pitcher advantage by pinch hitting for him.

WHO STALLINGS PLATOONED IN 1913

The Boston Braves were a terrible team when George Stallings took over in 1913. They had suffered through four consecutive years not only finishing dead last in the National League, but losing 100 or more games each season. Second baseman Bill Sweeney, third baseman Art Devlin—who had mostly played out of position at first base and shortstop in 1912 for the Braves so that Ed McDonald could play third—and right fielder John Titus were the only holdovers of the regulars from the previous year in Stallings’s plans for the 1913 season.6 It is not apparent Stallings planned to platoon at any position when the season started.

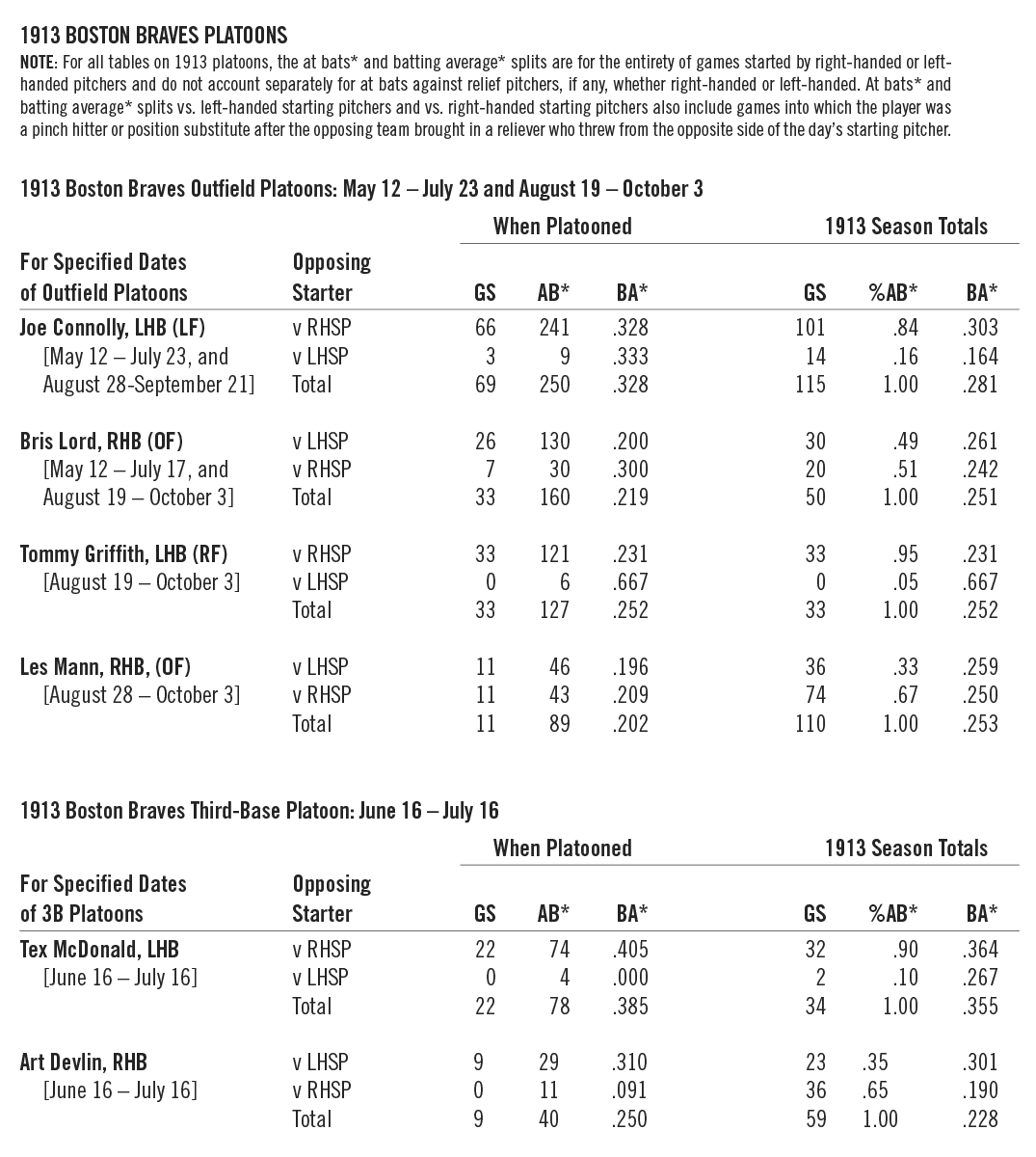

Stallings had settled on left-handed-batting rookie Joe Connolly to be his everyday left fielder, but it soon became clear that Connolly was struggling, particularly against southpaws. Starting in all but two of the Braves’ first 21 games and batting third in the lineup, Connolly’s batting average was down to .184, and his on-base average was just .253. The Braves had faced a left-handed starting pitcher in six of their first 21 games, and Connolly was in Stallings’s starting lineup in all of them. He had collected just 3 hits in his 24 at bats in those games, however, for a wholly inadequate .125 batting average. Connolly’s average against righties was not much better at .212. With the Cardinals sending lefty Slim Sallee to the mound against his team on May 12, and probably well aware that Connolly was hitless in 16 at bats the last four times the Braves had faced a left-handed starter, Stallings decided to start right-handed-batting Wilson Collins in left field instead. Beginning a pattern that would be clearly evident in the box scores that year, as well as in the Braves’ 1914 “miracle” season, Stallings brought in Connolly to finish the game in left field after Sallee was replaced by a right-handed reliever.

From then through July 22, Connolly started just three of the 17 games a southpaw took the mound against the Braves, and all 49 games when a right-hander did. He batted .344 in those 52 games— raising his batting average to .298—and hit the first five home runs of his career. When facing a lefty starter, Stallings replaced Connolly in the starting lineup with the right-handed-batting Bris Lord, a veteran in the last year of a playing career spent mostly as a reserve outfielder for the Philadelphia Athletics. Lord batted just .245 (12-for-49) in his 12 starts as the right-handed half of the left field platoon, and .198 overall in 36 games—including seven starts in right field, five of which were against right-handed starting pitchers.

A season-ending injury to John Titus on July 17, however, forced Stallings to use both Connolly and Lord every day for the next six weeks. Connolly started in five of the seven games a left-handed pitcher took the mound for the other team with 3 hits in 17 at bats (.176) in the time between Titus’s injury and August 21.7 By then the Braves had acquired another left-handed-batting outfielder of promise, Tommy Griffith, which allowed Stallings to platoon in both left and right, starting the lefty-swinging Connolly and Griffith against right-handers and the righties Lord and Les Mann against southpaws the rest of the season. Mann had been the Braves’ center fielder but was displaced by the left-handed-batting Guy Zinn when he joined the Braves about the same time as Griffith.8 In the 42 games the Braves played after August 20, Connolly did not start any in which a southpaw took the mound against his team.

All told, Connolly played 126 games in his rookie year, starting in 115 of the 140 games the Braves played before he was forced to sit out the remainder of the season because of an injury. The Braves faced off against a southpaw pitcher in 36 of those games before he got hurt, in which Connolly was in the starting lineup 14 times. He batted just .180 with 9 hits in 50 at bats in those 14 starts, which included all of the hits he collected off any right-handed relievers who might have been brought into those games.9 In the 101 games he started against right-handed pitchers, Connolly hit for a much better .303 average. Again indicative of the pattern clearly established the next season, Stallings often removed him from the game in favor of a right-handed-hitting outfielder if a left-handed reliever was brought in; Connolly was in at the end of only 100 of the 115 games he started.

For the middle part of the 1913 season, Stallings also platooned at third base. The right-handed-batting Art Devlin, returning to his familiar position, began the year as Stallings’s everyday third baseman, playing in all except four of the first 50 games, but as of June 15 he was batting just .230. His batting splits must have been revealing to Stallings—a neat .300 in the 13 games the Braves faced a southpaw starter, but only .205 when a right-hander took the mound against Boston—even if he didn’t know or have access to the specific statistical data. Stallings found such a low batting average difficult to stomach even for someone batting in the bottom third of the order, and since he happened to have sitting on his bench a left-handed-hitting infielder who could play third base named Tex McDonald, the Braves’ manager decided to see how each would fare in a platoon role.10

A part-time shortstop for Cincinnati as a rookie the previous year, McDonald had spent most of his first month in Boston on the bench after arriving in an early May trade, used almost exclusively as a pinch hitter. Given the opportunity to start eight games in the beginning of June, substituting for either Devlin at third or Bill Sweeney at second when they were nursing various aches and pains, McDonald batted .323. That was sufficiently impressive to Stallings that for the next month—June 16 to July 16—he started McDonald at third in the Braves’ 22 games against righties and Devlin in the 9 games that a southpaw started for the other team. McDonald batted a robust .405 in those games, while Devlin batted .310 in his starts. McDonald appeared in three games replacing Devlin when a lefty reliever came in, without a hit; Devlin had just one hit in 11 at bats as a position substitute for McDonald when a left-handed reliever got the call.

Notwithstanding that both McDonald and Devlin were hitting well in their platoon roles, beginning on July 17, Stallings turned to right-handed-batting Fred Smith, a rookie, to play third the rest of the way, regardless of who the starting pitcher was.11 Smith was batting just .200 in 24 games when Stallings put him into the starting lineup to stay on July 17. He went on an 11-game hitting-streak, including three 3-hit games, to end the month batting .302. Smith ended the year batting .228, including .230 in games a right-hander took the mound and .222 in the games when he had the presumed platoon advantage against a southpaw starting pitcher. After Smith became the regular third baseman, Devlin made just four more starts for the Braves—two against right-handers—before being released on August 25. McDonald started just three times at third base after July 15, once against a lefty, and did not play again after going 2-for-4 as the starting third baseman on August 28.12 For full breakdown of the 1913 Braves platoons by starting pitcher handedness, see Tables 2 and 3 below.

(Click image to enlarge.)

THE FIVE OTHER TEAMS THAT ALSO PLATOONED

George Stallings was not the first manager to try platooning in the 1913 season. In Brooklyn, manager Bill Dahlen opened the season with right-handed-batting rookie Benny Meyer in right field, but getting just two hits in his first 19 at bats, Meyer lost his job after five games. For the next seven weeks, Dahlen opted for the left-handed-batting Herbie Moran in games started by right-handers and the right-handed-batting John Hummel against southpaws. Moran was a regular in the Brooklyn outfield in 1912, his first true season in the big leagues after having played a smattering of games from 1908 to 1910, and Hummel had been with Brooklyn since 1905, playing as a day-today regular in both the outfield and infield from 1908 to 1911. The Moran-Hummel platoon ended in early June when Dahlen decided to go with Moran as his regular right fielder the rest of the year. In the 21 games he started against righties while being platooned, Moran’s batting average was .235, while Hummel batted .290 in his 14 starts when a southpaw took the mound against the Superbas (as the Dodgers were then called). For the season, during which he also started 23 games in the infield regardless of who was pitching, Hummel was a far better hitter when he had the platoon advantage, batting .327 against lefties and only .160 against righties with almost exactly the same number of at bats.

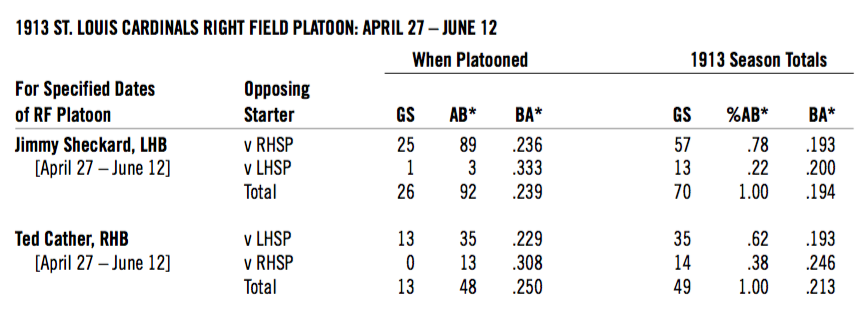

Miller Huggins, in his first year as manager of the St. Louis Cardinals and their second baseman besides, also began platooning in late April, about two weeks before Stallings decided on his left-field platoon. Twelve games into the season, Cardinals right fielder Steve Evans—a regular in their lineup since 1909—was hurt on a fielding play, and Huggins decided to alternate veteran left-handed-batting Jimmy Sheckard in right field with rookie Ted Cather, a right-handed batter, depending on whether a righty or a lefty took the mound for the other team.13 Huggins’s decision to platoon might have been influenced by his being a switch-hitter, so he personally would have known the benefits of batting from the other side of the plate from the pitcher’s throwing arm. The Cardinals’ outfield platoon ended once Evans was back in action, perhaps because neither Sheckard nor Cather hit particularly well in their starts; three of Cather’s 12 hits came in games he entered to replace Sheckard when the opposing team switched from the right-handed starting pitcher to a lefty reliever.14 The left-handed-batting Evans for the season predictably had more trouble in the 17 games he started against southpaws (.217 batting average), compared to what he hit (.261 batting average) in his 45 starts against righties.

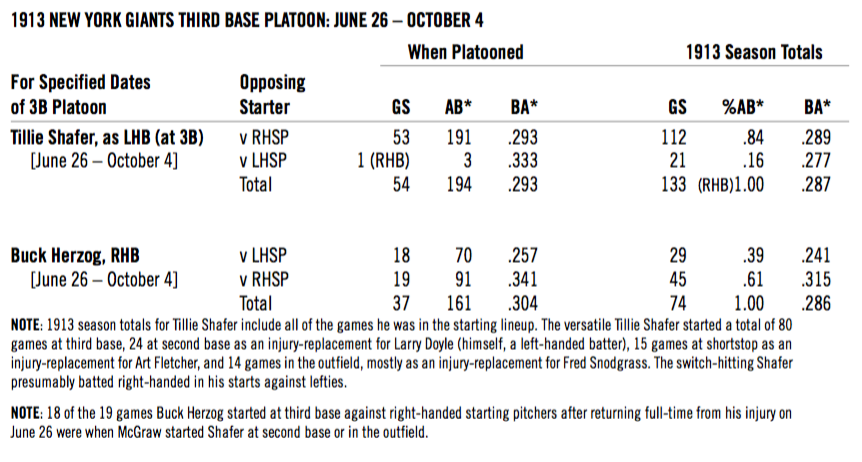

An injury to New York Giants third baseman Buck Herzog in late May paved the way for John McGraw, the master of in-game moves for tactical advantage, to try platooning. Herzog had started every one of the Giants’ first 35 games and was batting .258 when he got hurt and was limited to primarily a pinch-hitting role the next 27 games, starting just twice. McGraw made Tillie Shafer his third baseman during Herzog’s extended absence from the lineup from May 29 to June 26, knowing it would be a seamless transition; Shafer had started 18 of the Giants’ first 22 games as a substitute for Larry Doyle at second and Art Fletcher at shortstop when either was hurt, and 11 of the next 13 in center field because Fred Snodgrass was hurt and struggling. Shafer was batting .252 filling in for those guys, and responded to yet another change of position by batting .342 in the 27 games he started in place of Herzog.

By the time Herzog was finally ready to return full-time to the Giants’ starting lineup, McGraw had decided to platoon the two men at third. From then until the end of July, when Shafer was once again needed to fill in for Doyle at second base, McGraw platooned the two men at third base. The switch-hitting Shafer, batting from the left side, started the next 27 games in which a right-hander took the mound for the other team, batting .320 in those starts. The right-handed Herzog started just 8 games from June 26 to July 30, all but one against a southpaw, batting .281 in those starts. Except for whenever Shafer was needed to substitute for Doyle at second base or for one of the outfielders, which gave Herzog starting time against right-handers, McGraw continued his third base platoon for the rest of the year. Ironically, Herzog’s .341 batting average in his 19 starts against right-handed pitchers after returning from his injury was much better than the .257 he batted in his 18 starts against southpaws. McGraw did not platoon Shafer and Herzog in the 1913 World Series, perhaps only because he used the versatile Shafer in center field to replace Snodgrass, who was hobbled by a leg injury.15

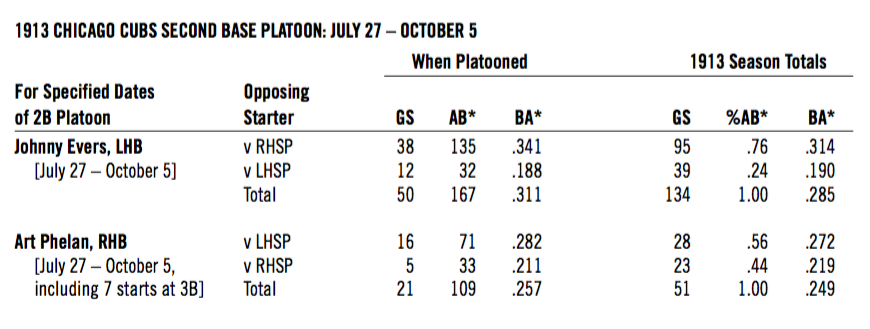

Chicago Cubs manager Johnny Evers, who like Huggins was a first-year player-manager, also used a platoon in 1913, but the position where he alternated a left-handed batter with a righty depending on the day’s opposing starting pitcher was his own—second base. Evers did not do so routinely, however, and did not begin excusing himself—a left-handed batter—from the starting lineup in games started by left-handers with frequency until late July. Johnny Evers was then playing in his twelfth major league season. Officially listed as weighing only 125 pounds at 5-foot-9 (which was an average height for American-born males in those days), the scrawny Evers was undoubtedly worn down and beaten up by years of playing a middle infield position, including takeout slides by baserunners. Personally finding left-handers particularly hard to hit this year— he batted just .190 in games against them, compared to .314 when a right-hander took the mound—if Evers was going to give himself a day off during the season, especially as the summer dragged on and the Cubs dropped out of contention, it was going to be against southpaw starters. Evers used right-handed-batting infielder Art Phelan in his stead when he did not start. Phelan, who also filled in at third base when Heinie Zimmerman was unable to play, batted much better against southpaws (.272), as might have been expected, than righties (.219).

Evers’s platooning of himself, however, was more episodic than consistent. It was not until the end of July, when the Cubs were 16 games behind and just two games above .500, that he began doing so on a more regular basis. Up till then he had started in 84 of his team’s first 91 games, including 27 of the 32 times a lefty started against the Cubs in which he batted just .192, compared to .296 in the games he started against right-handers.16 In the remaining 25 games the Cubs faced a southpaw in 1913, Phelan started 13 games at second base and Evers started himself 12 times.17 For the year, Johnny Evers started himself in all but three of the 98 games where a right-hander took the mound against the Cubs and in 39 of the 57 games when the opposing starting pitcher was a southpaw.

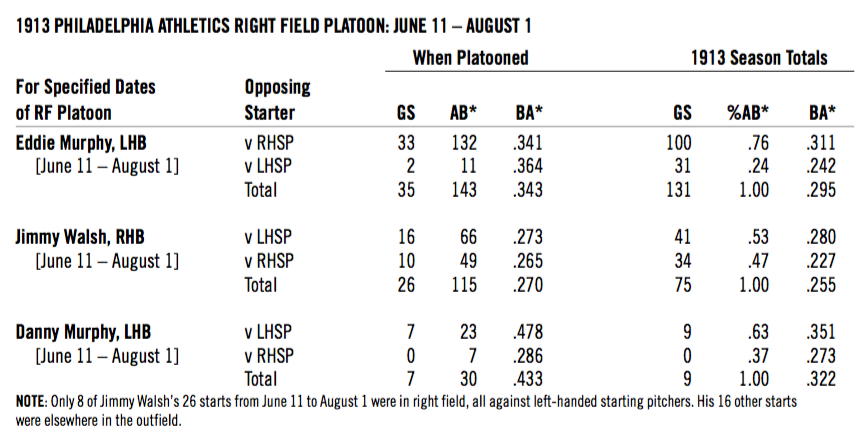

Over in the American League, Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack started platooning the left-handed-batting Eddie Murphy and the right-handed-hitting Jimmy Walsh in right field on June 11. There was no obvious reason for Mack to do so. Murphy had started in all but one of his team’s first 47 games and was batting .275 at the time, and in the 10 games where the Athletics had faced a southpaw, his .273 batting average was nearly as good as what he hit against righties.18 He had endured a two-week, 11-game stretch in mid-May when he batted only .190, but Mack kept him in the lineup and Murphy had recovered to bat .333 in the next 15 games when suddenly his manager decided on a right-field platoon. Walsh, who had started 13 of the 23 games he had so far played as a temporary replacement for center fielder Amos Strunk in early May, was batting just .211. For six weeks from June 25 to August 1, Murphy started each of the 28 games where a right-hander took the mound against the Athletics and made the most of his platoon advantage by batting .366—including 1-for-1 in a game he entered after a right-hander was brought in to relieve the lefty starting pitcher—and noneagainst lefties, while Walsh and veteran right-handed-hitting outfielder Danny Murphy, not only nearing the end of a career that began in 1900, but trying to make a comeback from a devastating knee injury the previous year, each started eight games in right field against southpaws. Although both Walsh and Danny Murphy hit much better against pitchers who threw from the opposite side they hit, Eddie Murphy was back to being Mack’s full-time right-fielder for the rest of the season after August 2, irrespective of the starting pitcher. Ironically, after being put back in the lineup on an everyday basis, Murphy batted poorly in his 19 starts against lefties (.192), but quite well (.325) in his 31 starts against right-handers.

That the Philadelphia Athletics were the only American League team to try platooning during the 1913 season is consistent with the fact that since 1911 the AL also lagged far behind the National League when it came to in-game position-player substitutions. While the average number of position-player substitutions because of pinch hitting and the subsequent need for a defensive replacement, or making a defensive change when the other team brought in a new pitcher in anticipation of future at bats, increased from 54.5 per team in the National League in 1910 to an average of 73 per team the next two years, there was only a modest increase in the American League from an average of 50.5 per team to 60 in 1911 and 1912. In 1913, the National League’s team average of 107 position-player substitutions exceeded the AL average of 73 by nearly 50 percent. Following in McGraw’s wake of using his bench strategically during games, National League managers seem to have been more comfortable with taking the next step of seeking a batter-pitcher advantage from the very beginning of the game. It is perhaps not surprising that Connie Mack was the only American League manager to platoon in 1913—and he did so for only a month and a half—since he had in recent years been making appreciably more position-player substitutions than the league average; in 1913, Mack made 81 position-player substitutions.

MATTERS OF CIRCUMSTANCE

None of the six clubs that platooned in 1913—Stallings’s Braves included—began the season doing so. These managers could not be certain of the strategy’s efficacy over the course of a full season and in every case except for Connie Mack’s decision to platoon Eddie Murphy, circumstances forced them to experiment.

-

Brooklyn: Manager Bill Dahlen concluding early on that rookie right fielder Benny Meyer was not ready for prime time.

-

St. Louis: an early-season injury to right fielder Steve Evans.

-

Boston: an early-season slump that Joe Connolly couldn’t seem to shake, plus in June manager Stallings deciding that veteran third baseman Art Devlin was no longer a prime time player.

-

New York: starting third baseman Buck Herzog getting hurt about one-fifth of the way into the season.

-

Chicago: manager Johnny Evers deciding that one-and-the-same second baseman Johnny Evers was having so much trouble against left-handed pitching that it would be best if he play much less often when his team faced a southpaw.

With few exceptions, the players who were platooned in 1913 were either over-the-hill veterans like Jimmy Sheckard, Art Devlin, John Hummel, and Danny Murphy, or players with limited major league experience who went on to have relatively short or undistinguished journeyman careers.

-

The Cardinals released 34-year-old Sheckard in mid-summer and, although he was picked up by Cincinnati, he retired after the season ended. Thirty-three-year-old Devlin was also released during the summer and likewise officially retired after the 1913 season. Hummel was 30 years old in 1913 and played just 126 games the next two years before disappearing into the minor leagues. And Danny Murphy, 36 years old, was cut by Connie Mack after the season and resurfaced in the Federal League for 52 games in 1914 and 5 in 1915 to end his big-league days.

-

As for the young players or those lacking big-league experience, Tillie Shafer left the game after 1913 to go into the family business; the major league careers of Tex McDonald, Ted Cather, Herbie Moran, and Art Phelan came to an end in 1915; Joe Connolly’s big-league career lasted until 1916; Jimmy Walsh’s lasted until 1917. Eddie Murphy was a full-time regular in 1914 and 1915 before reverting to a primarily off-the-bench role for the remainder of a career that was basically over by 1920. Tommy Griffith stayed in the major leagues until 1925, mostly in a platoon role playing at barely above the level of performance that would be expected of a replacement-level player.

Two players who were platooned—some of the time—would ordinarily have been day-to-day regulars. Evers, probably feeling that as a player-manager he had enough to worry about without trying to hit left-handed pitching, gave himself 18 days off when a southpaw took the mound. Whatever Evers’s difficulties against left-handers may have been in 1913—and there is no doubt he had trouble since he batted below .200 in games started by southpaws while batting over .300 in games when a righty took the mound— the next year when he was with the Braves, he was not platooned by Stallings. In 1914, Evers batted a respectable .244 in 47 starts against left-handers—the Braves faced a southpaw starting pitcher in 56 games—compared to .297 against right-handers, and he won the NL Chalmers Award as most valuable player for his role in Boston’s “miracle” season.

The Giants’ Buck Herzog, who got hurt while Shafer got hot and was platooned thereafter except when Shafer was asked to play another position, had a contentious relationship with manager McGraw.19 There was no other year in his career after Herzog became established as a regular in 1910 that he was platooned. For the years that batting splits are available on Baseball-Reference.com—1913 till the end of his career in 1920—Herzog, a right-handed batter, actually hit for a higher batting average (.259) in games started by right-handed pitchers than he did (.246) when a southpaw took the mound. About three-quarters of the games he started were against right-handed pitchers.

ASSESSING STALLINGS’S ROLE

If 1913 was a year in which managers “experimented” with the concept of platooning, then it is instructive to note that George Stallings and Connie Mack were the only two managers whose platoon decisions seemed to be more a concerted strategy to play the percentages for advantage, rather than compensating at a position of weakness caused by injury or poor performance. Evers platooned for the percentages as well, but his was a unique case because he was the manager, and even after he became more committed to the concept he started himself nearly as often against southpaws as he did the right-handed Phelan. Either way, Evers-the-player almost certainly would not have been platooned by any other manager—he certainly wasn’t by Stallings in 1914—and might have objected vociferously had any manager other than himself tried to platoon him.

If 1913 was a year in which managers “experimented” with the concept of platooning, then it is instructive to note that George Stallings and Connie Mack were the only two managers whose platoon decisions seemed to be more a concerted strategy to play the percentages for advantage, rather than compensating at a position of weakness caused by injury or poor performance. Evers platooned for the percentages as well, but his was a unique case because he was the manager, and even after he became more committed to the concept he started himself nearly as often against southpaws as he did the right-handed Phelan. Either way, Evers-the-player almost certainly would not have been platooned by any other manager—he certainly wasn’t by Stallings in 1914—and might have objected vociferously had any manager other than himself tried to platoon him.

McGraw’s third-base platoon involving Shafer and Herzog seemed more experimental than necessarily strategic because both were capable of being everyday players against any pitcher, and indeed both often played different positions in the same game with Herzog at third and Shafer wherever else McGraw might have needed him. McGraw probably went with it because, since Shafer was playing so well, he had little to lose by trying out a third-base platoon.20 Perhaps noteworthy is that McGraw made fewer position-player substitutions in 1913 (130) than the year before (163 in 1912) for the first time since 1906, suggesting both the advantage of Shafer, at whatever position he started, being a switch-hitter, and that platooning in his starting lineup sometimes made it unnecessary to pinch-hit or make a position substitution he might otherwise have at a critical moment later in the game.

Most revealing about Stallings, and indicative of his taking a more thoughtful and forward-looking approach than any of the other managers who used a lefty/righty split at any one position that year, was his decision to platoon Joe Connolly. Although he was already 29 because he had gotten a late start in the established minor leagues, the left-handed-batting Connolly was highly regarded when he came to Boston as a rookie in 1913.21 He was expected to be an everyday player. When Connolly got off to a rough start, however, and seemed particularly flummoxed by left-handers, rather than benching him in favor of someone else, Stallings chose instead to limit his supposed-to-be-good-hitting outfielder to starts against right-handed pitchers. Connolly in fact was a regular in Stallings’s lineup for the remainder of the 1913 season, and for the next three years as well—but only in games a right-hander took the mound against Boston, with very few exceptions. Once Stallings decided to platoon him, Connolly never got a chance in his four brief years with the Braves to prove he could hit left-handers.

Joe Connolly played his entire four-year major league career for the Boston Braves under George Stallings. Only 19 of his 322 career starts were against left-handers, just five after 1913. Stallings, however, inserted him into 48 other games that a southpaw started against Boston, almost always to get his dangerous bat into the game when a right-hander was brought in as a relief pitcher. Perhaps validating Stallings’s apparent judgment that Connolly would not be successful against left-handed pitching, Connolly batted just .209 in the 67 career games he played that the Braves faced a southpaw starting pitcher, compared to .298 in games where the opposing team started a right-hander.

If 1913 was a proof of concept year for platooning, the payoff of such a strategy seemed to generate mostly a collective shrug. There does not appear to have been any meaningful attention brought to that particular lineup strategy, even if baseball writers were aware it was happening. But that is not necessarily surprising. It was, after all, just baseball. Moreover, most of the players involved in the 1913 experiments were over the hill or just getting started. A player who was being platooned was unlikely to be an impact player; if he was an impact player, he would have been an everyday starter. Among those platooned who were closest to being impactful players, the veteran Evers and the rookie Connolly were both left-handed batters who would be in the starting lineup most days anyway because most pitchers were right-handed. Shafer’s ability to play multiple positions had him starting somewhere most of the season, masking the fact that for much of that time he was actually part of a platoon. Herzog had endured an injury and started often enough when he was in fact being platooned because Shafer was in the lineup at some other position that it went largely unnoticed, if noticed at all, that he was frequently not in the lineup against right-handed starting pitchers. Proof of concept was almost certainly also undermined by players’ resentment about being platooned. Herzog was known to be unhappy about his playing time, and it seems likely that so too was Eddie Murphy, perhaps causing Connie Mack to end his right-field platoon at the beginning of August.22

While Stallings was far from alone in trying out platooning as a starting lineup strategy in 1913, he was perhaps the most perceptive and committed as to its effectiveness. Of the six teams that platooned in 1913, only the Braves, Cardinals, and Giants did so in 1914, and neither Cardinals manager Huggins nor McGraw began the season with a platoon at any position.23 Stallings by contrast was clearly sold on the value of platooning at positions of weakness. He did so in 1914 from the beginning of the season at both corner outfield positions, and eventually platooned his entire outfield. Had it not been for the stunning success of the Braves surging from last place on the Fourth of July to overtaking John McGraw’s favored New York Giants in early September, winning the National League pennant decisively, and following up with the first four-game sweep of a World Series against Connie Mack’s heavily-favored Philadelphia Athletics, “the concept would probably have remained relatively obscure until some team did win using a platoon system.” That was a key judgment in my article on “The 1914 Stallings Platoon.” It still seems a fair one.

BRYAN SODERHOLM-DIFATTE is the author of “The Golden Era of Major League Baseball: A Time of Transition and Integration” (Rowman & Littlefield, 2015). He also writes the blog, Baseball Historical Insight, and is a frequent contributor to SABR publications. He does not have a favorite team — he just loves baseball, particularly its history — but grew up in New York, went to college in Los Angeles, and graduate school in Boston, and lives in the Washington DC area, within easy distance of Baltimore, all of which provide a fair indication of the teams he most closely follows.

Notes

1 Retrosheet’s “regular season game logs” for 1913 at that time included the starting pitcher and opposing starter for each game, but did not include box scores because the research effort had yet to be completed. The Retrosheet page for each team, however, did include the total number of games played by each player and at every position. While the lack of box scores for Braves games in 1913 made it impossible to analyze Stallings’ starting lineups specifically, the distribution of games by Braves outfielders in left, center, and right, combined with knowing which side of the plate each batted from and who the opposing starting pitchers were—including the number of games started by both righties and lefties—provided a basis for trying to determine whether Stallings platooned that year. My analysis at that time was based on correlating the number of specific games played by Braves’ left-handed-hitting outfielders with the number of times left-handed pitchers started against them (and, of course, the other way around). It should be emphasized that in the absence of box scores, such indirect correlations would necessarily be imprecise, but they could nonetheless provide insight into whether or not Stallings was platooning in 1913.

2 Note that Baseball-Reference has not yet aggregated the starting line-ups for 1911 and 1912 for any team on its site. Since the data for 1911 and 1912 is not yet aggregated into easily-accessible game-by-game “starting line-up” data, I relied on Retrosheet’s calculus of players’ position games started + their complete games, and by cross-checking with box scores, I was able to determine that in every case where it looked like there might be a platoon, there was not. Players who did not hold down their position for the entire year were always in the starting line-up for big chunks of time.

3 As Tom Nawrocki points out in “Captain Anson’s Platoon,” The National Pastime, Issue #15 (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1995), the small size of rosters would have been a hindrance to platooning in the nineteenth century. He suggests that Anson’s splitting of playing time based on handedness may have been his way of solving the “problem” of overabundance of starting talent on his roster and that the practice did not extend beyond the 1886 season. Even after rosters grew in the first decade of the twentieth century, other than swapping in catchers, who could not catch every game, managers fielded their best players every day, while those on the bench were reserves in case of injury, not strategic advantage. The premium was still on fielding the best players, and for reasons of both pride and paydays—especially the money—no player in a starting role wanted any part of being systematically kept out of the line-up because of who was pitching for the other team. And all managers, including McGraw, preferred the certainties of a set daily line-up.

4 That comes with the caveat that in some prior years, teams that had both a left-handed-batting and right-handed-batting catcher would sometimes platoon them in the starting lineup, as the Giants’ John McGraw did with Jack Warner, a lefty batter, and Frank Bowerman, a righty, for much of 1903 and 1904. To the extent any teams thought of platooning in the first half of the Deadball Era, it was with regard to catchers because the rigors of the position at a time when equipment offered much less protection from being battered and beaten by foul balls necessitated they needed many more days off than other position regulars, and platooning offered an opportunity for doing so. All other position regulars at the time were expected to be everyday players, removed from the starting lineup only if they were hurt, slumping, played themselves out of the job, or needed a very occasional day off.

5 Position-player substitutions are derived from the difference between total position games for a team during the season and the total number of games times the eight fielding positions (pitcher not included). This figure does not include pinch-hitters for position players who did not subsequently take the field in place of the player they batted for, either because another player went in as the defensive substitute (who counts as the position-player substitution) or because pinch-hitting for the position player occurred in the bottom of the final inning of play and hence did not require a defensive replacement. These data are available at Retrosheet.org.

6 Devlin had been the third baseman for McGraw’s Giants from 1904 until his sale to Boston just before the start of the 1912 season. He played 69 games at first base, 26 games at shortstop, and 26 games at third for Boston that year, while McDonald played 118 games at third.

7 Lord, meanwhile, flourished as Titus’s replacement in right field between July 19 and August 16, batting .303 in 21 starts, including 16 against right-handers, until Stallings decided to once again use him in a platoon role for the rest of the season.

8 The left-handed-batting Zinn batted .286 in the 7 games he played started by a southpaw, including one when he entered the game after a right-handed reliever came in, and .300 against right-handed starters. Zinn finished the season with a .297 batting average in 36 games but took himself out of the running for a starting position on the 1914 Braves when he opted for the Federal League instead. After the Federal League folded in 1915, Guy Zinn did not play another game in the major leagues, although he did play six more years in the minors.

9 Connolly also appeared in 9 games that he was not in the starting lineup when a southpaw took the mound for the other team. In each case, he came in after a right-handed pitcher had entered the game. He had just 2 hits in 17 at bats in those games, which accounts for his .164 average in Braves’ games started by a left-hander that appears in the table on the “1913 Boston Braves’ Outfield Platoons” for Connolly’s 1913 season totals, even though he hit .182 in the games against southpaws that he was in the starting lineup.

10 Just to be clear, Tex McDonald and Ed McDonald, who played third base the previous year, are not the same person.

11 Smith started the last 9 games of the year at shortstop after Rabbit Maranville was injured with Charlie Deal taking over at third the rest of the way.

12 Leveraging his .359 batting average with the Braves for a better deal in the upstart Federal League in 1914, Tex McDonald played for the Feds in 1914 and 1915 and never again played in the major leagues after that. Fred Smith also defected to the Federal League, played two years there, had to settle for a minor-league gig in 1916, appeared in 56 games for the Cardinals in 1917, and disappeared thereafter from the annals of major league baseball.

13 Sheckard had been an elite hitter for Brooklyn at the turn of the century and had led the league in walks the two previous seasons, 1911 and 1912, playing for the Cubs. He was now 34 years old, however; Cather was 10 years younger

14 The Cardinals were also able to platoon behind the plate because Ivey Wingo, in his third year and clearly up to being a regular, was a left-handed batter, allowing Huggins to give him days off when a southpaw started against St. Louis in favor of right-handed-hitting Larry McLean and, later, Palmer Hildebrand. Huggins did not necessarily platoon his catchers as matter of routine, however; 20 percent of Wingo’s starts were against lefties, and 35 percent of McLean’s against righties.

15 Shafer started four of the five games in the 1913 World Series against the Philadelphia Athletics in center field in place of the injured Snodgrass, except for Game Four when he started at third base. In that game, however, Snodgrass was forced to leave the game in the third inning,causing McGraw to move Shafer from third into center and bring in Herzog to play third base. Shafer went 3-for-19 in the Series, and Herzog—the Giants’ batting star in the 1912 World Series—had just one hit in 19 at bats against Philadelphia’s pitching.

16 Evers started himself at second base in all but two of the first 59 games his team played when a right-hander took the mound against them.

17 There were also three games that a southpaw started against the Cubs where Phelan was in the starting lineup at third base in place of Zimmerman, with Evers at second. It seems likely in context that if Zimmerman had been able to play, Evers would probably have started Phelan at second base instead of himself.

18 Murphy had come up in late August the previous year and played right field in 33 of the Athletics’ final 35 games, batting .317 to earn himself the starting job in 1913, at least until Mack decided to try him in a platoon role.

19 Richard Adler, Mack, McGraw and the 1913 Baseball Season (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2008), 200. Adler notes there was significant tension between McGraw and Herzog that year. Joseph Durso, The Days of Mr. McGraw (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1969), 59. Durso writes that McGraw “detested” Herzog.

20 Tillie Shafer’s 2.9 wins above replacement in 138 games was the fourthhighest among Giants’ position players in 1913. Herzog’s player value was 2 wins above replacement, but he played just 96 games.

21 Connolly impressed major league scouts by batting .316 for Montreal in the International League the previous season. Contemporary baseball writer Samuel M. Johnston in his profile on the Braves’ outfielder, “Good Natured Joe Connolly, The Man Who Always Smiles,” in the February 1915 issue of Baseball Magazine, page 27, made a point of noting that Connolly “never had any trouble hitting the southpaws in the minors.”

22 Adler, 200.

23 Huggins started the 1914 season with left-handed-batting Walton Cruise as the Cardinals’ everyday left fielder before reverting to a platoon arrangement in early May. With Herzog traded to Cincinnati and Shafer having left the game, McGraw was forced to find a new third baseman entirely. Rookie Milt Stock was his man. A right-handed batter, Stock started virtually every game at third through August before an injury all but ended his season. From mid-June till the end of the season, McGraw platooned rookie left-handed-batting Dave Robertson with left-handed-batting veterans Fred Snodgrass and Red Murray in the outfield, usually right field, until the end of the season.