The Struggle to Build Dodger Stadium

This article was written by Andy McCue

This article was published in Dodger Stadium: Blue Heaven on Earth (2024)

Dodger Stadium, opened in 1962, is located just north of downtown Los Angeles. (Copyright Wirestock /dreamstime.com)

It’s easy to look up at the stadium on its hill overlooking Los Angeles and see nothing but easy – the location, the design, and, above all, the year-after-year attendance. But the process of winning the right to build Dodger Stadium was a four-year grind through dogged opponents and naïve and dilatory politicians.

In the beginning, it did seem easy. In February 1957, Walter O’Malley announced he had paid $3 million for the Pacific Coast League’s Los Angeles Angels and their ballpark, Wrigley Field. Under baseball rules, this gave him the rights to the Los Angeles market. Within two weeks, Los Angeles Mayor Norris Poulson and LA County Supervisor Kenneth Hahn organized a six-person delegation to meet O’Malley at the Dodgers’ Vero Beach, Florida, training site.

It was a lopsided meeting. The Los Angeles delegation, brimming with enthusiasm and frustrated after nearly two decades of misses in their desire for major-league baseball, were willing to discuss anything. O’Malley, a veteran of stadium operations and major-league politics, knew what he wanted – land to build a stadium and parking lots he could control. He suggested multiple possibilities – a city-built stadium, a long-term lease for the land, government-provided grading, freedom from property taxes, $1 annual rent on the Los Angeles Coliseum while the stadium was built. Every time he suggested something, including 500 acres near downtown, the local politicians indicated it was very possible.

Poulson emerged from the meeting full of smiles. O’Malley was less fulsome, taking the podium after the mayor and saying, “I’ll take the edge off that right now.” Both described the talks as throwing out ideas and said the discussion was far too preliminary to make public.1 Poulson continued to ooze confidence, saying all problems were solvable. Upon his return to Los Angeles, he was quoted as saying, “We’ve got the Dodgers,” but he quickly backed away.2

It would become clear over the next months that the two parties really had not communicated. When the Los Angeles delegation got home, reality set in. The city attorney pointed out that the Los Angeles Coliseum Commission, which controlled the facility, had not been represented in Vero Beach and would not have to honor any promises. There were still questions about the city’s title to the Chavez Ravine acreage O’Malley wanted. The federal government had given it to the city with the restriction it had to be used for a “public purpose.” Robert Moses had used similar limits on federal money to deny O’Malley’s desire for aid in putting together a ballpark site in Brooklyn.3 Los Angeles officials had to go to Washington, D.C., for assurances that a deal for the land was legal. Other issues appeared.

Over the next few months, O’Malley clarified his list of desires and the city named former Eisenhower administration official Chad McClellan to work out an agreement. By September the major issues had been settled. The city would provide “about” 300 acres in the Chavez Ravine area and up to $2 million in city and county investments, mostly in infrastructure near the ballpark. In return, the Dodgers would turn over the Wrigley Field property, which the city wanted for a public park, and lease 40 acres on the stadium site for another park and spend up to $500,000 for building facilities on that site, plus $60,000 in upkeep annually for 20 years. The Dodgers would also give up half the mineral rights on the site.

Los Angeles County supervisor Kenneth Hahn and Los Angeles City Councilwoman Rosalind Wyman welcome Walter O’Malley at Los Angeles International Airport on October 23, 1957, as O’Malley arrives to set up headquarters for the Los Angeles Dodgers. (SABR-Rucker Archive.)

In the Los Angeles area at that time, mineral rights were a hot-button issue. In earlier decades, oil finds in Signal Hill and Santa Fe Springs had given some people backyard wealth and others dreams of it. In the stadium negotiations, the rights became an issue that far exceeded reality. The city council bloc opposed to the contract demanded that a site within the acreage be set aside for drilling. O’Malley had checked with oil industry people who had told him the potential of Chavez Ravine was negligible. He stood to lose little but was getting exasperated, saying he was getting the feeling he wasn’t wanted, just as he felt in New York.4 He demanded half the profits any wells might produce but said the money would go to youth sports programs.

On Sunday, October 6, 1957, Councilwoman Rosalind Wyman, the point person in attracting the Dodgers, called O’Malley in Brooklyn. She described the uncertain political situation for a final vote scheduled for the next day. She said the Dodgers’ case could be strengthened if O’Malley promised that a favorable vote would guarantee that the team would come. O’Malley refused. The council did approve the contract and the next day O’Malley said the team would move.

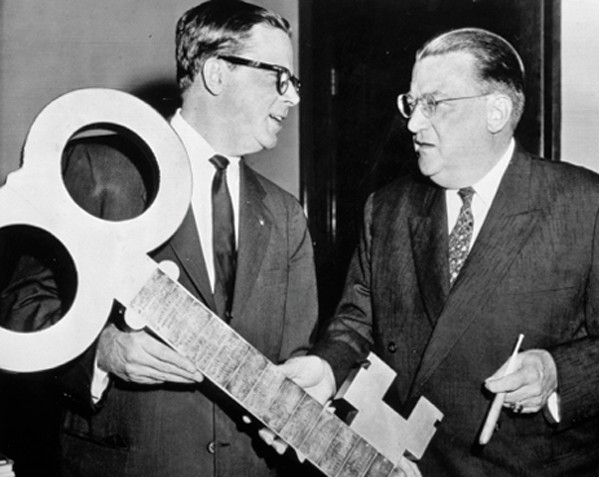

Los Angeles Mayor Norris Poulson presents key to city to the Dodgers’ Walter O’Malley. (SABR-Rucker Archive.)

For much of Los Angeles, the move was a momentous validation of its status as a “major league” city. O’Malley’s reception at the airport later in October was rapturous. As the Dodgers organization ramped up later in the year, ticket requests were overwhelming.

But the opposition was not going away. At the airport, a man shouldered his way to O’Malley in front of the TV cameras. He presented O’Malley with a summons. There was already a taxpayers’ lawsuit even before the city council had agreed on its final offer. By December 5, it was announced that a referendum challenging the contract had qualified for the ballot in June 1958.

The opposition was a grab-bag of interests. The public face was City Councilman John Holland, whose highly conservative politics were offended by any public money being spent on a private enterprise. Other councilmen, from distant districts in the spreadeagled city, saw the stadium as a ploy to build up downtown Los Angeles to the detriment of their areas, a view echoed by some of the suburban newspapers. Movie theater owners saw the Dodgers as competition.

Holland argued that the city was losing a valuable piece of land near the city center. While tax records showed a higher value for the Wrigley Field parcel than for the Chavez Ravine land, there was no doubt that the stadium parcel had much more potential. But Holland’s attempts to promote a “world scientific exposition” or a cemetery for the site found little support.5

The antis weren’t making much progress in the city council, but they did persuade the California State Assembly’s Interim Committee on Governmental Efficiency and Economy to hold hearings. One day of testimony saw both sides reiterate their positions on the contract. The only new wrinkle was John Smith, owner of the minor-league San Diego Padres and a major financier of the antis’ effort, who made an offer to pay the city for the oil rights. When the city took him up on the offer, he began putting conditions on it, and no other oil company stepped forward to accept the terms. Profitable levels of oil have never been found under the stadium land. The Assembly committee never issued a report.

At first, Poulson and O’Malley decided to ignore the referendum campaign, especially when their polls indicated that two-thirds of voters supported the contract. But the drumbeat of criticism and the Assembly hearings were having their effect. Polls showed that support had fallen to 37 percent. O’Malley and Poulson began pressing the case.6

Speeches to civic groups multiplied. Poulson declared a Dodger Week. In April, O’Malley backed off his refusal to televise Dodgers games, scheduling the broadcast of a series in San Francisco in early May.7 The Los Angeles Times redoubled its support in both editorial and news columns. On the Sunday before the vote, the Times-owned Channel 11 staged a five-hour “Dodgerthon” with celebrities joining O’Malley in supporting the stadium contract. It worked, barely, with the stadium deal affirmed by 51.8 percent of voters.

O’Malley’s fears of further legal entanglements for his stadium were confirmed all too quickly. On Wednesday, June 4, 1958, with the win for Proposition B confirmed, O’Malley was talking of construction work within a month. On Friday, June 6, Superior Court Judge Kenneth Newell issued a preliminary injunction blocking the city from transferring the Chavez Ravine land to the Dodgers.

The referendum had asked voters if the stadium deal was good for the city; the taxpayers’ lawsuit alleged that the deal was illegal. The key issue raised by the taxpayer suit’s attorney, Phill Silver, was highly similar to the argument Robert Moses relied on in New York – whether aiding a private corporation constituted a “public purpose.” The Los Angeles trial was unusual because there were few issues of fact involved. It would focus on whether the provisions of the city council’s contract with the Dodgers conformed to law.

As the trial progressed, Judge Arnold Praeger forced the lawyers for the city, the Dodgers, and Silver to focus on whether the contract gave the team too much authority in deciding exactly how to spend city money and whether the city could close public streets for the benefit of a private corporation. He also raised the broader “public purpose” issue.8 On July 14 his decision came down squarely against the Dodgers. It was illegal, he ruled, for the city to transfer land formerly designated for public housing (a public purpose) to the Dodgers, a private corporation. It was illegal for the city to pledge to spend public money to acquire more land in the area to be given to the Dodgers, to close streets for the benefit of a private corporation, to delegate to the club decisions on exactly how to spend public money provided for grading, and how to spend the money for parks raised by any oil revenues. On the public-purpose issue, he said the city council had exceeded its authority.

“I remain an optimist,” O’Malley said. “This is just another hurdle which we will have to take in stride. What hurts is the delay. Our timetable is out the window and I’m afraid San Francisco will have its new stadium first.”9 With fans still bringing their money to the Coliseum, Time magazine said Los Angeles was the “Garden of Eden and the Black Hole of Calcutta rolled into one” for O’Malley.10

The first decision to be made was how to use the appeals process. The city and the Dodgers’ attorneys calculated that an appeal couldn’t be completed before 1960. With construction time tacked on after that (and the unspoken thought that any California decision might be appealed to the US Supreme Court), it looked unlikely that the Dodgers could have their stadium until late in the 1962 season. Instead, the Dodgers/city team made the decision to seek a writ from the California Supreme Court to prohibit enforcement of Praeger’s decision.

On October 15, 1958, the California Supreme Court granted the city and the Dodgers a temporary writ of prohibition, but didn’t render a final decision until January 13, 1959, when it unanimously overturned Praeger’s decision. The justices looked at the contract in an entirely different way than Praeger had. “In considering whether the contract made by the city has a proper public purpose, we must view the contract as a whole,” wrote Chief Justice Phil S. Gibson. “The fact that some of the provisions may be of benefit only to the baseball club is immaterial, provided the city receive benefits which serve a legitimate public purpose.”11

O’Malley was bubbling. Groundbreaking for the new stadium, he said, would happen within 30 days. It would be open for the 1960 season, although it might have only 32,000 of its seats at that point, with more being added as time went on.12 By the next day, reality had set in again. City Attorney Roger Arnebergh said O’Malley had been “extremely optimistic,” noting that it would take a minimum of 60 days to clean up the paperwork and get the city/Dodgers contract signed. Only then could the Dodgers begin the process of submitting documents to the City Planning Commission. County Supervisor Frank Bonelli predicted that the stadium wouldn’t open until 1964 as opponents would keep throwing up roadblocks. Silver said he would appeal.

In February and again in April, the top California court rejected Silver’s pleas – first for a rehearing and then to overturn the earlier decision. The latter was the last gasp in state courts, but Silver indicated he was willing to appeal to the US Supreme Court. Since the Supreme Court didn’t even come back into session until October, the delay would stretch for months more. The city/Dodgers contract was formally signed on June 3, 1959, the first anniversary of the referendum victory and 20 months after the city council first approved its terms. Barely three weeks later, on the eve of O’Malley’s proposed July 1 groundbreaking, Silver appealed to the US Supreme Court.

On Monday, October 19, 1959, the Supreme Court sped up the process enormously. It declined to hear Silver’s appeal, giving no reason. O’Malley, pleased but properly chastened after nearly 2½ years of fighting for what he thought he’d been promised in February 1957, said he hoped there would be no more “political” delays. Delay, he said, already had added to the projected cost of the stadium and pushed its debut far beyond Opening Day 1960 as he had planned.13 He hoped the ballpark would be ready for Opening Day 1961, with maybe some games late in 1960.

By Wednesday morning, O’Malley had Dick Walsh deliver stadium plans to the city to support a request for necessary zoning changes on the Chavez Ravine land. Immediately, there were problems. The plans weren’t as specific as City Councilman Ransom Callicott, chairman of the council’s planning committee, wanted. Callicott also noted that the plan included a number of commercial enterprises – a gas station, a car wash, and several restaurants – that had not been anticipated. Callicott, who’d been a consistent Dodgers supporter on all the earlier votes, indicated that he was troubled by these unexpected additions.14 Within a few days, more exact maps came back. The car wash was gone. The restaurants – a fast-food outlet, an outdoor luau-type arrangement, and a sit-down restaurant – had been moved inside the stadium structure. The gas station was still there. O’Malley said it had been requested by city planners as there were no others in the immediate area.

The changed plans won the zoning approval requested, but not before another uncomfortable afternoon in city council chambers. After the council dithered through several procedural issues, O’Malley rose to say that the referendum and the lawsuits already had pushed the stadium back so far that the cost had risen by $3 million. “I cannot afford to have this drag on,” he concluded. The council voted approval.15

The city’s dilatory ways had already created another controversy, one that still echoes to this day.

In May 1959, sheriff’s deputies evicted a Mexican American family named Arechiga from their home on the Chavez Ravine property and tore the house down. The scene, with dramatic film, played big on Los Angeles’ television stations.16

If a picture is worth a thousand words, these needed a thousand words of context. The Chavez Ravine property had been designated for public housing in 1950. The Los Angeles Housing Authority began eminent-domain proceedings against the landowners, including the Arechigas, and $10,050 was deposited in an escrow account while title was transferred to the city. By 1953, the Chavez Ravine community, which once had numbered 1,100 families, was down to the Arechigas and perhaps 20 other holdouts.

Events had overtaken the Housing Authority. Conservative groups around Los Angeles, including the real estate industry, the Chamber of Commerce, and the Los Angeles Times, rallied against public housing. The city council abrogated its contract with the Housing Authority. In a June 1952 ballot measure, 60 percent of voters said they wanted no part of public housing.

In 1953 the Arechigas sued to regain title, citing the death of the public-housing proposal. The resulting court battle was decided in the city’s favor. The Arechigas, still hoping to retain their home, did not accept the money. And the city, uncertain what the land could be used for, did nothing to enforce the judgment and take over the property. The incident went into public memory as poor Mexican Americans thrown into the streets to build Dodger Stadium even though the land had originally been taken for public housing.17

Work picked up. But by early 1960, it was clear that yet another of the city’s casual procedures was about to cause problems. As with the Arechigas and their neighbors, this was a fistful of property owners whom the city hadn’t dealt with as promised. They owned homes and one small store, that hadn’t been included in the Housing Authority’s land. They should have been bought as part of the city’s 1957 deal with the Dodgers. The city had started eminent-domain proceedings but dropped them.18 There had been some desultory bargaining but that had stalled. The city didn’t want to budge too far from the pre-Dodgers’ assessed value and the homeowners knew that with the bulldozers tearing up the hill above them, their properties had skyrocketed in value.

Caught between the city’s casual attitude and his timetable, O’Malley bit his tongue and paid. There were a dozen lots involved. All the property owners had hired the same attorney and promised that none would break ranks. The dozen lots had been assessed at $82,850 during the eminent-domain proceedings. O’Malley paid $494,400.19

By the time escrow closed on these houses, O’Malley was forced to concede that the stadium wouldn’t be ready for Opening Day 1961. For another month, he held out hope for July 1961, but then agreed it would take at least until Opening Day 1962. “I can’t tell you when we can open the park. It depends on how long are the delays that may be caused by our dedicated opponents,” he said. Asked if the Dodgers could learn anything from the problems popping up at the newly opened Candlestick Park in San Francisco, he said, “The way things are going, we will have more than ample time.”20

He did. As every Dodger-related piece of paper entered the city council, John Holland and his supporters found a way to delay. When the question of closing city streets in the Chavez Ravine area arose in August 1959, everybody in the council except Holland treated it as pro-forma. Holland voted no.21 The lack of a unanimous vote automatically forced a second reading and a delay of another two weeks. In May 1960 it was approval of a tract map for the stadium. In June it was an appropriation to buy a former elementary school site on the property from the school district. In July O’Malley’s supporters on the council were finally able to get an escrow on the Chavez-Ravine-for-Wrigley-Field exchange set up and approved. In August the city granted a conditional-use permit for the property, which would automatically turn into a building permit 10 days later unless an appeal was filed. With 15 minutes left in the appeal period, Silver filed one. A little over a week later, the appeal was overturned, but August had been lost to construction as well. In October the Dodgers and the city finally swapped land titles. In December the council gave approval to the final tract map, with Holland voting doggedly against each of the four necessary motions. The key vote was 18 to 1, Holland’s remaining supporters having thrown in the towel.22

It was the October 1960 swap of land titles that had really allowed construction to get going. But even as construction progressed, there were further difficulties with the city. A stadium hadn’t been built in Los Angeles since Wrigley Field in the 1920s, noted Dodgers executive Fresco Thompson, and nobody in the city inspector’s office had any experience with a stadium project. With the knowledge that Holland and other opponents were looking for issues to jump on, the inspectors had to be very thorough. They insisted that a sewer line be increased in size because a zoo might be built in neighboring Elysian Park. (It wasn’t.) They required that each car be given a separate parking slot so people could leave easily during games (the two major arenas where the city had a voice, the Coliseum and the Hollywood Bowl, both allowed parking cars bumper to bumper).23 “We had almost as many city officials swarming over the park as we did contractors’ workmen. You couldn’t tell ’em without a scorecard,” Thompson said.24

Then there was the phantom road. The city insisted that a route across the construction site be kept open even though it would disappear once the stadium opened. In fact, the city required the Dodgers to build a finished road, complete with curbs and streetlights. The road was used for 109 days before being torn up. It cost the Dodgers $59,742.25

Finally freed from the processes of the city, construction progressed. Dodger Stadium finally opened on April 10, 1962, two years later than O’Malley had planned.

As the construction process stumbled to its end, O’Malley was fed up. “One of the biggest mistakes I made when I came West was taking Western politicians at their word. I had been informed that a Western politician was a hearty, candid fellow whose handshake was his bond. I learned otherwise,” he said years later. “I didn’t expect a double-cross.”26

ANDY McCUE, a former president of SABR, won the Seymour Medal for Mover and Shaker: Walter O’Malley, the Dodgers, and Baseball’s Westward Expansion. He is also the author of Baseball by the Books: A History and Complete Bibliography of Baseball Fiction and Stumbling Around the Bases: The American League’s Mismanagement in the Expansion Eras (University of Nebraska Press, 2022). He is a retired newspaper reporter, editor, and columnist and a winner of SABR’s highest honor, the Bob Davids Award.

Notes

1 Frank Finch, “L.A. Officials Hopeful After Secret Session,” Los Angeles Times, March 7, 1957: C1.

2 Frank Finch, “Bum-Giant Feud Due to Move Here,” Los Angeles Times, March 10, 1957: 1.

3 Neil Sullivan, The Dodgers Move West (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987).

4 H.C. McClellan, “McClellan Tells ‘Full Truth’ of Dodgers’ Coming to L.A.,” Los Angeles Times, August 25, 1963: J1.

5 “Chavez Ravine Baseball Foes Present Ideas,” Los Angeles Times, January 14, 1958: C1.

6 “O’Malley Sees Start on Park by July 5,” Los Angeles Times, June 5, 1958: C1.

7 Televising only road games in San Francisco would remain the team’s policy for nearly two decades.

8 Gene Blake, “Judge Questions Chavez Contract,” Los Angeles Times, June 25, 1958: 2.

9 Frank Finch, “Extra-Inning Legal Tussle Looms Over Dodger Park,” The Sporting News, July 23, 1958: 10.

10 “Ravine Roadblock,” Time, July 28, 1958: 55.

11 Gene Blake, “High Court Approves Dodgers Chavez Pact,” Los Angeles Times, January 14, 1959: A1.

12 Mal Florence, “Dodgers to Open ’60 Season at Chavez Ravine,” Los Angeles Times, January 14, 1959: C1.

13 Carlton Williams, “Supreme Court Approves Dodger Chavez Park,” Los Angeles Times, October 20, 1959: A1.

14 Frank Waldman, “Dodger Plan for Chavez Draws Fire,” Los Angeles Times, October 22, 1959: A1.

15 Frank Waldman, “Council Votes Chavez Ravine Zone Changes,” Los Angeles Times, November 6, 1959: A1. A few days later, New York Times sports columnist Arthur Daley would portray this as the council caving in as O’Malley cried wolf. He noted the team’s attendance and asked, “O’Malley walk out on such a windfall? He ain’t that crazy.” Daley, evidently unfamiliar with the continuing battle, didn’t recognize that the 9-to-5 vote in favor of the zoning changes reflected the consistent split on Dodger issues during that time period. Nobody’s mind had been changed either by the opponents’ or O’Malley’s rhetoric. Arthur Daley, “Sports of the Times: Sounding the Lupine Alarm,” New York Times, November 11, 1959: 47.

16 “Sit-down Strike in Ruins Begun by Chavez Evictees,” Los Angeles Times, May 10, 1959: B1.

17 “Arnebergh Explains Background of Eviction,” Los Angeles Times, May 9, 1959: 3. See also Eric Nusbaum, Stealing Home: Los Angeles, the Dodgers, and the Lives Caught in Between (New York: Public Affairs, 2021).

18 Sullivan, The Dodgers Move West, 175.

19 “Dodgers Near Finish of Chavez Purchases,” Los Angeles Times, February 12, 1960: 2; “Dodgers Put 3 Chavez Properties in Escrow,” Los Angeles Times, February 13, 1960: B1; Final Eight Homes Sold to Dodgers,” Los Angeles Times, February 19, 1960: B1.

20 Paul Zimmerman, “Hope Vanishes for Dodgers to Be in Chavez Ravine by 1961,” Los Angeles Times, April 26, 1960: C1.

21 Andy McCue, Mover and Shaker: Walter O’Malley, the Dodgers and Baseball’s Westward Expansion (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014), 252-3.

22 “Final Steps Taken on Dodger Baseball Park,” Los Angeles Times, December 23, 1960: B1.

23 McCue, Mover and Shaker, 253.

24 Fresco Thompson with Cy Rice, Every Diamond Doesn’t Sparkle (New York: David McKay Co., 1964), 197.

25 McClellan, “McClellan Tells Full Truth …”

26 Bob Oates, “It’s Goat Hill, Not Chavez Ravine – O’Malley,” Los Angeles Times, February 18, 1969: D1.