The Sultan of Swag: Babe Ruth as a Financial Investment

This article was written by Michael Haupert

This article was published in Fall 2015 Baseball Research Journal

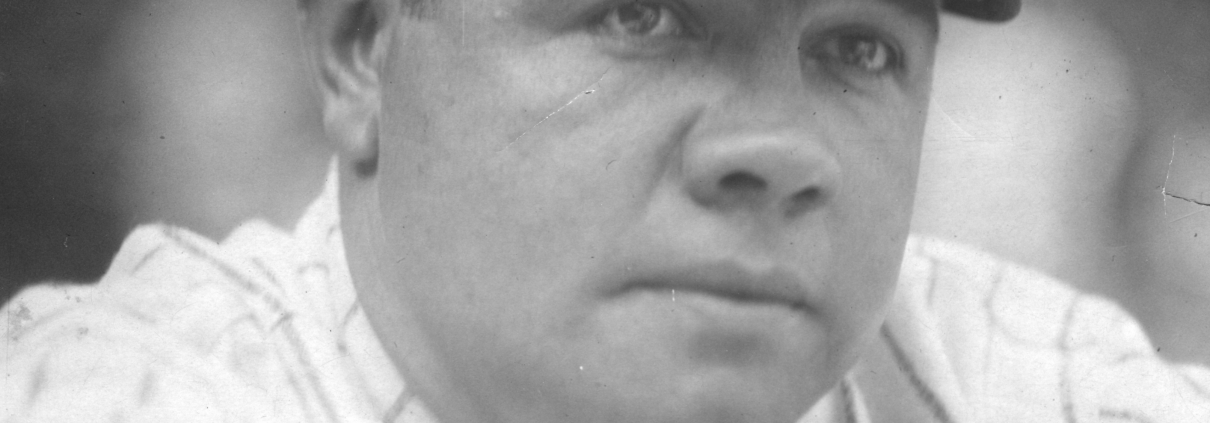

In Babe Ruth’s first year with the Yankees in 1920, he hit 54 homers to break his own American League record set the year before with Boston. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

On the morning of January 6, 1920, New Yorkers awoke to a headline in The New York Times that screamed “Ruth bought by New York Americans for $125,000, highest price in baseball annals.”2 It was dramatic, albeit incorrect (the actual price was $100,000). Secondary headlines correctly predicted that Ruth would be getting a new contract, and reported that Yankees skipper Miller Huggins was already en route to California to ink the slugger to a “large salary.” The Times correctly reported that Ruth had two years remaining on a three-year contract calling for $10,000 per annum, but Ruth, reacting to the sale, had promised that he would not play for that amount, hence the urgent trip by Huggins.3 The Times gushed that “Ruth was such a sensation last season that he supplanted the great Ty Cobb as baseball’s greatest attraction,” and in obtaining the services of Ruth for next season “the New York club made a ten strike which will be received with the greatest enthusiasm by Manhattan baseball fans.”4 They went on to report that the Yankees were prepared to offer Ruth a contract of $20,000 per year, twice what he was being paid by Boston. He would prove to be worth every penny of that contract…and far more.

Curiously, the Boston and New York papers did not necessarily react in the way one might expect. The day after the purchase was announced, the Times decried the Ruth sale, complaining that “it marks another long step toward the concentration of baseball playing talent in the largest cities, which can afford to pay the highest prices for it. That is a bad thing for the game; and it is still worse to give a valuable player stranded with a weak club the idea that if he holds out for an imposing salary he can get somebody in New York or Chicago to buy his services.”5

The Boston Herald, on the other hand, urged fans to be patient and wait to see how the trade worked out. Boston had a history of selling stars, having previously parted with Cy Young and Tris Speaker, and still had five World Series titles to show for it, including three of the previous four.

The Boston Post was less optimistic, arguing that Ruth was special. “He is of a class of ball players that flashes across the firmament once in a great while and who alone bring crowds to the park, whether the team is winning or losing.”6

No less a sage than the venerable Connie Mack thought it was a good thing for baseball. “Ruth will be a more valuable man to the Yankees than he would have been to the Red Sox. As a matter of fact, New York needed him more than Boston.”7 While this is now widely recognized by economists as being true from a financial perspective, at the time Mack was focused more on the impact on the field. He felt Ruth was more valuable to the Yankees than the Red Sox because the latter was well fortified with outfielders and was a well-balanced club despite the loss of Ruth.

History would prove Mack wrong. While the Red Sox actually improved the first two years after selling Ruth, rising from a 66-win sixth-place finish in 1919 to fifth place with 72 wins in 1920 and 75 wins (good for another fifth-place finish) in 1921, that would be their high water mark for the next 13 years. After the sale of Ruth, the Red Sox would suffer through 14 consecutive losing seasons, never rising above the second division, and finishing dead last six consecutive seasons (1925–30) and eight times in a nine-year span. The Yankees, on the other hand, won seven pennants and four World Series with the Babe, and suffered through only one losing season in the 15 he was on their roster, finishing lower than third place only once. Not only did Ruth lead the Yankees to success in the standings, but he would prove to be a box office draw in his own right.

The press recognized this potential. The day after the sale was announced the Times predicted that “with Babe Ruth on the club the Yankees will become a strong attraction in Florida.”8 As if to prove the prognostication correct, a headline the next day announced that the city of Jacksonville, Florida planned to advertise the Yankees’ spring trip there “like a circus” in order to reap the benefits of the expected interest Ruth would generate. The Jacksonville Tourist and Convention bureau announced they were implementing an extensive advertising campaign to bring visitors to the city during the time the Yankees were there playing the Dodgers. The city announced they would upgrade West Side Park, where the Yankees practiced, and Sally League Park, spring home of the Dodgers. The Rotary Club of Jacksonville announced they would also help with the campaign to boost the visit of the ball clubs, and the city of Jacksonville would enjoy several holidays during the training session.9

The New York Times recognized the value of Ruth “as the super attraction in all baseball.” They correctly predicted that his popularity and impact on the team would make him “the game’s greatest drawing card, his power in this respect enhanced through that record deal, performing in the largest city of the major leagues. It will not be surprising if the Yankees of 1920 set new records for home attendance in a season, likewise for attendance on the road.” Ruth not only “brings in dollars at the gate but he helps to make the team a pennant contender, which further adds to the worth of his presence on the club…[he] would have been a “good buy” at a figure higher than the sum disbursed. He should pay for himself in a few years at best.”10 Indeed, despite commanding the highest salary in MLB for 13 of his 15 years in pinstripes, Ruth turned out to be arguably the most profitable investment the Yankees ever made.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE YANKEES

The New York Yankees, the most storied franchise in Major League Baseball history, had an inauspicious beginning. The team was moved from Baltimore in 1903 as the American League sought to establish a foothold in New York. The franchise was sold to two local owners, William Devery and Frank Farrell, who were able to accomplish something that American League President Ban Johnson had been attempting to do for two years: secure enough land in Manhattan to construct a ballpark. The rival leagues went beyond mere refusal to cooperate: they resorted to out and out war. Andrew Freedman, owner of the National League New York franchise, was a Tammany Hall insider, and he used his political connections to keep the American League at bay by preventing them from securing the necessary land to construct a stadium in which to house a team.

However, when Tammany power lapsed, Farrell and Devery were aligned with the new powers. Johnson took advantage of this connection when he sought out the pair to purchase the Baltimore team and transfer it to Manhattan.11 Their first order of business was to build a ballpark on acreage on Washington Heights overlooking the New Jersey palisades. The press dubbed the franchise with several nicknames referencing the location of their stadium, including “Hilltoppers” and “Highlanders.”

Devery and Farrell sold the franchise after the 1914 season for $460,000.12 The new owners of the Yankees were a pair of well-heeled local businessmen—Colonel Tillinghast L’Hommedieu Huston and Colonel Jacob Ruppert. Equally as important as their wealth was their business acumen. Ruppert had been raised in the brewery business, and Huston was a successful engineer. Both men had an interest in baseball, and more importantly, knew how to make money, recognizing that investing in a quality product might mean short term losses in order to procure long term gains.

The Yankees had been playing in the shadow of the Giants since their arrival in town. Now that men with sufficient funds owned the team, the Yankees made the necessary moves toward profitability. They began by improving the playing talent, resulting in a more competitive team, which in turn generated greater fan interest and gate revenue. After the colonels bought the team, they improved in the standings from sixth place in 1914 to consecutive third place finishes in 1919 and 1920, followed by three straight trips to the World Series.

Jacob Ruppert, Miller Huggins, Ed Barrow: Yankees front office made the deal of the century by acquiring Ruth in January 1920. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

THE RUTH PURCHASE

The Yankees were not an instant success either on or off the field. It wasn’t until the 1920s that the team consistently began to win and generate profits. Not coincidentally, it was 1920 when Babe Ruth first appeared in their lineup.

The most famous and financially successful move the Yankees made was the purchase of Babe Ruth. He contributed to a Yankee powerhouse that appeared in six World Series in the decade following his arrival in town and attracted so many patrons that the Yankees constructed a monument called Yankee Stadium to house them.13

Ruth cost the Yankees $100,000 in January of 1920. Baseball lore claims that the Boston Red Sox, owned by Broadway magnate Harry Frazee, sold Ruth because Frazee was strapped for cash after the dismal failure of one of his shows. The legend further adds that the sale price of Ruth was only part of the purchase agreement. In addition, the Yankees allegedly loaned Frazee in excess of $300,000 to shore up his theaters or pay the former owners of the Red Sox. No evidence exists in the Yankees’ account books that such a loan took place. The $100,000 purchase price (erroneously reported as $125,000 in newspapers at the time) is well documented. It took the form of $25,000 in cash plus three $25,000 promissory notes due on November 1 of 1920, 1921, and 1922. The interest rate was 6 percent, for a total cost, including interest, of $108,750.14

The matter of the loan is hard to analyze without any evidence. While it is possible the loan took place, depending on its terms it may have had no relation to the Ruth purchase. The decision to loan money to Harry Frazee appears to be a separate financial decision. The only way in which it would have an impact on the value of the Ruth purchase was if the terms of the loan were better than the market rate. For example, if a condition of the sale of Ruth to the Yankees was that Jacob Ruppert loan Harry Frazee $300,000 at zero interest over a period of ten years, then the true cost of Ruth increases by the amount of interest that Ruppert would have collected on the $300,000.

There are a couple of problems with this scenario, however. First, it is apparent from examining the Yankees’ account books that the loan, if it was ever made, was not made by the Yankees. It could only have been made by Ruppert or Huston privately. Since Ruppert was the primary negotiator in the Ruth deal, it stands to reason that if any loan was made, it would have been from Ruppert.

If the loan was made by Ruppert, then it seems unlikely that he would have made it at below market rates. The deal to secure Ruth provided revenues to the Yankees, of which Ruppert was only a fifty-percent owner. In addition, it seems even less likely that he would make such a financial arrangement given the strained relationship that existed at the time between Ruppert and Huston. The rift between the two men would eventually grow to the point where Ruppert bought out Huston in 1923, becoming sole owner of the franchise for the remainder of his life.

If a loan was made from Ruppert to Frazee as a condition of the Ruth sale, but the loan was at the market rate of interest, then it had no bearing on the value of the Ruth deal. The decision by Ruppert to loan Frazee money would have been made on the same basis that Ruppert would make any other decision regarding his personal finances: what would earn him the best return given his current financial situation?

Until such time as evidence regarding the details of the alleged loan surfaces, we cannot make a complete analysis. However, it seems reasonable to assume that the cost to the Yankees of Babe Ruth was the purchase price of $100,000 plus interest, and no more. This analysis of the return to the Yankees on the purchase of Ruth will proceed along these lines.

The purchase of Ruth returned immediate dividends for the Yankees. Yankees home attendance more than doubled from 619,000 in 1919 to almost 1.3 million in 1920. As a result, home receipts more than doubled each of the next three years. The team appeared in the World Series in 1921, 1922, and 1923, earning an additional $150,000 in revenues, and the Yankees’ share of road receipts more than doubled in Ruth’s first three seasons in New York. While attendance did increase around the league during the decade following World War I, the Yankees were an outstanding outlier. From 1920 through Ruth’s final season with the Yankees in 1934, the Yankees failed to lead the league in attendance only twice. The first instance was 1925 when Ruth played in only 98 games due to injuries and suspensions. This was the fewest number of games he would play as a Yankee. In 1934 the Yankees also failed to lead the league in attendance during Ruth’s final season in New York. Prior to Ruth’s arrival the Highlanders/Yankees had finished in the top five of MLB attendance only three times, peaking at third in 1918. After the arrival of Ruth they led the league in attendance during 13 of his 15 years with the team. After his departure the Yankees led the league only three times in the next six years.

Was $100,000 an unusual amount of money to spend for one player? Certainly it was an enormous sum, but it was not as breathtaking as it may at first seem. The purchase and sale of ballplayers was more frequent in those days than it is today. Selling players was a very common way for an owner to make ends meet when finances got tough. On more than one occasion Connie Mack settled his bills by dismantling a World Series championship team by peddling his players for cash. Mack was not the only owner to follow this path to success. In fact, the Red Sox were on the buying side of this very formula when they won the World Series in 1918. So when the Red Sox sold Ruth, the sale itself was not unusual. Even selling a future Hall of Fame player was not unusual. As mentioned earlier, the Red Sox had previously sold Cy Young and Tris Speaker. What made this sale unique was the enormous impact that Ruth had on the Yankees, both on the field and at the box office.

By way of comparison, consider another young left-hander who was sold to New York by Boston in 1919 for the princely sum of $55,000. He subsequently led New York to pennants and World Series victories. That lefty was pitcher Art Nehf, and the teams were the Braves and the Giants.15 Nehf led the National League in complete games in 1918 with 28 and won a total of 32 games in 1917 and 1918. In 1919 he won 17 games, splitting his time between the Braves and the Giants. He averaged 20 wins for the next three seasons as the Giants won two pennants and two World Series. Art Nehf was a good investment at $55,000. While Ruth cost nearly twice as much, he was an everyday player coming off a home-run record-setting season. The price may have been a stretch at the time, but it was not preposterous.16

ANALYZING THE FINANCIAL RETURN

In analyzing a financial return for Babe Ruth, we must consider the original investment (the purchase price of $100,000), the change in revenue resulting from the investment (more about this later), and the additional costs (interest on the promissory notes and salary and bonuses paid to Ruth). The return on that investment is calculated as the additional revenue Ruth generated less the additional costs to the Yankees due to Ruth as an annual percentage of the $100,000 purchase price. This is a standard return on investment calculation.

Interestingly, Ruth cost the Yankees less than his $20,000 salary and signing bonus during his first two years. According to the Yankees’ ledgers, the Red Sox paid part of Babe Ruth’s salary in 1920 and 1921. When they purchased Ruth from the Red Sox, the Yankees inherited the remaining two years of Ruth’s three-year, $10,000 per year contract. Fearing that Ruth might threaten to hold out, the Yankees negotiated with the Red Sox to have the Sox pay half of any salary increase or bonus the Yankees offered to Ruth for the duration of the two years of his contract, up to $5000 per year. Indeed, the Yankees and Ruth agreed to raise his salary to $15,000 per year for the remaining two years on his Red Sox contract, plus a bonus of $5000 each year. As a result the Yankees only had to pay $15,000 per year through 1921, while the Red Sox had to pay the remaining $5000 of his contract each of those years. The Red Sox are the first documented example of a team paying the salary of a player they had sold or traded to another team. Such arrangements are commonplace today, in an era of salary-dumping trades, but in 1920 the environment was quite different, making this arrangement ground-breaking.17

The Yankees were not always that savvy about making deals however. They did let Ruth talk them into a contract clause for 1921 which paid him $50 per home run: the same year Babe shattered the record by blasting 59. The $2,950 the Yankees paid him that year was just a hair less than twenty percent of his salary. It was the largest performance bonus the Yankees would pay for more than a quarter of a century, and the last time Ruth ever had a performance clause in his Yankees contract.

CALCULATING REVENUES GENERATED BY RUTH

A player’s value to a team is measured by his impact on team revenues. In Ruth’s day, this was primarily done through his impact on attendance. Economic research shows that the most important thing a team can control that will affect its attendance is the quality of the team, measured by winning percentage. The population of the city and its income level are also important determinants of attendance, but a team can’t alter those variables. Putting a better team on the field, however, is well within the control of the team. Research also shows that a better player will contribute more to his team’s ability to win, thereby contributing more to the total revenue of the team.18 This concept is known in the economics literature as marginal revenue. A baseball player’s marginal revenue is the additional revenue that a team earns as a result of the player being on the team.

There is a second way that a player can impact team revenues, and that is through what we call the “superstar” effect.19 Some players are so popular that fans will go out to see them just because they are in the game, regardless of how good their team actually is. LeBron James is a good example of this. When his team is on the road, games sell out, even when he visits poor teams that have plenty of empty seats for every other game. Babe Ruth may not have been the first baseball superstar, but he was arguably the trendsetter when it came to selling tickets. While there are models to estimate the superstar impact of players, I do not attempt to do so in this article because of a scarcity of necessary data.

I use Wins Above Replacement (WAR) to calculate Ruth’s impact on the Yankees winning percentage.20 WAR is a measure of the number of games a player is responsible for his team winning above a replacement player. For example, in 1929 Babe Ruth had a WAR of 8.0, meaning that the Yankees would have won eight fewer games if Ruth was removed from the roster and a typical replacement player was added in his place.

Calculating a player’s marginal revenue using WAR is a simple two-step process. First, regress ticket revenue on a series of variables, including team winning percentage.21 Then, using a player’s WAR, determine how many games the team would win without him. In the preceding case of Ruth in 1929, his WAR was 8.0, meaning that with an average replacement player in the lineup instead of Ruth, the Yankees would have won eight fewer games, thus their winning percentage would have been .519 instead of .571, a difference of .052. Multiplying this by the coefficient on winning percentage in the regression yields the marginal revenue of Babe Ruth to the New York Yankees in 1929. This actually underestimates Ruth’s contribution to the bottom line, because it assumes that his impact on the team revenues came only through his impact on the quality of the team, and not at all because of the superstar effect. Given Ruth’s talents, fame, and celebrity, his superstar impact was undoubtedly quite significant.

Team revenue in Ruth’s day was simpler to calculate than it is in the twenty-first century because there was no television revenue, and there was little if any radio revenue. However, there are still some tricky revenue sources to consider. After calculating the impact of a player on the winning percentage of his team, and the ticket revenue value of that additional winning percentage, we must then calculate his impact on other important (though far smaller) sources of revenue. In addition to winning percentage, concession revenue, revenues from road games, World Series revenues (important for the Yankees, who appeared in half the World’s Series played during Ruth’s tenure with the club), and exhibition game receipts, which became increasingly important after Ruth joined the team, are analyzed. The impact on the concession, road and exhibition game revenues is calculated by looking at the ratio of each to home revenues and taking a straight percentage impact. The idea here is that Ruth did not necessarily change the ratio of concessions to home attendance, but the increase in home attendance increased concession revenues by the same relative amount.

Table 1: Babe Ruth impact on Yankee revenues

(Click image to enlarge)

Table 2: Babe Ruth earnings in perspective

(Click image to enlarge)

Table 3: Yankee earnings on Ruth compared to alternative investments

(Click images to enlarge.)

A quick glance at Tables 1 and 3 reveals that the financial return earned by the Yankees on the purchase of Babe Ruth was nothing less than spectacular. And Table 2 reveals that despite his status as the highest paid player in the game, the Yankees were exploiting Ruth’s ability to draw crowds and generate profits. This is demonstrated by looking at the ratio of Ruth’s salary to his marginal revenue. Economic theory predicts that in a competitive market a player will be paid his marginal revenue. Baseball in the 1920s was hardly a competitive labor market. With the reserve clause in place Ruth never had a chance to sell his skills on the open market like modern free agents do. Because of the reserve clause, the Yankees were able to keep his services while only paying him a fraction of his marginal revenue. And while Ruth was being paid only a fraction of his marginal revenue, he was being paid a considerable amount more than the average American worker in his day. Keep in mind that this is a conservative estimate of the financial impact of Ruth on the Yankees. No attempt has been made to estimate the superstar effect of Ruth.

Perhaps no better anecdotal evidence for the importance of Babe Ruth to the Yankees can be provided than the 1925 season, the worst in Ruth’s career. He played in only 98 games that season, batting .290—52 points below his career average—and hit only 25 home runs, his lowest output since before he became a full-time player in 1919, and a depth to which he would not sink again until 1934, his final year in a Yankees uniform.

The impact of his absence from the lineup was felt by the Yankees on the field and in the pocketbook. On the field, the Yankees collapsed from an 89-win season and second-place finish in 1924 to seventh place and 69 wins in 1925. It was the only year that the Yankees had a losing record in Ruth’s tenure with the team. At the box office, the absence of Ruth and the poor performance of the team was just as evident. The Yankees attendance fell 33 percent to under 700,000, the first time they failed to draw over a million fans since the arrival of Ruth and the only time except his final season with the team they would not lead the league in attendance. Overall revenue in 1925 was off 25% from the year before, dropping the Yankees below the league average in profits for the only time during the decade.22

RUTH AS A FINANCIAL INVESTMENT

So how good a financial investment was Babe Ruth? Table 1 details Ruth’s contribution to various Yankees revenue sources. Note that Ruth’s actual compensation in most years differed from his contracted salary (Table 2). The presence of frequent bonus clauses was the primary reason for this difference, but a regular series of fines levied on the Babe by the Yankee brass accounted for several instances in which Ruth actually earned less than his contract stipulated. The years from 1924–26 were particularly tough for the Babe, especially 1925, when he received nearly $10,000 less than his contracted $52,000 salary. A contributing factor to Ruth’s sizeable fines during that three year period was the appearance of a temperance clause in his contract. From 1922 through 1926 Ruth’s contract prohibited him from drinking or staying out late during the baseball season at the risk of an unspecified financial penalty. Even a cursory look at any of the Ruth biographies suggests that he ignored this clause with regular abandon.

More often than not, however, Ruth earned more than his contracted salary due to the frequent bonuses and World Series shares he earned. Sometimes Ruth was paid a signing bonus, and several times he received a bonus in the form of a percentage of the gate for his participation in exhibition games. As noted earlier, in 1921 he had a performance bonus clause in his contract, which proved quite lucrative for the Babe.

Ruth was the major draw for Yankees exhibition games, and in order to maximize the benefit of that attraction, the Yankees gave Ruth great incentive to participate in them. By the end of his career, though he was past his prime as a player, he was still a major gate attraction and the Yankees paid him 25 percent of the net proceeds from exhibition games in which he played. During the Ruth era, the team’s revenues from exhibition games exploded. Prior to 1920, the most the Yankees ever made from exhibition games was $3,800 in 1916. From 1920–34 they never earned less than $12,000, and seven times took in $20,000 or more, topping $35,000 in 1921.23

Ruth’s highest earning year for the Yankees was 1930 when he netted more than $84,000 in salary and exhibition game receipts. Relative to his salary however, Ruth’s biggest year was 1921 when he earned more than 250 percent of his $15,000 salary through a combination of a signing bonus, a home-run bonus, and receipts from exhibition games. And yet, that year he earned less than 18 percent of the revenue he generated for the Yankees. 1921 was a pretty good year for Ruth—and by extension, the Yankees. His performance that year is still the all-time high for extra base hits and total bases, and it ranks in the top five all-time for runs scored, slugging, offensive WAR, runs created, and OPS as well. He hit an amazing 12 percent of the total home runs in the league, personally out-homering five other teams. Besides home runs, he also led the league in on base percentage, slugging, OPS, runs scored, total bases, RBIs, walks and runs created. He firmly established himself as the undisputed gate attraction in the game and a goldmine for the Yankees.

PROFITING FROM THE BABE

The net profits to the Yankees from their investment in Ruth are found in Table 3. The Yankees profited from the presence of Ruth on the roster in every year, though they barely covered his salary in 1925. They more than made up for this in other years however, earning more than $100,000 in net profit on Ruth on six separate occasions. Babe was a colossal money-maker for the Yankees. During his career, they earned more than one million dollars (not adjusted for inflation) in profit on Ruth.

Over the course of his career, the total return earned by the Yankees on their investment in Babe Ruth was 1254 percent. Because of its volatility, the stock market returned a net gain of only 17 percent during the period. Bonds did much better at 205 percent, but still fell far short of Ruth. It turns out that Babe Ruth was indeed a wise investment for the Yankees. It would have been difficult for Jacob Ruppert to find any other investment that could have done nearly as well.

Despite the riches the Yankees were earning from Ruth, Yankees general manager Ed Barrow wasn’t particularly appreciative of the Babe in the waning years of his career. In a letter addressed to sportswriter F.C. Lane in March of 1933, Barrow complained that Ruth “is greatly overpaid.” Adding that he hoped “the Colonel will stand pat on his offer of $50,000 and call the big fellow’s bluff about retiring.”24 The Colonel did not stand pat, eventually offering Ruth $52,000 plus 25 percent of the net receipts from exhibition games, though ultimately only paying him $42,000. It was not one of the Babe’s better years, though he did return a nice profit of about $45,000 for the Colonel’s investment. This was certainly better than Ruppert could have done by investing in the stock market, which lost 17 percent that year. The 45 percent return also outperformed the bond market that year by a substantial amount.

The return on Ruth fell the next year, his final season in New York, to its second lowest, returning the team just over $32,000 in net profits. This was at a much reduced salary of $35,000, however. The Yankees, because they were able to reduce Ruth’s salary toward the end of his career, were able to ride him for a couple of final years of profitable employment before finally shipping him off.

When he was ingloriously dispatched to the Braves in time for the 1935 season the Yankees received nothing in return. Their records indicate that he was sold to the Braves without monetary consideration. It was indeed a quiet ending to the most famous financial investment in Yankees history.

MICHAEL HAUPERT is Professor of Economics at the University of Wisconsin–La Crosse. He is an avid baseball fan and appreciates the ability to combine his hobby with his work. He has published on the economics of baseball in several academic journals, including “NINE,” “Cliometrica,” “Black Ball,” and “Base Ball.” He is currently working on a labor history of professional baseball.

Notes

1. Thanks to Ken Winter, who was my coauthor on much of the background research for this paper, and Clifford Blau for his careful fact checking. Thank you also to two anonymous referees whose careful reading and valuable comments helped to improve this article. Any remaining errors or oversights are strictly the fault of the author.

2. The New York Times, January 6, 1920, 16.

3. While the thought of retiring might strain credibility, Ruth was, in fact, in Hollywood at the time the sale was announced, making Headin’ Home, which would be released later that year by Kessell & Bauman, indicating his attraction beyond the ballfield. In fact, over the length of his career, Ruth made substantial amounts of money outside of the game, appearing on vaudeville, in movies, endorsing products, and making public appearances.

5. The New York Times, January 7, 1920, 18.

6. The New York Times, January 7, 1920, 22.

8. The New York Times, January 8, 1920, 18.

9. The New York Times, January 9, 1920, 18.

10.The New York Times, January 12, 1920, 11.

11.According to Rodney Fort (http://www.rodneyfort.com/SportsData/ BizFrame.htm) Frank Farrell purchased a 75% share of the Baltimore franchise in 1903 for $180,000. That translates into a market value of $240,000 for the team. The franchise was relocated to New York for the 1903 season and ultimately became known as the Yankees.

12.Michael Haupert and Kenneth Winter, “Pay Ball: Estimating the Profitability of the New York Yankees 1915–1937,” Essays in Economic and Business History, vol XXI, 2003, 89102.

13.Yankee Stadium opened in 1923. Prior to that the Yankees played in their own stadium, American League Park, from 1903–12. From 1913 through 1922 they shared the Polo Grounds with the Giants.

14.New York Yankees Financial Ledgers. National Baseball Library, Cooperstown, New York.

15.The deal also brought four players to the Braves according to Baseball-Reference.com.

16.Kenneth Winter and Mike Haupert “Yankee Profits and Promise: The Purchase of Babe Ruth and the Building of Yankee Stadium,” in Wm. Simons, ed., The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2003, 197–214.

17.New York Yankees Financial Ledgers. National Baseball Library, Cooperstown, New York.

18.The seminal work on this topic was done by Gerald Scully, “Pay and Performance in Major League Baseball,” The American Economic Review, 64, no. 6 (December 1974), 915–30.

19.David J. Berri, Martin B. Schmidt and Stacey L. Brook, “Stars at the Gate: The Impact of Star power on NBA Gate Revenues,” Journal of Sports Economics 5:1 (February 2004), 33–50.

20.WAR values are from Baseball-Reference.com, accessed during the spring of 2015.

21.I regressed attendance x average ticket price on winning percentage, winning percentage in the previous year, games behind (or ahead) in previous year, World Series appearance in previous year, age of team, and gross domestic product (GDP). The regression covered the New York Yankees from 1903–42 (years for which I had sufficient financial data). Only winning percentage, previous year winning percentage, and GDP were significant.

22.Emanuel Celler, Hearings of the Monopoly Subcommittee of the House Judiciary Committee, 1951.

23.New York Yankees Financial Ledgers. National Baseball Library, Cooperstown, New York.

24.Letter from Edward Barrow to F.C. Lane, March, 1933, F.C. Lane papers, BA MSS 36, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York.