The Third Brother Dean: “Elmer the Great”

This article was written by Paul Geisler Jr.

This article was published in Fall 2014 Baseball Research Journal

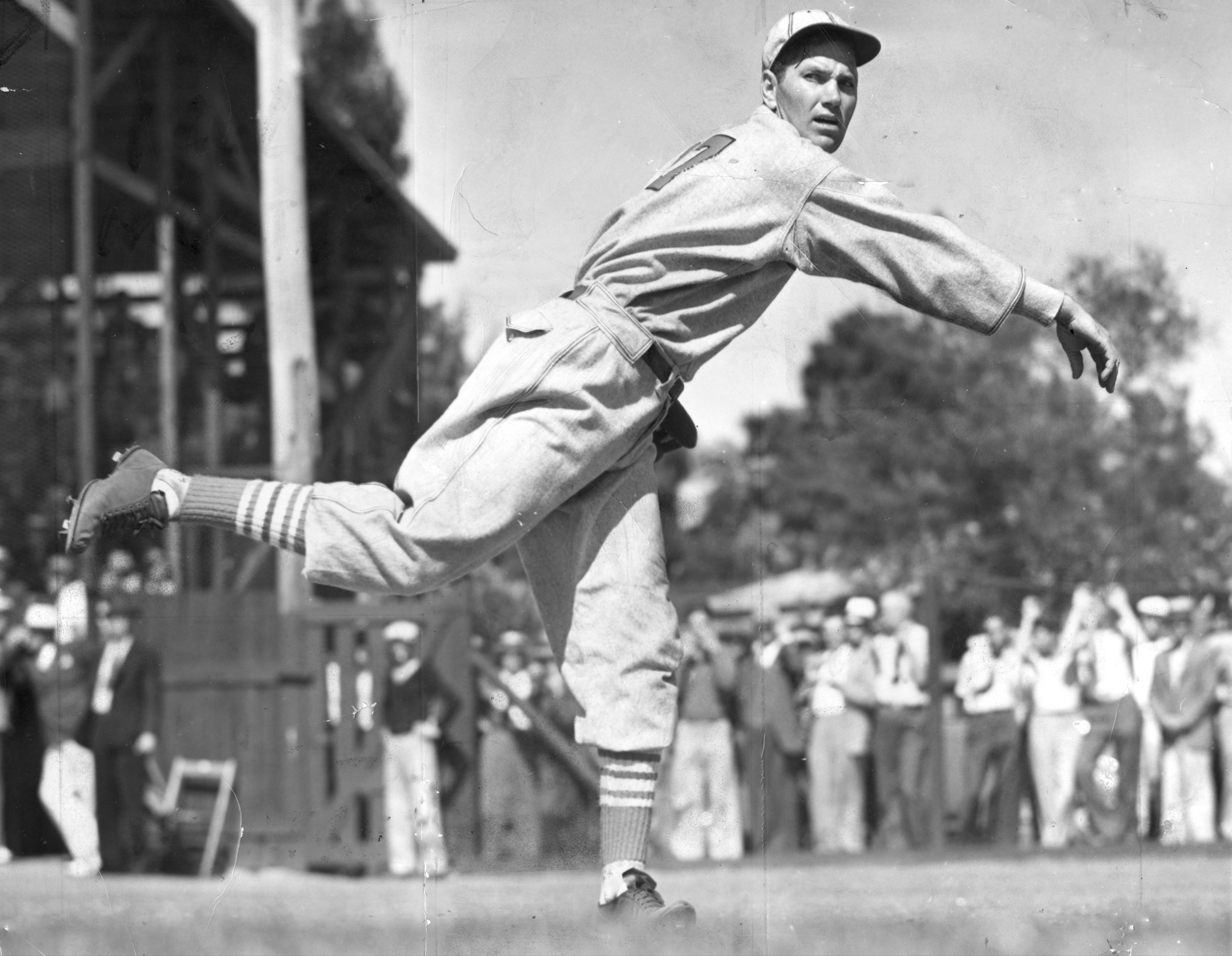

Elmer Dean, center, the older brother of St. Louis Cardinals stars Dizzy and Paul Dean shows his new House of David teammates how he grips a curveball on May 5, 1935. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

The brothers Jay Hanna (“Dizzy,” also known as Jerome Herman) Dean and Paul Dee (“Daffy”) Dean are remembered as perhaps the greatest brother pitching duo ever. Combining to win 49 games for the 1934 St. Louis Cardinals, they won all four Cardinals’ wins in the seven-game World Series. Well, meet their older brother Elmer Monroe Dean, “Elmer the Great,” “long recognized as the ace goober salesman of the Texas League” and “almost as celebrated in his line as his younger brothers are as pitchers.”1

Born in 1909 to sharecroppers Albert and Alma Dean in rural Arkansas, Elmer spent most of his childhood picking cotton and playing baseball with his younger brothers.2 Both parents had athletic backgrounds. “Ab” played third base on a semipro nine, and Alma batted lead-off for her softball team. The family worked as share-croppers and moved often, following the crops. In all they had five children, but the first two died early. Jay and Paul followed Elmer, in 1910 and 1912, respectively.

Alma died of a severe case of tuberculosis in 1917, leaving Ab and the boys to work the fields together. Dizzy later remembered, “I never knew anyone who had it as tough as my father did.”3 They stayed in shacks and lived off the land, eating “plain grub,” as Ab called it—”sowbelly and cornmeal when there was a little money; sweet potatoes and peanuts when there wasn’t.”4

The boys played ball, usually barefoot, wherever they could find an open spot, with a potato sack for home plate, a rock wound with string for a ball, and whatever kind of stick they could find for a bat. Elmer usually caught his brothers’ pitches, or shagged flies in the outfield. Sometimes they played pick-up games for money, with the stakes reaching 50 cents or a dollar, equivalent to a day’s wages.5 Elsie Brennen Wachtel, who grew up on a farm neighboring the farm where the Deans worked, remembers Dizzy had a rhyme for the boys: “Poodle, Jay, and Paul—and that’s all.”6

Sometime in 1927 Elmer got separated from the rest of the family. They had traveled to Texas to visit Dizzy, who had just enlisted in the Army with a falsified birth certificate. Elmer’s vehicle moved on, while Pa and Paul found themselves stuck waiting for a long freight train. They drove around for a while, but found no sign of Elmer. Pa had no way to contact him, with no settled residence or telephone. Mentally challenged from birth, Elmer had never learned to read or write. But Pa did not seem very worried and never notified the police. “He’ll turn up someday,” he said confidently.7

About four years later, Elmer, now working on a farm in Arkansas, noticed a newspaper picture of Dizzy pitching for Houston in the Dixie Series of 1931. “That’s my brother!” shouted Elmer. Others in the drugstore with Elmer read him the story, and the druggist sent a letter to Dizzy, who by then was barnstorming through small towns in Missouri and Arkansas with brother Paul. Paul and Dizzy went to reclaim their older brother. “We liked to never get Elmer to go,” remembered Paul. They packed him in their car with his possessions stuffed in a pasteboard suitcase. Paul drove, and Dizzy sat with Elmer in the back. “Diz just took that suitcase and throwed it out the back of the car,” continued Paul.

“‘Hellfire, Jay, them was my clothes. Them was all the clothes I got,’” responded Elmer. Dizzy promptly stopped in town and outfitted Elmer with a new wardrobe.8

Albert had moved to the Houston area, with Dizzy playing for the Buffaloes in 1931, as Paul moved from Springfield, through Houston, and eventually to Columbus that year. Elmer had played some in the Ozark League, and now saw his chance to join the Buffaloes himself.

Houston team president Fred Ankenman had high hopes of finding a third Dean brother, who might keep up the Dean tradition. Elmer signed on in 1933, at least for a tryout, as a six-foot, 185-pound outfielder who batted left-handed and threw right-handed. In anticipation, Ankenman commented, “if you thought Dizzy was dizzy, and if you can imagine his brother Paul was strange, you ain’t seen nothing yet.”9

Elmer’s semipro experience in Arkansas was described as “extremely semi.” He did not impress the Houston brass. He appeared “far from a gazelle on his feet and not too handy at catching and throwing,” and they rated his batting as not “up to the standard required of outfielders.” Manager Casey Selph worked long and hard to make Elmer a pitcher.10 Though Elmer remained unimpressive, with the Dean name “such a good drawing card he probably will be retained until the squad is cut to 16.”11

Though he called himself “a right smart country ball player,” Elmer did not seem to fit anywhere.12 The team did not issue him a uniform and left him behind when they traveled to Galveston for their opening series. Because he “promised to furnish so much entertainment for the fans,” Ankenman offered him a job as bat boy. Elmer protested, and threatened to quit.13

“Batboy!” exclaimed Elmer. “Me, who taught my kid brother Dizzy how to pitch.”14

Still hoping to keep a Dean in Houston, Ankenman then offered Elmer a job selling concessions. “This new field is wide open for a man with Elmer’s singularity of aim and capacity of voice.”15 Elmer found early success, then his sales started to drop. Ankenman watched him one day and discovered that after removing the caps, Elmer would wipe the soda bottles with the same towel he used to wipe sweat from his face. The boss quickly shifted Elmer to selling peanuts and he soon became a star attraction at Buff Stadium.16

Elmer quickly gained recognition with his familiar cry, “Get your goobers here, and I’ll tell you how I taught Dizzy Dean to pitch. He’s my brother.”17

After his first season, Elmer had earned the recognition as “probably the baseball fans’ most popular peanut dispenser here [Houston] during the diamond campaign.”18

One of Elmer’s biggest thrills on the field came that fall. Dizzy came to Houston to pitch a benefit barnstorming game, and Elmer hit a triple off his kid brother. “It was the only real wallop off Dizzy, whose team won, 9 to 1.”19 When not shouting at the crowds about his goobers, Elmer liked to roam the tall buildings of the city, “indulging his hobby of riding in elevators.”20 He also supported himself running errands and working in a tire shop, down the street from the bare apartment where he lived with his father.21

The next season, 1934, Paul joined Dizzy with the big league Cardinals. Dizzy lobbied St. Louis general manager Branch Rickey to find Elmer a job, too. Rickey had recently hired his brother as a scout, and Dizzy hoped for a clerical job in the front office for Elmer. The eldest Dean brother stepped off the bus from Houston in St. Louis only to find that his great reputation with the Buffs had earned him a position hawking peanuts in the St. Louis stands. St Louis headlines read, “Cards Buy a Third Dean Pitcher—And it’s a Nutty Idea,” and, “The Dean Brothers—Two Nuts and One Goober.”22

A Dean family meeting, reportedly led by Pat Dean (Dizzy’s wife), determined that “Elmer, hawking peanuts in the grandstand, would put Dizzy and Paul in an undignified light.”23 Saying he did not much care for St. Louis, Elmer soon returned to Houston “much to the delight of peanut-conscious and pop-minded fans at Buffalo Stadium,” without selling one goober in St. Louis.24

Houston fans welcomed Elmer back. News accounts reported “his stentorian cry of ‘ice cold soda water— who wants one?’ has won him the rating of a championship contender in his chosen line.” He wore a hat band clearly labeled “Elmer Dean.”25 According to Roy Forrest of the Miami News, “Nobody could duplicate Elmer’s lusty bellow—‘Buy a goober!’—which sold thousands of pounds of peanuts.”26

Early in the summer of 1934, Dizzy and Paul staged a short strike, seeking an increase in pay. Elmer seemed to take this lead from his brothers, as he went on strike soon after he returned to Houston. “I want more money or I’ll let your goobers go stale,” he told Walter Benson, director of concessions at the Houston park.27 He missed only one day of work, then returned to the grandstands.

Cardinals star Dizzy Dean helped his older brother Elmer get a job as a peanut vendor with the Houston Buffaloes. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

One day in 1934, Casey Stengel, manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers at the time, asked Dizzy if he had any more brothers. Diz replied, “We got another brother named Elmer, and Casey, you ought to grab him. He’s down at Houston, burnin’ up the league.” Stengel actually pursued the tip, until he learned that Elmer was pitching peanuts for the Texas League club.28

When the Cardinals played the Detroit Tigers in the 1934 World Series, Pa Dean traveled to St. Louis for games three, four, and five. Elmer stayed home at Dizzy’s request, and since the Dean family could not afford a radio of their own, he listened to the games at a nearby gas station.29

In 1935, Elmer left his peanut pitching to join promoter Ray Doan and his traveling bearded team, the House of David, as a pitcher. Pa Dean came along also to do promotional work and serve as team secretary. Elmer played a bigger role in Doan’s promotional schemes than he ever did as a pitcher. He took a lot of ridicule, as well. He usually batted leadoff, and pitched the first inning, then would slip down to one end of the bench and huddle in a corner the rest of the game. House of David players regarded him more as a team mascot than as a player. People mocked his name “Elmer” and nicknamed him “Dippy.” He had left the realm of “Elmer the Great.”30

Elmer returned to Houston to start the 1936 season, hoping again for a diamond tryout. Sure that someday he would play in the major leagues, he said he would not go to the Cardinals. “It wouldn’t be fair to the other teams to let all of the Dean brothers pitch for one club.”31 When Ankenman did not leave him a uniform that fit him, he worked out in his street clothes. He explained that if he did not make the team roster, he planned to hold out, following the lead of his younger brothers in St. Louis, for more money for selling soda and peanuts.32 “I could show ole Diz and Paul something about baseball, if you’d give me a chance.” Dizzy and Paul came to terms with the Cardinals, and Elmer returned to his “ace peanut vending.”33

Early in the 1936 season, Elmer expanded his territory north, as he caught on with the Fort Worth Cats, also in the Texas League. He peddled his wares in the “Panther City” whenever the Buffs were on the road, and return to Houston for their home games. The move proved convenient for the Dean family as Pa Dean had moved to Garland, Texas, outside of Dallas, to help work his son Paul’s farm. Even in Fort Worth Elmer’s “persistent selling talk and his shouts and laughter never fail to attract the attention of the customers.”34

Also early in 1936, the House of David dropped Elmer, reportedly because he could not grow an adequate beard.35 Then before the end of the season, Elmer saw his peanut sales come to an end, as the Houston stadium gave him his “unconditional release.”36 Elmer retreated to Paul’s farm and joined his dad farming, still attempting to play some semipro baseball as a pitcher for Dallas-area teams.37

Elmer spent the next twenty years sharing chores on the farm with his dad. Within six months of his father’s death earlier that year, Elmer died September 24, 1956, following a long illness, leaving his brothers Jay (“Dizzy”) and Paul as his only survivors.

The eldest Dean brother, sometimes known as Goober or Poodle or Elmer the Great, made a distinctive impact in baseball, even if not as a player on the field. “The best doggone goober salesman that ever hit Buffalo Stadium” lived his motto as an outfielder: “Be thar when the ball gets thar.”38, 39

PAUL GEISLER JR. grew up in San Antonio, Texas, and has been a Lutheran pastor for over 35 years. He lives in Lake Jackson, Texas, with his wife Susan and their three children: Sarah, Brydon, and Johanna. He loves anything baseball—playing, watching, coaching, researching, and writing.

- Related link: Learn more about Dizzy and Daffy Dean in SABR’s free e-book on the 1934 St. Louis Cardinals

Notes

1 “Elmer Dean to Sell Peanuts for Panters.” Pampa (Texas) Daily News, May 6, 1936, 6.

2 The website findagrave.com lists his birth date as March 11, 1909, while some sources indicate he was born in 1908.

3 John Heidenry, The Gashouse Gang (New York: Public Affairs, 2007), 30.

4 Timothy M. Gay. Satch, Dizzy, and Rapid Robert (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2010), 57.

5 Heidenry, Op cit., 33.

6 Chauncey Durden. “The Sportview.” Richmond (Virginia) Times-Dispatch, May 9, 1952, 33–34.

7 Robert Gregory. Diz (New York: Viking Press, 1992), 36.

8 Ibid. 75–76. Also Gay, op. cit., 63.

9 “Elmer, Another Dean to Carry Family Tradition.” Dallas Morning News, March 13, 1933, 4.

10 “Cvengros Signed by Houston Club.” Dallas Morning News, March 16, 1933, 2.

11 Lloyd Gregory. “Houston Fans Warm Up to Selph and His Buffs.” The Sporting News, April 13, 1933, 3.

12 Henry McLemore. “Today’s Sports Parade.” Amarillo Globe Times, March 27, 1933, 7.

13 “Dean Fails with Houston.” The Sporting News, April 20, 1933, 2.

14 “Dean’s Brother Selling Peanuts in Houston Park.” Baton Rouge State Times, April 30, 1933, 16.

15 Ibid.

16 Vince Staten. Ole Diz (New York: Harper Collins, 1992), quoted in Heidenry, Op cit., 158.

17 Gregory, Op cit., 91.

18 “Elmer Clouts Triple off Dizzy, but Latter Twirls Team to Win,” Dallas Morning News, October 20, 1933.

19 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, October 26, 1933, 2.

20 “Elmer Dean Fails as Major League Peanut Vendor, So He Returns to the Texas League,” Sarasota Herald, August 28, 1934, 5.

21 Heidenry, Op cit., 225.

22 Ibid. 159.

23 “Elmer Dean, Dizzy’s Brother, Is Not to Peddle Peanuts at Sportsman’s Park After All,” Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, August 12, 1934, 5.

24 “Elmer Dean Fails,” Op cit., 5.

25 Ibid.

26 Roy J. Forrest, “Great Elmer Dean Grows Beard, Joins house of David,” Miami News, March 24, 1935.

27 “Elmer Dean, Goober Magnate at Houston Park, On Strike,” Abilene (Texas) Reporter-News, August 26, 1934, 4.

28 J. Roy Stockton, The Gashouse Gang and a Couple of Other Guys (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1945), 31.

29 Heidenry, Op cit., 226.

30 George C. Fossum. “Dippy Dean Not Like Dizzy or Daffy Dean,” Aberdeen (South Dakota) Evening News, June 1, 1935, 5.

31 “Youngest [sic] Dean Will Twirl Here on Friday Night,” Canton (Ohio) Repository, July 10, 1935, 11.

32 “Brief Bits of Gossip.” The Sporting News, March 19, 1936.

33 “Last Holdout of Dean Brothers Is in Houston Fold,” Corsicana (Texas) Daily Sun, March 25, 1936.

34 “Elmer Dean to Sell Peanuts,” Op cit., 6.

35 Eddie Brietz. “Sports Roundup,” Corsicana (Texas) Daily Sun, May 7, 1936, 11.

36 Felix R. McKnight. “Texas League Coffers Gain,” Heraldo de Brownsville (Texas), August 4, 1936, 6.

37 “The Sports Barker,” Paris (Texas) News, May 5, 1957.

38 Forrest, Op cit., 39.

39 “Oldest Dean Has Motto,” Tampa (Florida) Tribune, May 2, 1933, 9.