The Washington Senators in Wartime

This article was written by Richard Moraski

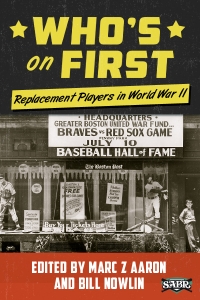

This article was published in Essays from Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II (2015)

Keeping it Alive: The Proactive Clark Griffith

At age 72, Clark Griffith again faced the challenge of maintaining the operations and financial stability of his “small market” team, the Washington Senators, during a world war. The Senators, by population, were the smallest team in major-league baseball. During World War I, the major leagues continued to operate in spite of shortened seasons in 1918 and 1919, reduced attendance, and the loss of 247 players to military service. Griffith also became a very active participant in the selling of Liberty Bonds and other fundraising efforts for the war such as his Bat and Ball Fund, which provided baseball equipment to servicemen.

After the US entered World War II in December of 1941, it didn’t take long for Griffith to become proactive to support the interests of baseball and his team. On December 11, 1941, he initiated the Baseball Equipment Fund, which was built upon the principles of his World War I creation. Upon request of Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, Griffith hand-delivered a letter from the commissioner to President Franklin D. Roosevelt that inquired about FDR’s views on having baseball continue to operate.

Over the years, Griffith developed strong relationships with Washington’s power brokers. He had known Roosevelt for a long time. Building on this relationship, Griffith used all his diplomatic and persuasive skills in discussing the question of keeping baseball up and running during World War II.

Roosevelt sent a letter dated January 15, 1942, to Commissioner Landis that made it clear that in the president’s view it would benefit people if baseball were available for their recreation and to take “their minds off their work even more than before.” The president made it clear that if baseball was played, the players would still be subject to the rules and procedures of the Selective Service draft.

This was known as the “Green Light” letter. It also contained another item that was near and dear to Clark Griffith’s heart: night baseball. FDR expressed the hope “that night games can be extended because it gives an opportunity to the day shift to see a game occasionally.” This was more than a green light for Griffith’s desire to have as many night games as he could; it was a fat one down the middle. The Senators had held their first night game on May 28, 1941, at Griffith Stadium and drew 25,000 people, which was a big jump over the normal daytime attendance in 1941 of fewer than 5,500 per game. Originally, Griffith was against night baseball because he thought it would be too expensive. But in 1939 he changed his mind when he attended a night game at Shibe Park in Philadelphia and saw firsthand the financial power of night baseball. The timing was perfect for Griffith to continue pursuit of a great revenue-generating tool. At the 1941winter meetings he proposed unlimited night games during the workweek. The American League supported his proposal, but not the National. The commissioner also voted against the expansion of night baseball.

However, it wasn’t over for Clark Griffith. At his meeting with President Roosevelt on January 14, 1942, Griffith seized the opportunity to put the topic on their agenda. It worked. After the Green Light letter, Commissioner Landis granted 21 night games to the Senators and 14 to each other club.

Griffith still wasn’t satisfied. He kept pressing the issue for unlimited night games for the Senators. He said he needed the additional revenue to serve the challenges of keeping a team operating during the war. On July 6, 1942, the owners voted on allowing night baseball for each weekday. Griffith lost on a decisive “no” vote cast by the commissioner. He continued his campaign in 1943 and he extended it to writing White House press secretary Stephen Early in early March of 1943. On July 13, 1943, Landis granted the Senators unlimited weekday night games. Other teams eventually caught up in July 1944. (Still, many ballparks did not have proper lighting for true night games until after the war.)

There was another opportunity for Griffith to generate attendance and to maintain Washington Senators operations during wartime: doubleheaders. He worked hard to get the league to lift restrictions on doubleheaders. On February 5, 1942, The Sporting News reported that Sunday doubleheaders could now be played on any Sunday instead of not until the fourth home Sunday.

This may have backfired on Griffith. It may have been a contributing factor to the Senators’ second-place finish in 1945. From August 19 to the end of the season, the Senators played 16 doubleheaders, seven in August and nine in September. In one stretch, they played eight doubleheaders in 13 days including three back-to-back twin bills. The Senators won 87 games but finished second, 1½ games behind the Tigers. Why such a grueling schedule? Griffith rearranged this part of the schedule to accommodate the practice schedule of the Washington Redskins, who used Griffith Stadium and paid rent to Griffith.

The Green Light letter said there would be baseball. Now Griffith and the other owners had to fill up major-league rosters and attempt to put competitive talent on the field while the players were subject to military service.

In 1941, even before Pearl Harbor, the Senators had lost some players. Although not key, established players, they might have been candidates to fill rosters during the war. Pitcher Lou Thuman had a two-year career of five games with an 0-1 record and a 12.00 ERA. Outfielder Jim Mallory had four games, 12 at-bats, 2 hits, 2 runs scored, and a .167 batting average. Outfielder Elmer Gedeon was in the minors in ’41, but had played five games in 1939 with three hits. Pitcher Lefty Brewer was a minor leaguer on the 1941 spring-training roster when he entered the military in March.

The crafty Washington Senators owner would need to be at his strategic and creative best to acquire players and get them ready to play. His chief talent scout, Joe Cambria, was a big help in solving this problem. Cambria scouted and acquired talent both inside and outside the US but he was especially good at acquiring inexpensive Latin American talent who would be draft-exempt under the Selective Service rules.

Cambria had found some players already for Griffith and he would find more. During wartime, players like pitcher Alex Carrasquel from Venezuela and Bobby Estalella and Gil Torres from Cuba played significant roles to help the team stay competitive.

From 1942 to 1945, Carrasquel served double duty as a relief pitcher and spot starter. He ranged from a low of 35 games pitched in 1942 and 1945 to a high of 43 in 1944. His record from 1942 to 1945 was 33-26 in 152 games of which he started 42 with 19 complete games. His ERA ranged from a low of 2.71 to a high of 3.68.

Before the 1942 season, the Senators reacquired the hard-hitting, poor-fielding Bobby Estalella, whom they had signed in the ’30s but lost to the St. Louis Browns in the draft. In 1942 his 68 runs and 65 RBIs in 133 games helped to replace the run production of some key hitters who were in the military.

Utility infielder Gil Torres, whose dad, Ricardo, played 16 games for the Senators and manager Clark Griffith in 1920, provided depth and flexibility to the 1944 and 1945 teams. He played in 134 games in 1944 and 147 in 1945. As a rookie Torres scored 42 runs, drove in 58, and posted a .267 batting average. In 1945 the average took a significant dip to.237, but he still contributed 39 runs scored and 48 RBIs.

Griffith also used Cambria’s Cuban connection to get effective supporting players like outfielder Roberto Ortiz in 1944 (85 games, .253 batting average, 36 runs, 35 RBIs). Catcher Mike Guerra played in 75 games in 1944 and 56 in 1945. Reliever Santiago Ullrich appeared in 28 games with a 4.54 ERA and a 3-3 record in 1945. Outfielder Jose Zardon played in 54 games in 1945 and had a .290 batting average in 131 at-bats.

However, Griffith’s breakthroughs in international signings did have critics among owners and fans because the players were draft-exempt. In April 1944 the Selective Service System ruled that foreign players would have to sign up for the draft or leave the country. On July 16 several players left the team and returned to Cuba. The policy change requiring draft registration or removal for foreigners was reversed before the start of the 1945 season.

Washington Senators: Years in Review, 1942 to 1945

1942 Season

Washington’s manpower took a big hit prior to the 1942 season. Two key run producers and some role players left for military service. In 1941 the Senators had scored 728 runs, fourth in the American League. The offense seemed to be moving upward. This was 63 runs more than in 1940 (but 137 runs less than the 865 of the top scoring club, Boston). Although the offense was improving, two of Washington’s top run producers would be in the military and not on the field in 1942.

Reliable-hitting third baseman and shortstop Cecil Travis, 28 years old, had one of his best years in 1941 even though Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak and Ted Williams .406 batting average made the daily headlines. Travis led the league with 218 hits, 25 more than DiMaggio and 33 more than Williams. Travis was second in the league in triples with 19 and second to Williams in batting average at .359, which was .002 points ahead of DiMaggio. Travis entered the Army in January 1942.

Buddy Lewis scored 100 or more suns in four of his six full years playing for the Senators as an outfielder-third baseman. He scored 97 runs in 1941. Lewis’s RBI production had a similar pattern with 72 or more RBIs in four of his six seasons with a career high of 91 in 1938. Lewis was drafted in 1941, received a deferment until the end of the season, and then joined the Army Air Corps.

The Senators had hoped that a pair of 24-year-olds, third baseman Hillis Layne and first baseman Jack Sanford, might help make up some of the run production lost by the Travis and Lewis departures. However, Layne and Sanford also wound up in the military in 1942. Red Anderson was also missing in 1942. He had started 1941 on a high note by catching FDR’s Opening Day pitch. He played a strong support role the rest of the season as a relief pitcher and spot starter. He appeared in 32 games, worked 112 innings, and had a 4.18 ERA with a 4-6 record. In 1942 he was in the Navy. He did not play in the majors again.

In 1942 the Senators finished seventh, 39½ games out of first with a 62-89 record. They scored 75 fewer runs than in 1941. Stan Spence (.323, 94 runs, 79 RBIs), Mickey Vernon (76 runs, 86 RBIs), and Bobby Estalella (68 runs, 65 RBIs) tried their best to fill the void created by the loss of Travis and Lewis. George Case, a regular since 1938 who continued to star for the Senators during the war years, hit .320 and stole a league-leading 44 bases. (Mickey Vernon was second with 25.)

Pitching performance declined in 1942. Washington’s staff gave up 817 runs, the most of any American League team during the war years. There were high hopes for the staff early on with the return of 34-year-old Bobo Newsom, but he went 11-17 with a 4.93 ERA and was sold to Brooklyn near the end of the year. Knuckleballer Dutch Leonard, the dependable veteran of the staff, pitched in only six games because of a broken ankle.

1943 Season

In 1943 the Senators surprised baseball fans with an 84-69 season and a second-place finish, 13½ games out. A highlight of the season was Buddy Lewis’s appearance at a doubleheader. An Air Force pilot, he had flown some VIPs from his base to the game. The Senators honored him between games. Lewis left before the second game to fly back to his base. However, there was a slight change in the expected routine. Before flying out of Washington, Lewis doubled back and buzzed Griffith Stadium so low that he was clearly recognizable to his teammates. Several protocols and regulations fell victim to his cheerful and creative goodbye. However, it was generally believed and never denied that Griffith took care of it.

Offensively, George Case was first in the league with 102 runs and 61 stolen bases. Mickey Vernon finished fifth in the league in runs (89) and stolen bases (24). Stan Spence was fifth with 88 RBIs.

Pitching was where Washington excelled this season. Washington’s staff lowered its ERA from 4.58 in 1942 to 3.18 in 1943. This was in spite of losing two reliable pitchers to the military, Sid Hudson and Walt Masterson. In 1942 the two had combined for 60 appearances, 382 innings pitched, and 15 wins.

But replacements, new and old, rose to the occasion. In his second full season, Early Wynn had his fastball flying to pitch 257 innings, third in the league, and pick up 18 wins. Dutch Leonard was back for a full season, with 31 games and 220 innings. Although he had only an 11-13 record, Dutch had a 3.28 ERA and a league-leading low of 1.9 walks per nine innings, quite an achievement for a knuckleball pitcher. Some new replacements helped the staff turn in a great performance. First-year pitcher Milo Candini, 25 years old, went 11-7 with a 2.49 ERA in 28 appearances, 21 as a starter. Mickey Haefner, 30 years old, also was new blood. He did double duty with 23 games in relief and 13 as a starter. He had his knuckler working to get his ERA to a sparkling2.29 to go with an 11-5 record. Another knuckleballer, 39-year-old Johnny Niggeling, came to the Senators in a late-season trade and posted promising numbers in only six starts: a 4-2 record and a 0.88 ERA.

1944 Season

In 1944 the Senators found their way to the cellar for the first time in 35 years, finishing 25 games out of first place with a 64-90 record. Both hitters and pitchers performed well below their 1943 effort. The offense scored 592 runs, a decline of 74 from 1943 and their lowest production during the war years. Mickey Vernon’s run-generating bat and base-stealing legs were in the military, not on the field. Slick-fielding second baseman Jerry Priddy and his 1943 production of 68 runs and 62 RBIs was also in military service.

First baseman Joe Kuhel, a steady hitter for the Senators in the 1930s who was reacquired from the White Sox before the season, scored 90 runs but produced only 51 RBIs. At 38, it was tough for him to completely fill the shoes of Mickey Vernon. Second baseman George Myatt, who turned 30 in June, stepped up from his 1943 reserve role to play in 140 games, hit.284, and score 86 runs but had only 40 RBIs. George Case, second in the league with 49 stolen bases, and Stan Spence, fourth in the league with 100 RBIs, continued to be the leading offensive players for the Senators. Catcher Al Evans and third baseman Hillis Layne returned from the war and showed their “baseball rust.” Layne had 87 at-bats in 33 games with a batting average of .195. Evans had 22 at-bats in 14 games and hit .091.

The pitching also tailed off. The team ERA rose to 3.49 as the staff allowed 69 more runs than in 1943. Roger Wolff, a 33-year-old knuckleball pitcher, was acquired from the Athletics before the season started. With four knucklers on his staff and with expert knuckleball catcher Jake Early in the military, Griffith reacquired 38-year-old catcher Rick Ferrell from St. Louis. The knuckleball corps of Leonard, Haefner, Niggeling, and Wolff had a 40-52 record. Wildness worked against the newcomer Wolff, as he walked 3.5 batters per nine innings. His Senators debut season consisted of only 4 wins and 15 losses.

1945 Season

In 1945 the Senators were back in the hunt for first place. In a close race, Washington finished second to Detroit, 1½ games behind, with a 87-67 record. The offense scored 622 runs, 30 more than 1944, even though it lost run producer Stan Spence and some key role players to military service. But it was pitching that improved the Senators in 1945. Even with four knuckleball pitchers, the pitching staff allowed only 2.8 walks per game; had a 2.92 ERA, lowest in the league; and tied pennant-winning Detroit with 19 shutouts.

Offensively, some unfamiliar names were key to the Senators’ success. George Case and George Myatt tied for second in the league with 30 stolen bases apiece. Myatt batted .296, and Case .294. Myatt contributed 81 runs and 39 RBIs while Case had 72 runs and 31 RBIs. The big run producers were 30-year-old rookie outfielder George “Bingo” Banks and the ageless Joe Kuhel.. Although he turned 39 in June, Kuhel did his best to replace Spence’s production. Joe had a .285 batting average, a .378 on-base percentage, and a slugging percentage of .400. This was the Joe Kuhel Senator fans remembered when he played for Washington in the ’30s.

War returnees also bolstered Washington’s attack. Hillis Layne, in his first full year back, contributed as a productive role player. In 61 games he hit .299, reached base at a .352 clip, and had a .408 slugging percentage.

Buddy Lewis was also back in late July, this time without a memorable flyover. In the war, Lewis logged many missions as a pilot in the China-Burma-India Theater (“flying the hump”) and earned a Distinguished Flying Cross. Lewis got to play in 69 games and had 258 at-bats, posted a stellar .423 OBP, and scored 42 runs and with 37 RBIs and a .333 batting average.

Cecil Travis’s return was shorter and not as productive. In 15 games, he had 54 at-bats with a .241 batting average, a .293 on-base percentage, and the worst slugging percentage of his career to that point, .315. Travis served his country well in the war. He earned a Bronze Star and four battle stars. During the Battle of the Bulge, as one of the “Battered Bastards of Bastogne,” Travis got frostbite and almost lost his feet. He survived but his career was never the same. He retired after the 1947 season at the age of 34.

Just as in 1943, the pitching staff made the difference between finishing near the top and dwelling on the bottom. With catcher Rick Ferrell’s help, the four knuckleballers, Leonard, Haefner, Niggeling, and Wolff, won 60 games and lost 43. Leonard and Wolff had ERAs under 2.50 and gave up less than two walks per nine innings, Wolff 1.9 and Leonard 1.5. Walt Masterson came back from the war late in the season to pitch 25 innings in four games with a 1.08 ERA and a hard-luck 1-2 record.

One of the biggest stories that season came in a 5-foot-7 package known as Marino Pieretti, born in Italy but brought to the United States when he was young. Griffith spent $7,500 in the 1945 Rule 5 draft to acquire the 23-year-old right handed Pieretti, who had a 4-F draft classification, from Portland of the Pacific Coast League. He had gone 26-13 with a 2.46 ERA with Portland in 1944. In the offseason Pieretti worked in a San Francisco slaughterhouse killing cattle with a sledge hammer.

Pieretti’s first year with the Senators was a career year. He pitched in 44 games, second best in the American League, with 27 starts, 14 complete games, and 3 shutouts. He had a 14-13 record with a 3.32 ERA, which would be the most wins and lowest ERA of his six-year major-league career.

Pieretti was a battler both on and off the mound. Late in the season fellow pitcher Alex Carrasquel picked Pieretti’s bat to use in his trip to the plate. The 5-foot-7 Pieretti confronted the 6-foot-1-inch Carrasquel, who then broke his bat, Pieretti responded with a right to the face. Carrasquel thanked him by slamming his broken bat on Pieretti’s left arm.

Players broke up the fight and resolved to keep it quiet. The press did find out. But as Frank “Buck” O’Neill reported in The Sporting News of September 20, 1945, such fights are “just indicative of the healthy spirit” of a team, even one collectively fighting for first place.

On August 4, 1945, in the second half of a doubleheader, “replacement player” Bert Shepard came to the mound at Griffith Stadium in the fourth inning with two outs and a runner on second. Washington was down 14-2 to Boston. Shepard struck out George “Catfish” Metkovich to end the inning. He pitched a total of 5⅓ innings in his only major-league appearance, giving up one run, three hits, and one walk.

In 1944 Shepard, a minor leaguer when drafted in 1942, had been shot down in a bombing raid over Germany. A doctor in a German POW camp amputated his right foot below the knee. At Walter Reed Hospital in Washington while being fitted for an artificial limb, Shepard met Undersecretary of War Robert Patterson. He told Patterson about his longtime wish to pitch in the majors. Patterson called Griffith, who arranged a tryout for Shepard at spring training in 1945. Shepard showed that his artificial limb could handle the routines of pitching and then reinforced the message in an exhibition game. Griffith put Shepard on the roster as a coach and he performed his duties well. On July 10 at Griffith Stadium, Shepard started and won an exhibition game against the Dodgers. He was activated to pitch in the August 4 game, his first and last. The war ended 11 days later.

RICHARD MORASKI is a long time Red Sox fan and first-time author from Naugatuck, Connecticut. Rich saw first-hand the impact of World War II on baseball. Two uncles went into the war as Sox fans and came back as Yankees fans; two other uncles were older and wiser. Currently retired from the Federal Government after working 36 years for the US Department of Agriculture as a Management Analyst, he uses his new-found time researching baseball, re-reading past issues of The Sporting News online and sharing his new baseball stories with his cigar-smoking friends. Rich is especially happy to be part of this project since his late brother, Leon, served in the military and graduated from West Point, class of 1959. Rich also worked several years for Senator Abraham Ribicoff (D) from Connecticut and taught as an adjunct professor in Quantitative Methods at American University where he earned a BA and MA.

Sources

Allen, Thomas E. If They Hadn’t Gone: How World War II Affected Major League Baseball, (Springfield, Missouri: Moon City Press, 2004).

Anton, Todd W., and Bill Nowlin, eds. When Baseball Went to War (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2008).

Gay, Timothy W. Satch, Dizzy and Rapid Robert: The Wild Saga of International Baseball Before Jackie Robinson (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2011).

Gilbert, Bill. They Also Served: Baseball and the Home Front 1941-1945 (New York: Crown, 1992).

Gilbert, Thomas W. Baseball at War: World War II and the Fall of the Color Line (New York: Franklin Watts, 1997).

Goldstein, Richard. Spartan Seasons: How Baseball Survived the Second World War (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co. Inc., 1980).

McKenna, Brian. Clark Griffith: Baseball’s Statesman (Lulu.com, 2010).

Stang, Mark Michael, and Phil Wood. Nationals on Parade: 70 Years of Washington Nationals Photos (Wilmington, Ohio: Orange Frazer Press, 2005).

Thorn, John, and Pete Palmer with David Reuter. Total Baseball (New York: Warner Books Inc., 1989).

baseball-reference.com

sabr.org/bioproject

The Sporting News

ballparks.com/baseball/american/griffi.htm