The Way the Game Is Supposed to Be Played: George Kell, Ted Williams, and the battle for the 1949 batting title

This article was written by Mark Randall

This article was published in Fall 2013 Baseball Research Journal

It was the last game of the 1949 baseball season and George Kell was locked in a close race for the AL batting title. The Detroit Tigers were playing the Cleveland Indians in a game that meant little to either team since neither was destined for the World Series.

It was the last game of the 1949 baseball season and George Kell was locked in a close race for the AL batting title. The Detroit Tigers were playing the Cleveland Indians in a game that meant little to either team since neither was destined for the World Series.

Ted Williams, who had sat atop the league’s hitters for most of the season, had been held hitless earlier in the day by Vic Raschi, while his arch-rivals the Yankees clinched the American League pennant. The “Splendid Splinter” had started the month of September with a 12-point lead and seemed certain to win his fifth batting championship.1 Kell, who had been hampered by injuries in September and was down seven points in late September, had been on a hitting tear that brought him within three points of Williams on the season’s final day.

Word filtered down from the press box to the Detroit dugout that Kell was now ahead of Williams in the race. If his lead held he would be the first third sacker ever to win the American League batting championship. (Debs Garms led the NL in hitting in 1940 with a .355 average but split time at third and the outfield.)

The slick-fielding third baseman knew in the eighth inning that he was leading Williams by a threadlike margin. He had already banged out two hits on the day against the tough Bob Lemon, a double his first time up and a line-drive single to left on his second trip to the plate. Lemon walked Kell to lead off the sixth, coughed up three runs, and was replaced by the Indians’ other fireballer, Bob Feller. Kell flied out to left in the seventh against Feller. With the score tied 4–4, there was a chance that Kell would bat again. He didn’t want to, but he also didn’t want to come out of the game and win the batting crown by sitting on a stool in the clubhouse.2 Another hit would secure his edge over Williams. A base-on-balls would leave things unchanged. If Feller retired him, then Kell would drop behind Williams.3 When the home half of the ninth inning opened, the Tigers were leading 8–4, and three batters were ahead of Kell. Johnny Lipon, batting for Neil Berry, grounded out. Dick Wakefield, batting for Hal White, smashed a single to first off Mickey Vernon’s glove.

Next to bat was Eddie Lake. Lake ended up hitting a two-hopper to Ray Boone at short, for a game-ending double play. An elated Kell threw the three bats he was holding in his hand “as high into the air as I could.”4 He had won the batting title by a couple of decimal points. It was one of the closest batting races in baseball history. The Tigers star had thwarted a bid by Williams for his fifth batting crown by two ten-thousandths of a point—.34291 to .34276. If Williams had managed one more hit or one fewer at-bat, he would have his third Triple Crown—a feat never achieved in the game.5

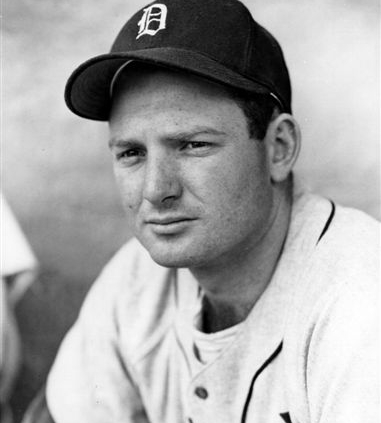

George Kell was already one of the American League’s best players when the 1949 season began, a rare accomplishment in an era when the men who played his position were known primarily for their glovework.6 Establishing himself as a star, though, did not come easily. The sandy-haired third baseman from Swifton, Arkansas, got his start in baseball in 1940 with Newport, a Class D team affiliated with the Brooklyn Dodgers, only eighteen miles from Kell’s hometown. When the team found itself in need of a shortstop late in the season, the local postmaster in Swifton, who attended almost all of Newport’s games, talked the general manager into giving Kell a try.

Kell had demonstrated his skills locally in American Legion ball, but found playing in the minors harder than he expected. He batted a mere .160 in 48 games and wasn’t much better in the field. He was invited back to Newport the next year and led the league with 143 hits. His .310 average was third in the league and he was the top fielder at his position.7 At the end of 1941, Newport sold his contract to Durham, a Class B club in the Dodgers organization. The team had plenty of third basemen, so when the manager asked if anyone could play short, Kell volunteered. Kell recalled in his autobiography that he got half a dozen hits, but committed the same number of errors. Brooklyn general manager Larry MacPhail saw Kell play and demanded the club get rid of him, saying, “He’ll never be a ballplayer.”8

Kell was heartbroken when he was released and came within a “rabbit’s hair” of quitting baseball.9 But he caught a break with Lancaster, which needed a second baseman. Kell found manager Tom Oliver and talked his way on to the team. He batted .299 for Lancaster and was voted the team’s most valuable player. Kell returned for the 1943 season and opened the eyes of Connie Mack by hitting a phenomenal .396 in 138 games for Lancaster, which was the highest average in all of baseball. His 220 hits were also tops in the league and Kell was again voted MVP. Lancaster had an agreement with Mack and the Athletics, giving the A’s their pick of any three players, and an eager Mack made a special trip to scout him. Kell recalled: “He had watched us play a double-header. And in the clubhouse afterwards he came over to me and asked, ‘Young man, how would you like to come to Philadelphia?’ That’s all there was to it.”10

The A’s brought Kell up at the end of the 1943 season to play one game at third base. He hit a triple his first at-bat on September 28, 1943, to drive in a run. “I tried to act very calmly, like it was just another time atbat for me,” Kell wrote in his autobiography, Hello Everybody, I’m George Kell. “But I was dying to pinch myself to make sure this was really happening.”11

Kell became the team’s regular third baseman in 1944, batting a respectable .268 in 139 games, and helped the Athletics post their second-best record in ten years with a fifth-place showing and a 72–82 win-loss record. Mack exercised patience while the rookie worked out his rough spots. Kell improved on those numbers in 1945, batting .272 and more than doubled his output of extra base hits including 30 doubles and four home runs. Kell also established himself as the league’s top defensive third baseman, leading the league in assists, putouts, and fielding average, and along with Dick Siebert at first and Ed Busch at shortstop gave the Athletics a solid and consistent infield.12

Although the same infield performed admirably in 1945, the Athletics fell to 52–98. Kell banged out 154 hits and had 56 runs batted in. But with the war over, Mack knew that veterans would be returning to their former teams. His war-years players would be unknown quantities against returning pitchers like Bob Feller.13 (Kell was rejected for military service because of bad knees.) Kell worked hard in 1946 to prove he could play at the All-Star level, but in early 1946 Mack made a move. Kell was batting .299 when he unexpectedly found himself traded to the Detroit Tigers. The A’s were in desperate need of an outfielder who could hit, while the Tigers were looking to replace their aging third baseman, Pinky Higgins, who had not played in 1945 and was 37, older than they would have liked. Third base was a weak spot for the Tigers, who had no promising recruit coming up.14

Kell led the American League third basemen in fielding that season. Several American League clubs were interested in trading for Kell. Tigers Manager Steve O’Neill had tried to make a deal to acquire Kell the year before, but Connie Mack had refused every offer. This time, O’Neill offered Mack his choice of eight players. Mack chose Barney McCosky, a proven veteran and solid hitter. It was a straight trade with no cash involved.

Kell had just finished breakfast in the Book-Cadillac Hotel in Detroit where the A’s were staying when Mack got on the elevator with him and told him that he had been traded to the Tigers. Kell was shocked and didn’t want to go. He was playing every day. He hustled. And Mack seemed to like him. He felt like an orphan, like nobody in the world wanted him to play baseball for them. “It was such a shock and felt like a rejection,” Kell recalled. “But Mr. Mack told me, ‘George, you’re going to be a good ballplayer, and I’m sending you to a team that will pay you the kind of money that I can’t.’ As it turns out, it was the greatest day in my life.”15

Kell figured the Tigers must have wanted him to trade away an established star like McCosky. The 29-year-old McCosky was a fan favorite who had helped the Tigers win the pennant in 1940. From 1939 through 1942, McCosky had hit .311, .340, .324, and .293. He joined the Navy in 1943 and rejoined the Tigers in 1946, but at the time of the trade was in a bad batting slump, batting only .198, and had been benched recently with a leg ailment that had bothered him for weeks.16 Kell was batting right around .300 and in 16 times at the plate against Detroit pitching had hit safely seven times (.438).17 Weeks before the trade while the Tigers were playing in Philadelphia, O’Neill told sportswriters that “Kell is the best third baseman in the majors.”18

Fans at the time were left wondering if the Tigers knew what they were doing by trading one of their favorite players for a third baseman they had never heard of. “I felt like Cinderella being traded for the Queen of the Ball,” Kell wrote in his autobiography.19 H.G. Salsinger, a sports writer for The Detroit News, urged the fans to relax. “Kell, at the age of 23, faces a future that should establish him as one of the game’s best third basemen,” Salsinger wrote in his column. “He is fast, quick, alert, aggressive. He has an excellent throwing arm. He is intelligent. In a day when good shortstops are plentiful and good third basemen a rarity, Kell stands out. He may stand out even more with added experience.”20 And the way he figured it, the Tigers picked up Kell just in time. According to his sources, the Red Sox had been on the verge of getting Kell before the Tigers completed the deal. Boston had offered Mack his choice of any outfielder with the exception of Ted Williams.21

Kell didn’t let the talk affect his play. In his first appearance with his new team, he got a hit in both games of a doubleheader against Boston and contributed at least two spectacular fielding plays. After the initial nervousness wore off, Kell came to love playing in Detroit and hit .327 the rest of the year as a Tiger. “It was an excellent place to play ball,” Kell wrote. “And the city was a beautiful place in which to live. There wasn’t a day I didn’t enjoy playing in Detroit.”22 The fans, too, soon warmed to Kell and it was the beginning of a great romance. By August, Kell found his groove and made Detroit fans forget McCosky. It didn’t hurt that there were a lot of fans in the stands from Arkansas—including what seemed to Kell like half the population of Jackson County, where Swifton was located—who had come to work in the automobile factories following the great migration from the South after the war. He finished the year with a .322 average and would go on to hit over .300 in each of the next five seasons as a Tiger. Kell was also an All-Star in every one of those seasons and led American League third basemen in fielding average in 1946, 1950, and 1951.

The trade to the Tigers had been the best thing to happen to his career. “Every time I would see Mr. Mack after that I would thank him for what he had done for my career. Mr. Mack had done me a favor,” Kell recalled.23 The Tigers had found the man they so desperately needed to shore up the hot corner. Tigers center fielder Doc Cramer once pointed to Kell and told a reporter who was looking for a story, “Nobody seems to know it, but he’s the best third baseman in the American League. Look up his record.” Coach Frank Shellenback, who overheard the conversation, agreed. “You’re right about that, Doc,” Shellenback added. “I’ll tell you one thing about Kell; he has a great pair of hands and a fine arm. Why, I have yet to see him make a real bad throw across the diamond, either to first base or second. And he’s getting to be a real good hitter too.”24

In 1947, Kell hit .320 with 93 RBIs, which he said “was pretty good for a second place hitter.” Despite being a .300 hitter, Kell developed a reputation as a “bad ball” hitter. He sprayed hits all over the field and, according to writers Mark Stewart and Mike Kennedy, “changed his stance and swing depending on the pitcher and situation. He inside-outed pitches to the opposite field, but could also turn on inside deliveries and pull them down the left-field line” and was a good drag bunter.25 “I don’t have a particular pitch I like,” Kell said in a 1950 profile. “I just go up to the plate and the first good one I see I swing at it. It doesn’t have to be in the strike zone to hit.”26 Tigers manager Red Rolfe said Kell was all brains at the plate. He studied pitchers’ tendencies, often outguessing them and setting them up to throw the pitch he was looking for. “He hits all kinds of pitching—fast or slow,” Rolfe said. “He’s the steady kind that managers like.”27 Four-time batting champ Harry Heilmann praised his hitting style, saying, “instead of swinging blindly at the ball, [Kell] is always looking for weak spots in the defense and punching a hit through them.”28

Kell entered the 1949 season with something to prove, after 1948 had turned out to be what he considered the worst season of his career. While he kept his string of .300 alive with a .304 mark, Kell was limited to only 92 games that year because of two major injuries—both suffered at the hands of the New York Yankees. Kell broke his wrist in early May on a fastball by Vic Raschi and was out of the line-up for nearly four weeks. Then, any hope of salvaging the season ended in late August when a grounder from Joe DiMaggio took a high bounce and struck Kell in the face, breaking his jaw. Kell instinctively scrambled for the ball and forced the runner at third then passed out. “I had to prove I could bounce back from a few bad breaks and still be the same player I had worked so hard to become,” Kell wrote in his autobiography.29

Although already an established major league hitter, Kell picked up “one of the greatest batting tips I ever learned in my life” while on his way to spring training in 1949. In March Kell and his wife and kids spent the night at the Tuscaloosa Hotel in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. In those days, players drove down to Florida for spring training. Tuscaloosa was the halfway point to Lakeland from Kell’s home in Swifton and he liked to stop there for a night before finishing the journey to camp. Also staying at the hotel was Boston Braves star pitcher Johnny Sain, who was from Walnut Ridge, Arkansas, not too far from Swifton. Kell had told Sain about the hotel and he began to stop there as well. After spending the night, Kell decided to run downstairs for a quick cup of coffee and some toast before hitting the road. When he got to the coffee shop, Sain was sitting at a table with St. Louis Cardinals’ stars Red Schoendienst and Stan Musial, who were on their way to the Cardinals camp in St. Petersburg. Kell was delighted when they motioned him over to join them.30

After some small talk about what they did over the winter and what they hoped to accomplish during the season, Musial began talking about hitting. He told Kell that he went into spring training every year knowing that he was going to hit somewhere between .320 and .340 for the season. Musial was at a point in his career where his confidence in himself would not let him fall short of his goals. Kell went back up to his room thinking that Musial’s advice “was the most amazing thing about hitting that I had ever heard in my life. He was talking about confidence. A player simply cannot become a good hitter without it.”31 Kell made up his mind that from them on that he would hit somewhere between .310 and .325 every year.

While he realized he would never be a great hitter like Musial, Williams, or Joe DiMaggio, Kell figured that if he concentrated hard enough he knew he could post solid numbers at the plate and make the All-Star team every year. It wasn’t until after the season was over and he realized that he had won the batting championship that he fully appreciated what Musial had said.

In 1949, Ted Williams was having one of the most dominant offensive seasons in baseball history. Williams had already won four batting titles, including the last two, and Kell had said all along that Williams would be the man to beat for the batting crown. Kell was fairly consistent through the 1949 season, but never gave much thought to winning the batting title because Williams always looked like he was on the verge of piling up ten hits in his next 15 at-bats to make a joke out of the batting race. It wasn’t until the All-Star break that anybody mentioned Kell’s name in the same breath as the batting title. Kell hit .348 in April, .330 in May, and .392 for the month of June and his overall batting average hovered in the low .350s. Williams, by comparison, hit .306 in April, .343 in May, and .304 in June and was batting around .320.

With a .341 average and a league-high 63 hits in 185 times at the plate, Kell took over the AL batting lead from Gus Zernial after the hard-charging Chicago rookie was sidelined by an injury. Zernial was hitting .355 in 138 times at bat when he injured his right shoulder in a game in Cleveland on May 28 while diving to catch a sinking line drive hit by Thurman Tucker. He landed on his shoulder and cracked a bone in five places. Williams was batting .317 and leading the league with 14 home runs and 48 runs batted in. Kell would also lose time to an injury when he broke his right foot on June 21 in a 7–1 loss to the Red Sox in Boston, and wouldn’t return to the Tigers lineup until July 2. Kell was batting .353 to Williams’s .315 at the time of the injury.

Williams garnered 88 hits in July and August, hitting a torrid .387 and .405. and took over the batting lead from Bob Dillinger on August 2 with a .348 average. By the end of August, Kell trailed Williams .344 to .356. Williams cooled off though in September, hitting only .279 for the month. From September 1 to September 13, Kell had 12 hits, but missed the next seven games as a result of a broken thumb. “In the last couple of weeks of the season, I got hot and piled up a carload of hits to make the race tight,” Kell recalled.32

On September 18, Williams smacked two home runs and drove in six—and held a ten-point lead over Kell with ten games left in the season. Kell returned on September 23 and went 2-for-3 to raise his average to .342. That same weekend against the Yankees in Fenway Park, Williams belted two home runs and remained ahead of Kell at .349 as Boston and New York battled for the pennant. Kell’s Tigers had four days off leading up to the final weekend of the season while Williams and the Red Sox played three games in Washington and two games in New York. Williams went 1-for-10 in Washington and 1-for-3 in the first game in New York to drop his average to .346. Kell then went 1-for-5 in the next two games against Cleveland, while Williams went 1-for-6 with one game to play. Going into the final day of the season, Kell trailed Williams .341 to .344.

The pennant would be decided by the final game of the season. At Yankee Stadium, Williams walked twice and was held hitless in two official at-bats that day by 20-game winner Vic Raschi, as the Yankees beat the Red Sox 5–3 to capture the pennant. The Tigers, meanwhile, were playing Cleveland where Indians starter Bob Lemon squared off against Detroit’s Virgil Trucks. Kell recalled in his autobiography that he got a call that Sunday from his wife, Charlene, who was already back at their Swifton home, with some words of encouragement. “You’re going to lead the league in hitting,” she said. “I know you can.” Kell told teammate Hoot Evers what his wife had said. “She’s right,” Evers replied.33

Evers told Kell that if he got two hits that day that he would win the title. Kell, however, was skeptical that he could beat out Williams. He figured that Williams would likely get a couple of hits on the day. “I remember answering that Williams would probably get it,” Kell recalled.34 Getting two hits off Bob Lemon wouldn’t be easy. Evers told Kell to go out there and get them his first times up. In his first at-bat, Kell rifled a double to center. His next time up, Kell lined a single to left.

Cleveland held a 4–0 lead in the sixth, but the real drama was focused on Kell. Lemon walked Kell, then gave up three runs before being relieved by Feller. Cleveland was trying to finish in third place which was worth another $1,200 to $1,500 per player. Feller was the last guy Kell wanted to see. “I always felt that Bob Feller was the toughest pitcher I ever faced. Lemon was a close second. Together, they were a one-two knockout punch that floored almost every American League hitter,” Kell recalled. Facing Feller was “always as much fun as getting a tooth pulled without any pain killer.”35 Kell flied out to left against Feller in the seventh, but there was still a possibility that he would have to face Feller again. Kell was scheduled to bat fourth in the ninth inning.

Lynn Smith, a baseball writer for the Detroit Free Press, had called New York and found out that Ted Williams had gone hitless against the Yankees. He called down to the dugout to let manager Red Rolfe know that Kell was ahead of Williams in the batting race and that if he didn’t bat again, he would win the batting title. Lipon grounded out to third and was followed by Wakefield, who singled to bring up Eddie Lake. As Lake settled into the batter’s box, Kell heard catcher Joe Ginsberg yelling to him from the dugout. Rolfe wanted to put Ginsberg in to bat for Kell to make sure he would win the batting title, and was trying to let him know that he was going to hit for him.

Kell had no idea what Williams had done on the day, but remembered that Williams had not sat out the last day of the 1941 season when he was hitting at .400, and insisted on batting. In 1941 Williams had a .399955 batting average which would have been rounded up to .400 if he had chosen to sit out a season-ending doubleheader. Williams ended up banging out six hits in the two games.

Kell was sitting on a 2-for-3 day. He decided he was going to win it or lose it right there. “I said, ‘I’m not going to sit on a stool and win the batting title,’” Kell recalled. “I didn’t want to bat again. I felt I had to. I wasn’t about to back into a batting title against him.”36 With Kell kneeling in the on-deck circle, Eddie Lake hit the first pitch up the middle to shortstop Ray Boone, grounding into a double play and ending the game. Kell celebrated by throwing his bats in the air. The batting title was his, with honor.

“I don’t think I could have faced Williams or anybody else walking into the clubhouse and saying, ‘No, I’m not going to hit,’” Kell remembered.37 Feller told Kell at the 2005 Baseball Hall of Fame ceremony in Cooperstown, New York, that he was aware that Kell was on the cusp of winning the batting crown. “I knew what was going on,” Feller said. “I would have walked you or hit you.”38

The race was so close that in order to decide who won the batting title it was necessary to figure their averages down to the ten-thousandths of a point. Baseball had seen close batting titles before. In 1945, Snuffy Stirnweiss of the New York Yankees beat Tony Cuccinello of the White Sox by .00009. The 1949 title marked the third time that a batting championship ended in a virtual tie. The other one was in 1931 when three players, Chick Hafey (.3489), Bill Terry (.3486), and Jim Bottomley (.3482) finished less than a point apart in the National League. Kell was declared the winner by virtue of outhitting Williams .3429 to .3428 and was the first third baseman to win the batting crown since Heinie Zimmerman in the NL in 1912.

Kell not only edged out Williams, but his 13 strikeouts that year was the lowest total for a batting champion since Willie Keeler in 1898, who had struck out only four times. Kell was also second in the AL in doubles (38), fourth in triples (9), and ranked in the top ten in twelve other categories, including on-base percentage and slugging, and came in eighth in MVP voting. Kell had achieved something he had dreamed about for seven years. It was also the twentieth time that a Tigers player had led the league in hitting. Ty Cobb won 11 titles between 1907 and 1919. Harry Heilmann won it four times in the 1920s. Sam Dungan (1899 Class A Western League), Heinie Manush (1926) and Charlie Gehringer (1937) each won a single batting title.

“I’ve had my eye on that title ever since I broke into the majors,” Kell said, when notified he had officially been certified as the American League batting champion for 1949. “And I don’t think anything could make me happier.”39 Kell reflected in his autobiography: “I can’t express how I felt when the news finally sunk in. Winning the American League batting title is one thing. Beating out Ted Williams to do it made it even more special.”40

He now felt that he had earned his place among the league’s best. Actually, the league’s top hitter might have been neither Kell nor Williams, but Joe DiMaggio. The “Yankee Clipper” finished with a .346 average but illness and injuries limited his play to 76 games and only 272 times at bat, far shy of the 400 at-bats then required to be eligible for the batting title.

For Williams, losing the batting title and Triple Crown was a disappointment. However, while he missed winning his fifth title by less than a point, the slugger still led the league with 43 home runs and tied for the lead in RBIs with 159. Williams also led the league in on-base percentage (.490), slugging (.650), plate appearances (730), runs scored (150), total bases (368), doubles (39), and walks (162). He was also voted the American League’s Most Valuable Player. The following season Williams walked across the field when the Tigers and Red Sox met for the first time and shook Kell’s hand. “You won the batting title,” Williams said. “So I’m coming to your dugout.”41

Kell set out next season to prove that 1949 was no fluke. “One thing I really want to do is lead the league again in hitting,” Kell said. “So many people criticized me and called me a cheese champion last year. I want to prove I can do it again.”42 He would go on to have an even better season at the plate in 1950, almost winning a second batting title, finishing second to Billy Goodman of the Boston Red Sox. Goodman was a parttime player who filled in for Williams when he ran into the left-field fence and broke his elbow in the All-Star game. Goodman proceeded to belt the ball at a good clip.43 The 24-year-old Goodman finished with a .354 average and 150 hits in 424 at bats in 110 games. Kell batted .340, but led the league with 218 hits and 56 doubles and a career high 114 runs and 101 RBIs.

In a 1950 profile, sportswriter Ted Smits commented that Kell had gone from being a “brilliant fielder, but no great shakes as a major league hitter,” to a player who “all he does is field flawlessly and hit any kind of pitch.”44 Manager Red Rolfe added, “He came up the hard way. A lot of supposedly good judges of talent thought he would never make the grade. But Kell has proved that major league baseball takes just average ability plus a lot of determination and ambition.”45

Although Kell would go on to hit .319 in 1951 and again lead the league in hits (191) and doubles (36), he was surprised when he found himself traded to the Red Sox in 1952 in one of baseball’s biggest post-war trades. The deal was a whopper—baseball’s first million-dollar swap.46 The Tigers shipped Kell and outfielder Hoot Evers, along with regular shortstop Johnny Lipon, and relief pitcher Dizzy Trout, to Boston for slugging first baseman Walt Dropo, outfielder Don Lenhardt, infielder Johnny Pesky, Bill Wight, and Fred Hatfield.

The biggest surprise was Kell’s departure. Tigers General Manager Charlie Gehringer didn’t want to trade Kell, but Boston insisted he be part of any deal. “There is no way we wanted to move you,” Gehringer told Kell. “But every time we got close to a trade [Boston General Manager Joe] Cronin said there’s no deal if Kell isn’t a part of it.”47 The Tigers were in last place and headed nowhere. Gehringer wanted to do something to shake up the club. “He hadn’t been helping us enough while we were in the cellar, so we gave him up to get some long ball punch in Dropo and Lenhardt,” Gehringer explained to the press. Detroit had offered the star third baseman to Boston in 1951 in exchange for Ted Williams, but the Red Sox turned the deal down.48

Kell was just as shocked by the news as the rest of the baseball world. He loved playing in Detroit and the trade had left him more confused than the one that had sent him there six years earlier. “I wasn’t angry,” Kell wrote in his autobiography. “By this time I realized that anything was possible in baseball. I just couldn’t figure out why it happened. I was in the lineup every day. I hit .300 and made the All-Star team every year. What does a player have to do to make himself secure in this city?”49

But if he had to be traded, he was glad it was to Boston. Boston was in the thick of a pennant race. In his nine years in the majors, Kell had never played on a pennant winner and he was going to make the most of it. He characterized the swap as a “record climb,” telling reporters, “I jumped from a last place club to one in first place. In a single day I made a gain of 10 1/2 games in the standings. That’s hard to beat.”50 While he never wanted to leave Detroit, he was getting the Green Monster, Ted Williams, and all the charms of New England. “I sure didn’t want to leave Detroit,” Kell said. “But the only thing that made it better was going to Boston because that’s the other great baseball town in the American League.”51

The ex-Tigers made an immediate impact, helping to lead Boston to a 13–11 victory over Cleveland. Kell and Evers each hit home runs and drove in three runs apiece. Kell reached base 18 times in his first 30 plate appearances with the Red Sox, and finished the year with a .311 batting average.

Kell had hoped to finish his career in Detroit, but at least the trade to Boston gave him the chance to play alongside Ted Williams, the best hitter he had ever seen. “There was nothing Ted Williams could not do with a bat,” Kell wrote in his autobiography. “He had the most beautiful swing that God ever gave one man. Every time he went to the plate he put on a clinic for hitting. He was always thinking hitting. He knew exactly what a pitcher was going to throw in every situation. He was never intimidated. He was the intimidator.”52

Kell was a little concerned that Williams might be upset with him for costing him the Triple Crown in 1949, but Williams welcomed him. “You’re going to love this park,” Williams said. “It’s a great place to play and you should have been here all the time.”53 Kell said in 2005, “we were primarily a young ball club and he was an elder and I was past 30, so we hit it off real good.”54 Williams was a tough man on the outside, but according to Kell, was a gentleman and “was always quick to give credit to players. If he was your friend, he was behind you all the way.”55

In fact, Williams admired Kell. When asked in 1951 who he thought the most dangerous batter was as a rival for the batting title and as a threat to pitchers, Williams, without a pause answered: “Kell, of course. He just goes along hitting steadily all the time. Take a look at his averages. There may be players getting more publicity for their hitting, like Gus Zernial, but Kell always is up there right near the top, and he’ll stay there. He’s a good hitter for he moves around in the box, pulling and punching the ball.”56

At the National Baseball Hall of Fame ceremony in 1997, Williams joked with Kell about their batting race 48 years earlier. “Here’s the man who beat me out of the Triple Crown in 1949,” Williams said to their fellow Hall of Famers.57

Kell told Williams that for a long time he didn’t realize that he had cost Williams the Triple Crown. Williams reassured him that, far from being upset, he admired the way Kell battled with him the whole season. “Hell no,” Williams said. “You beat me fair and square, the way you’re supposed to. It was a great race. I loved it. That’s the way the game is supposed to be played. I’m glad I got a chance to play with you.”58

MARK RANDALL has been an award-winning journalist for the past 15 years. He has covered a number of beats for newspapers in Massachusetts, New Mexico, Florida, Utah, Alabama, Arizona and Arkansas. He holds a bachelor’s degree in history from Northeastern University, a master’s degree in broadcast journalism from Syracuse University, and a second master’s degree in history from Arkansas State University, where he has also taught undergraduate history courses.

Photo credit

George Kell, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Notes

1 H.G. Salsinger, “First A.L. Batting King at Third Base.” Detroit News, December 23, 1949.

2 David Hammer, “Cooperstown Brings Back Memories For Hall of Famer Kell.” Associated Press, August 3, 2005.

3 Sam Greene, “Kell King By .0002.” Detroit News, October 3, 1949.

4 Tom Gagne, “Quick Question & Answer with Hall of Famer George Kell,” Baseball Digest, September 2001, 54.

5 Harold Friend, “If Ted Williams Had Only Gotten One More Hit.” Bleacher Report. June 2, 2010. http://bleacherreport.com/articles/400159-if-ted-williams-had-only-gotten-one-more-hit.

6 “George Kell: Man with a Plan.” http://www.jockbio.com/Classic/Kell/Kell_bio.html.

7 Jockbio.com.

8 Jockbio.com.

9 Kell, 22.

10 Ed Rumill, “AL Best 3rd Baseman? K-E-Double L. And Here’s Y.” Baseball Digest, October 6, 1946, 48.

11 George Kell and Dan Ewald, Hello Everybody, I’m George Kell. Champaign, IL: Sports Pub., 1998. 42.

12 Dale Smith, “George Kell: A Tiger in A’s Clothing.” Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society. July 10, 2004. http://philadelphiaathletics.org/george-kell-a-tiger-in-as-clothing/.

13 Smith, “George Kell: A Tiger in A’s Clothing.”

14 H.G. Salsinger, “Makes Debut Today.” Detroit News, May 19, 1946.

15 Bill Dow, “Hall of Famer George Kell a Fan Favorite in Detroit.” Baseball Digest, July 2006, 65.

16 “A’s Swap Kell for McCosky.” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 19, 1946.

17 “A’s Swap Kell for McCosky.”

18 “A’s Swap Kell for McCosky.”

19 Kell, 43.

20 H.G. Salsinger, “With Youthful Kell at Third, There’s No Room for Pinky.” Detroit News, May 20, 1946.

21 Kell, 46.

22 Kell, 50.

23 Kell, 47.

24 Rumill, 46.

25 Jockbio.com.

26 Ted Smits, “Heilmann calls Kell ‘Quarterback’ at the Plate.” Associated Press, September 12, 1950.

27 Smits, “Heilmann calls Kell ‘Quarterback’ at the Plate.”

28 Smits, “Heilmann calls Kell ‘Quarterback’ at the Plate.”

29 Kell, 55.

30 Kell, 68.

31 Kell, 68.

32 Kell, 69.

33 Kell, 70.

34 Gagne, 54.

35 Kell, 70.

36 David Hammer, “Cooperstown Brings Back Memories For Hall of Famer Kell.” Associated Press, August 3, 2005.

37 Harry King, “Kell Back Home After Fire, Remembering Hall of Fame Career.” Associated Press, June 3, 2002.

38 King, “Kell Back Home After Fire, Remembering Hall of Fame Career.”

39 “Kell Batting Champ of American League.” Associated Press, December 23, 1949.

40 Kell, 72.

41 Jockbio.com.

42 Ted Smits, “Shot at Series Kell’s Big Goal.” Associated Press, September 14, 1950.

43 Associated Press. “Kell-Hatton Trade Puts Goodman In Infield Lineup.” June 4, 1952

44 Ted Smits, “George Kell determined to be a ballplayer.” Associated Press, September 11, 1950.

45 Ted Smits, Associated Press, September 14, 1950.

46 “May Go down as Baseball’s First Million Dollar Deal.” Associated Press, June 4, 1952.

47 Kell, 76.

48 “Sox Reject Kell Trade For Ted.” Associated Press, October 10, 1951.

49 Kell, 76.

50 Tommy Devine, “Switch to Red Sox Delights Kell: ‘I Expect to Hit Plenty Off It’”. Boston Globe, June 4, 1952.

51 Bill Dow, “Hall of Famer George Kell A Fan Favorite in Detroit.” Baseball Digest, July 2006, 65.

52 Kell, 79.

53 Kell, 80.

54 Baseball History Podcast. http://baseballhistorypodcast.com/2011/11/29/baseball-hp-1147-george-kell/.

55 Kell, 80.

56 “Ted Williams Believes Kell Is Most Feared Batsman.” Associated Press, May 28, 1951.

57 Kell, 80.

58 Kell, 80.