The Young and the Restless: George Wright, 1865–68

This article was written by Robert Tholkes

This article was published in Fall 2016 Baseball Research Journal

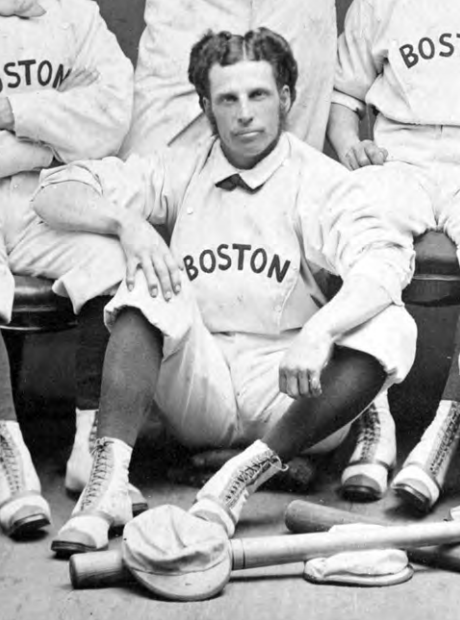

George Wright at the peak of his baseball career, with the Boston Red Stockings in the 1870s. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Baseball Hall of Famer George Wright’s record for changing clubs as a young player (1865–68) was exceptional even for this pre-reserve-clause period: six baseball teams (one of them twice, and omitting his cricket clubs) in four cities in four seasons, all before he was of an age to cast his first vote. He moved again for 1869, famously, to the Cincinnati club.

In George’s early years the family meal ticket was cricket. His father, English emigrant Sam Wright, was a cricket professional for the St. George Club of New York, as was older brother Harry Wright. Harry had also been a baseball player since 1858, when he joined the Knickerbocker Club.

George, born in Harlem on January 28, 1847, played with St. George’s first eleven as a substitute as early as July of 1862. He was an all-rounder—batting and bowling—from the start. In August 1862 he was top scorer for the firsts in a match with East New York, while teammate and fellow baseballist James Creighton took most of the wickets as bowler.1 George was in the eleven again in October, in a match where brother Harry acted as scorer and father Sam as umpire. (As professionals for St. George, they normally did not play interclub matches.) This was the match against the Willow Club of Brooklyn during which Creighton suffered the hernia he would fatally rupture playing baseball a few days later. The New York Clipper, in its issue of October 25, 1862, listed 15-year-old George among the professionals to receive the proceeds from a benefit match (the first type of match for which admission was charged), indicating that he assisted Sam and Harry in some way. The club continued to classify him as a member of the second, or reserve, eleven, presumably because of his age, for which it was criticized following one of his efforts as a substitute with the first eleven: “George Wright, also, considering he is rated a second eleven player by his club, is entitled to credit for his 9 (runs). A second eleven, all of his strength, would whip the first easily…”2 Answering an inquiry in its issue of August 22, 1863, from a reader in the Boston area, the Clipper commented: “George Wright is a son of the veteran cricketer Sam Wright… George is now one of the best players here, and bids fair soon to be the best.”

In September 1864, Wright played against two Philadelphia cricket clubs, the Philadelphia and Young America, and it was perhaps this exposure which earned him an offer in the spring of 1865 to become a full-fledged professional for the Philadelphia club. This may have involved instructing college boys of about his age—the Philadelphia was equated the following season to the Graduate Eleven of the University of Pennsylvania.3 He was still listed as a member of the Gotham as late as March 1865, but in June starred for a combined Philadelphia eleven against a visiting New York team.4 Besides any increase in compensation, the St. George Club’s problems that spring may have influenced his decision to transfer: the club lost its Hoboken grounds at the beginning of April and were in danger of losing its players to other teams.5 As cricket clubs did not forbid dual memberships (the National Association of Base Ball Players, or NABBP, did), he continued as a member of the St. George Club, playing with them as his schedule permitted. In 1865 he played with a New York club in the US vs. Canada grand match in Toronto.6 His family background was strong, and there was a war on, but even so, at cricket Wright qualifies as a phenom.

Immersed from his earliest memories in a sport that already recognized professionals, George Wright was the most prime of candidates to join the growing ranks of compensated baseball players as soon as his talent justified it. Arranged employment and waived club dues had been considered acceptable evasions of the National Association of Base Ball Players rule forbidding compensation since its adoption in 1859. At a time when few boys completed high school or dreamed of attending a university, this type of “professional” status for players of his age—he didn’t turn 21 until 1868—was not unheard of. At age 19 in 1860, for example, pitcher James Creighton of the Excelsior of Brooklyn was undoubtedly compensated.

To this point (1865) baseball played a distinct second fiddle to cricket for Wright. The 18-year-old’s senior baseball experience, following an earlier experience for the Gotham’s junior club, consisted of ten interclub matches with his brother Harry’s team, the Gotham of New York. The first had been in 1863, in which he played left field and was praised for “doing great execution among the high balls batted in that direction…”7 The next nine matches followed in 1864, when his batting was only average for the club—2R3 hands lost and 2R2 runs per game.8 They won three, lost six, and tied one. His fielding was ahead of his batting at this stage: he played all nine games at catcher, the most demanding position in those days of bare-hand, frequent-base-stealing baseball, when a pitcher might make 300 pitches per game. Previously, he took part in senior exhibitions pitting 18 cricketers against nine baseballists in baseball matches, some of them benefits staged by the St. George Cricket Club for his father and brother. At the first such, in September 1861, the 14-year-old, playing for the 18s at “second catcher” (close to the spectators), he had an unexpected opportunity to further his practical education: “Ladies’ crinolines made an excellent third catcher for stray balls, and little Georgy Wright must have done some damage to the aforesaid garments of some of the fair dames, by running amuck with his head into them in search of the ball to save a run.”9

Despite Wright’s move to Philadelphia for 1865, baseball did not drop off his agenda. Joining the Olympic Club, he began playing catcher for them in July, appeared in five games, and was also recruited while in New York at the end of July to substitute for the Keystone Club of Philadelphia during its visit to Greater New York. In total he found time for six interclub baseball matches in 1865, averaging 2R2 hands lost and 2R2 outs per game. He also was recruited to umpire two games in Philadelphia. Finally, the New York Herald on August 9 reported that George had played a match for his old club, the Gotham, up the Hudson at Newburgh, New York, under the name Cohen, presumably as a substitute for Leonard Cohen, a Gotham regular, on August 1. This is not corroborated by another source.

In March 1866, Harry Wright accepted an offer to captain the Cincinnati Cricket Club. He packed up his family and left for Ohio forthwith, and was quickly replaced as cricket professional for the St. George club by George. George also returned to the Gotham Base Ball Club. He played in five games, averaging 1R4 hands lost and 4R1 runs per game, which led the team. By this time he was considered an elite baseballist. Henry Chadwick, listing the best players by position in the Clipper on July 21, named him as catcher.

Wright is listed in the 1866 Gotham box scores as “George”—an unexplained deviation. Pseudonyms in 1860s box scores are far from unknown, and are usually ascribed to players who were illegally “revolving” with other clubs or who didn’t want their employers to know that they were playing hooky from the office. However, there is no indication that he continued to belong to the Olympic Club of Philadelphia after he rejoined the Gotham, and as he was compensated in some form, the second possibility does not seem to apply. Certainly no one was deceived. In the lone Gotham box score which is accompanied by a statistical summary, he is listed as “Wright” in the summary, and the Gotham’s 1866 player statistics in the 1867 Beadle’s Dime Base Ball Player also list him correctly.

The Gotham in 1866 played interclub matches only infrequently, and only one of their seven games was with first-tier opposition. That, and George’s developing skills in baseball, may account for his decision in July to resign from the club and enroll as a member of the first-tier Union Club of Morrisania, a then-independent town in the modern South Bronx. Waiting out the required 30-day membership period (which eliminates the possibility that he played for the Gotham under a pseudonym because he anticipated transferring), he debuted with the Union in September, and played their final nine games as they contended for the club championship of 1866. There he played for the first time at shortstop, his future specialty. The Union apparently preferred to keep Dave Birdsall, who would also be George’s teammate in the 1870s at Boston, at catcher. The change may also have been at George’s insistence—he remarked in later years that he moved to the infield after taking a foul tip in the throat. The club won eight of the nine, and finished with an overall record of 25–3. The Atlantic of Brooklyn, the champions of 1865, finished 16–3, but avoided defeat in a best-of-three series against any of its rivals, and so retained its unofficial championship. It did not schedule the Union, which was its prerogative. Wright averaged 1R3 hands lost and 4R6 runs per game, second on his team.

The New York Clipper noted in its cricket report of September 1, 1866, that “baseball has supplanted cricket in the affections of the lovers of out door pastimes in this country…” With baseball and cricket moving in opposite directions, Wright’s decision to leave the Gotham Club marked the reversal of their places in his plans: he staked his professional career for the foreseeable future on baseball. He never lost his affection for his first sport, however. He was a prominent amateur cricketer in the Boston area for many years after his retirement from baseball, competing well into his fifties.

Wright’s pocketbook likely dictated his next move. He resigned at some point from the Union Club. On November 12, before the Union had closed its season, he was in Philadelphia to play in a series of benefit games with some members of his 1865 club, the Olympic. The Philadelphia Sunday Mercury reported on November 18 that “we are glad to hear there is some prospect of [Wright] being again attached to clubs hereabouts.” In April 1867, apparently having spent the winter considering his options, he enrolled in the National Base Ball Club of Washington, DC. Though the “champions of the South” by virtue of triumphs in 1866 over teams in the District and in Baltimore, the National Club was second-tier by Greater New York standards, like the Gotham, but had ambitions of moving up. It had begun bringing in experienced players from Greater New York in 1866, and was looking for more.

Club president Col. Frank Jones was an official in the Treasury Department, and a resettled Brooklynite who had been a member of the Excelsior Club of Brooklyn before the war. As the new hands such as Wright were hired, they were listed as clerks in Treasury Department offices. For the 1867 season, eight of the top eleven players on the National were so designated.10 The National also offered a chance for George to visit brother Harry. It had announced in March that it would tour five “western” states in 1867, including two games in Cincinnati. Was Col. Jones expecting to replay the Excelsior’s success of 1860, when its tour of western New York had propelled it to immediate championship contention? Certainly one object of the tour was to let the newly-constructed team (the Excelsior were in a similar position in 1860) jell into a nine with the talent and cohesion to succeed in championship competition in September and October.

Wright upheld his end of the bargain. He led the team offensively, averaging 2R6 hands lost and 6R8 runs per game. His runs per game was the highest among players for first-tier clubs, and the National posted the highest per-game scoring average.11 The National posted a 25–5 record against NABBP-member clubs. A notorious sixth loss occurred on the western tour at the hands of the Forest City Club of Rockford, Illinois, in Chicago, and was generally attributed to the rigors of the tour schedule. The expected dividend of the tour in the form of first-tier contender status in the East, however, did not materialize, as the team afterward lost five of seven matches with Greater New York opponents. Postseason post-mortems pointed to a lack of discipline in the club, inconsistent fielding, the lack of a first-class pitcher, and the practice of moving players from position to position during a game. Wright’s experience is illustrative: despite his sterling reputation as a catcher and first-tier experience at shortstop, available box scores and game accounts from various sources (the box scores of the time listed only the position in which the player began the game) show him appearing in 12 games at second base, nine as pitcher, seven at catcher, six at third base, four at shortstop, and two in center field.

The captain (or field manager), Georgetown University law student George Fox, apparently took the blame for the post-tour failures. He resigned as captain in September and was replaced by Wright, who was even younger and had no experience as a baseball captain, but may have been thought the player most capable of exercising leadership with an undisciplined crew. It didn’t seem to take. A nadir of sorts was reached on October 21 when the team blew an eight-run lead in the ninth against the Union Club of Lansingburgh, New York. Covering the club’s loss to the Excelsior of Brooklyn, by then a second-tier club, in his issue of the Ball Player’s Chronicle on October 31, Henry Chadwick described the club’s condition during its late-October road trip to Greater New York: “George Wright is nominally the captain, but as each player of the nine, and two or three in particular, seem to consider themselves as fully competent to act in the position, the result is a lack of discipline, totally destructive of good generalship, be the nominal captain ever so capable of directing the nine.” As Wright was prone to the oft-criticized practice of moving players from position to position during the game (he played himself at four different spots in one of the losses), “ever so capable” probably doesn’t describe his abilities as a captain at this point in his career.12

Though the club offered Wright the captaincy for 1868 with a seat on the committee that selected the first nine, he apparently had had enough of clerking in the Treasury Department, and re-signed with the Union of Morrisania. The Unions had ascended to the unofficial championship of 1867 by winning a two-out-of-three game series from the Atlantic of Brooklyn, and then finishing the season without themselves losing a two-of-three game series to another club. They also had had to beat back an appeal by the Atlantic to the NABBP, on the grounds that the Union had used an ineligible player. Nevertheless, the Union’s record had declined from 25–3 in 1866 to 21–8 in 1867, and George was welcomed back, “at his own request.”13 This apparently occurred shortly after the end of the season in November; the New York Sunday Mercury was predicting his return to the Union by December 29.

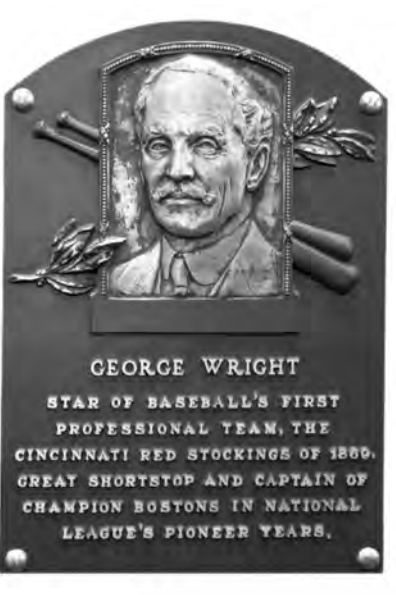

George Wright’s plaque in Cooperstown lacks the space to detail the most peripatetic period of his career.

At the beginning of March, Wright opened in New York, along with Harry, what the Sunday Mercury on March 1 called the “Wright Brothers Base Ball-Depot,” selling gear for several outdoor sports. This was his first foray into the occupation that would become his life’s work. George also returned to cricket, playing for Philadelphia in an interclub match in that city in May, for St. George on June 24 in Philadelphia, and in a series of matches against a visiting English eleven in September and October. His return improved the Union Club, which posted a record of 39–6. Unfortunately, two of the losses were to the Atlantic of Brooklyn, which deprived the club of its champion standing, which the Mutual Club of New York then won after defeating the Atlantic. Wright’s record in 43 games of 2R5 hands lost and 4R23 runs per game, was good for fourth overall among players on NABBP teams.14 An additional statistic, the number of times reaching base on hits, appears for the first time in some box scores: for 32 games, Wright accumulated 225, an average of over seven per game. Though the Union returned him primarily to shortstop (39 games), he inexplicably played second base in both of the losses to the Atlantic. He got another look at the “west” in August, as the Union went on a 20-game tour (including Cincinnati) that ranged as far as St. Louis. Answering an inquiry in the New York Clipper on September 26, Chadwick named Wright as the best “general player” in baseball.

The chronology of Wright’s next move, joining Harry on the all-salaried Cincinnati Base Ball Club for 1869, cannot be completely determined from the primary sources available. To an inquiry from Cincinnati printed on September 12, 1868, about the possibility that George would join the Red Stockings, the Clipper responded, “Not that we know of.” Since he played out the Union schedule, which ended on November 8, this presumably was not an accomplished fact. The NABBP then decided at its convention in December to recognize professional players and clubs. Cincinnati had decided, perhaps even before the NABBP’s action had to field an all-salaried team in 1869, which may have influenced his choice.

Definite reports of his transfer are lacking until February, so it seems unlikely that Wright had signed a contract before that point. The NABBP convention also voted to increase the period in which transferring players could not play for their new club from thirty to sixty days, effectively reducing the offseason signing period and making in-season transfers less likely. With the beginning of open professionalism, clubs were sorting themselves into all-professional, semi-professional, and amateur status. As of early January, 15 clubs, including the Union of Morrisania, were considered professional.15 The Union, however, after team meetings later that month, decided to abandon professional play and field an amateur nine. This decision likely was made after Wright (and other Union players) had decided to move on, rather than the other way around. The New York Sunday Mercury item on February 7 announcing the club’s decision listed the players transferring or retiring, Wright among them. Cincinnati, the Athletic Club of Philadelphia, and the Mutual were all reported to be interested in his services, and he was listed on an Atlantic of Brooklyn team that was headed for New Orleans in March.16

The speculation ended later in February: in its issue of February 28 the Sunday Mercury described Wright as on the “official list” of players who had signed with Cincinnati. The Red Stockings thus became the next club to try to achieve championship status by enrolling Wright, the acknowledged best general player in the game, following the unsuccessful attempts of the Nationals in 1867 and the Union in 1868.

George Wright’s peregrinations in his youthful years in baseball seem to have their causes in the permissive environment for player movement at the time, in his family background, and the fact that he was in an early stage in his career. The Sunday Mercury’s editorial on January 17, 1869, about “revolvers” prompted by the end of the decade (1859-1868) when compensation of players was contrary to NABBP rules, reflects the contemporary attitude in the baseball community to player movement:

REVOLVERS TO BE REPUDIATED. We are glad to learn that the principal clubs throughout the country this season intend repudiating the class of revolving professionals entirely, the majority of the organizations engaging the services of players, having become disgusted with the conduct of several players whom they had treated liberally in the hope of having them permanently in their clubs, but who finally either left them in the lurch at an important period of the season, or who forgot their indebtedness for favors received when tempted by the offer of better pecuniary receipts. We know of instances of players from Northern cities engaged by Western clubs, who after having been the recipient of pecuniary favors as well as cordial greetings and kindly welcome., have gone off to other clubs without so much as a by your leave. It is time such frauds as these were prevented. Now that professional ball-playing is a business, and that players can engage in it honestly and openly and above board, it becomes not only the honorable manly course to pursue, but also the best policy, to be strictly honest in all engagements with clubs…The revolving system would soon have its deathblow given it if clubs would refuse to allow a player to enter their nine who could not show a fair record—as regards honest dealing we mean—from the club he left. But as long as men are accepted, regardless of how they have acted with the clubs they have left, just so long may we expect to see revolvers flourish. Players may have good reason for leaving a club in the middle of a season; but when they do, the club taking them in should be thoroughly convinced of the fact. Now that the sixty-day law is in force, we shall expect to see less revolving; but the best way to put a stop to the odious system is for clubs to have an understanding among themselves not to employ players who cannot bring with them a clean record from their last place. For instance, suppose Joe Start, Geo. Flanly, Al Reach, Harry Wright, John Goldie, or half a dozen other well-known professional ball-players should desire to leave the clubs they belong to, there is not one of them who cannot point to his faithful services to the club he has been a member of as an honorable record sufficient to give him an engagement in any organization he may wish to join.

Earlier, contemplating player movement from the Atlantic Club before the 1866 season, the Sunday Mercury found a silver lining:

The changes which occur in the organization of the first-nines of our leading clubs each season, though they sometimes lead to unfriendly feelings and give rise to reports of unfair dealing, are nevertheless more beneficial than injurious to the game, inasmuch as a monopoly of success, year after year, tends greatly to lessen the public interest in the principal contests which take place…The excitement incident to a close match between two rival clubs is greatly promoted by the changes which occur in the formation of club-nines each year.17

George Wright was not included in the Sunday Mercury’s list of paragons considered above any suspicion of dishonest dealing, but had the same sterling reputation. Henry Chadwick, denying in the Ball Player’s Chronicle of May 21, 1868, an accusation of favoritism toward the Wrights, doubled down on their character:

We have been free in our praise of these two players for sundry reasons, among which, apart from their skillful play, may be named the following: We never knew either to be guilty of a dishonorable action; we have never known of either hanging idly about taverns and gambling houses; we have never heard from the mouths of either of them any blasphemy or profanity, or seen either give way to ill-temper or “ugliness”…we are glad to be able to hold them up as examples to professional players.

By contrast, two examples of unacceptable behavior occurred in early 1869 involving Wright’s intended team, the Red Stockings. The team in 1868 had employed an easterner, John Hatfield, a star catcher- outfielder. Hatfield over the winter took “pecuniary favors” from the Mutual Club of New York, but then attempted to rejoin the Red Stockings, and was listed as a Red Stocking in most preseason commentaries. He ended up with the Mutual: possibly the upright Harry sent him packing. Also so listed was a young Philadelphian, John Radcliff, an infielder-outfielder, who also ended up back east after similar reports.18

Abuses notwithstanding, never in professional baseball’s subsequent history would the “free agent” market seem so favorable for players. Honorably done, a mobile player could offer his services freely to the numerous professional and semi-professional clubs nationwide, and have no fears for his reputation or his employability. It was only required that he play for one club at a time and be a club member for 30 days before playing, limitations adopted in 1857 after a notorious instance of revolving in 1856. Although the waiting period between appearances for his old and new clubs was increased to 60 days for 1869 to discourage mid-season player movement, the assumption was still that a player should have the right to change employers on the same basis as anyone else. In a “labor market” with little or no restriction on player movement and dominated by independent clubs which hired professionals in competition with each other, Wright was almost inevitably going to make career moves among different employers. When this utopian labor market ended after the 1879 season with the secret adoption of the reserve clause, he became one of its first victims. Not wishing to return to Providence after the 1879 season, he was unable to obtain his release and chose to prematurely interrupt his playing career.

A player of George Wright’s unattached circumstances, reputation, and ability thus had in the period from 1865 to 1868 almost no limitations in his freedom of movement, and obviously Wright believed it was in his best interest to use it. That attitude ran in the family. The youthful George Wright operated against a backdrop of membership in a family of professional sportsmen who responded when opportunity knocked. Father Sam, though he settled down with the same New York cricket club for many years, had emigrated from England to better his career. Harry Wright preceded George in successfully combining cricket and baseball, and himself moved as a baseballist from the Knickerbocker Club to the more competitive Gotham Club amateurs to professional Cincinnati, even though by that point he had a family to uproot. Their relationships, and particularly Harry’s role in George’s career decisions, are however primarily a matter for conjecture. Perhaps it is significant that none of the primary sources even hint at a role for Harry in George’s movements, other than, finally, as a team captain interested in his services.

Wright’s moves are typical for an advancing young professional. He moved from junior to senior play, first in cricket and then in baseball, in association with his father and brother. He then decided as an 18-year-old that his best option was a promotion to cricket club professional, even if it meant splitting his time between New York and Philadelphia. Harry’s move to Cincinnati created an opening for George in New York in 1866, and in the same year the progress of his baseball skills allowed him to move first from junior play to a second-tier gentleman’s club playing a limited schedule and then to a first-tier championship contender, presumably with increases in compensation. In the absence of any other likely reason, his move to Washington in 1867 seems to have been financial. That club seeming in the grip of indiscipline and mismanagement, he returned to Greater New York City in 1868, with the financial resources in hand to invest in the Wright Brothers Base Ball Depot. As the present era of open professionalism dawned in 1869, however, the sun was setting on George’s period of hopscotching. He was at the baseball pinnacle as a player, and at the top of its new wage scale. He also had had his first experience as a sports entrepreneur, which would make him one of the most prosperous and respected of the pioneer baseballist. That and his longevity (he lived until August 1937) ensured his election to the Hall of Fame.

ROBERT THOLKES of Minneapolis is a veteran contributor to SABR publications and to the journal “Base Ball,” concentrating on the game’s amateur era. Bob’s past activities include several years as an officer of the Halsey Hall Chapter (Minnesota), biographical research on major leaguers with Minnesota connections, and service as newsletter editor for SABR’s Origins of Baseball Committee.

Notes

1. New York Tribune, August 29, 1862, 8.

2. New York Clipper, September 12, 1863, 170.

3. Philadelphia North American, May 4, 1866, 1.

4. Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 27, 1865, 2.

5. Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times, April 8, 1865.

6. New York Herald, August 25, 1865, 5.

7. New York Sunday Mercury, September 13, 1863.

8. The only widely-kept statistics for individual player performance until the late 1860s was total number of outs made and total runs scored, divided by games played. “2R2” indicates two runs per game with a remainder of 2.

9. New York Sunday Mercury, September 22, 1861.

10. Washington Evening Star, August 5, 1867, 1.

11. Beadle’s Dime Base Ball Player, 1868, 66, 97.

12. New York Clipper, November 2, 1867, 235.

13. The Ball Player’s Chronicle, January 23, 1868.

14. Beadle’s Dime Base Ball Player, 1869, 61.

15. New York Sunday Mercury, January 10, 1869.

16. New York Sunday Mercury, February 7, 1869.

17. New York Sunday Mercury, May 6, 1866.

18. New York Sunday Mercury, February 28, 1869.