‘They Beat Us the Japanese Way’: The San Francisco Giants’ 1970 Spring Tour

This article was written by Steve Treder

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1960-2019

The San Francisco Giants – a party of more than 60, including players, management, and staff, plus embedded sportswriters – boarded their chartered Japan Airlines jet at Tokyo’s Haneda Airport on the damp gray morning of Tuesday, March 31, 1970. Among the players, the prevailing mood was one of relief that their two-week ordeal in Japan was finally ending, spiked with a sense of annoyance at having to pull this damn slog in the first place. From their perspective, the tour – while offering bits of fun and adventure – had mostly been an exercise in discomfort, exhaustion, and competitive humiliation.

The San Francisco Giants – a party of more than 60, including players, management, and staff, plus embedded sportswriters – boarded their chartered Japan Airlines jet at Tokyo’s Haneda Airport on the damp gray morning of Tuesday, March 31, 1970. Among the players, the prevailing mood was one of relief that their two-week ordeal in Japan was finally ending, spiked with a sense of annoyance at having to pull this damn slog in the first place. From their perspective, the tour – while offering bits of fun and adventure – had mostly been an exercise in discomfort, exhaustion, and competitive humiliation.

Yet the club owner, 67-year-old Horace C. Stoneham, was settling into his first-class seat in a more ambivalent state of mind. To be sure, he was aware of the unhappiness among the players, and that pained him. Whatever else he was, Stoneham was an owner who cared deeply about his players – it would not be an exaggeration to say that he loved his ballplayers – and frustrating his boys, disappointing them in any way, was the last thing he ever intended to do. But as the operator of the business, he had broader concerns, and chief among them was the increasingly urgent need for cash revenue. The 1970 spring-training tour of Japan had netted the Giants a fat payday, something that was getting harder to find these days. This fact steeled Stoneham, reassuring him that, despite the trip’s problems, his decision to go was the right one. He’d done what he needed to do.

Moreover, beyond the cold hard accounting, these two weeks of on-the-ground, in-the-flesh examination of the state of Japanese baseball had kindled in Horace Stoneham a familiar old sense of wonder and excitement, of boyish eagerness for the future. He hadn’t personally been over to Japan in 10 years (though he had engaged in long-distance baseball business with his Japanese friends and associates), and the progress and power now vividly demonstrated by Japanese baseball – not just as a modern business, but as a cultural spirit – delighted Stoneham. Even when things are at their toughest, he knew, when it all looks bleak, there’s always a fresh new way to go. The Giants owner knew this. His life’s work had demonstrated it to him, in so many ways. You just had to be looking for the new opportunities, and to make yourself ready for them. That was the thing. That was always the thing.

Lefty’s Giants

There was never any American major-league ballclub more indelibly connected to Japanese professional baseball than these Giants, whose full ownership Horace Stoneham had inherited from his father in 1936. Their first opponent on this tour’s schedule was none other than the perpetual powerhouse Yomiuri Giants – so christened in the spring of 1935 by their strategic adviser Lefty O’Doul.1 He named them in specific honor of the New York Giants, O’Doul’s final major-league team. The Yomiuri lads would forever be clad in Giants-style black-and-orange caps, uniforms, and regalia.

When O’Doul was in New York with the Giants, he and Stoneham came to know each other well. When O’Doul’s career took him back to San Francisco, he and Stoneham sustained a good relationship. In 1945-46 their paths crossed again, when Stoneham’s Giants affiliated O’Doul’s Seals into their farm system, and in that period (as well as later), O’Doul was widely rumored as a candidate whenever Stoneham was thought to be pondering a managerial change.

It was through the O’Doul connection that Stoneham’s Giants first toured Japan in the fall of 1953, and then again in 1960, at which point O’Doul was back on the (now San Francisco) Giants’ payroll as a hitting coach. In 1966, when O’Doul bought out his investment partners and became sole owner of the landmark San Francisco bar and restaurant bearing his name, the scuttlebutt was that he’d done it with the financial assistance of Stoneham.2 O’Doul would have been prominently engaged in the Giants’ 1970 Japan visit, too, but he’d so suddenly and sadly died in December of 1969. Among Lefty O’Doul’s vast legion of true friends distressed by his passing, not many had known him longer, or loved him more, than Horace Stoneham.

Readily taking the torch from O’Doul, the key organizer of the 1970 tour was 48-year-old Tsuneo “Cappy” Harada. A native of Santa Maria, California, the son of Japanese immigrants, the bilingual Harada was spared internment during World War II, and instead was inducted into the US Army to serve as an intelligence officer. After the war he remained in Japan and soon became one of the key figures working with O’Doul to help heal the deeply wounded American-Japanese relationship with the tonic of baseball. When Stoneham’s Giants moved to San Francisco, they hired Harada, officially as a scout, specifically as their direct agent within the realm of Japanese baseball.3

Shared Goals

The press accounts of the Giants’ 1970 tour reliably described it as a “goodwill” venture, dedicated to forging and expanding friendship between the two countries and their baseball communities. No doubt that much was true. But the tour wasn’t only that, or even mostly that. Fundamentally it was a business deal, designed and expected to deliver a profit to its sponsor, the Lotte Orions of the Japan Pacific League, as well as its invited guest star Giants.

And for Stoneham’s Giants, generating some extra income wasn’t just a luxury. After enjoying consistently robust attendance in their first 10 years in San Francisco, the Giants saw ticket sales plummet with the arrival of the Athletics in Oakland in 1968. Stoneham needed this business. The deal he negotiated had favorable terms: The Orions would underwrite the Giants’ expenses, while guaranteeing Stoneham $150,000 from the proceeds.

The Giants’ 1970 Japanese tour was a springtime visit, a first. All previous American excursions had taken place in the fall, at the conclusion of the US and Japanese seasons, and were thus understood to be “just fun” barnstorming exhibitions. Staging it in March instead made these games a part of the spring-training schedule for both the Giants and their opponents; while they were still exhibitions, these contests took on the purpose of training the participants for their coming regular seasons.

For the Giants’ opponents, any disruption to their normal springtime routine was minimal: they were training in Japan anyway, and now they’d get to test themselves with some games against a formidable US major-league ballclub. As for the Giants themselves, Stoneham was no doubt considering this jaunt to be comparable to the springtime barnstorming schedules that were customary in earlier decades, as big-league teams played their way home after initial training at their “camp” somewhere in the South or Southwest.

What Stoneham was perhaps not properly appreciating was that his 1970 ballplayers were too young to have experienced springtime barnstorming. These were creatures of the modern Cactus and Grapefruit Leagues, and they were accustomed to spring training (a) in balmy weather, (b) with minimal travel, and thus (c) allowing for extended daily and weekly routines of conditioning, practice, and in-game action – as well as American-style time off. To yank them away from Arizona in mid-March, put them on a marathon jet-lag-inducing flight to a faraway place notorious for cold and wet spring weather, and once there submit them to a wearying schedule that prohibited their usual daily routines, wasn’t the most player-friendly course of action.

Nor were the games themselves anticipated to be cupcakes for San Francisco. In the assessment of Harada, “Our club is going over there next week expecting that it won’t have any easier time playing their clubs than it has been playing American teams in Arizona. The Japanese teams used to be comparable to our Class A minor leagues. But that was some time ago.”4

On March 15, a few days before the US team was scheduled to depart for Japan, the San Francisco Examiner reported:

All of [the Giants players] are looking forward to the trip, but in varying degrees. Some fear the interruption of the normal spring training process could leave the Giants unprepared for the season opener at Candlestick. Others fear that cold weather in Japan could hamper them.

The same article noted that Stoneham was doing his best to cheer them up: He was providing everyone with $500 spending cash, and players did look forward to shopping for pearls, cameras, and stereo equipment.5

Bumpy Ride

The Giants’ flight from San Francisco, consuming nearly all of Wednesday, March 18, was an ominous start. Headwinds buffeted and slowed the plane, and the leg from Honolulu to Tokyo was itself a 10-hour barf-bag nightmare. When they finally landed in Japan, it was 45 degrees and windy.

A welcoming party greeted them at the airport. Giants manager Clyde King, addressing the thronging press, vowed that his club was there on serious business, ready to play hard. Moreover, he noted that the team from Candlestick Park was “not afraid of cold weather.”6

The next morning the groggy Giants boarded a bus that inched through the city’s monumentally snarled traffic to Tokyo Stadium. There they worked out. The wind at the ballpark was described as “colder than Candlestick’s notorious breeze,” blowing straight in toward home plate with “a knife edge.” Hitters taking batting practice attempted to warm numb fingers over a smoldering bucket of charcoal. The infield grass was reported as “green but skimpy,” while the springtime outfield was “still brown from the cold wind.”7

The next day they played their first game, and lost to the Yomiuri Giants, 6-5, in 11 innings. Sadaharu Oh belted two home runs, including a walk-off game-winner, and Shigeo Nagashima homered as well. The day after that, also at Tokyo Stadium, in 39-degree overcast weather, the host Lotte Orions defeated their guests, 4-3, this time in 12 innings. Despite the gloom, a hardy band of San Francisco Giants Boosters some 100 strong, all the way from California – in loudly colorful attire, contrasting sharply with the drably clothed Japanese fans – lustily sang “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” and traded cheers with the Lotte faithful.8

After the game the Giants embarked upon their first intra-Japan road trip. It didn’t go well. Having already checked out of their Tokyo hotel that morning, the players had to wait in a long queue to shower and change, because the ballpark clubhouse had only two showers, and the Americans weren’t keen on using the large communal soaking tub. Then, without time to eat, they were jammed onto a tourist-class flight to Fukuoka, over 600 miles distant, and from there, packed like sardines with all their gear into two small buses for a 2½-hour ride to their hotel. Neither conveyance was designed for 6-foot-tall passengers.

When they finally arrived at nearly midnight, the players were loudly displeased. As one veteran put it, “This is like the low minors.” Their ire was directed at travel arranger Cappy Harada. “Where’s Cappy?” they asked. “Why isn’t he here?” Alas, Harada was not there, having instead flown ahead with Stoneham to Kyoto, first class, to woo potential broadcast sponsors.9

In Shimonoseki the Giants at last won a game, though not without rancor. Lotte Orions manager Wataru Nonin complained that San Francisco pitcher Gaylord Perry was throwing a spitball:

Umpire Al Kuboyama warned Perry that if he continued to rub his fingers over the back of his head he would call those pitches balls. Perry pretended to not understand and imitated the umpire’s motion with his gloved hand. After Perry left the game he started to run in the outfield – a standard practice in spring training in the States – and umpire Kuboyama chased him off the field. King protested, but the Japanese were very serious about the whole thing.10

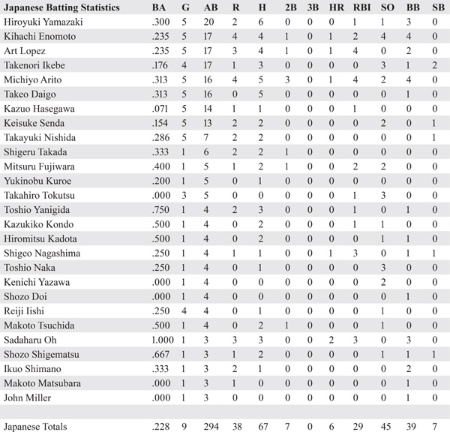

The Giants lost their next game, making it three out of four defeats to begin the trip. This was widely noticed, given that no previous big-league American barnstormer had encountered much competitive challenge in Japan. Willie Mays, reflecting on how different this was from his previous visit, in 1960, assessed that the Japanese “play much better today as a team. They make fewer false moves and fewer mistakes. They don’t make any bad throws and don’t throw to the wrong base. They run the bases better, hit behind the runner and sacrifice. They have been very well coached.”11

Sportswriter Jim McGee concurred, but believed that wasn’t the only thing making it hard for these Giants:

The improvement in Japanese baseball explains only in part why the Giants have been able to win only one game in four so far. The Giants record here does not mean that the Japanese are surpassing the Americans in baseball. There are other factors.

For one thing, the Japanese clubs are ahead of the Giants in conditioning. The Giants are far from ready to open the National League season. The playing conditions are primitive compared with American fields and clubhouses. The weather has been bitterly cold.

Also, the Japanese teams have been playing strictly to win while the Giants have been following spring training procedures – giving less experienced players a chance in every game. The Japanese managers change pitchers according to the situation, while manager Clyde King is letting his hurlers go a certain number of innings no matter what is happening.12

The tour then took the Giants to Osaka, and the weather only got worse: On the morning of March 25, they were greeted with snowfall. Willie McCovey, no stranger to knee trouble, visibly limped into the breakfast room. “My knee always hurts when it’s going to rain,” he observed, “but it didn’t tell me it was going to snow.”13

The snow let up to allow that day’s baseball, albeit with the temperature at about 50 degrees and the wind icy cold. The Giants played a doubleheader, beating the Lotte Orions 2-0 and losing to the Nankai Hawks, 9-0, along the way being shut out in three innings of relief pitching by Masanori Murakami, the former Giant. (The previous week a rumor had circulated that Stoneham was engaged in negotiations with the Hawks to reacquire Murakami in a trade; however valid that notion was, nothing ever came of it.)14

Former big-league second baseman Don Blasingame, who was with the Giants in 1960-61, had played in Japan for three years and was now a coach for the Hawks. He acknowledged the problematic spring weather:

“I told [current Giants’ second baseman] Ron Hunt in St. Louis last winter to wear his long underwear over here for the tour,” Blasingame said. “I’ve started spring training over here as early as January 27 and it does get cold. I don’t mind it though. I guess I’ve gotten used to it. It’s no colder than a night game at Candlestick Park. This year it is staying colder a little longer.”15

By this time, Stoneham’s wisdom at choosing to undertake the spring tour was being roundly questioned in the San Francisco press:

The difficulty … seems to lie with owner Horace Stoneham’s decision to pack up in the middle of spring training, upsetting the annual rites and leaving the Arizona sunshine to barnstorm in Japan. It’s cold and snowy over there and the surroundings are totally unfamiliar, and, well, it just isn’t anything like how a major league baseball player gets ready for the major league season.

“I don’t know what it is exactly,” Hal Lanier, the Giants’ veteran shortstop, was quoted the other day. “I mean, Japan is an interesting place and the people have been hospitable and all that. Most of the guys pretty much agree on the subject, all due respect to Mr. Stoneham’s decision to make the trip. It just isn’t the same, know what I mean? We’re supposed to be concentrating on getting ready for the season and trying to win a pennant. We hope this trip won’t hurt our chances.”16

The fed-up Giants players now did what they could to assert some control. The team voted to tell Harada and the tour management to change the schedule: Instead of staying in Nagoya on March 26 for a day off, they opted to return to Tokyo a day early and spend their precious leisure hours in the big city. Their frustrations were again articulated in the press: there was almost no opportunity for practice outside of the games, as even batting practice was limited to 15 minutes before each game; pitchers were unable to take their usual daily running in the outfield, because the ballparks were so small that they’d have to run in front of the outfielders instead of behind them; and moreover, Japanese fans were angered at the sight of pitchers running during a game, considering it an insult, a signal that the Giants weren’t taking the competition seriously.17

The Long-Term Perspective

Horace Stoneham, perplexed though he was by his players’ sour experience, was nevertheless able to perceive sweetness in the tour. His interest wasn’t only in making immediate money off these engagements. He was also keenly focused (notwithstanding his mid-1960s misunderstandings in attempting to recruit Murakami) on the development of Japan as a source of player talent for the Giants. Stoneham’s organization had been second to none in opening up the Caribbean region to major-league talent-harvesting in the 1950s and 1960s, and he believed that by investing in relationships and forging trusting partnerships in Japan, he could gain another competitive advantage here.

With that in mind, Stoneham was warmly encouraged by what he was seeing on this tour. Most obviously, the generation of young Japanese nourished from childhood by an ample postwar diet had simply grown taller and stronger than their elders. Stoneham assessed that the average height of the Giants’ opposing players in 1953 had been perhaps 5-feet-3, then jumped to about 5-feet-6 or 5-feet-7 in 1960, and was now getting closer to 6 feet. The drawback of Japanese players being too small was rapidly becoming outmoded.

And not only were modern Japanese players ever more athletic, they were vividly, as Willie Mays had observed, “well coached.” They demonstrated baseball technique and skill better than ever before, and if the top-tier Japanese leagues altogether weren’t quite major-league quality, they were clearly gaining ground. Unquestionably there were now several, perhaps dozens, of Japanese players capable of at least making the majors, if not excelling there. “In five years, the Japanese will be a source of players for American baseball,” Stoneham predicted. “The Japanese player will be a common sight on American clubs.”18

While that assessment rested upon a sound reckoning of the baseball talent issue, the assumption Stoneham displayed in making it was telling: It was right and proper, indeed inevitable, that the American big leagues would recruit all the best young Japanese talent for themselves. The best interests of Japanese ballclubs, and Japanese fans, weren’t part of the equation. Stoneham was plainly not anticipating that the Japanese professional baseball business itself, vastly better organized and more unified than any counterpart in Latin America, could and would refuse to accommodate the Americans in positioning Japan as just another major-league feeder.19

Yet there was another potentiality beyond even that, and this was one in which the interests of US and Japanese baseball might fully align: a high-level partnership. Perhaps a truly international World Series could be staged, and/or perhaps Japanese franchises could be incorporated into major-league baseball. What was emerging in Japan wasn’t just a cadre of world-class players, but a broader world-class baseball culture, and a tremendous fan base: a world-class baseball market.

It was this aspect of baseball in Japan that most captivated Stoneham. He was aware that the Japanese public consumed 13 daily sports newspapers, with most of the content for most of the year devoted to baseball. He noted that from his bullet-train window between Nagoya and Tokyo he’d seen countless kids engaging in baseball games all through the countryside. He was particularly struck by the image of one lone boy in a field, a husky teenager not attending to his farm chores, but instead swinging a bat, practicing his cut.

“You have to be impressed when you see them using any vacant space to play, including cobblestone streets,” said Stoneham. “The other day, I saw a group of boys going along the street carrying fishing poles and nets. I asked Cappy where they could fish because I couldn’t see water anywhere. He told me they weren’t going fishing. As soon as they found an empty lot, they’d stick the poles in the ground, put the nets on top and use them for a backstop for the catcher. Most of them were wearing getas, the shoes with wooden clogs. You haven’t seen baseball until you’ve seen a kid in his getas, running down a fly ball on a cobblestone street.”20

End of the Bumpy Ride

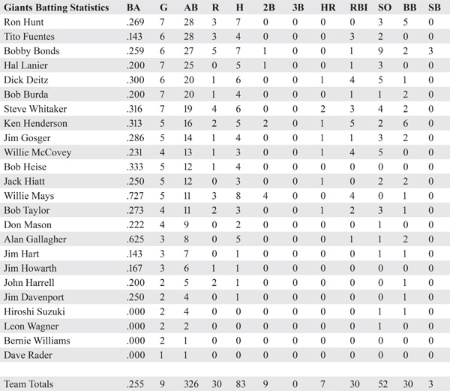

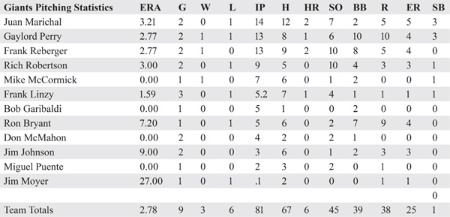

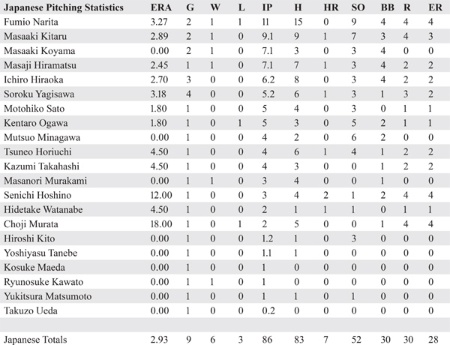

On Sunday, March 29, the Giants concluded their schedule with a 10-6 loss to the Orions at Tokyo Stadium. It was their least impressive performance yet: Gaylord Perry was riddled for seven runs in the first three innings, Ron Hunt crudely booted two grounders, and catcher Dick Dietz dropped a simple throw, botching a force out at the plate.21 The defeat finalized the team’s tour record at 3-6, by far the worst ever compiled by an American visitor to Japan.

Manager Clyde King squarely faced reality:

“The Japanese beat us completely. That was a fact. No alibis, no excuses. They beat us the Japanese way, with thorough preparation and planning. I knew they were laying for us and tried to get the club ready for what they had to face. We didn’t do the job, that was all there was to it.”22

The misadventure was hooted in the San Francisco press: Reporter Jim McGee, who traveled with the team, concluded that “the Giants lost face in Japan,” and commented, “[W]hat happened … was a blow to [the players’] professional pride. They are nettled that they were sent there virtually unprepared and are now being castigated for not playing better.”23 Columnist Prescott Sullivan put it bluntly: “The Giants made asses of themselves over there.”24

And to add illness to insult, ace pitcher Juan Marichal was one of several Giants players who came down with colds and flu on the tour – hardly surprising given the conditions. But Marichal’s bout was especially severe:

“We went to Japan and the weather was so cold. It was about 27 degrees, it was so cold. And the stadium was concrete all over which made it colder. And they don’t have any heaters in there or nothing. The only thing they have is charcoal you would burn to warm up, and quite a few players got sick. I was one of the guys that got sick, I caught a real bad cold.”25

By the time he returned to the States, Marichal had developed a respiratory infection, and was running a high fever. He was given multiple shots of penicillin, and that provoked a serious allergic reaction. He became dangerously ill, and had to be hospitalized. Marichal missed several weeks of play, and then pushed himself back to the mound before he’d regained his strength. For the first time in his brilliant career he was miserably ineffective, until at last rounding into form over the second half of the season.26

Whether it was caused by their tumultuous spring training tour or not – Marichal’s struggles surely didn’t help – the Giants started the 1970 regular season poorly. In late May, with the perennially contending team mired in fourth place, 12 games behind, Stoneham fired Clyde King.

The Lotte Orions in 1970 went on to enjoy a marvelous season, a pennant-winning 80-47 campaign. Spring training had presented no problems for them.

As for Horace Stoneham, his dreams of finding a competitive and financial revival for his Giants amid the gathering abundance of Japanese baseball were to be unfulfilled. Within five years, facing bankruptcy, he would be forced to put his beloved Giants – his family legacy and his life’s work – up for sale, and retire to Arizona.

STEVEN TREDER is the author of the 2021 Seymour Medal-winning biography Forty Years a Giant: The Life of Horace Stoneham. For many years he has been a presenter at Society for American Baseball Research meetings and at the NINE conference, and was a founding member of and longtime contributor to The Hardball Times. He is a lifelong resident of the Santa Clara Valley and holds degrees from Santa Clara University and Stanford University. When he grows up, he hopes to play center field for the San Francisco Giants.

(Click images to enlarge)

Notes

1 Americans have always routinely, and incorrectly, called this team the Tokyo Giants.

2 Dennis Snelling, Lefty O’Doul: Baseball’s Forgotten Ambassador (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 282.

3 Robert K. Fitts, Mashi: The Unfulfilled Baseball Dreams of Masanori Murakami, the First Japanese Major Leaguer (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015), 37-38.

4 Wells Twombly, “The Rising Sun,” San Francisco Examiner, March 12, 1970: 53.

5 Jim McGee, “O-Hah-O Not a State,” San Francisco Examiner, March 15, 1970: 50.

6 Jim McGee, “Giants Freeze in Japan,” San Francisco Examiner, March 19, 1970: 57.

7 Jim McGee, “Found: Candlestick in Tokyo,” San Francisco Examiner, March 20, 1970: 59.

8 Jim McGee, “Another Extra-Inning Defeat for the Giants,” San Francisco Examiner, March 22, 1970: C1.

9 Jim McGee, “Harada on Plane; Giants on the Bus,” San Francisco Examiner, March 23, 1970: 56.

10 Jim McGee, “Baseball’s Code of the Samurai,” San Francisco Examiner, March 23, 1970: 53.

11 Jim McGee, “Ten Years of Progress for Japanese Leagues,” San Francisco Examiner, March 24, 1970: 45.

12 McGee, “Ten Years of Progress for Japanese Leagues.”

13 Jim McGee, “A Frigid Split for Weary Giants,” San Francisco Examiner, March 25, 1970: 57.

14 “S.F. Preps for Japan Tour; Deal for Mashi Rumored,” Japan Times, March 18, 1970: 7. Murakami had pitched in 54 games for the San Francisco Giants in 1964 and 1965. For more on Murakami, see Robert K. Fitts, Mashi: The Unfulfilled Baseball Dreams of Masanori Murakami, the First Japanese Major Leaguer (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015).

15 McGee, “A Frigid Split for Weary Giants,” San Francisco Examiner, March 25, 1970: 57.

16 Dave Burgin, “Japan Trip: Grand Excuse?” San Francisco Examiner, March 26, 1970: 53.

17 Jim McGee, “Giants Win … Still Unhappy,” San Francisco Examiner, March 26, 1970: 53.

18 Jim McGee, “Japan: Baseball’s Shangri-La,” San Francisco Examiner, March 27, 1970: 47.

19 Indeed, during that very spring of 1970, the Giants signed two Japanese free agents, 22-year-old first baseman Hiroshi Suzuki and 25-year-old pitcher Kazuo Hiranuma. Both were assigned to the Giants’ Decatur (Illinois) Commodores farm club in the Class-A Midwest League. Both performed poorly there and were demoted in midseason to the Great Falls (Montana) Giants of the Rookie-classification Pioneer League, where they also performed poorly. That was the extent of the US professional career for both players, and there were no more such signings by any US organization until the 1990s.

20 McGee, “Japan: Baseball’s Shangri-La.”

21 The Giants committed 15 errors during the eight-game tour, leading to 13 unearned runs.

22 Jim McGee, “Japan’s Reaction to Giants: ‘Like Junks,’” San Francisco Examiner, April 1, 1970: 59.

23 McGee, “Japan’s Reaction to Giants: ‘Like Junks.’”

24 Prescott Sullivan, “What World Series?” San Francisco Examiner, March 31, 1970: 46.

25 Mike Mandel, SF Giants: An Oral History (Santa Cruz, California: self-published, 1979), 134.

26 Mandel.

27 Listed Japanese batters have a minimum of 4 plate appearances, all pitchers are listed. Yoshikazu Matsubayashi, Baseball Game History: Japan vs, U.S.A. (Tokyo: Baseball Magazine, 2004), 98; Nippon Professional Baseball Records, https://www.2689web.com/nb.html.