Tommy Lasorda: Baseball’s Global Ambassador and the Los Angeles Dodgers’ 1993 Friendship Tour of Japan

This article was written by Mark Langill

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1960-2019

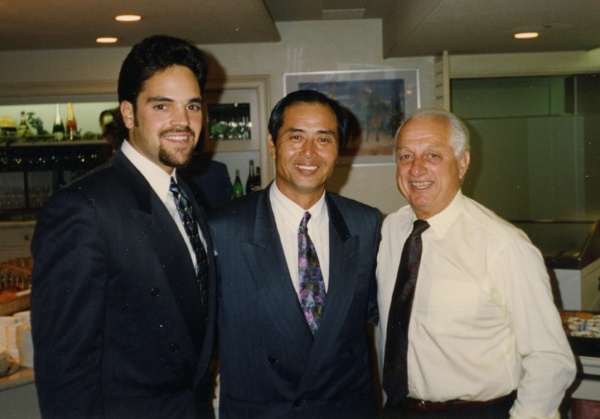

Mike Piazza, Sadaharu Oh and Tommy Lasorda (Courtesy of Mark Langill)

What felt like a nostalgia trip unexpectedly served as a dress rehearsal for the next frontier of professional baseball when the 1993 Los Angeles Dodgers staged a modest five-game “Friendship Series” in Taiwan and Japan.

Nobody could’ve predicted a “Tornado” on the horizon, one of the nicknames bestowed upon Kintetsu Buffaloes pitcher Hideo Nomo, who in 1993 was a four-time All-Star and former Pacific League MVP. His contract issues with Kintetsu led to his retirement from Japanese baseball after the 1994 season, an exit strategy discovered by agent Don Nomura when analyzing the sport’s seemingly ironclad working agreements covering the United States and Japan. Nomo became only the second player from a Japanese professional league – and the first in 30 years – to play in the majors during his National League Rookie of the Year campaign with the Dodgers in 1995.

“There was no business reason for the 1993 Japan trip, other than growing baseball at the international level,” said Fred Claire, a 30-year Dodger executive who was the team’s general manager from 1987 to 1998. “[Brooklyn Dodgers team President] Walter O’Malley’s global vision of the game was continued by his son, Peter. But when you go back in time, the thought of a player from Japan playing in the majors seemed like an impossible reach. There were no major-league teams scouting in Japan. There was no reason to use those scouting resources because there were players from Latin America, Mexico, and other parts of the world.”1

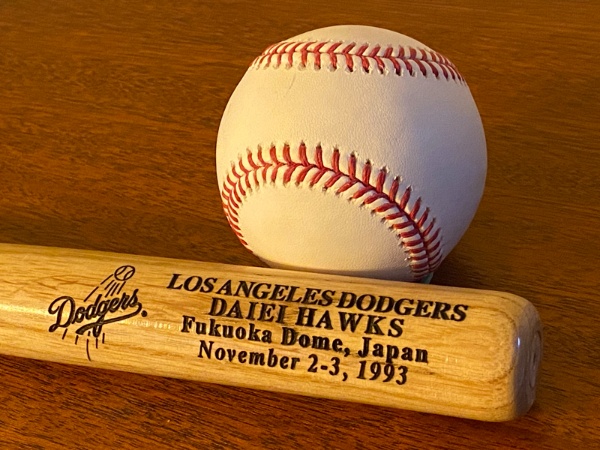

Manager Tommy Lasorda’s Dodgers became the first major-league team to play in Taiwan, posting a 1-2 record in Taipei against all-stars from the Chinese Professional League. Los Angeles then traveled to Fukuoka, Japan, for a pair of games against a combination of the Fukuoka Daiei Hawks of the Pacific League and the Yomiuri Giants of the Central League.

Nomo wasn’t part of the exhibition at the newly opened Fukuoka Dome in 1993. Claire didn’t stick around for the Japan portion of the trip, flying from Taiwan to Los Angeles and continuing to Naples, Florida, for a meeting of major-league general managers.

Instead of a stealth scouting mission, the 1993 trip represented another chance for Peter O’Malley to promote international baseball. He was 18 years old in 1956 when the Brooklyn Dodgers spent nearly five weeks in Japan after the World Series. His roommate was broadcaster Vin Scully, who reported on the 19-game exhibition for Sport magazine.

During their ownership of the franchise between 1950 and 1998, the O’Malley family used Dodgertown, the spring-training facility in Vero Beach, Florida, along with Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles after its 1962 opening, to host international events.

After selling the Dodgers to Fox Group in 1998, O’Malley kept his ties to the Vero Beach area, at one point operating a lease at “Historic Dodgertown” in a partnership with his sister Terry Seidler, Nomo, and former Dodgers pitcher Chan Ho Park, who in 1994 became the first player from Korea to appear in the majors. The Vero Beach complex was taken over by Major League Baseball in 2019 and renamed after Dodgers Hall of Famer Jackie Robinson.

The O’Malleys and Lasorda were also close to Rod Dedeaux, the University of Southern California baseball coach who won 11 NCAA titles during his 45-year tenure. Dedeaux played two games at shortstop for the 1935 Dodgers and was a longtime champion of international baseball. He coached Team USA in a baseball exhibition during the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo and in the 1984 Olympics baseball tournament at Dodger Stadium. (Japan defeated Team USA in the Gold Medal game.)

In a 1991 interview with the Mainichi Daily News, Peter O’Malley outlined his hopes for a true global baseball series. Dodger Stadium played host to the 1991 International Baseball Association World All-Star Game with top amateur players representing 28 countries.

I’m an advocate of such competition. And I think my colleagues in the majors are quickly becoming receptive to such an idea, too. I don’t think major-league baseball feels threatened at all. On the contrary, I get the feeling baseball’s leaders think the timing is just about right. Logistics – travel, etc. – are no longer a problem. Baseball is extremely popular and profitable outside the U.S. in many countries like Japan and Korea. The competitiveness is there. I think they feel now’s the time to capitalize on it and move on it.

It will be the best two teams going at it in a seven-game World Series. Say, the Los Angeles Dodgers and the Chunichi Dragons. But the international playoff would involve more than just the U.S. and Japan. After all, there are some strong Latin American leagues and the Korean pro league is coming on fast. It’s only been in existence for 10 years and look at how many competitive players there are. And pro ball is catching on in Taiwan. Plus, who knows where else the sport might also grow rapidly. The possibilities are endless and exciting.2

As publicity director of the Dodgers in the early 1970s, Claire accompanied Dodgers Alan Foster and Von Joshua along with a dozen other major-league players on a trip to Japan sponsored by the Nichiren-Shoshu Buddhist sect. As vice president of marketing in 1980, Claire, along with O’Malley, traveled to Japan to negotiate with Mitsubishi officials as the Dodgers became the first team with a color video scoreboard, debuting “Diamond Vision” at the 1980 All-Star Game.

Lasorda, who died in 2021 at 93, spent 71 years in the Dodgers organization. The former left-handed pitcher, bumped from Brooklyn’s 1955 roster to make room for rookie Sandy Koufax, first arrived in Japan in the spring of 1965 for a series of clinics with fellow scout Kenny Myers. Lasorda had also worked with members of the Tokyo Giants during the first of their five trips to Vero Beach between 1961 and 1980.

Lasorda’s 1965 arrival at the airport in Tokyo was fitting for a man still a decade away from international celebrity. Nobody met Lasorda and Myers at the airport because the baseball officials had the wrong date. The scouts went to the Hilton Hotel and rested after their nine-hour flight.3

During their three-week trip, Lasorda and Myers toured various landmarks and baseball facilities, including the Imperial Palace and the Olympic Village. Working with the Yomiuri Giants prior to their spring training, Lasorda gave tips to the pitchers. Myers, who converted Los Angeles prep track star Willie Davis into a left-handed-hitting center fielder, worked with Yomiuri hitters.

In his diary, Lasorda made notes on everything from his dinner reviews – “the most tender steak I ever ate” – to the training methods and facilities of his Japanese hosts.4 The lineup for manager Tetsuhara Kawakami’s 1965 Giants included outfielder Sadaharu Oh, third baseman Shigeo Nagashima, and lefty pitcher Masaichi Kaneda. All four Giants later had their uniforms retired, the same honor eventually bestowed to Lasorda by the Dodgers.

Our second day of training was just about the same as our last. The Japanese coaches believe in a lot of calisthenics and they spent about 2 hrs. a day on it. We work out from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. with no breaks in between. We had a meeting of the manager and the coaches. They asked our opinion of the day’s work and we gave it to them – they must concentrate more on the fundamentals. These people are anxious to learn – they want to surpass the Americans in baseball.

The pitchers here in Japan have no idea how to throw a curveball and no conception of throwing a changeup. I will have to concentrate on these two factors very much. The stars of the team, Nagashima, 3B, ‘O’, 1B and Kaneda, P – are really nice guys and they have accepted us. I have pitchers hollering around camp and Mgr. said he never heard so much life.5

Spring training in 1965 became significant for both Lasorda and US-Japan baseball relations. Because the major leagues were implementing an amateur draft in June, Lasorda as a scout could no longer use his charm and negotiation tactics to sign top prospects, as he did the previous summer with Los Angeles prep star outfielder Willie Crawford. Lasorda drove Crawford to his high-school prom and delivered a stirring eulogy at the funeral of Crawford’s grandfather, a man whom Lasorda had never met.6

At the time of the Lasorda-Myers trip, the status of Japanese pitcher Masanori Murakami remained in limbo after the San Francisco Giants had promoted the lefty from Class A Fresno in September 1964. The Nankai Hawks had sent the 20-year-old Murakami to the United States for minor-league experience in the summer, but his success at Fresno led the Giants to promote him to the majors. San Francisco wanted to keep Murakami, who signed a major-league contract, and the Hawks demanded the return of their prospect. A compromise was finally reached: Murakami would spend one more season in San Francisco and return to Japan in 1966.

After Lasorda’s 1965 Japan trip, which concluded with side trips to Bangkok, New Delhi, Iran, and Tel Aviv, it was back to Dodger Stadium for his next assignment. Scouting director Al Campanis decided Lasorda should become a minor-league manager. His first team produced a 33-33 record at Pocatello, Idaho, of the rookie-level Pioneer League. Lasorda worked his way up the ladder in the Dodger farm system and eventually replaced Walter Alston as Dodgers manager in September 1976.

Life in Southern California would never be the same as Lasorda hugged his players – a stark contrast to Alston’s “Quiet Man” persona – and claimed to “bleed Dodger blue.” Frank Sinatra sang the National Anthem for Lasorda’s first Opening Day in 1977. With a big lead in September, Lasorda sent comedian Don Rickles – wearing a Dodgers uniform and number 40 – to the mound to visit with a suddenly confused reliever, Elias Sosa.

After becoming the first National League skipper to win pennants in his first two years since Gabby Street of the 1930-31 Cardinals, Lasorda was invited to manage a team of National League all-stars against a team of American League stars on a postseason trip to Japan in 1979. In true Lasorda fashion, he motivated his team by privately telling each individual that the Most Valuable Player of the series was going to receive a new automobile. When Cincinnati’s George Foster won MVP honors, he received a bouquet of flowers and a shoulder shrug from his manager. “That’s what I heard,” Lasorda claimed with a straight face.7

Lasorda, though, was disappointed with American League manager Earl Weaver of the Baltimore Orioles. During a controversial play, Weaver argued with umpires and used language the otherwise feisty Lasorda didn’t think appropriate in a goodwill exhibition setting.8

1992 All-Star Baseball Series program (Robert Fitts Collection)

The 1993 trip to Japan was extra-special because Dodgers All-Star catcher Mike Piazza happened to be Lasorda’s godson; his father, Vince Piazza, was a longtime friend from Tommy’s hometown of Norristown, Pennsylvania. A 62nd-round draft choice in 1988, Piazza rewrote the Los Angeles rookie record book in 1993 with 35 home runs, 112 RBIs, and a .318 batting average.

Piazza played a key role in returning the Dodgers to a respectable 81-81 record in 1993 after a 99-loss disaster in 1992 in which the team finished in last place for the first time since 1905. The Dodgers enjoyed knocking the 103-win San Francisco Giants out of the pre-wild-card format postseason with a 12-1 victory on the final day of the regular season as Piazza clubbed two home runs.

Piazza and former World Series pitching star Orel Hershiser were the Dodgers marquee names on the tour. Two other rookies became future stars – pitcher Pedro Martinez, traded by the Dodgers to Montreal weeks after the Japan tour, and Yomiuri Giants outfielder Hideki Matsui.

In addition to baseball, the Dodgers took a tour of Dazaifu, an ancient Japanese regional center, and the Dazaifu Tenmangu Shrine. Lasorda and several Dodger players visited a children’s hospital and passed out Dodger souvenirs and commemorative pins.9

Lasorda provided the photo-op of the tour during batting practice on November 2 by throwing his arms around American sumo star Chad Rowan, who wrestled in Japan under the name Akebono Taro. Earlier in 1993, the 360-pound Rowan made history by becoming the first non-Japanese wrestler to reach Yokozuna status, the highest rank in sumo. Rowan, in town for a wrestling tournament, threw out the ceremonial first pitch.

“The Fukuoka Dome was out of this world,” said first baseman Eric Karros, the 1992 NL Rookie of the Year. “We took a tour before the first game and saw the large training facility and practice areas. There were large mirrors where the Fukuoka players practiced their swings.”10

The Dodgers wore a small black patch with “IKE” in white letters on their uniforms in memory of Akihiro “Ike” Ikuhara, the longtime assistant to Peter O’Malley, who died in October 1992.

Ikuhara joined the Dodgers organization in the spring of 1965 after asking Japanese sportswriter Sotaro Suzuki for an introduction to O’Malley in order to study American baseball. He joined the Dodgers’ Spokane team in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League, where O’Malley was general manager. Ikuhara moved to the Dodgers in 1967. He supervised visits to the United States by the Yomiuri Giants in 1967, 1971, 1975, and 1981, along with the visits of the Samsung Lions of South Korea in 1985 and the Chunichi Dragons of Nagoya, Japan, in 1988. Ikuhara teamed with Nagashima in broadcasting the World Series back to Japan from 1981 to 1986. He was named to the Japan Baseball Hall of Fame in 2002.11

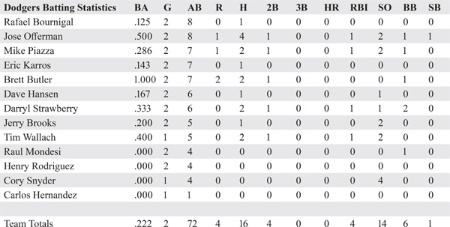

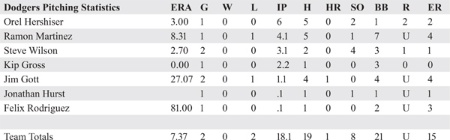

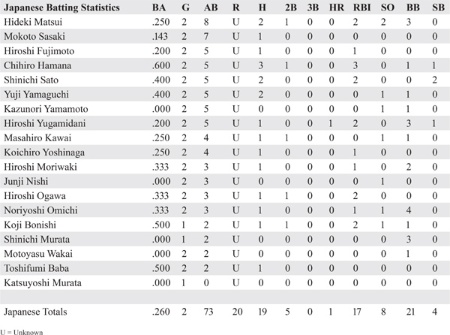

In the series opener, the Dodgers staked Hershiser to a 3-0 lead in the first inning against pitcher Kenichi Wakatabe of the Hawks. Brett Butler reached first on an error. Jose Offerman and Piazza hit consecutive RBI doubles and Tim Wallach drove home Piazza. The Japanese scored twice in the sixth on three hits, including a double over the head of Darryl Strawberry in right field. Chihiro Hamana’s RBI single in the seventh tied the game.12

In the bottom of the 11th inning, number-9 hitter Hiroshi Yugamidani greeted reliever Jim Gott with a line drive to center. Butler tried a shoestring catch, but the ball went past him. A relay throw from shortstop Offerman to backup catcher Jerry Brooks made the play at home plate close, but Yugamidani was ruled safe and gave Japan a 4-3 victory. Yugamidani batted .203 with one home run during the regular season.

Although many Dodgers thought the runner was out at home, Lasorda didn’t protest the call. In the clubhouse, Hershiser took the umpire’s decision in stride because it was an exhibition. Someone asked Lasorda what would have happened if that call was made during a regular-season game. He simply smiled.13

In the second game, on November 3, Dodgers pitching yearned for the airport shuttle while struggling in a 16-1 loss. Were it a spring-training game, the umpires might have offered the teams an early exit. Instead, the capacity crowd of 42,000 watched the combined Fukuoka-Yomiuri squad score nine runs in the fifth inning on four hits and five walks. Overall, the Dodgers pitchers allowed 15 walks and three wild pitches. A leadoff double in the fifth inning by Chihiro Hamana off starter Ramon Martinez triggered the landslide. Relievers Felix Rodriguez and Jonathan Hurst followed Martinez to the mound as five of the fifth-inning walks were with the bases loaded. The Japanese added five runs in the eighth off reliever Jim Gott.14

Hurst, who pitched for the Dodgers’ Triple-A Albuquerque affiliate in 1993 after being claimed on waivers from the Montreal Expos, had been a late addition to the Asia tour roster for bullpen insurance. With veteran Dodgers pitchers Kevin Gross, Tom Candiotti, and Todd Worrell not making the trip, the Dodgers also brought along Rodriguez, who in 1993 converted from catcher to pitcher at Class-A affiliate Vero Beach.

The Dodgers left Asia with a dismal 1-4 record. “I’m disappointed. I’d be lying if I said anything else,” said Lasorda. “When you go a month and then you just throw batting practice, [and] you don’t play in game situations, then it makes a difference.” But “We made these people happy anyway. We made the folks in Taiwan happy and we made the people of Japan happy.”15 “It’s all in fun anyway,” added Darryl Strawberry.16

Lasorda remained the Dodgers manager until the summer of 1996, when a mild heart attack in June led to his retirement. His last full season in the Los Angeles dugout coincided with Nomo’s 1995 arrival – via a minor-league contract because a strike by the Players Association had led to the cancellation of the 1994 World Series and had frozen 40-man rosters during the winter. Nomo attended spring training with Dodgers minor leaguers and was promoted after the strike ended.

Lasorda’s trademark as a manager was providing postgame food in his office, a way to keep communication lines open with his players. Lasorda, who often served Japanese cuisine in Nomo’s honor, recalled his 1965 Japan trip in which Kaneda cooked a four-course dinner for a visiting Dodgers scout.

“Just when baseball had its problems, here comes this young man from Japan with a unique delivery and great ability,” Lasorda said in 1995 as Nomo started the All-Star Game in Texas. “All of a sudden, he’s got the world chasing him and wanting to see him pitch.” Among those watching was Murakami, who became a baseball commentator for NHK after an 18-year pitching career in Japan. Murakami worked many of Nomo’s games at Dodger Stadium and on the road.17

Lasorda was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1997. He came out of retirement at age 72 to coach Team USA in the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, Australia. With O’Malley and Dedeaux in attendance, Lasorda’s team – a collection of minor-league players and veteran major-league catcher Pat Borders – stunned Cuba, 4-0, in the Gold Medal game.

In 2006 Commissioner Bud Selig named Lasorda baseball’s official ambassador for the inaugural World Baseball Classic and did so again in 2009 when the Classic was played at Dodger Stadium. In 2008 Lasorda was honored with the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette, by the Emperor of Japan for his contributions to Japanese baseball. He made countless trips to Japan, serving as a key liaison between the Dodgers and the Orix Buffaloes in their “friendship” agreement.

“It’s amazing to watch Tommy Lasorda go through an airport in Japan,” said Acey Kohrogi, the Dodgers’ director of Asian operations from 1995 to 2013. “Everyone else gets their identification and passport ready to go through security. Tommy just keeps on walking, smiling and waving.”18

Overall, Lasorda visited 28 countries in his lifetime, including Colombia, Denmark, Monaco, Norway, Bermuda, Egypt, Iraq, Turkey, and Afghanistan. He continued to travel during the next two decades, attending his final game at the 2020 World Series in Arlington, Texas, when Los Angeles defeated Tampa Bay at Globe Life Field, a neutral site necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I don’t know if there was a better ambassador to the game than Tommy,” Fred Claire said. “Not because he was a Dodger, but because who he was. The primary reason was his absolute love of the game. It didn’t matter what country Tommy was in. In his own way, Tommy spoke every language. Obviously, he was always good with Spanish. But Tommy had that way of breaking through all barriers to teach, to promote, and talk about the game.”19

MARK LANGILL is the team historian of the Los Angeles Dodgers. A member of the front office since 1994, the Cal State Northridge graduate previously covered the ballclub for the Pasadena Star-News from 1989 to 1993. He has written six books about the Dodgers, including Game of My Life, The Dodgers: From Coast to Coast, and All for One, the official commemorative book of the 2020 World Series champions. His television appearances include the ESPN 30-for-30 documentary Fernando Nation and the History Channel’s American Restoration.

(Click images to enlarge)

Notes

1 Fred Claire, interviews with author, December 2021.

2 Dave Wiggins, “No Rest for O’Malley,” Mainichi Daily News, November 17, 1991: 3.

3 Tommy Lasorda, diary, 1965, author’s collection.

4 Lasorda, diary, 1965.

5 Lasorda, diary, 1965.

6 Lasorda, diary, 1965.

7 Tommy Lasorda, interviews with author, March 2007.

8 Lasorda, diary, 1979.

9 Paul Gomez, “Friendship Tour Bonds Cultures,” Los Angeles Dodgers 1994 Yearbook: 86.

10 Eric Karros, interview with author, November 4, 2021.

11 Mark Langill, “Dodgers Assistant Dies,” Pasadena Star-News, October 27, 1992: 1.

12 Associated Press, “Dodgers Lose Fukuoka Opener 4-3,” Japan Times, November 3, 1993: 20.

13 Lasorda, interviews.

14 Associated Press, “Dodgers Crash 16-1,” Japan Times, November 4, 1993: 20.

15 Brent Johnson, “Famine Follows Flood as Dodgers Fall in Finale,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 5, 1993: 25.

16 Johnson.

17 Mark Langill, “Nomo: A Season to Remember,” Los Angeles Dodgers 1996 Yearbook: 5.

18 Acey Kohrogi, interview with author, May 13, 2019.

19 Claire, interview.

20 These tables include all participants in the series. Nippon Professional Baseball Records, https://www.2689web.com/nb.html.