Twin Cities Ballparks of the 20th Century and Beyond

This article was written by Stew Thornley

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the North Star State (Minnesota, 2012)

Early baseball teams in Minneapolis and St. Paul played in a number of hastily built and short-lived ballparks before settling on a pair that each lasted 60 years, longer than any other park or field used for professional baseball in the Twin Cities.

NICOLLET AND LEXINGTON

Opened and closed a year apart, Nicollet Park in Minneapolis and Lexington Park in St. Paul hosted numerous championship teams and were the hot spots during the major holidays when the Millers and Saints played twin-bills—a morning game at one park and an afternoon game at the other—on Decoration Day, Fourth of July, and Labor Day.

The Minneapolis Millers played in a number of locations, but the ballpark most closely associated with the team was the one described by former Minneapolis Tribune writer Dave Mona as “soggy, foul, rotten, and thoroughly wonderful Nicollet Park.”

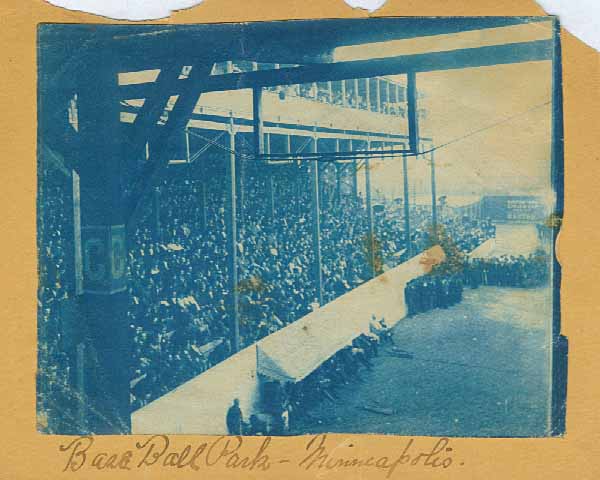

In 1896, Nicollet Park replaced a tiny ballpark in downtown Minneapolis, Athletic Park, and represented a move outside the core area of the city. The location was picked, in part, because of its proximity to public transit, just off the corner of Nicollet Avenue and Lake Street in south Minneapolis.

Although spacious compared to the band box that it had replaced, Nicollet Park soon became known for its modest dimensions, particularly the short distance to the right-field fence, which ran along Nicollet Avenue and was an easy target for strong left-handed hitters. Mike Kelley, who owned the Millers from 1924 to 1946, built his 1930s powerhouse around that fence, pouncing on sinewy southpaw swingers who could bombard Nicollet Avenue beyond. Joe Hauser played for the Millers from 1932 to 1936 and hit 202 home runs during those five years. In 1933, Hauser set a professional baseball record with 69 homers; 50 of them were hit at Nicollet Park. Halsey Hall remembers the right-field fence being made a little higher over the years and awnings going down in front of the plate-glass windows on Nicollet Avenue businesses as insurance rates on window breakage rose.

Although spacious compared to the band box that it had replaced, Nicollet Park soon became known for its modest dimensions, particularly the short distance to the right-field fence, which ran along Nicollet Avenue and was an easy target for strong left-handed hitters. Mike Kelley, who owned the Millers from 1924 to 1946, built his 1930s powerhouse around that fence, pouncing on sinewy southpaw swingers who could bombard Nicollet Avenue beyond. Joe Hauser played for the Millers from 1932 to 1936 and hit 202 home runs during those five years. In 1933, Hauser set a professional baseball record with 69 homers; 50 of them were hit at Nicollet Park. Halsey Hall remembers the right-field fence being made a little higher over the years and awnings going down in front of the plate-glass windows on Nicollet Avenue businesses as insurance rates on window breakage rose.

In 1938 Ted Williams spent his last season in the minors with the Millers. As a 19-year-old in his second season of pro ball, Williams won the American Association Triple Crown, hitting .366 with 43 home runs and 142 RBIs while also leading the league in runs, total bases, and walks. In addition to Williams, some of baseball’s greatest players performed for the Millers at Nicollet Park, including Hall of Famers Willie Mays, Rube Waddell, Ray Dandridge, Monte Irvin, and Hoyt Wilhelm.

Known as a hitters’ park, Nicollet Park witnessed “hits” of different kind in the morning game of the Fourth of July two-game set in 1929. A brawl between the Millers and Saints drew the description of veteran baseball (and boxing) reporter George Barton as “the most vicious affair ever witnessed at Nicollet.” The trouble began in the third inning when Hughie McMullen grounded to Saints first-baseman Oscar Roettger. Pitcher Huck Betts covered first and was spiked by McMullen as he crossed the bag. The St. Paul and Minneapolis newspapers differed the next day as to whether the spiking was intentional, but apparently there was no doubt in Betts’s mind as he took the ball from his glove and fired it at McMullen’s head in retaliation. The throw missed, but Sammy Bohne didn’t. Bohne, a reserve infielder who was coaching first at the time, rushed Betts with a series of punches as the dugouts emptied. McMullen recalled, “Both clubs met in the pitcher’s box and you hit anyone near you.” The headline over Halsey Hall’s story in the Minneapolis Journal the next day read, “Sammy Bohne Doesn’t Play, But Gets More Hits Than Those Who Do.” There were plenty of ejections in the game, but Hugh McMullen was not among the ejectees—ironic because in a letter written by McMullen 55 years later, Hughie admitted that he had indeed spiked Betts intentionally in retaliation for a beanball Betts had thrown a few pitches earlier.

As opposed to a delay for brawling, Sunday doubleheaders were often cut short by a law requiring games to be stopped promptly at 6:00p.m. (The ordinance was repealed in 1941, but Mike Kelley continued to honor the policy.) In 1935 the Millers saw a 3–0 lead disappear as Toledo scored five runs in the top of the ninth. But the clock at Nicollet read 5:54 as the Millers came to bat. With shrewd stalling by Fabian Gaffke, Buzz Arlett, and Joe Hauser, the clock struck six o’clock before the final out was made; as a result, the score reverted back to the last full inning, wiping out the Mud Hen runs and giving the Millers a 3–0 win.

That same season Babe Ruth made a Nicollet Park appearance in a game between the Minneapolis and St. Paul police teams. Ruth played half a game with each team, and contributed a double in five trips to the plate. Pitching for the Minneapolis Police team, Pete Guzy, former East High and Minnesota Gopher pitching sensation and later the longtime football and baseball coach at Edison High, was able to count Babe as one of his 18 strikeout victims in the game.

In 1983 a historical marker was erected in front of the Norwest (now Wells Fargo) Bank on 31st and Nicollet, on the former site of Nicollet Park. The plaque was paid for in large part by donations from ex-players and fans. With their contributions came letters and notes to indicate that memories of Nicollet Park have not faded. Hughie McMullen, who played in the late 1920s, remembers even then Nicollet as a very old, run down park. “The fences were held up only by the paint on them,” says McMullen. Eddie Popowski managed the Millers in their final year at Met Stadium. But as an infielder with Louisville in 1943, he played at Nicollet and recalls players having their gloves and shoes chewed up by rats when they left them overnight. “Nicollet Park holds the best memories in baseball for me,” said Al Worthington. The star of the 1955 playoffs recalls that he had great success at Nicollet Park (his three-year won-loss record at Nicollet was 24–5). Al also remembers the lack of heat in the clubhouse. “It was so cold in April that taking a shower was almost like being outside when the sub-zero wind blew.”

In 1983 a historical marker was erected in front of the Norwest (now Wells Fargo) Bank on 31st and Nicollet, on the former site of Nicollet Park. The plaque was paid for in large part by donations from ex-players and fans. With their contributions came letters and notes to indicate that memories of Nicollet Park have not faded. Hughie McMullen, who played in the late 1920s, remembers even then Nicollet as a very old, run down park. “The fences were held up only by the paint on them,” says McMullen. Eddie Popowski managed the Millers in their final year at Met Stadium. But as an infielder with Louisville in 1943, he played at Nicollet and recalls players having their gloves and shoes chewed up by rats when they left them overnight. “Nicollet Park holds the best memories in baseball for me,” said Al Worthington. The star of the 1955 playoffs recalls that he had great success at Nicollet Park (his three-year won-loss record at Nicollet was 24–5). Al also remembers the lack of heat in the clubhouse. “It was so cold in April that taking a shower was almost like being outside when the sub-zero wind blew.”

* * *

Seven miles to the east of Nicollet Park was its St. Paul counterpart, Lexington Park, which opened in 1897 as home to Charles Comiskey’s Western League team. The team had been playing in a small ballpark on Dale Street, a block south of University Avenue, six days a week, but because of neighborhood opposition was forced to find other venues for Sunday games. One of those sites, a large lot on the southwest corner of Lexington Avenue and University Avenue, approximately one mile west of the Dale Street park and bounded by Dunlap Avenue on the west and Fuller Avenue on the south, became the location for Lexington Park.

Like Nicollet Park, Lexington Park was well removed from the center city when it opened, which became an issue for owner George Lennon when his Saints joined the new American Association in 1902. Because Lennon found Lexington Park too remote, he built a new park on the northern edge of downtown St. Paul. Sunday games were played at Lexington Park, but from 1903 to 1909, the downtown site served as the primary home of the Saints. Starting in 1910, the Saints moved full time at Lexington Park.

Lexington Park had a serious fire in October of 1908, and following the 1915 season an even greater fire destroyed the grandstand. When the park was rebuilt, it was reconfigured, with the diamond turned 90 degrees, moving home plate from the southwest toward the northwest corner of the lot. The ballpark set back 100 feet from University Avenue, which was on the north side of the ballpark, and 100 feet from Lexington Avenue to the east. The main entrance to the grounds was behind home plate, at the corner of University and Dunlap.

With the new configuration came familiar landmarks outside the stadium. The most prominent was the Coliseum Pavilion beyond the left-field fence, its roof being the landing site for many home runs. To the south, behind right field, was Keys Well Drilling, which erected a sign bearing the company name that, although outside the ballpark, was clearly visible to those inside.

This sign wasn’t hit by home runs with the frequency of the Coliseum roof (if the sign ever was hit). In fact, for most of the life of the rebuilt Lexington Park, few balls cleared the right-field fence. The distance down the foul line in right field was 365 feet. A 12-foot-high wooden fence sat atop an embankment that led up to the fence.

Home runs to right field at Lexington Park were so rare as to be memorable. When the New York Yankees came to St. Paul for an exhibition game in June of 1926, the St. Paul Pioneer Press reported that only nine home runs had been hit over the right-field fence since the park had been rebuilt. Bruno Haas was the only player to have done so twice. In 1950, in his only season with the Saints, Lou Limmer, a left-handed hitter, led the American Association in home runs, even though he hit only one at home.

Disaster struck the Twin Cities on Friday, July 20, 1951, as high winds and floods caused millions of dollars in damage. One of the casualties of the gale was the right-field fence at Lexington Park, torn apart by winds reported to have reached 100 miles per hour. The Saints were in Kansas City at the time, giving management a chance to rebuild the barrier before the team returned. By August, when the Saints were back from their road trip, Lexington Park had a new right-field fence, and this one was much closer to home plate. The distance down the line had been shortened to 330 feet. To make it a bit more challenging, a double-decked fence was erected that was 25 feet high, although the embankment that the previous fence had rested atop was gone. Limmer, though, wasn’t around to enjoy new the fences; he had been promoted to the American League.

Lexington Park closed in 1956 and was replaced by a Red Owl grocery store. In 1958 Red Owl imbedded a plaque in the floor of the store to mark the spot of home plate (although it was not exact). Red Owl eventually moved out, but the property remained a supermarket. In the course of changing management, however, the home-plate plaque disappeared. In the summer of 1994, the Halsey Hall Chapter of the Society for American Baseball Research began raising money from former Saints players and fans to erect another marker. In April 1994 a new plaque was mounted on the outside of the structure. When the building was later abandoned the plaque was placed in storage and awaits an appropriate time to be remounted.

MIDWAY AND THE MET

By the middle of the 20th century, it was clear that the Twin Cities’ minor league teams needed new ballparks. Around this same time, the itch for something more was emerging. The transfer of the Boston Braves to Milwaukee in 1953 gave local civic leaders and sports boosters hope that Minnesota could land a major league team, the pursuit of which would require a new ballpark. St. Paul and Minnesota both made plans for stadiums for their existing teams that they hoped would someday house a major league team.

St. Paul settled on a site in the midway area of the city, off Snelling Avenue just south of the State Fair grounds. Midway Stadium opened in 1957 and served the St. Paul Saints for four years. A single-decked stadium, the structure was designed to provide for additional decks if needed for a major league team. When major league baseball finally came, however, the team ended up in the new stadium built for the Minneapolis Millers. The arrival of the major leagues put the Saints and Millers out of business after the 1960 season, leaving Midway Stadium without either its primary tenant or the one it hoped to get.

For the next 20 years, Midway was used for a variety of activities: high-school and other amateur sports, exhibitions such as famed softball pitcher Eddie Feigner with the King and His Court, a practice facility for the Minnesota Vikings football team, and wrestling. Midway Stadium eventually became a drain on the city’s coffers and was frequently referred to as a “white elephant.” It was demolished in 1981, and the city successfully encouraged new office and industrial development on the site.

By the time Midway Stadium opened, the Minneapolis Millers already had a new stadium. Minneapolis business interests raised the money through bond sales for what became known as Metropolitan Stadium, located in Bloomington, a southern suburb. The new ballpark had three decks, which extended only to the end of each of the dugouts. What it didn’t have were posts to support the upper decks; the cantilever construction, rare in sports structures at the time, allowed fans an unobstructed view of the field.

By the time Midway Stadium opened, the Minneapolis Millers already had a new stadium. Minneapolis business interests raised the money through bond sales for what became known as Metropolitan Stadium, located in Bloomington, a southern suburb. The new ballpark had three decks, which extended only to the end of each of the dugouts. What it didn’t have were posts to support the upper decks; the cantilever construction, rare in sports structures at the time, allowed fans an unobstructed view of the field.

The Millers played at Met Stadium from 1956 through 1960. The announcement near the end of October 1960 that Washington Senators owner Calvin Griffith was moving his team to Minnesota culminated the state’s quest for major league baseball. The incoming Twins would play at Met Stadium, which would be expanded. The first two decks were extended down the right-field line although the grandstand on the third-base line was never extended.

Bleachers filled the gap down the left-field line, with wooden bleachers providing seating beyond the outfield fences. Eventually, a double-decked grandstand was built in left field for the Minnesota Vikings, the National Football League team that shared the stadium. In addition to the Twins and Vikings, the Met hosted the Minnesota Kicks soccer team as well as events ranging from wrestling matches to a Beat1es concert.

The Met was primarily a baseball stadium, and it didn’t work well for football. Even with the new grandstand, which provided more seats between the goal lines, spectators on both sides of the gridiron were far removed from the game. The Vikings were the first of the stadium’s tenants to seek a new home, starting in the early 1970s.

Weather was an ongoing challenge, and games were sometimes postponed or delayed because of rain, snow, and at least once by a nearby tornado touchdown. One delay occurred for a completely different reason. In the fourth inning of a game versus the Boston Red Sox on August 25, 1970, first-base umpire Nestor Chylak ran in toward the infield, waving his arms to call time. The interruption was explained with an announcement that the Bloomington police had been told an explosion would take place at Met Stadium at 9:30. The week before, the Old Federal Building in downtown Minneapolis had been bombed, and officials were taking no chances, although they allowed the game to start and be played until 9:15, approximately 45 minutes after the threat had been called in. The players congregated on the field, away from the stadium structure itself, and the fans were directed to the parking lots. Many of the fans, however, found their way onto the field where they mingled with the players and got autographs, while vendors worked the crowd, hawking concessions. Few people even noticed the time when the scoreboard clock showed 9:30, the time set for the explosion, which never occurred. Twenty minutes later, fans re-entered the stadium and cleared the field, and the game resumed shortly before 10:00. The only blast of the night was from Boston’s Tony Conigliaro, who homered in the eighth inning to give the Red Sox a 1–0 victory.

Harmon Killebrew provided the most frequent blasts, hitting many of his 573 career home runs at the Met. Two of the longest came on the first weekend of June in 1967. On Saturday, June 3, Killebrew homered into the upper deck in left. The estimated distance of the drive was 430 feet. (Met Stadium had been one of the first stadiums to measure homers, the result of a table used to record the distance to each section and row of the outfield seats; the measurements given were to the point of impact, not the estimated distance of how far the ball would have traveled had there been no obstructions.) The next day the Twins announced that the estimated distance it would have traveled was 520 feet. This announcement had barely been made when Killebrew connected again, hitting a shot off the facing of the second deck, farther toward left-center field. The estimated distance it would have traveled was given as 550 feet although the point of impact was measured at 434 feet.

Metropolitan Stadium’s biggest year was 1965, when it hosted both the All-Star Game and the World Series. The crowd at Metropolitan Stadium for the first game of the Series included a man from Illinois, Ralph Belcore. A veteran of 21 World Series, the 60-year-old Belcore had arrived at Met Stadium at 7:30 the morning of Sunday, September 26 to stake out the first spot in the ticket line for general admission seats, even though this left him with a wait of more than 245 hours before the first game. The Twins lost the World Series to the Los Angeles Dodgers, four games to three, with more than 50,000 fans present for the decisive seventh game, the only time the Twins topped 50,000 in a game at Met Stadium.

Metropolitan Stadium’s biggest year was 1965, when it hosted both the All-Star Game and the World Series. The crowd at Metropolitan Stadium for the first game of the Series included a man from Illinois, Ralph Belcore. A veteran of 21 World Series, the 60-year-old Belcore had arrived at Met Stadium at 7:30 the morning of Sunday, September 26 to stake out the first spot in the ticket line for general admission seats, even though this left him with a wait of more than 245 hours before the first game. The Twins lost the World Series to the Los Angeles Dodgers, four games to three, with more than 50,000 fans present for the decisive seventh game, the only time the Twins topped 50,000 in a game at Met Stadium.

The Twins were successful during their first decade in Minnesota. Their attendance topped 1,000,000 (then considered a benchmark for success) in each of their first 10 years at the Met, and they twice led the league in attendance. In total, over this decade the Twins led the American League in attendance. As the team dropped in the standings during the 1970s, however, so did attendance. The Twins joined the Vikings in seeking either a new stadium or significant improvements to the existing one and eventually were successful.

The Twins played their last baseball game at Met Stadium on September 30, 1981, losing to the Kansas City Royals. The final event at the Met was a Vikings game against the Kansas City Chiefs on Sunday, December 20, 1981. Following the game, fans in search of souvenirs ravaged the stadium, taking what wasn’t bolted down as well as many things that were.

Met Stadium remained partially dismantled for several years before being totally demolished, and it remained a vacant site for several more years before a large shopping center, dubbed the Mall of America, was erected on the site. A plaque marking the spot of home plate was installed in an amusement-park area in the middle of the shopping center.

HUBERT H. HUMPHREY METRODOME

The Minnesota Legislature passed a non-site specific stadium bill in 1977 and empowered a newly created stadium commission to evaluate options. In late 1978 the commission voted to erect a multi-purpose covered facility on the eastern edge of downtown Minneapolis, and the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome opened in 1982 with 55,000 seats available for baseball. The capacity for football—both the Vikings and the Minnesota Gophers, who abandoned Memorial Stadium on the University campus to play in the new domed facility—was 8,000 more than for baseball.

The Minnesota Legislature passed a non-site specific stadium bill in 1977 and empowered a newly created stadium commission to evaluate options. In late 1978 the commission voted to erect a multi-purpose covered facility on the eastern edge of downtown Minneapolis, and the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome opened in 1982 with 55,000 seats available for baseball. The capacity for football—both the Vikings and the Minnesota Gophers, who abandoned Memorial Stadium on the University campus to play in the new domed facility—was 8,000 more than for baseball.

The first event was an exhibition baseball game between the Twins and Philadelphia Phillies on Saturday night, April 3. The temperature outside was 19 degrees, made colder by northwesterly winds of 30 miles per hour with gusts up to 45. Pete Redfern threw the first pitch for the Twins and the second batter up for the Phillies, Pete Rose, got the first hit. Kent Hrbek of the Twins hit the first two home runs in the new stadium. Three nights later, the first regular-season game was played, with the Twins losing to the Seattle Mariners. With two out in the bottom of the first, Minnesota’s Dave Engle put one over the left-field fence for the first official hit and home run in the Metrodome.

The Metrodome was functional but short on amenities. The sterile nature of the stadium was not conducive to the aesthetic atmosphere desired by many fans. Other problems included the roof, which caused players to lose sight of fly balls. The first inside-the-park home run at the Metrodome came on Friday night, May 28, 1982, when Tom Brunansky hit a high fly to left. Yankees left fielder Lou Piniella stood helplessly, his arms outstretched, as he couldn’t see the ball, which dropped to the ground and stayed in play by bouncing off the fence as Brunansky circled the bases. One ball that got lost in the roof in a more literal sense was hit on May 4, 1984, by Dave Kingman of Oakland, a pop up that didn’t come down. The ball went through a vent hole in the roof, and, by the ground rules of the Metrodome, Kingman was awarded a double.

The artificial turf initially installed in the Metro-dome was extremely spongy, causing high bounces that played havoc with fielders. White Sox right fielder Harold Baines suffered a related problem on Sunday, June 24, 1984. The Twins were trailing 2–0 with two on and one out in the last of the ninth when Tim Teufel dropped a hit into right field. Baines charged in to field the ball, which hit a seam in the turf, bounced over his head, and rolled to the fence. Teufel ended up with a game-winning, three-run inside-the-park home run. Different types of artificial turf have been installed since then, generally correcting the problem.

Although the roof insulated the Twins from weather problems, one game was postponed after a storm, which began the evening of Wednesday, April 13, 1983, and dumped 131?2 inches of wet, heavy snow on the Twin Cities. The California Angels, scheduled to play the Twins on Thursday night, had taken an overnight flight from California and arrived over the Twin Cities at about 5:30 on Thursday morning. The plane, however, was unable to land and diverted to Chicago, where the Angels spent the day. The absence of the Angels, combined with concerns for the safety of players and fans trying to get to the Metrodome that night, prompted the Twins to postpone the game. That night, a chunk of ice tore a 20-foot gap in the roof of the Metrodome, causing it to deflate. The roof collapse is often given as the reason for the postponement, but in fact, the game had already been postponed nearly 12 hours earlier. On a side note, a roof collapse on the Metrodome in 2010 did cause a Minnesota Vikings game to be moved. The game, scheduled against the New York Giants for noon on Sunday, December 12, was first postponed until Monday night after the Giants’ flight on Saturday was diverted to Kansas City. When the roof collapsed and tore later in the day, it became uncertain when the stadium would be available again, and the National Football League moved the game to Detroit. The Metrodome was still out of service the following week, so the Vikings played their final home game of the season at TCF Bank Stadium at the University of Minnesota.

A roof breach that did affect a game occurred on Saturday night, April 26, 1986. In the eighth inning, a storm ripped a hole in the roof, soaking fans in the upper deck in right field as water poured through. High winds also caused the light bars to sway and the game was delayed as fans were evacuated from the seating area. The game was eventually resumed, but the Twins may have wished it wasn’t as the California Angels scored six runs in the ninth inning, capped by a two-out, two-run home run by Wally Joyner off Ron Davis, to win 7–6. In the end, despite its many complaints and flaws, the Metrodome’s tenure as the home of the Twins and Vikings exceeded that of Met Stadium.

As part of the authorizing stadium legislation, the Twins and Vikings had been required to sign 30-year leases. However, Twins owner Calvin Griffith insisted on an escape clause, which could be triggered if, among other things, the Twins did not average at lease 1.4 million fans per year over three consecutive years. It also required the installation of air conditioning if the lack of it affected attendance. Although the duct work was in place, the stadium opened without air conditioning, and the Metrodome climate was oppressive during the first summer. Air conditioning was installed and was first used in June of 1983.

Even with the cooler temperatures in the Metro-dome, drawing fans was a problem, mainly because of the poor performance by the Twins. Despite a number of players who would later become stars, in 1982 the Twins lost more than 100 games and attendance was only 921,186. In 1983, the Twins were 70–92 and it was becoming clear that attendance would probably not achieve the average of 1.4 million per season through 1984, allowing Griffith to terminate the lease.

In response the local business community began buying unused tickets to the games. The plan was to buy the least expensive tickets, which meant focusing on the weekday games when ticket prices were discounted. The first occurrence of a buyout was on Tuesday night, May 15, 1984, when the Twins played the Toronto Blue Jays. Although fewer than 10,000 fans attended the game, the paid attendance was 26,761. The next day, with discounted prices in effect, the paid attendance was 51,863, although the number of fans present was closer to 8,700 (with more than 2,300 of those being school-patrol members who got in free, leaving the turnstile count for paid ticket holders at 6,346). The Twins began announcing two attendance figures for games based on tickets sold and on the turnstile count. A legal battle loomed as to whether this artificial padding of attendance would actually stop Griffith from exercising his escape clause; instead, in June of 1984, Griffith signed a letter of intent to sell the Twins to banker and Pepsi bottling magnate Carl Pohlad.

Despite the new ownership, concerns over the lack of stadium revenues prompted the Twins to seek a new stadium in the latter part of the 1990s. The drawn out negotiations revealed that additional escape clauses in varying forms remained, and the threat for the team to leave (either by relocation or by being entirely eliminated, an issue that surfaced after the 2001 season) resurfaced.

As construction was in its final stages for a new Twins’ stadium at the other end of downtown Minneapolis, major league baseball at the Metrodome featured a set of reprieves in October 2009. The Twins’ final scheduled game of the season was at home, against Kansas City, on Sunday, October 4. Only three weeks before that, Minnesota was 51?2 games behind first-place Detroit. However, the Twins won 11 of their next 12 and were back in the race. On October 4 Minnesota beat Kansas City 13–4 to tie the Tigers for first place, meaning at least one more game in the Metrodome. Two days later, Minnesota hosted a tiebreaker game against Detroit, an exciting back-and-forth contest that ended with a 6–5 win for the Twins in 12 innings.

The Metrodome lived on but faced another possible final game on Sunday, October 11. The Twins had dropped the first two games of their best-of-five playoff series against the Yankees in New York. In Game Three at the Metrodome, Minnesota carried a 1–0 lead into the seventh, but home runs by Alex Rodriguez and Jorge Posada (the latter one the last ever hit in a major league game in the stadium) sent the Yankees on to a 4–1 win, eliminating the Twins and ending their 28-season tenure in the Metrodome.

TARGET FIELD

Although the Metrodome was expected to serve the Twins for at least 30 years, by the mid-1990s the Twins were pushing for a new home. In 1997 owner Carl Pohlad unsuccessfully sought public funding for a new park, one with a retractable roof on a site along the Mississippi River, a few blocks from the Metrodome. The proposal turned into a public-relations disaster when what appeared to be the offer of a significant contribution by the Twins turned out to be more along the lines of a loan; in addition, the threat of a move by the Twins to North Carolina hung over the issue and turned off some fans. The level of distrust intensified after a book, Stadium Games by Society for American Baseball Research member Jay Weiner, suggested that the proposed ownership group in North Carolina was put in place more for the purpose of giving the Twins and Minnesota stadium proponents additional leverage than it was to present a serious offer to purchase and move the team.

Although the Metrodome was expected to serve the Twins for at least 30 years, by the mid-1990s the Twins were pushing for a new home. In 1997 owner Carl Pohlad unsuccessfully sought public funding for a new park, one with a retractable roof on a site along the Mississippi River, a few blocks from the Metrodome. The proposal turned into a public-relations disaster when what appeared to be the offer of a significant contribution by the Twins turned out to be more along the lines of a loan; in addition, the threat of a move by the Twins to North Carolina hung over the issue and turned off some fans. The level of distrust intensified after a book, Stadium Games by Society for American Baseball Research member Jay Weiner, suggested that the proposed ownership group in North Carolina was put in place more for the purpose of giving the Twins and Minnesota stadium proponents additional leverage than it was to present a serious offer to purchase and move the team.

Pohlad’s talk of moving the Twins, combined with the illusory nature of the “contribution” to a new ballpark, turned the man once seen as the savior of the franchise when he purchased it in 1984 into a villain. Pohlad’s popularity plummeted further a few years later when it was reported that he had volunteered the Twins as one of the two teams to be contracted in exchange for a large sum of money—reported to be anywhere from $150 million to $250 million—from Major League Baseball.

Baseball Commissioner Bud Selig faced many obstacles in carrying out his team-trimming, and one of the first hurdles tripped him up. The Metropolitan Sports Facilities Commission filed suit to compel the Twins to honor their lease at the Metrodome. On November 16, 2001, only 10 days after the vote by the owners for contraction, Hennepin County District Judge Harry Crump granted an injunction that prohibited the Twins from taking any action that would prevent them from playing in the Metrodome in 2002. The Minnesota Court of Appeals upheld the injunction in January, and the state Supreme Court the following month refused to hear the case. It is unlikely that contraction would have occurred even if the injunction had not been granted, but the court actions signaled the end of any hope Selig had for getting rid of two teams in 2002. Meanwhile the city of St. Paul had gotten into the act, making an attempt to lure the Twins from Minneapolis, but this effort died when St. Paul voters rejected a referendum to raise their sales tax to fund a new stadium.

By the time most of the controversy from these actions dissipated, another push began. In 2005 the Twins and Hennepin County, which encompasses Minneapolis, reached agreement on a package to fund a new ballpark. However, approval from the Minnesota Legislature was needed to allow the county to raise its sales tax without a county-wide referendum, and the Legislature adjourned its 2005 session without final action on a ballpark bill.

Finally in 2006, the state legislation was approved and that summer the Hennepin County Board of Commissioners authorized a .15 percent sales tax to partially fund a new ballpark. The site was on the northwestern edge of Minneapolis’s downtown, just over one mile from the Metrodome and one block beyond Target Center, the arena that houses the NBA’s Minnesota Timberwolves. (Eventually the naming rights for the Twins’ stadium were sold to Target Corporation, which already held the rights to the name of the basketball arena, and the new ballpark is called “Target Field.”)

The plan called for an open-air stadium with no provisions for a retractable roof. Money for a roof wasn’t available, and constraints on the eight-acre site do not allow for a movable roof to be added in the future. The site for the ballpark was being used as a parking lot and is located between two elevated roads: Fifth Street North to the northeast (beyond what would be the left-field stands) and Seventh Street North to the southwest (behind first base). To the northeast, behind third base, is the Hennepin Energy Recovery Center, a waste-to-energy facility commonly known as the “garbage burner.” Interstate 394, to the southeast beyond right field, separates the site from Target Center, although a parking ramp is over the freeway and eventually a plaza was built over I-394 to allow better access to the ballpark. In addition, a light-rail line was extended a few blocks to get to Target Field, where it connects with commuter rail that runs to the northern and northwest suburbs and beyond. With the new site, in a small way baseball in Minnesota returned to its past; only a block away from the center field entrance was the left-field corner of Athletic Park, home to the Minneapolis Millers from 1889 to 1896.

A ceremonial groundbreaking scheduled for early August 2007 was postponed for several weeks following the collapse of the I-35W bridge over the Mississippi River. Construction progressed over the next two-and-a-half years. Much of the erecting was done from the inside out with cranes on the site of the field hoisting exterior panels and other materials over the top of the emerging structure.

Target Field includes many features and amenities, including a range of dining options, that had not been present in the Twins’ previous homes. In addition, the Twins decided to use the high-profile nature of their new ballpark to highlight issues of sustainability. The ballpark includes a membrane filtration system to capture and treat rainwater for use in irrigating the field and washing the grandstand. Besides reducing municipal water usage by more than 50 percent, saving more than 2 million gallons of water each year, the arrangement brings attention to the global issue of water, raising awareness of the value of sustainability and the wise use of water.

The first event in Target Field was a college baseball game between the Minnesota Gophers and Louisiana Tech Bulldogs on Saturday, March 27, 2010. Clint Ewing of the Bulldogs hit the first home run in the park as Louisiana Tech beat Minnesota 9–1. Approximately 35,000 people passed through on the first day with fans watching the game while also checking out the features of the new digs.

The following weekend the Twins hosted a pair of exhibition games, both in front of sellout crowds, against the St. Louis Cardinals. Denard Span of Minnesota hit the first major league home run in Target Field during a win by the Cardinals on Friday, April 2.

The Twins went on the road to open the regular season and returned for a homestand, starting against the Boston Red Sox, on Monday, April 12. Under partly-cloudy skies with a temperature of 65 degrees, Minnesota’s Carl Pavano delivered the first pitch at 3:13p.m., officially bringing outdoor major league baseball back to Minnesota. The Twins won the game 5–2 with Jason Kubel of Minnesota hitting the only home run, a drive to right leading off the last of the seventh. Two innings earlier, Boston’s Mike Cameron hit a long fly to left that disappeared in a narrow gap between the foul pole and a limestone wall. Third-base umpire Kerwin Danley ruled the ball foul, but the umpires conferred and decided to use video replay to confirm the call. Danley’s foul ruling was upheld, and Cameron struck out on the next pitch. Video replay became a relatively common occurrence at Target Field during its first year; it was used eight times (with two calls being overturned and six upheld) in 2010, setting a record for the most uses of replay in a season at one stadium.

In its first season, Target Field demonstrated itself to be a pitchers’ park as it was below average in runs scored and last in home runs. Joe Mauer, after hitting 28 home runs in 2009 (16 in the Metrodome), hit only 9 in 2010, 1 at home. On the other hand, the Twins’ Jim Thome hit 15 of his team-high 25 home runs at Target Field in 2010, including a Labor Day blast off the top of the flag pole in right that was measured at 480 feet.

In 2011 the Twins added a video board above the stands in right field so that fans in left field could see it as well as a 100-foot-high tower in right field for animation and graphics. The top of the tower displays the time.

The Twins also made some changes to help their hitters, some of whom had complained about the surface of the center-field batters’ eye as well as the spruce trees in front of the batters’ eye. The hitters said they had trouble “locking in” on pitches with the trees swaying in the wind, so the 14 trees were removed. Nevertheless, the park continued to play to the benefit of the pitchers, particularly by depressing home runs for left-handed batters. In 2010 Target Field had a run index of 96, meaning it depressed runs by 4 percent relative to a neutral park; in 2011 the run index actually declined slightly to 94. The home run index for left-handed batters was only 65 and 72 respectively for the two seasons.

The opening of Target Field began another chapter in Minnesota baseball. Metropolitan Stadium was a workable stadium for major league baseball. With its often described erector-set construction, the Met didn’t have the character of ballparks from the classic era of stadium design. However, it has become the symbol of nostalgia and happy memories for many who grew up with it. The Metrodome was functional—it could be converted to handle baseball and football, not to mention a wide range of other sports and activities—but completely without charm. It ensured games would be played as scheduled and protected fans from rain, cold, and sometimes snow, but it also shielded them from the sun and pleasant days and nights that are a common, if not constant, part of Minnesota summers. Target Field was built amid the period of retro-ballparks, facilities built for baseball only along with distinctive features for an old-feel look and modern amenities. Many fans embraced the idea of a smaller stadium for a seemingly more intimate feel and have had to face the realities of having a harder time getting tickets. Limiting supply, owners have found, has a way of creating and maintaining demand and, Target Field proved a popular destination for fans during its first season. Out of 85 games (including two exhibition and two playoff games), all but two were sold out, and the Twins had a regular-season attendance of 3,223,640. The fortunes of the Twins will no doubt influence the demand in the future, but the new ballpark clearly appears to have brought a new look and feel to the game and re-energized baseball fans in Minnesota.

STEW THORNLEY is an author of books on sports history for adults and young readers. He received the SABR-Macmillan Baseball Research Award in 1988 for his first book, “On to Nicollet: The Glory and Fame of the Minneapolis Millers.” He also enjoys visiting graves of notable people and is the author of “Six Feet Under: A Graveyard Guide to Minnesota.” Stew is an official scorer for Minnesota Twins home games and also does the datacasting of games for MLB.com Gameday. He lives in Roseville, Minnesota, with his wife, Brenda Himrich, and their cats, Jeter and Mickey.