Ty Cobb, Joe Jackson and Applied Psychology

This article was written by David Shoebotham

This article was published in 1985 Baseball Research Journal

With the 1911 season about finished, Shoeless Joe Jackson of Cleveland topped me nine points in the averages … Jackson was … a friendly, simple, and gullible sort of fellow. On the field, he never failed to greet me with a “Hiyuh, brother Ty!”

So now we were in Cleveland for a season-closing six-game series, and before the first game I waited in the clubhouse until Jackson had taken his batting practice …. Ambling over, Joe gave me a grip and said, “How’s it goin’, brother Ty? How you been?”

I stared coldly at a point six inches over his head. Joe waited for an answer. The grin slowly faded from his face to be replaced by puzzlement.

“Gosh, Ty, what’s the matter with you?”

I turned and walked away. Jackson followed, still trying to learn why I’d ignored him.

“Get away from me!” I snarled.

Every inning afterward I arranged to pass close by him, each time giving him the deep freeze. For a while, Joe kept asking, “What’s wrong, Ty?” I never answered him. Finally, he quit speaking and just looked at me with hurt in his eyes.

My mind was centered on just one thing: getting all the base hits I could muster. Joe Jackson’s mind was on many other things. . . . We Tigers were leaving town, but I had to keep my psychological ploy going to keep Jackson upset the rest of the way.

So, after the last man was out, I walked up, gave him a broad smile and yodeled, “Why, hello, Joe – how’s your good health?” I slapped his back and complimented him on his fine season’s work.

Joe’s mouth was open when I left.

Final standings: Cobb .420 batting mark, Jackson, .408.

It helps if you help them beat themselves.

— From “My Life in Baseball: The True Record,” by Ty Cobb with Al Stumpf

*****

TY COBB PSYCHING OUT JOE JACKSON to win the 1911 American League batting championship is one of baseball’s most memorable anecdotes. There are many versions of the story, varying in details, but all agree on the basic plot. There’s only one problem with the story: It never happened.

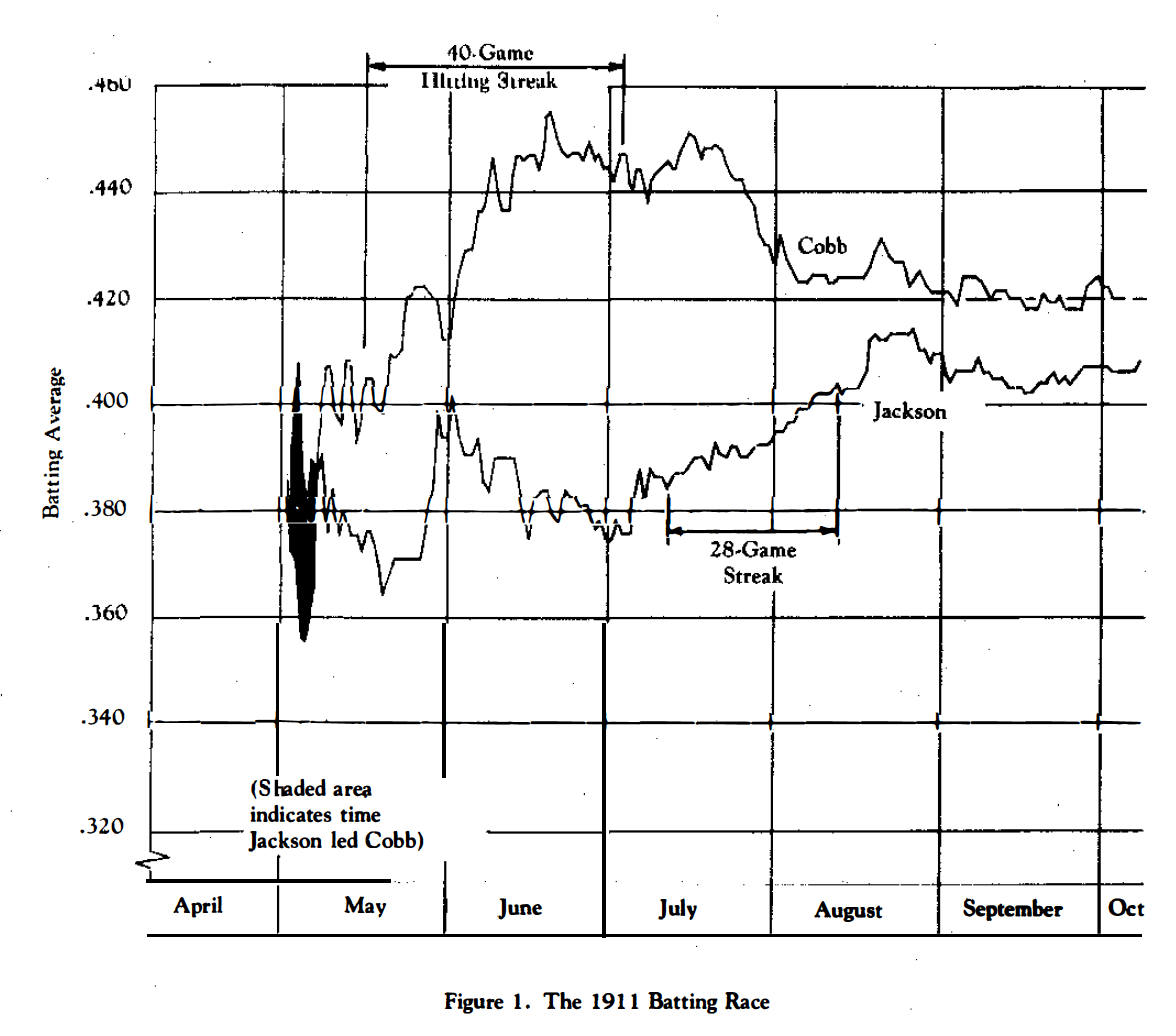

A glance at Figure 1 on the 1911 batting race shows why. The day-by-day records of that season reveal that Cobb passed Jackson on May 7 and never again fell behind. From May 15 to July 2 Cobb hit .482 while putting together a 40-game hitting streak – an American League record at the time – and raising his average to . 44 7. At the same time Jackson was hitting a very respectable .378, which nevertheless left him 69 points behind.

Jackson picked up his pace in July, running up a 28-game streak between July 11 and August 12. Jackson’s average climbed over .400 on August 8, and the gap narrowed to 22 points. By August 25 Jackson was only nine points behind Cobb, but he never came any closer.

To salvage the legend, one could assume that rather than having come from behind Cobb used his psychological ploy to derail the onrushing Jackson and preserve his narrow lead in the batting race. But even this interpretation doesn’t stand up. Detroit and Cleveland played their last three games against each other on October 2 and 4 in Cleveland. Going into this series Cobb had a 15-point lead in the batting race (.422 to .407). The possibility of Jackson overtaking Cobb’s lead at that late date could not have been very great, and Cobb had no need to apply psychological pressure.

The only other time Cobb and Jackson met during the last three months of 1911 was for a single exciting game in Detroit on September 10, the kind of game that produced the Cobb legend. The Georgia Peach singled in the first inning but was stranded. after stealing second and third. Cleveland scored the game’s first run in the seventh when Nap Lajoie doubled home Jackson. Detroit tied it with two away in the eighth; Cobb beat out an infield hit, continued to second when the late throw to first base was high and streaked for third when the pitcher, after retrieving the ball, threw to second. When the Cleveland second baseman threw wildly to third, Cobb tore home and slid around the catcher, scoring on his own infield hit. Cobb beat out another infield hit in the thirteenth inning and was on second base, with the bases loaded, when Detroit scored the winning run on an error.

At that point Cobb’s lead over Jackson was 14 points (.420 to .406). With one month remaining in the season the possibility that Jackson might overtake Cobb was considerably better than it would be on October 2. However, if Cobb snubbed Jackson on September 10, it certainly didn’t work. From then to the end of the season Cobb hit .422, hardly the pace of a psyched-up demon. Over the same period Jackson hit .420, hardly the dramatic decline of a befuddled bumpkin.

So the whole story could be a myth, a tale fashioned out of Cobb’s megalomania to embroider his already larger-than-life legend.

Or is it?

After all, 1911 wasn’t the only year that Jackson finished close behind Cobb in the batting race. They also were 1-2 in 1912 and 1913. Maybe one of those years provides support for the story.

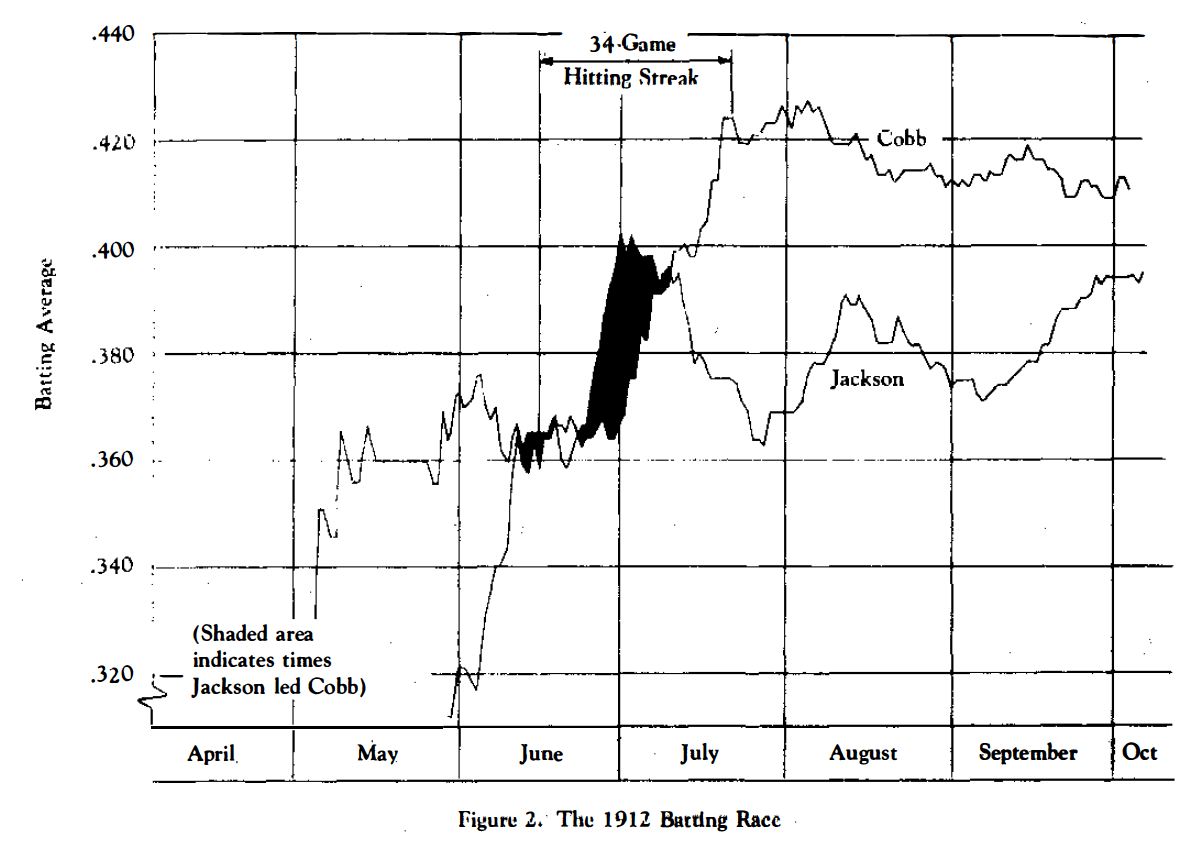

BUT AS SHOWN IN Figure 2, the 1912 season looks no more promising as support for the legend than 1911. Jackson started slowly, but in June he hit a blistering .529, raising his average from .308 to .404. As hot as Jackson was in June, Cobb was even hotter in July. He hit .535 for the month, passed the slumping Jackson on July 10 and kept the lead for the remainder of the season.

As part of his July binge, Cobb challenged his own year-old record by compiling a 34-game hitting streak, which was snapped when he went 0-for-4 against Walter Johnson on July 22. That was the only game between June 16 and August 7 in which Cobb didn’t get a hit, and thus he barely missed a 50-game streak which could have made life a little more difficult for Joe DiMaggio 29 years later.

The next-to-last Detroit-Cleveland series of 1912 was played on July 1-2-3. Starting with that series, Cobb went on his July tear and Jackson fell into a slump. While at first glance this period might appear to have been the setting of Cobb’s legendary trick, it seems to be much too early in the season to be a realistic candidate. Even if Cobb had had the idea that early, it seems reasonable that he would have saved it for a more propitious occasion. The only other time that 1912 might have been an appropriate setting for Cobb’s ploy was during the Detroit-Cleveland series of September 24 (in Detroit) and September 26-29 (in Cleveland). But Cobb went into that series with a 21-point lead, and again it was clearly too late for Jackson to challenge him. So the 1912 records do not support Cobb’s story.

A look at 1913, however, provides an entirely different – and more promising – picture. In fact, 1913 fulfills all of the important conditions of Cobb’s story except the specific reference to 1911.

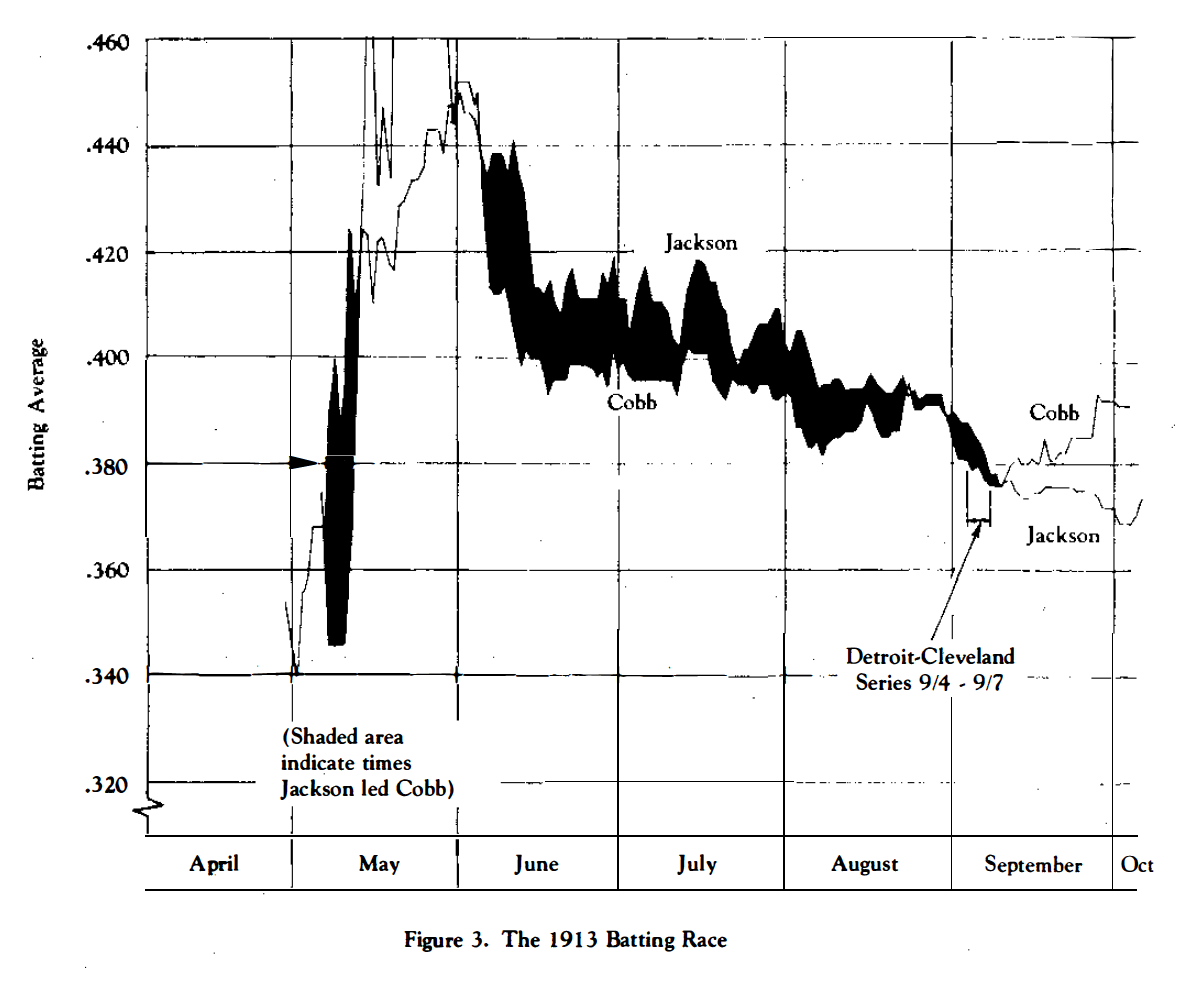

Figure 3 reveals that both Cobb and Jackson started the ’13 season with hot bats. Jackson even had another of those .500 months, hitting .505 in May. Cobb missed the first few weeks of the season because he was holding out, but once he was back in the Tiger lineup he made opposing pitchers wish he had never settled. As June opened Cobb was batting .452 and Jackson .450.

Both hitters gradually declined from those early peaks. But Jackson was the batting leader all through the summer. Except for August 23 and 30 Jackson led every day from June 5 through September 8-or 94 of 96 days. This prolonged period in which he was overshadowed by his principal batting rival must have been infinitely irritating to Cobb, who by this time had come to regard the batting championship as something of a personal possession. It must have been particularly galling to Cobb that, with Jackson’s average slipping, he was missing good opportunities to take the lead. As the Tigers pulled into Cleveland for the start of a four-game series on September 4, it can be assumed that a brooding Cobb, still trailing Jackson by seven points, was prepared to take extreme measures to change the situation.

AND CHANGE IT DID. Cobb did not hit particularly well during the Cleveland series ( which shifted to Detroit on September 6), but he hit a furious .450 the remainder of the way to raise his average from .381 to .390. On the other hand Jackson skidded into a miserable slump. From September 4 to October 1 he hit only . 256 (compared to .365 during the previous month) as his average slipped from .388 to .369. During and just after the Detroit series he was at his worst, hitting only .194 over a ten-game stretch. Jackson no doubt gained some satisfaction by going 5-for-6 in his final two games (October 4-5) and raising his season mark to .3 73, but by then the batting championship had been irretrievably lost.

But the question remains: Did Ty Cobb really snub Joe Jackson and thereby win a batting championship? The answer to that question must not only consider the facts, but must also take into account that establishing a cause-and-effect relationship in this kind of a situation is difficult if not impossible. There might have been, after all, other reasons for Cobb’s late surge and Jackson’s late slump in 1913. What can be said, however, is that if Cobb did snub Jackson, he did it not in 1911 but during that four-game series in early September 1913, and that the results appear to have been as effective as he claimed.