Tyrus: A Study and Commentary on Ty Cobb’s First Name

This article was written by William R. Cobb

This article was published in Fall 2023 Baseball Research Journal

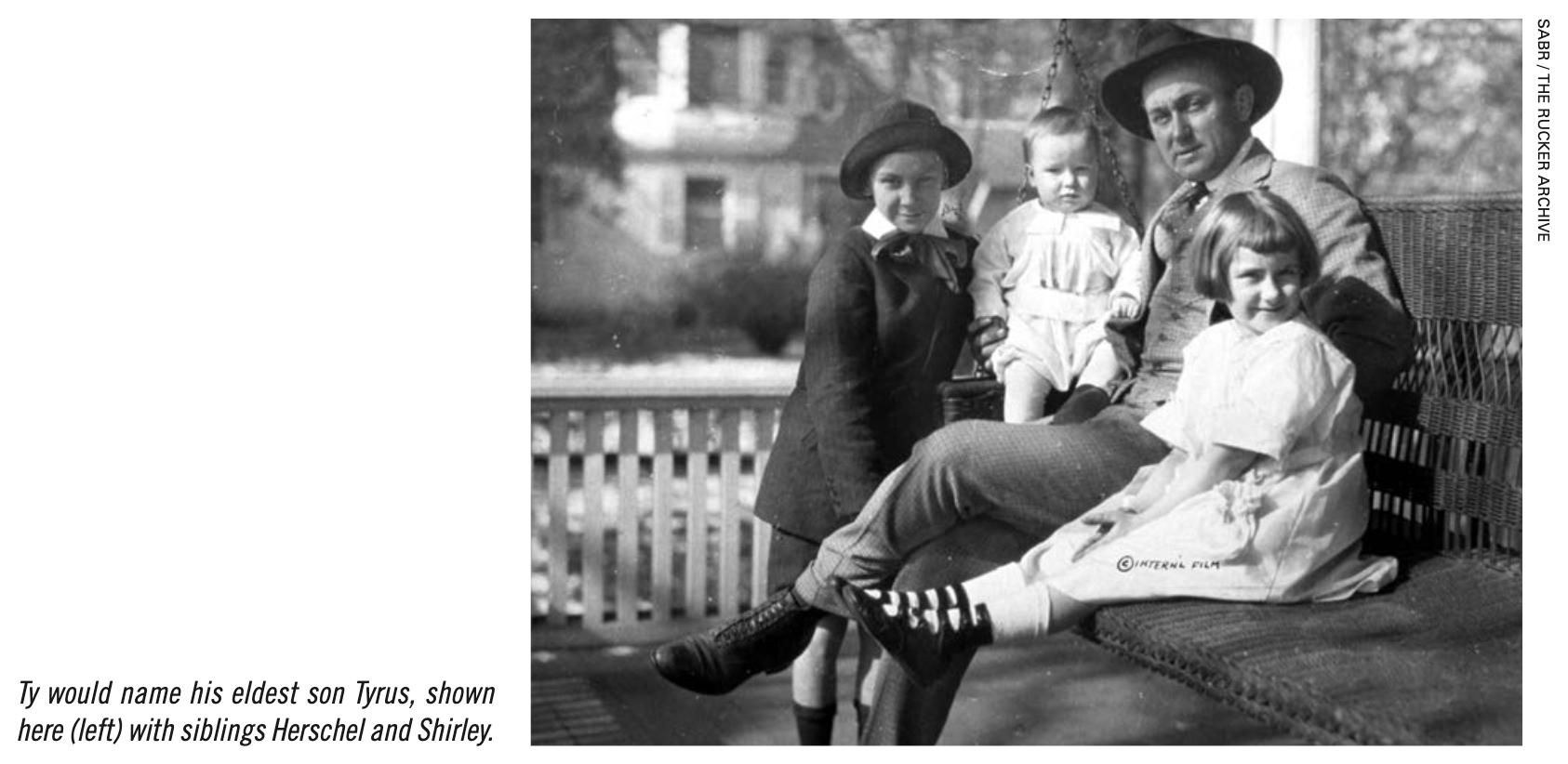

In 1904 when Tyrus Raymond Cobb arrived on the professional baseball scene, his first name was not at all well known. In fact, most fans had never even heard of anyone with that particular name—Ty himself apparently among them. That was to change in short order, however, as Tyrus Cobb’s fame spread nationally within a few short seasons. As Ty’s fame grew, so did the population with the name Tyrus, as many admiring fans gave that name to their newborns in honor of the rising star.

Today, every modern-day baseball fan knows the name. But many, if not most, fans believe the name to have been unique to Ty Cobb. Most Cobb biographers have felt the need to explain where this unique name came from—a testament to its uniqueness. Baseball fans, they reason, would want to know why Ty’s parents gave him such an uncommon name and how they arrived at their choice. But over the course of Ty’s much-documented life and career, multiple conflicting stories about his name have been told and retold. By examining the writings of Ty’s biographers and of Ty himself, and reviewing relevant ancient and modern historical sources, this paper will delve into these myths, debunk some—or perhaps all—and propose a heretofore unexamined explanation.

WHO’S ON FIRST?

The earliest mention of the source of his name is a quotation from Ty himself in a 1956 biography by John McCallum.1

Ty was always addressed as Tyrus in those days. Not until he climbed into the majors did Damon Runyon and Ring Lardner or one of the New York writers shorten it to “Ty.” Ty says he thinks he was the first “Tyrus” in the United States, though folks have named their youngsters after him. (Emphasis added.)

To make such a statement, Ty must have believed that his first name was not only uncommon but also unique, and he must never have met anyone with that name before.

NAMED FOR A GOD?

Ty Cobb’s 1961 autobiography, published just months after his death in July 1961, quotes Ty’s own explanation of the source of his name.2 This book was ghost-written by Al Stump, who would—sadly and with great detrimental effect—produce additional writings after Ty’s death. In numerous magazine articles and books after Cobb’s death, Stump proudly exercised his bent for besotted and perverted fantasies, sensational truth-twisting exaggerations, and out-and-out lies.3 Stump would later assert that the content of the 1961 autobiography was under editorial control of Ty himself, which makes almost everything in the book believable. It reads:

How my father came to pick my name, I am not entirely sure, but the story that it stems from Týr, the Norse god of war, is untrue. Father was an avid reader of ancient history. And the Tyrians of Tyre, an ancient Phoenician seaport, appealed to him. … Tyrus, a Tyrian leader, resisted the Roman invasion, before Alexander slaughtered the population, and from him comes my name.

That a story had previously circulated about Ty being named for the Norse god of war was news to me. I did a thorough search and found no mention of this story in any of the newspapers available on Newspapers.com Having no knowledge of Norse religion or mythology, I did not know if the name carried negative implications, but Ty seemed to think it did, and wanted to quash the story as a result.

I set out to study enough Norse mythology to learn who Týr actually was, and to get a feel whether Ty’s well-educated father, Professor William H. Cobb, might have conceivably considered naming him after this mythical god. Týr is not only the Norse god of war, but also the god of law and honor, and I learned he is deemed extremely intelligent, clever, wise, and cunning—able to create puzzles unsolvable by human minds. Týr’s superhuman powers and abilities allow him to excel in all forms of combat, both armed and unarmed, but he is also a natural pacifist and diplomat who uses his powers to seek peace for his people. All in all, pretty admirable and maybe not such a bad namesake as Ty seemed to believe. In fact, some of Týr’s attributes sound much like attributes that Ty himself would grow up to possess.

Although, Týr is pronounced like “tier” in English, the Latinized name is “Tius,” which is not so far removed from Tyrus. At that point in my investigation, it seemed no more a stretch to reach Tyrus from Týr or Tius, than from the name of an ancient city called Tyre.

WHO NAMES THEIR CHILD AFTER A CITY?

No one I ever knew named their first-born child after a city, ancient or modern. I have no friends or acquaintances named New York, Chicago, Atlanta, or even London, Rome, or Moscow. Certainly not Babylon, Memphis, Nineveh, Thebes, or Carthage. Who would do that?4 Yet that definitely seems to be the consensus among biographers as to the source of the name Tyrus. Not even Ty himself asserted that he was named for the city of Tyre, but rather for a leader of that city by the name of Tyrus. Let’s take a look at some of the assertions of Cobb biographers and their explanations.

In 1975, John McCallum wrote another, more in-depth biography of Ty Cobb. By that time, Ty’s 1961 autobiography had been published, so McCallum updated this 1956 assertion with this statement:

Professor Cobb, an avid reader of ancient history, had always liked Tyrus of Tyre, who had led his people in resistance to Rome before Alexander slaughtered the population of the ancient Phoenician seaport. So he named his son Tyrus Raymond.5

After extensive research I have not been able to find any reference to a person named “Tyrus of Tyre.” So, I believe McCallum errs, as does Ty himself, in stating that Tyrus is the namesake of a person named Tyrus of Tyre. McCallum also errs by stating that Alexander slaughtered the population of Tyre. Actually, the army of Tyre was slaughtered, while the non-combatants were taken as slaves.

In 1984, Charles C. Alexander, a respected historian and university professor with no stated relation to Alexander the Great, wrote a scholarly, well referenced biography also titled Ty Cobb. Echoing Ty’s own statement from 1956, Alexander attributes the name Tyrus to W.H. Cobb’s knowledge of ancient history, expanding the story to include specific mention of Alexander the Great, but avoiding the attribution of Tyrus to a person. Alexander states only that Ty’s father “hit on” the name Tyrus when recalling the city of Tyre.

W.H. Cobb had read about the stubborn resistance of the city of Tyre to the besieging armies of Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C. Thus he hit on Tyrus as a suitable first name for his son. For no particular reason, the infant was given Raymond for a middle name.6

Interestingly, Alexander adds his own twist on the source of Ty’s middle name, Raymond, with a quotation that predates the famous Forrest Gump serial quotation by a full decade: “For no particular reason. …” No reference was given for this assertion.

A prolific history and sports author named Richard Bak from Detroit published another biography of Ty Cobb in 1994 titled Ty Cobb: His Tumultuous Life and Times. Bak went to great lengths in his early chapters to expound on the effect that the Civil War had on the family of Ty Cobb and then described the possible effect that the war had on selection of the name Tyrus—a new wrinkle in the discussion. Without attribution he makes this statement:

It’s even possible that the bitter legacy of Sherman’s march played a part in William Cobb’s naming of Tyrus, because after the war Atlanta often was referred to as “The Tyre of the South,” calling to mind the fate of that other unlucky city.7

Speaking of names, Bak even delves into the namesake of Ty Cobb’s adversary, Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis.8 He pointed out correctly that Landis was named after the Civil War Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, which was fought in Georgia on and around a pair of small ridges known as Big Kennesaw and Little Kennesaw Mountain, near the Atlanta suburb of Marietta. He also pointed out that Landis’ parents misspelled the name of those ridges by dropping an “n” from the usual Anglicization.

However, one must suspect Bak’s knowledge of Civil War history, and hence his unreferenced speculations that Ty’s parents were thinking of General Sherman when naming him. Bak incorrectly states that Sherman’s Union Army won the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, which was actually a resounding Confederate victory. After losing nearly 3,000 men, Sherman withdrew all forces on June 27, 1864.9 This is a major error for any historian, bordering on unforgivable. Bak also asserts that Atlanta was often referred to after the Civil War as “The Tyre of the South.” Atlanta has been called a lot of things in the last century and a half, including “Gate City of the South,” “New York of the South,” “Chicago of the South,” “Convention City of Dixie Land,” “Dogwood City,” and others. But except for a single obscure reference in David Power Cunningham’s 1865 book Sherman’s March through the South, I found no other uses of this moniker.10

The year 1994 also saw the reemergence of Al Stump, a serious nemesis of Ty Cobb. Stump penned his magnum opus, a biography titled Cobb: The Life and Times of the Meanest Man Who Ever Played Baseball.11 The book was adapted into the movie of the same title, directed by Ron Shelton and starring Tommy Lee Jones as Ty. Stump carries on the war-and-warrior naming theme, discarding the Norse-god-Týr theory and expanding on the City-of-Tyre theory:

In naming his first son, the senior Cobb dipped into his interest in war and warriors. Tyrus was not named for Týr, a Norse god of arms-bearing, as would later be claimed by members of the sports press. In 332 B.C., sweeping across Asia Minor, Alexander the Great was halted by defenders of the ancient Phoenician city of Tyre. Through seven months of carnage, the Tyrians kept Alexander’s army at bay. Thence came the newborn’s name. The child’s middle name, which he much disliked, came from a distant relative, a gambler by profession, but friendly with the Professor.

Ever the sensationalist, Stump adds a juicy tidbit, speculating on the source of Ty’s middle name as coming from a distant relative, not necessarily a Cobb, who was also a (gasp!) gambler.12 Throughout his career, Stump peppered his writing with fictional statements to provoke thoughts and speculations about the negative or shady side of his subjects. This is undoubtedly an example.

In 2005 came a second Ty Cobb biography by Richard Bak—Peach: Ty Cobb in His Time and Ours.13 He carries on the story of the city of Tyre and its valiant but unsuccessful defense. Like all the other biographers who propagate this story, no explanation of the leap from Tyre to Tyrus is given.

William, who was widely read, had always admired the story of the ancient Phoenician city of Tyre, which in 332 B.C. had put up a gallant but doomed resistance to the legions of Alexander the Great. Hence the first-born’s unique name.

Charles Leerhsen’s myth-shattering and widely read biography titled Ty Cobb, A Terrible Beauty was published to great acclaim in 2015.14 Leerhsen openly admits that the source of the name Tyrus could have been a name that was invented by his parents, and further speculates that the source of Ty’s middle name Raymond is anybody’s guess.

Tyrus Raymond Cobb was the baby’s full name. Where his parents got “Raymond” is anyone’s guess. “Tyrus,” though it doesn’t sound so strange now (thanks largely to Tyrus Raymond Cobb), may well have been a name of their own invention. (It was only after he started hitting above .300 that people stopped calling him “Cyrus.”) W.H. apparently fashioned it from Tyre, the ancient Phoenician city that in 332 B.C. gallantly held out for seven months before finally falling to Alexander the Great.

Leerhsen does note that Ty’s father “apparently fashioned” the name Tyrus from the name of the ancient Phoenician city of Tyre, acknowledging what most earlier biographers failed to note—that there was no historically significant person in the city of Tyre by the name of Tyrus. No prior biography explains how the name Tyrus was derived from the city name Tyre.

Another Ty Cobb biography was published in 2015, this one by Tim Hornbaker titled War on the Basepaths, The Definitive Biography of Ty Cobb.15 Hornbaker makes only a small mention of the source of the name Tyrus, replaying what Ty said in his 1961 autobiography about the Norse god Týr and the city of Tyre, but he does acknowledge that it is a “rather unusual” name:

Regarding the rather unusual name, Cobb explained that it came from a “Tyrian leader” from Tyre, which today is in modern-day Lebanon. He disavowed a claim that it was from Týr the Norse god of War.

Hornbaker also fails to recognize that there was never a Tyrian leader named Tyrus.

One year later, in 2016, another Ty Cobb biography was published, this one by history professor Steven Elliott Tripp of Grand Valley State University.16 This biography was titled Ty Cobb: Baseball and American Manhood.17 Professor Tripp rehashes the City-of-Tyre theory:

Another indication of William’s attachment to Southern culture concerned the name he chose for his first-born—Tyrus. A student of ancient history, William admired the story of the ancient Phoenician city of Tyre which had resolutely defended itself against a number of invading armies during its storied past. Only the massive army of Alexander the Great was able to conquer it after a long and terrible siege. When Alexander finally broke through, he ordered that the entire Tyrian army be put to death and all its citizens sold into slavery. From a Southerner’s perspective, the similarity between the history of Tyre and what the South had endured in war and reconstruction could not be plainer. William’s choice of Tyrus as a name revealed his allegiance to the cult of the Lost Cause, a growing cultural movement that hoped to keep alive the dream of Confederate nationalism through public rituals and—as in the case of William’s choice of a name for his first-born—private acts. Like the ancient Tyrians, William hoped that his progeny would fight the righteous fight against unwelcome invaders.

Professor Tripp adds “the Southerner’s perspective,” waxing grandiloquent about Professor Cobb’s feelings about the Civil War, alleging—based on no stated facts—an ultimate fidelity to the Lost Cause, linking the naming of Tyrus Cobb to his father’s supposed allegiance to Confederate nationalism. This is no better than Stump’s fantastical inventions.

Professor’s Tripp’s condescending assertion is worse than suspect; it is an ahistorical overreach of massive proportions. Aside from expecting us to believe that he can discern what would be the deeply hidden motivations of a man who had been deceased for more than 12 decades, Tripp completely neglects that Professor Cobb came from a long line of abolitionists and Union sympathizers.

Ty’s grandfather, John Franklin Cobb, was drafted into the 39th North Carolina Infantry Regiment only two months after President Jefferson Davis authorized the Confederacy’s first Conscription Act on April 16, 1862, requiring three years of service from all males aged 18 to 35. He declared to the Confederate officer inducting him in Murphy that he was a Unionist, stating: “I am an American citizen. I am not a rebel,” but he was sworn in anyway.18

He was discharged in August for medical reasons a month before his regiment saw its first combat action.19 Thus he was not, strictly speaking, a Confederate war veteran, and it seems unlikely he would have either held the Lost Cause mentality or propagated it to his son. Tripp also fails to mention that Professor Cobb’s paternal grandfather, William A. Cobb, was a Methodist minister and devout abolitionist who shocked his congregation by preaching against slavery and was run out of the county for his beliefs and his advocacy.20

Strange also that Tripp could believe that Professor Cobb’s naming of his son in 1886 was a hidden act of allegiance to the Lost Cause when less than 20 years later his public acts promoted the exact opposite: as a Georgia State Senator, Cobb advocated successfully for state funding of Negro education. He later worked as editor of the Royston Record, the local newspaper in Ty’s hometown, which was owned and controlled by a well-known abolitionist and Universalist minister.

THE BIBLICAL HISTORY OF THE CITY OF TYRE

All but two of Ty Cobb’s biographers include the City-of-Tyre theory, but none explain how one gets from Tyre to Tyrus. Only Charles Leerhsen states that Cobb’s father “apparently fashioned” it, while Ty himself believed incorrectly that Tyrus was the name of a leader of Tyre. The link between the names Tyre and Tyrus actually comes from the King James Version of the Bible.

The original 1611 edition, with its very old English, was replaced in 1769 by a newer version which became the standard for all English-speaking Christians. This was the Bible in common use by Southern churches around the time of Ty’s birth in 1886, and his father, as an educated man and grandson of a minister, was surely familiar with it. This Bible uses both the names Tyre and Tyrus to refer to the ancient Phoenician city. There is no doubt that the two names refer to the same city, and the prominent use of Tyrus in the books of Ezekiel and Zechariah dispel any assumed need for Ty’s father to “fashion” one name from the other. The names Tyrus and Tyre were used interchangeably throughout.21

Cobb’s biographers consistently attribute the Tyrus name selection to the struggle of that city against Alexander the Great, but there is a rich history of the city both before and after—even into the New Testament time—that lead to many mentions throughout the Bible.

The first mention comes in the Old Testament book of Joshua as one of the cities of the tribe of Asher (~1200 B.C.), a seaport in Syria about midway between Sidon and Accho. The city was partially on an island and partially on the shore. It was a center of great commerce, sending goods to the east by land and to the west by the sea. The island part of Tyre was fortified with a wall recorded to be 150 feet high in places, and it held an exceedingly strong defensive position. Joshua had captured Jericho, but was unable to capture Tyre, and the city later rivaled Jerusalem.

In King David’s reign (~969 B.C.), Israel formed an alliance with Hiram, the king of Tyre. David’s use of stonemasons and carpenters from Tyre, along with cedars from that region, was essential to building his palace. In King Solomon’s reign (957–31 B.C.), the construction of the temple in Jerusalem, about 100 miles away, relied heavily on supplies, laborers, and skilled artisans from Tyre. The seamen of Tyre also aided in navigating the ships of King Solomon.

Israel continued its close ties with Tyre during King Ahab’s reign (~875–53 B.C.). Ahab married the Phoenician princess Jezebel of Sidon, and their union led to the infiltration of pagan worship and idolatry in Israel. Both Tyre and Sidon were notorious for their wickedness and idolatry, which resulted in numerous denouncements by Israel’s prophets, who predicted Tyre’s ultimate destruction.

The book of Ezekiel (~592–65 B.C.) laments for the city of Tyrus, identifying the Prince of Tyrus, who claimed that he was a god sitting proudly in God’s seat. In Ezekiel’s proclamations, God tells the Prince of Tyrus that he is a man and not God. Ezekiel then identifies the Prince of Tyrus as Satan himself. Other curses from God directed at Tyrus that were prophesied by Ezekiel include (among many others): “I am against thee, O Tyrus, and will cause many nations to come up against thee…”; “I shall make thee a desolate city…”; “I bring forth a fire from the midst of thee, it shall devour thee, and I will bring thee to ashes…”22

King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon laid siege to Tyre for 13 years beginning in 586–85 B.C. During this time, the inhabitants transferred most of their valuables to the island. The king seized Tyre’s mainland territories, but was unable to subdue the island fortress militarily and returned to Babylon. Tyre, weakened by the conflict, soon recognized Babylonian authority, which effectively ended the city’s autonomy.

After the restoration of Jerusalem in Nehemiah’s time, the people of Tyre violated the Sabbath rest by selling their goods in the markets of Jerusalem. Following the Babylonian period, Tyre remained in subjection to Persia from 538 to 332 B.C. In 332 B.C., Alexander the Great besieged and conquered the port city after a seven-month siege. He conquered the island part of the city by building a 200-foot-wide land bridge from the shore which still exists today. Afterwards, the Ptolemies, the Seleucids, the Romans, and the Muslim Arabs all had their turn at rule.

In the New Testament, Jesus mentions Tyre as an example of an unrepentant city (~A.D. 30). Jesus also ministered in the district of Tyre and nearby Sidon, healing the demon-possessed daughter of a Canaanite woman there.

The persecution that arose after Saint Stephen’s martyrdom (A.D. 36) caused the Christians in Jerusalem to disperse. As a result, a Christian church was established in Tyre which is said to contain a stone that Jesus sat upon when he visited there. Saint Paul later spent a week there with the disciples on the return voyage of his third missionary journey (~A.D. 58).

From the time of Christ up to the Crusades, Tyrus was a flourishing city of commerce, renowned for the great wealth it derived from dyes of Tyrian purple, extracted from shellfish on its coast.

In 1124, Tyre was captured by the first Crusaders, and later was successfully defended by them in the four-month Siege of Tyre by Saladin in 1187–88. It finally fell to the armies of the Mamluk Sultan Khalil in 1291, and the city was completely destroyed by the Saracens, thereby fulfilling Ezekiel’s prophecy: “They will destroy the walls of Tyre and pull down her towers…” The island part of Tyre remained a desolate ruin for centuries.

Although not biblical history per se, Shakespeare would later (1609) immortalize the city of Tyre in his play Pericles, Prince of Tyre.23 In this story, the Seleucid King of Syria, Antiochus the Great (222–187 B.C.), had a beautiful daughter who had many suitors. He discouraged all suitors by requiring each to solve a riddle in order to pursue her. If a suitor gave the wrong answer to Antiochus’ riddle, he was killed. When Pericles, Prince of Tyre, did solve the riddle, Antiochus attempted to kill him as well. But Pericles was repulsed by his correct answer to the riddle, which was that Antiochus and his daughter were in an incestuous relationship. Fearing death, Pericles fled back to Tyre with Antiochus in pursuit. The play covers the later trials and tribulations of Pericles and his family through many episodes of shipwrecks and tragedy, until Pericles is finally reunited with his own daughter, Marina.

Of course, there is a long tradition of giving children names found in the Bible, perhaps more notably thought of as a Southern practice now, as names like Ezekiel, Josiah, and Zebediah remain more prevalent in the Southeast than elsewhere in the US, but Biblical naming was certainly a popular practice in both North and South at the time of Ty’s birth. Given the repeated appearance of the name Tyrus in the Bible, one might expect to find other Tyruses in the historical record. But how does this fit with Ty’s own belief that his name was unique or that he might have been the first?

WHAT’S IN THE DATABASES?

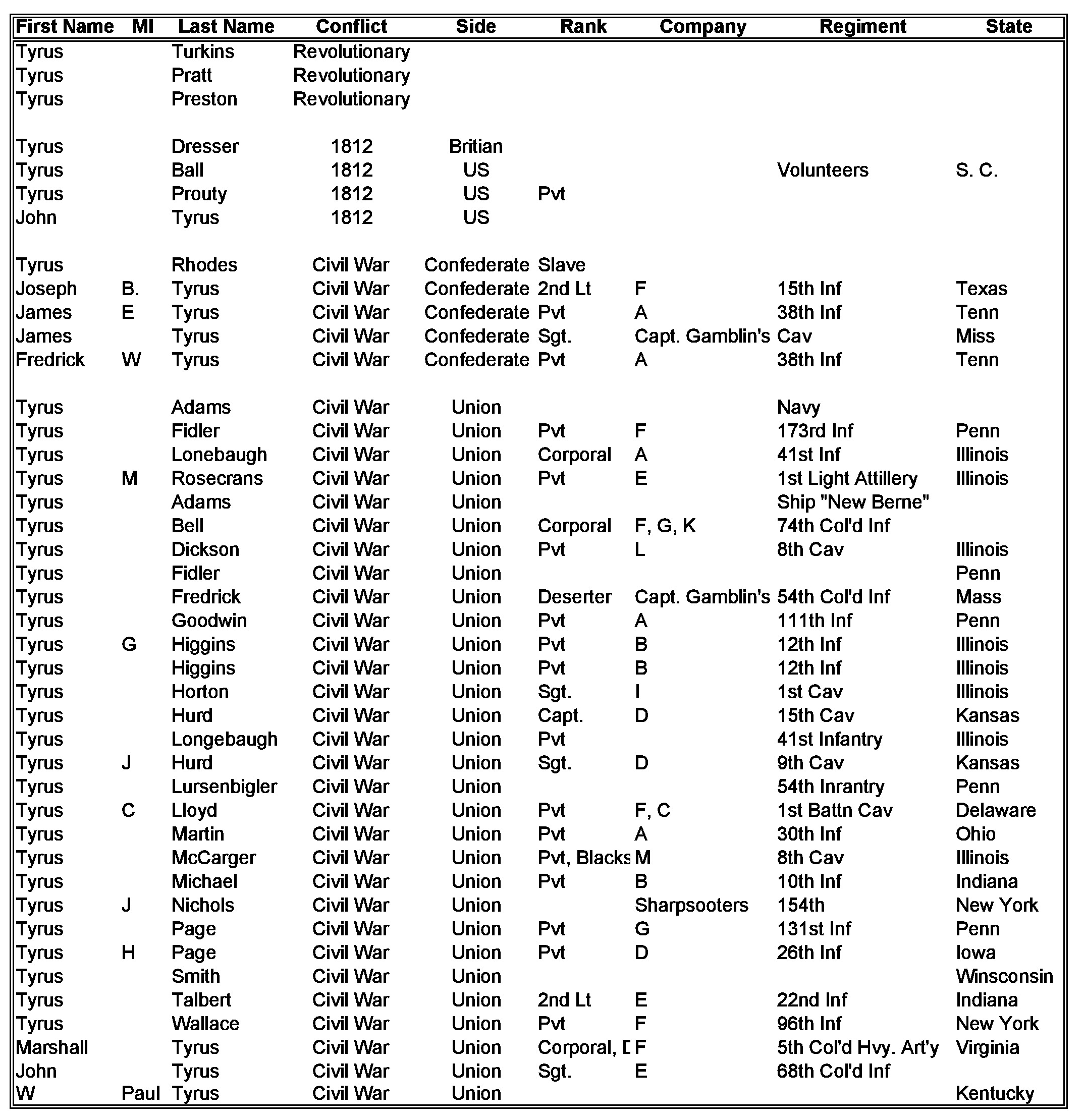

While working on a book about the Civil War and looking for roster information about the 8th Regiment of Georgia Volunteer Infantry, I accessed a massive online database of military service records of US soldiers from the Revolutionary War onward.24 On a whim, I did a search on the name Tyrus over the entire database. I was surprised by what I found. My search shows that the name Tyrus was not nearly so unusual as previously supposed. There were actually many soldiers throughout history who bore that name.

Three soldiers fought in the Revolutionary War with the first name Tyrus, and three more in the War of 1812. One soldier in the War of 1812 had the last name Tyrus, and one soldier in the Mexican American War of 1846 had it as his first.

In the Civil War, a total of 28 soldiers had the first name Tyrus, 27 Union and one Confederate. Clearly the popularity of that name was much greater in the North than the South, perhaps explaining why Ty knew no other person who shared his own first name. In addition, there were seven soldiers whose last name was Tyrus, four Confederates and three Union (Exhibit 1). Continuing the search, I found 70 soldiers who served in World War I with the first name Tyrus, 22 soldiers with the last name Tyrus, and 47 soldiers with the middle name Tyrus. These soldiers were contemporaries of Ty, and thus he could not have been their namesake. Clearly, although the name Tyrus was not a common name, it was not an unheard-of name either (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 1. Soldiers with the Name Tyrus, 1775-1865

Exhibit 2. World War I Soldiers with the Name Tyrus

Last names of 70 soldiers with first name Tyrus

Bailey, Bateman, Benton, Berry, Bingham, Caswell, Clide, Cobb (2), Collins, Conklin, Cooke, English, France, Freeman, Frost, Garrett, Gray, Habegger, Harris, Heindel, Heinmann, Hewet, Hill, Hilton, Holmes, Holt, Howard, Hunker, Hunter, Jefferies, Johnson, Joyce, Kehmier, King, Lane, Larson, Lemon, Lengle, Lesley, Lindsay, McCargar, McEwan, Meyer, Meyers, Middleton, Nuss, Peck, Peters, Phillips(2), Pittman, Price, Price, Ruston, Settle, Shaffer, Sims, Strohl, Syng, Thompson, Thorpe, Ulysses, Walters, Whitehorn, Youngblood, Youse

First names of 22 soldiers with last name Tyrus

Archie, Arthur, Cleveland, Clyde, Forrester, Gail, Henry, James, Joe, John (2), L. B., Lindsay, Marion, Robert (2), Rogers, Tidor, Timpko, Tom, Ulysses, Willie

Last names of 47 soldiers with middle name Tyrus

Barnard, Blacklock, Broadhead, Clark, Cash, Cobb (2), Epler, Flanders, Harper, Heimann, Hollon, Hovan, Hower, Jacobsen, Jones, Leigh, Lemaire, Lindsay, Long, Mainer, Martin, McChargue, Meimann, Money, Muggridge, O.Malley, Page, Pempin, Poska, Ray, Rhoad, Savage, Sharp, Shoener, Smith, Sooy, Sunderland, Tidwell, Vaughan, White, Wilfong, Wilfong, Willington, Wimberly, Wolf, Wyckoff

The database yielded more of note: two World War I soldiers with the first name Tyrus and last name Cobb (Tyrus Raymond Cobb of Georgia and Tyrus Anton Cobb of Indiana) plus two with the middle name Tyrus and last name Cobb (Harry Tyrus Cobb and John Tyrus Cobb, their resident states not recorded). Among the 1,216 draft-registered soldiers surnamed Cobb, a total of four had the first or middle name Tyrus.

In World War II, I found even more soldiers named Tyrus. Of course, many of these soldiers were named after Tyrus Raymond Cobb by parents who must have been baseball fans. There were over 3,000 service records of soldiers with either first or last name Tyrus, and 329 with the name Tyrus Raymond or Raymond Tyrus. Nineteen actually had the name Tyrus Raymond Cobb, without a doubt a tribute to Ty Cobb, and of these, two had this three-name tribute to Ty preceding a different surname. In the Korean War I found only 122 soldiers with the first or last name Tyrus.

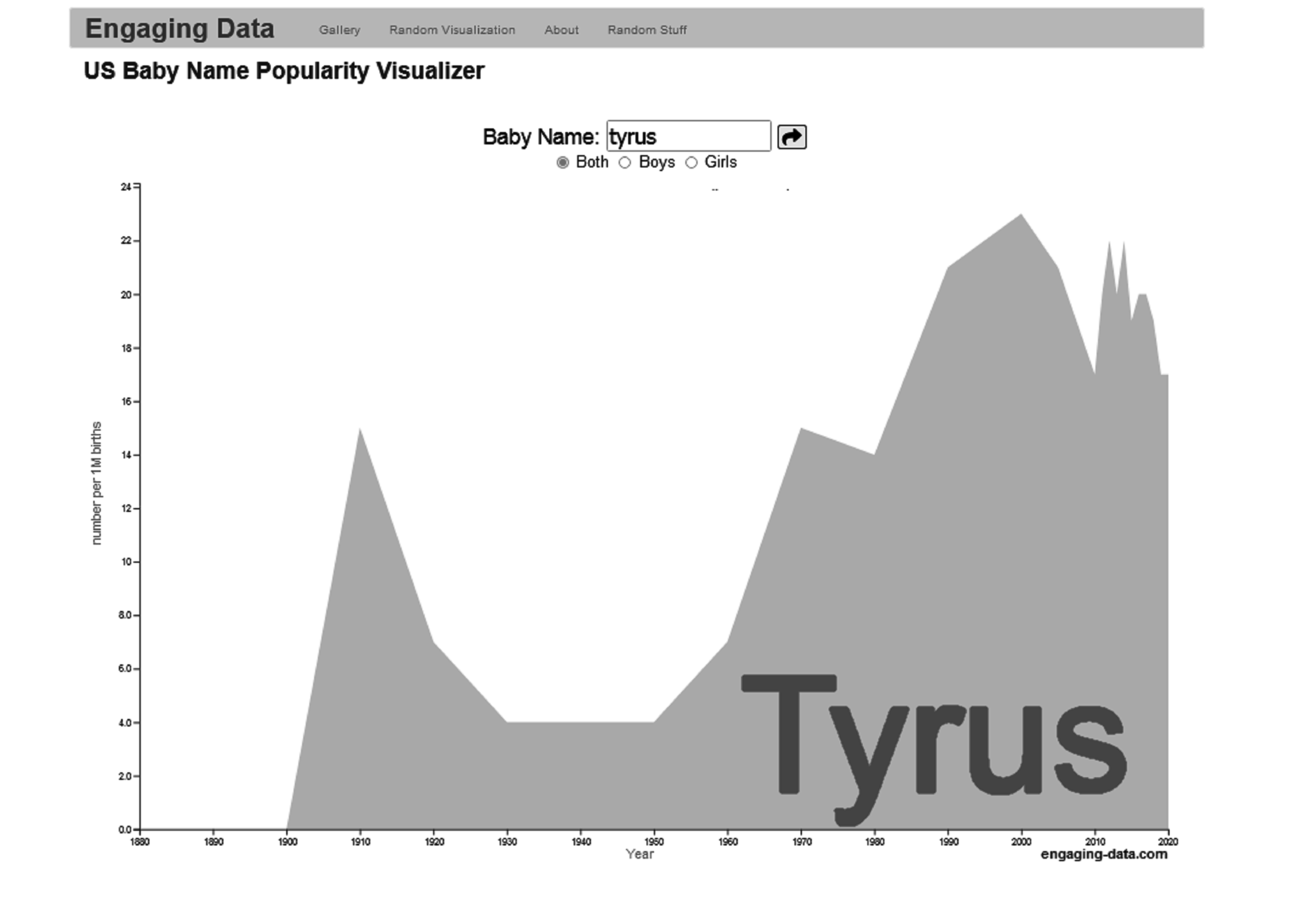

Other sources of names I found include the Social Security Death Index (SSDI), the Social Security Birth Name database, and several other online databases. SSDI shows first, middle, and last names with birth year and death dates. Seven people with the first name Tyrus were born before Ty Cobb’s birth in 1886. (SSDI also shows one individual named Tyrus Raymond Cooke born in Missouri in 1889.) As expected, the number of people with the first name Tyrus increased dramatically beginning in 1909, matching the rise of Ty Cobb’s baseball fame. In all, there are 957 records for persons with the first name Tyrus, 224 with the middle name Tyrus, and 122 with the last name Tyrus, although there are some duplicate records within this data.

I was unable to gain direct access to the Social Security Administration Birth Name database, but did find a website which provided a visualization of selected names from that data.25 Exhibit 3 shows a plot of babies named Tyrus from 1900 through 2020, although the website cautions that data before about 1935 are not necessarily accurate. As expected, the plot shows rapid increase beginning after 1905 when Ty Cobb began to gain fame in baseball. Interestingly, it shows another significant increase around 1961, the year of Ty’s death. And finally, it shows a marked decrease in the late 1990s which might be attributed to the negative myths that were fabricated and popularized by Al Stump in his 1994 book and in the subsequent movie about Ty Cobb.26

Exhibit 3. Babies Named Tyrus, 1905﹣2020

ANALYSIS AND CONCLUSION

Firm conclusions about century-old individual actions and feelings are simply not possible. But this study has shown that several widely believed facts regarding the name Tyrus are either not true, or are not likely, and lead to one new piece of analysis. Here is a summary of what I have gleaned from this study:

Ty was quoted by John McCallum in 1956 as purportedly saying that he believed he was the first person in the US to be named Tyrus.27 The data reviewed here show he was definitely not the first in the country with that name.

Ty’s own 1961 autobiography stated he was named after a leader of the city of Tyre by the name of Tyrus. This cannot be correct, as there was no historical person named Tyrus who led the city of Tyre in its defense against Alexander the Great, and Ty’s statement includes several other historical mistakes including Alexander the Great leading a “Roman invasion” (Alexander was Greek).

Ty did offer the caveat, “I am not exactly sure,” when describing how his father picked his name, yet he seemed to be quite emphatic he was not named for the Norse god Týr. Given that Týr was actually a pretty good guy, it might not be completely out of the question that Ty’s father could have chosen Tyrus based on that.

Cobb’s biographers all parroted the City-of-Tyre theory in some form, many citing the city’s resistance to Alexander the Great as the supposed inspiration.28 Two tried to create a presumed link between the name Tyrus and the Southern Confederacy, neither of them credible. None recognized that “Tyrus” was actually the name of the city as written in several books of the King James Version of the Bible.

Presumably, following the convention of using biblical names, Professor Cobb might have taken it from the KJV Book of Ezekiel, where the name Tyrus is used exclusively and appears a dozen times in chapters 26–28 alone. But given the centuries-long condemnation of the wickedness of the city of Tyre described in the Bible, why would Professor and Mrs. Cobb would even consider naming their firstborn after Tyre at all? Not to mention that cities don’t seem to be typical sources of baby-naming at all?

The final conclusion of this study is that we don’t know why Professor Cobb and his wife named their first son Tyrus, and even Ty himself, as he clearly stated, did not know. However, it seemed to me a striking coincidence that in World War 1 there were two soldiers with first name Tyrus and last name Cobb (one of which was Tyrus Raymond) and also two soldiers with middle name Tyrus and last name Cobb. To examine this further, I asked the SABR Statistical Analysis Committee for assistance in analyzing these WWI name probabilities.

Here is how they posed the statistical problem: Assume a random distribution of the names of the 4.6 million soldiers which we know were in service in World War I. Of these 4.6 million soldiers, we also know there were a total of 117 soldiers with the first or middle name Tyrus—70 with first name Tyrus and 47 with middle name Tyrus.

It happens that 1,261 of the 4.6 million soldiers were surnamed Cobb. The probability that any specific one of the soldiers named Tyrus would be surnamed Cobb is easily calculated as 1261/4.6 million, or 1 in 3648. But, of the 117 soldiers with first or middle name Tyrus, there were actually 4 surnamed Cobb. What then is the probability that at least 4 of the 117 Tyruses in WWI were surnamed Cobb? That answer, assuming as usual a binomial distribution, turns out to be 1 in 26 million.29

The extremely low probability that 4 of the 117 Tyruses in WWI would be surnamed Cobb means that it is not merely a coincidence. I postulate that these Tyrus Cobbs were actually related to each other in some way. If this is true, then the source of the name Tyrus for the baseball player was from within the Cobb family and actually came from an ancestor or relative named Tyrus Cobb, not an ancient city cursed for centuries by the Judeo-Christian God and not the benevolent Norse god of war, law, and honor.

DR. WILLIAM “RON” COBB, PhD, is a retired Engineer and Management Consultant who spends his time researching and writing history—mostly baseball and the Civil War. He has nine books to his credit. Ron served on the Board of Advisors of the Ty Cobb Museum from 2004–14, rejoined in 2018, and continues to serve in this position. Ron authored the breakthrough SABR National Pastime article in 2010 that first exposed Al Stump’s forgeries and fake Ty Cobb memorabilia enterprise.

1 John McCallum, The Tiger Wore Spikes, An Informal Biography of Ty Cobb (New York: A.S. Barnes and Co., 1956), 18.

2 Ty Cobb with Al Stump, My Life in Baseball, The True Record (New York: Doubleday, 1961), 34.

3 William R. Cobb, “The Georgia Peach: Stumped by the Storyteller,” The National Pastime: Baseball in the Peach State (Society for American Baseball Research, 2010).

4 A recent Internet search for “Famous people named after cities” has proven me wrong, at least for modern glitterati and their children— obviously a present-day phenomenon. Here are just a few from those search results, most of whom are completely unknown to me: Paris Hilton, Paris Brosnan, Orlando Bloom, Bristol Palin, Brooklyn Decker, Brooklyn Beckham, Cheyenne Jackson, London Hudson, Chicago West, Kingston Rossdale, Bronx Wentz, Milan Mebarak, Savannah Guthrie, Santiago Cabrera … The US Baby Name Popularity Visualizer (https://engagingdata.com/baby-name-visualizer) which draws data from the Social Security Administration’s baby Names website (https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/babynames/background.html) shows Paris to have been a popular choice pre-dating the 1880 start of the database, perhaps more due to the name of the Trojan War hero Paris than the French city, although I will note that Memphis suddenly came into use as a baby name in 1990 and has had a meteoric rise since.

5 John McCallum, Ty Cobb (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1975).

6 Charles Alexander, Ty Cobb (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984), 9.

7 Richard Bak, Ty Cobb, His Tumultuous Life and Times (Dallas: Taylor Publishing Company, 1994), 5.

8 “More Trouble in Mudville,” Sports Illustrated, May 28, 1973, https://vault.si.com/vault/1973/05/28/more-trouble-in-mudville, accessed August 31, 2023.

9 The Confederates lost fewer than 1,000.

10 David Power Cunningham, Sherman’s March Through the South (Bedford: Applewood Books, 1898), 238. Originally published in 1865.

11 Al Stump, Cobb, The Life and Times of the Meanest Man Who Ever Played Baseball (Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1994), 32.

12 The 1880 Census does list four individuals named Raymond Cobb, a six-year-old in Missouri, a one-year-old in Florida, a 30-year-old in Pennsylvania, and a two-year-old in New York. None of these were listed in the Census with the occupation of gambler.

13 Richard Bak, Peach: Ty Cobb in His Time and Ours (Ann Arbor: Ann Arbor Media Group, 2005), 14.

14 Charles Leerhsen, Ty Cobb, A Terrible Beauty (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015), 24.

15 Tim Hornbaker, War on the Basepaths, The Definitive Biography of Ty Cobb (New York: Sports Publishing, 2015), 2.

16 Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article included two errors regarding Steven Elliott Tripp’s title and background. He is a professor in the History Department at Grand Valley State University, not the Sociology Department. He did not host a podcast series.

17 Steven Elliott Tripp, Ty Cobb, Baseball, and American Manhood (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016), 8.

18 Leonora Cobb Spencer, Cobb Creek: An Account of the Cobb Family and Pioneer Days, with a Biographical Sketch of Tyrus Raymond Cobb (Murphy: Southwest North Carolina Genealogical Society, 1982), 29. Leonora was Ty’s Aunt Nora, sister to his father and the daughter of John Franklin Cobb. Based on dates referenced in the text, the text of Cobb Creekwas written around 1920 and survived within the family and community until it was bound and printed in 1982 by the Southwest North Carolina Genealogical Society. Nora’s quotes about John Franklin Cobb’s Confederate service were likely from her recollections of stories she was told as a youngster.

19 Leonora Cobb Spencer, Cobb Creek, 29.

20 Leerhsen, 29.

21 As part of my investigation, I checked out an earlier Latin Bible to see what term it used for Tyre and Tyrus. Much to my surprise, there were even more variations of the name. A total of five variations were present in the 26th chapter of Ezekiel alone: Tyrus, Tyre, Tyro, Tyrum, and Tyri. I consulted a Latin expert who explained that the Latin language has cases, meaning that nouns take different forms depending on their role in a sentence. English also has cases, but to a much lesser degree, i.e., the book and the book’s cover. Latin has six cases, and five of them appear in this chapter of Ezekiel. They include nominative case (Tyrus); vocative case, used when talking directly to someone (Tyre); genitive case, the same as the English possessive (Tyri); accusative case, showing the object of the sentence (Tyrum); and dative case, showing the indirect object (Tyro). I don’t claim to understand all this well, but describe it here to further illustrate that the forms Tyrus, Tyre, and others in Latin all refer to the same thing: an ancient Phoenician coastal city, not to a person.

22 Ezekiel, Chapter 26, KJV.

23 William Shakespeare, Pericles, Prince of Tyre (London: Henry Goffon, Publisher, 1609).

24 Fold3, a service of Ancestry.com, at https://go.fold3.com, accessed July 2022. Fold3 includes the military service records of the US, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

25 US Baby Name Popularity Visualizer, Engaging Data, https://engaging-data.com/baby-name-visualizer/, July 2022

26 I examined several other online databases, such as Ancestry.com, but found that they provided so many conflicting and duplicate name listings that they were not useful to my study.

27 It cannot be said with certainty that Ty ever actually made this statement, since McCallum’s 1956 biography was “unauthorized.” It is doubtful that Ty would have given this quotation to McCallum for use in an unauthorized biography, though he might have made the statement in an earlier conversation when McCallum was a sportswriter for several northwestern newspapers in the early 1950s.

28 One wonders why Professor Cobb would have been so impressed by the unsuccessful defense of the city of Tyre against Alexander’s seven-month siege, which resulted in its complete destruction. Does it not seem likely that Professor Cobb might be more impressed by the city of Tyre’s successful defense in a 13-year siege by King Nebuchadnezzar II, which failed to capture the island fortress of Tyre, and after which the disheartened Babylonian king packed up and went home?

29 Private Communication from Phil Birnbaum, Chairman of the SABR Statistical Analysis Committee, email dated September 1, 2022.