Umpire Schools: Training Grounds for the Guardians of the Game

This article was written by Bill Pruden

This article was published in The SABR Book of Umpires and Umpiring (2017)

In September 2005 the confirmation hearings of John Roberts as the nominee for chief justice of the United States included an unexpected but telling nod to the national pastime when Roberts observed, “Judges and justices are servants of the law, not the other way around. Judges are like umpires. Umpires don’t make the rules; they apply them.”1 He went on to say, “The role of an umpire and a judge is critical. They make sure everybody plays by the rules. But it is a limited role. Nobody ever went to a ball game to see the umpire.”2

While the analogy itself may be open to debate, Roberts’ comments linked the two professions in an interesting way and, in fact, further investigation reveals that another similarity between the two roles is the way the formal preparation for them has evolved from the more practical, sometimes apprentice-like training that characterized the experience both of early American lawyers and umpires, to the more formalized, structured educational experience that is central to the training of their modern counterparts.

Preschool Days

The road that marked the transition of umpiring schools from curiosities to their establishment as the official gateway to umpiring in the minor and major leagues has been a long and sometimes meandering one. The end product is a result of individual initiative coupled with changing attitudes about the all-important role of the umpire in the game of baseball. Too, the development of the umpiring school as a required part of the career path that leads to the major leagues is an important part of the development and professionalization of baseball, one that brought a structure and consistency to a process previously characterized more often than not by human interaction and unplanned happenstance, where becoming a major-league umpire was more likely a happy accident than the final rung on a progressive career ladder. Indeed, the schools represented a significant change from a system that really was not systematic, with the path to becoming a major-league umpire more often than not being an uncharted and unscripted one. Sometimes it was a case of knowing someone who knew the right person who could open the appropriate door, while at other times it was all about being in the right place at the right time as an amateur or lower-level umpire was stumbled upon by a baseball-wise scout or executive who, looking for a potential player, could not help but notice the skill of the attendant umpire. He would then pass the word to the appropriate league officials and the rest would be history.3

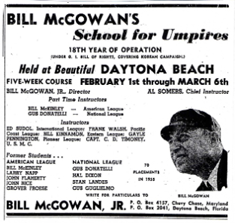

1958 Sporting News ad for Bill McGowan’s School for Umpires.

The Development of the Umpire Schools

This began to change, however incrementally, in 1935 when the first umpire school was opened by George Barr, a National League umpire.4 Ironically, what has become a required part of the path to becoming a major-league umpire began simply as an entrepreneurial enterprise at a time when a professional umpire underwent an apprenticeship-like experience, and not one that included a formalized educational component. Barr’s establishment of the first umpiring school changed all that and when his effort was complemented in the winter of 1938-39 by the opening of another school by Bill McGowan, an American League umpire, the direction of umpire training, not to mention the road to the major leagues, began to change.5 Mandatory attendance at an umpire school was still many years off, and in fact, when Bill McKinley, who attended both schools, joined the ranks of major-league umpires in 1946, it was the first time an umpire-school trainee had reached the major leagues. However, within a decade, school-trained umpires were common, and by the end of the 1960s it had become all but impossible to be hired as a professional umpire without formal school training. Indeed, Jim Evans, whose rookie major-league umpiring season was 1972, was the last major-league umpire to be hired without umpire-school training, and by the 1990s attendance at one of the approved schools had been added to the list of basic requirements for anyone aspiring to be a major- or minor-league umpire.6

Interestingly, unlike the other schools that would follow Barr and which operated out of Florida, from 1935 to 1940 the pioneering George Barr Umpire School was located in Hot Springs, Arkansas, where it operated in conjunction with the Ray Doan Baseball School.7 However, in 1941 Barr moved his school to Florida, initially Orlando, where it would continue, except for a brief interlude in Tulsa, Oklahoma.8 Meanwhile, McGowan never ventured away from Florida and in fact took full advantage of the weather and other attractions that would lead Florida’s tourism industry to explode in the aftermath of World War II. Indeed, such realities were particularly important in the early going, for while their dedication to the profession was clearly central to Barr and McGowan’s early efforts, their schools were also entrepreneurial business ventures looking for customers and their early marketing efforts did not ignore those factors beyond the allure of the baseball diamond that might serve to enhance a prospective student’s experience. Veteran major-league umpire Ed Sudol, who attended McGowan’s school in the early 1950s after a lengthy minor-league playing career, recalled leafing through The Sporting News in the winter, at a point when his future in baseball, especially the likelihood of finally reaching the majors, was looking increasingly dim, and saw an ad that caught his eye. Featuring a picture of a bikini-clad beauty basking in the sun next to an oceanside palm tree, the advertisement touted Bill McGowan’s Umpire School, declaring, “Enjoy the beautiful girls and the climate under a six week course of tutoring to become a professional umpire.” While the motivations of the future umpire may not have been purely professional, Sudol nevertheless responded to the ad exactly as McGowan would have wanted, mailing a letter that night, that said simply, “Dear Bill: Count me in.”9 On such experiences were careers like Sudol’s and the success of the schools based.

The Barr and McGowan schools continued operations during World War II and were thriving as baseball emerged from the global conflict more popular than ever. While Barr continued to run his camp until he retired in the mid-1960s, McGowan died in December 1954, and for two years veteran Pacific Coast League umpire Al Somers, who had long served as the chief instructor under McGowan, oversaw the operations of the school while McGowan’s son handled the business side. After some often acrimonious negotiations between McGowan’s widow and Somers, the school was ultimately sold to him, and beginning in 1957 it operated as the Al Somers Umpire School.10

Umpires in training at the Al Somers School. Undated photograph.

After a successful two decades running what had become the preeminent umpire school in the nation, in 1977 Al Somers sold the school to veteran National League umpire Harry Wendelstedt. It was a fitting succession, for the Somers School had been central to the development of Wendelstedt’s career, one that had been launched back in 1962, when Wendestedt, contemplating re-enlisting in the Marines, instead enrolled in Somers’ school. That experience proved to be the launching pad for one of the most distinguished careers in umpiring, one which saw Wendelstedt, after only four years in the minors, reach the majors, where he would umpire for 33 years before retiring in 1998. Wendelstedt never forgot his professional roots, and after reaching the majors he returned to the Somers School annually to serve as an instructor. Wendelstedt died in 2012, but the school continued to thrive under the leadership of his son, Hunter, himself a major-league umpire.11

Drill in progress, Wendelstedt School, January 2017.

Meanwhile, looking for a way both to standardize the quality of work as well as oversee the development of umpires, in 1965 MLB initiated the Umpire Development Program (UDP), which for the most part was made up of a single supervisor whose job it was to travel around the country assessing the quality and progress of minor-league umpires. Using the UDP, Major League Baseball funded the oversight and development by the minor leagues of minor-league umpires until 1997. At that time it decided that what had become a $5 million annual cost was not worth the return, given that new umpires were hired at the rate of one every other year.12

In 1969 Organized Baseball made an effort to start its own instructional program, which it called an “umpire specialization course” for young umpires deemed to have major-league potential. But after five years it abandoned the scheme, selling it to umpire Bill Kinnamon, who operated it for about a decade before he sold it to Joe Brinkman.13 By the early 1970s, the Somers Umpiring School was the established leader of the field, with the second spot filled by a succession of others, beginning with the long-established Barr School, then by the Umpire Development Program, which morphed into the Umpire Development School, which in turn became the Bill Kinnamon Umpire School in 1971.

In 1982 major-league umpire Joe Brinkman bought the school from Kinnamon and gave it his own name. Like the transition from Somers to Wendelstedt, the move from Kinnamon to Brinkman was both a smooth and a fitting transition. Brinkman’s major-league umpiring career began in September of 1972, following a short stint in the Somers School in 1967 as well as some time with the Umpire Development Program, with that training leading to an initial job in the Class-A Midwest League in 1968. As a young umpire living in St. Petersburg during the winters of the early 1970s, he checked in at the Umpire Development School, and in 1973, just as his major-league umpiring career was starting, he began serving as an instructor at the Bill Kinnamon Umpire School. In 1985 the Joe Brinkman Umpire School relocated to Cocoa, Florida, where Brinkman continued as the owner and an instructor until 1998. That year he sold it to Jim Evans, who folded it into his own operation.14 Evans had, in fact, started his own school in 1990 after receiving permission from MLB. Seeking to provide a geographical alternative to the Florida-based Wendelstedt and Brinkman operations, he chose to run the school in Arizona, an effort that mirrored the shift of some major-league teams’ spring-training operations from Florida to the Arizona desert. Then in 1993 he moved it to Kissimmee, Florida.15

Beginning in the late 1990s, aspiring major-league umpires had to attend one of the two approved schools — Evans and Wendelstedt — who in turn annually recommended their top graduates to the Professional Baseball Umpiring Corporation (PBUC) which, with responsibility for the administration of minor-league umpires, would place them in the appropriate entry-level positions.16

As baseball moved into the twenty-first century, both schools were thriving when, in 2012, a new entry, The Umpire School, sponsored and underwritten by Minor League Baseball, opened its doors. The school held its sessions at the Vero Beach Athletic Complex, a storied baseball venue, familiarly known as Dodgertown, which had been the home of the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers’ spring-training efforts from 1948 until 2008.17 The Umpire School, which beginning in March 2015 began to operate under the name Minor League Baseball Umpire Training Academy, quickly became a well-regarded source of young umpires.18 Its competitive position was strengthened when Minor League Baseball announced it was cutting its ties to the Jim Evans Academy in February 2012, in the aftermath of a racially charged incident at a staff party at the conclusion of a school session. While Evans himself made no excuses and condemned the actions of his employees, he also expressed his belief that the severance of ties between his school and Minor League Baseball, a decision that meant that graduates of his school would no longer be sent to the PBUC, was an excessive punishment. He also raised questions about whether there was not a conflict of interest given that Minor League Baseball was running its own Umpire School as well as certifying the others, all while serving as the placement agency for the top graduates each year.19

Not surprisingly, Evans’s objections fell on deaf ears. However, despite his lack of a formal connection to Minor and Major League Baseball, as of 2017 he continued his operation. The school’s marketing made much of its long history and the accomplishments of alumni who have gone on to work in the major leagues, while also touting the high-quality preparation for professional umpiring positions that the school offered. However, it was also very careful to include a wide range of options under the label of professional umpiring, while scrupulously avoiding any direct connection to the current process through which the top graduates of the certified schools were being placed in minor-league jobs.20 But while graduates of the Evans School can subsequently attend either of the certified schools as a next step on the path to the majors, such an option represents an added, expensive barrier and as baseball approached the 2016 season, the only approved options were the Wendelstedt School and the Minor League Umpire Training Academy.

Instruction in progress at the Wendelstedt School, January 2017.

Life in School

For all their history and the twists and turns that have led ultimately to the pair of schools that as of 2017 served as the gateway to a career umpiring in the minor and major leagues, it is the experience and the training that the aspiring umpires receive that is at the heart of the school experience, while making it a required part of any major-league umpire’s professional journey. At the same time, the rules of baseball, as well as the very nature of the job, limit the individuality of any umpire’s performances. In fact, so standard can the curriculum appear that Bill McKinley, who had attended both the Barr and McGowan schools on the way to becoming the first school-trained major-league umpire, once said that there was little real difference between the schools beyond the fact that Barr taught his students to use the inside chest protector (as used in the National League) while the American League’s outside protector was the choice at the McGowan School.21

Regardless of the specific program, the curriculum and the practical instruction offered aspiring umpires by the schools were consistently rigorous and intense from the start. Each was pursuing the same goal. In the words of one veteran instructor, they wanted to make each student “think like an umpire, not like a player or a fan,” adding that “Old habits must be broken.”22 From the start, the schools were intent on training and preparing prospective umpires for the harsh realities of the profession. Instruction was followed by tests, more instruction, and more tests. Meanwhile, out on the field every gesture was subject to being critiqued and assessed. It could leave even the best student fatigued and confused. As one instructor noted, “[We] spend the first 3½ weeks building people up, and we spend the last week and a half breaking them down to see if they can handle the pressure.”23 All of this not only served to prepare future umpires for the challenges of their chosen profession, but like schools that train other professionals, it also helped weed out those not fully equipped to handle the demanding, pressure-filled role.

At the same time, the experience has been at least a little different at each school, with those often subtle differences reflecting the distinctive approach, philosophy, and personality of their founders and directors. Not surprisingly, given his experience and his reputation, McGowan’s school featured a textbook that he wrote. With a mixture of “Do’s” and “Don’ts,” the book offered directives and guidance on everything from equipment and personal appearance to proper hand signals and positioning. In addition to an extensive text, it also included position sketches and a number of practice tests. Instructions explained in the textbook, covered in the classroom, and then reinforced in the practical exercises on the field included everything from how to sweep off home plate to the proper way to indicate fair and foul balls as well as the appropriate gestures to go with calling balls and strikes.24 Drawing upon a wealth of personal, professional experience, McGowan tried to anticipate every question and situation. Meanwhile, Bill McKinnamon saw his mission as focusing on technique and mechanics. He noted that “[You] can’t teach judgment,” adding, “If a man has poor judgment he is not going to make it as an umpire anyway.” He averred that “Good mechanics — position — is the only thing that will keep you out of trouble. Consequently, we try to give as much on-field instruction as possible — walking through play situations, footwork, timing, working actual games.”25 Al Somers shared this view, asserting, “You cannot teach someone judgment, just technique.”26 He added that he believed former players made “lousy” umpires because “[T]hey’re used to applause, not boos,” no small thing when training for the profession includes “creat[ing] rhubarbs just to see how [the] students will react.”27 Alternatively, from its beginnings in 1990, Jim Evans’s school always prided itself on personalized instruction, promising a teacher/student ratio that would never exceed seven to one.28 At the same time, Evans, seen as a rulebook expert, saw the rules as the foundation of the umpire’s authority on the field. Consequently, students at his school historically spent more time on classroom coverage and discussion of rules.29 The Wendelstedt School takes a different approach, believing that while the rules are obviously important, an umpire’s strength and authority comes from game experience. As a result, students at the Wendelstedt School spend considerably more time in action, umpiring games between local high-school and college teams, opportunities that allow the students to get real experience and, especially importantly, “live pitching.”30 In contrast, Evans maintained that games actually limit what students see. Rather, believing that in reality most games are “parades of the run of the mill,” the Evans school devoted large amounts of time to simulations, where the instructors created situations that the students must address.31

From the beginning with Barr’s school, the basic session was five to six weeks long, always taking place in January and February. This remained the basic model, until the Minor League-sponsored Umpire School compressed its program into four weeks.32 Meanwhile, regardless of the school, the daily program was pretty much the same with a full day beginning with a morning session in the classroom where the aspiring arbiters were drilled on the rules, rules interpretations, and proper positioning. They viewed and studied films illustrating the various situations they might encounter and then they were tested on all of it. The afternoon sessions featured hands-on instruction and workouts on the field. These workouts often included simulations that almost always use the two-man system that is standard in the minor leagues. These lessons included controlled games, simulated contests in which countless situations are presented and assessed.33 In addition, the students also got game experience by working local high-school and college contests.34 And while evenings were usually a time to relax, they also offered study time for the many tests the students took. There also were periodic evening Q&A sessions with major- and minor-league umpires. Meanwhile, occasional organized or informal social events helped begin to develop the camaraderie and sense of team that is no less important to being a successful umpire.35

More than Rules

Yet for all the formal instruction, all the schools’ leaders have long recognized that there was more to being a successful umpire than knowing the rules and soaking up what was taught in the classroom and on the field. Rather, their many years of experience left Barr, McGowan, and company well aware that developing a certain type of personality and character was no less important to becoming a successful umpire than a mastery of the mechanics. Indeed, that was why Barr was known to levy a 10-cent fine on any student who asked a stupid question, made “bonehead” actions, or uttered a stupid comment. Too, with the money that was collected going to the waitresses in the hotel where the students ate, the practice not only made an impression on the students but also helped highlight the relationship between baseball and the local community.36

In that same vein, as part of their broad-based efforts to fully prepare and train their students for the rigors and realities of umpiring in the world of professional baseball, the school leaders would often get creative in their efforts to identify and help develop the more intangible professional talents, the character attributes, and attitudes that give one the ability to command the respect needed to control the game, things that cannot necessarily be taught but are critical to success as an umpires. Illustrative of that effort was a story Joe Brinkman told about a student at his school who had clearly been one of the top participants in his class but who, in the middle of the final exam, turned to him and made an obscene gesture. Brinkman was dumbfounded at witnessing such an unprecedented act of defiance. And yet he could not overlook the fact that the student was one of the very best prospects in the class. Events came to a head on the final night when the offending student was left off the list of those students who would be recommended for positions in minor-league baseball. As people congratulated each other, the forlorn rebel sat alone, unbelieving. But as people began to exit, Brinkman announced that he had left out a name, announcing that the offending party was also on the list of recommended aspirants. Brinkman recalled that he was sure the message had been received, noting that the humbled rookie went on to have a great year.37

Similarly, Brinkman also recounted another time when, in conjunction with the restaurant, he had an additional $10 put on each student’s bill at the end of one dinner. Brinkman recalled that while there was lots of grumbling among the prospective umps, no one directly asked the waitress about the overcharge; Brinkman later said he thought that perhaps his charges did not want to make a scene for fear of embarrassing him, and admitted that he was not sure what kind of reaction he was expecting, but he did believe that such efforts helped the prospective umpires learn how to react appropriately to unexpected situations.38 Such exercises and efforts were thought valuable in the never-ending efforts to help craft the attitude, approach, and demeanor necessary to handle a complaining player or maintain control of a game. In the heat of competition, those attributes were as important as a comprehensive command of the rules and the other technical aspects of the profession.

A Highly Competitive Process

Of course while the umpire schools provided the training, the process of becoming a major-league umpire is a highly competitive one, requiring skills and talents that oftentimes could not be taught. Consequently, attending a school has never guaranteed a career in umpiring and, in fact, in addition to their instructional role, the schools have long served as a winnowing process. Each year only the top students in each class at each school earn the opportunity to move on, starting at some level in the minor leagues, the only place where real attrition occurs as prospective big-league umpires’ work is assessed, and they move up or, with insufficient progress, wash out. Bill Kinnamon recalled that “McGowan made it clear the competition for advancement would be keen. He always said that if you weren’t the best umpire in your league, you wouldn’t move to a higher classification.”39 Indeed, there is no denying that the world of professional umpiring is highly competitive, with only a very few openings occurring each year. Former minor-league Umpire Development Director Mike Fitzpatrick noted that despite the fact that there are only 68 major-league umpires and around 225 in the minor leagues, and openings for new umpires are extremely limited, the two certified schools still enrolled approximately 300 aspiring umpires each year.40 Quite simply, as Fitzpatrick noted candidly, “it’s long odds.”41

Many attendees have no intention of becoming a professional umpire, but instead want to prepare themselves for amateur baseball — for instance, youth, high-school, and college umpiring.

Beyond its role in developing new umpires, the schools do have one other, often overlooked role, one that, however unintentionally, helps fill their instructional staffs. And that is the way veteran umpires see the sessions as a way to sharpen their skills and prepare for the coming season. Notable among those who felt that way was Bill Kinnamon, who worked as an instructor under McGowan, his son, and Al Somers after he took over the school.42 And of course school leaders like Brinkman and Wendelstedt also spent many years as instructors before they assumed ownership of their schools.

Impact of the Schools

With all modern umpires being graduates of the recognized umpiring schools, the question has arisen about the impact of the schools on the umpiring profession and the way modern umpires differ from their less formally trained predecessors. First and foremost, by all accounts the graduates of the schools have been far more knowledgeable about the rules of the game than their counterparts. At the same time, there has been an increased uniformity in their styles, as modern students, who have been taught, in some cases literally, “by the book,” are less apt to develop a distinctive style. Indeed, the whole formalized educational process has served, however unintentionally, to tone down the potential big personalities and filter out those who might have been mavericks, a somewhat interesting irony given that for all his professionalism and the respect with which he was held, McGowan, an author of one of the “books,” was certainly regarded as having a distinctive style and a personality that was as important to his ability to keep control of the game as his experience or his command of the rules.43

Another impact of the schools on the process has been the change in the prospective candidates. The formal training now required, coupled with the attendant career development, has given the profession a greater sheen of professionalism and as a result it has begun to attract a wider range of prospects. In transitioning from what was formerly viewed as an avocation into a vocation, a true profession, umpiring now attracts more middle-class candidates and college graduates, people who see umpiring as a distinctive and worthy career. This view represents a marked contrast to the previous view that saw umpiring as little more than a way for former players and others to simply remain involved with the sport.44 Indeed, attendance at an approved umpire school is not only at the top of a list of requirements for aspiring umpires that also includes a high-school diploma or a GED, reasonable body weight, 20/20 vision with or without glasses, good communication skills, quick reflexes and good coordination, and basic athletic ability. It is also something that has clearly added to the stature and to the respect umpires are accorded by the public and members of the professional baseball community.45

Looking Ahead

No one would deny that the game of baseball is deeply rooted in history, but that has not prevented it from changing, however slow that change has sometimes been. Umpires are certainly not immune to those changes. Indeed, things like instant replay and other types of technology have become accepted parts of the game and their use is expanding. At the same time, the umpires union’s ongoing efforts are impacting both working conditions and workloads. These newly achieved work rules have gone so far as to impact the culture of the game, disturbing some of the old umpire-team approach that added a certain stability, if one sometimes affected by fatigue. In the midst of all these changes, questions are sometimes raised about the education and training that umpires receive. But for now, the basic instructional approach pioneered by veteran umpires George Barr and Bill McGowan more than three-quarters of a century ago remain in place, offering a distinctive form of training for those who have been entrusted almost since the beginning with the oversight and the protection of the integrity of the game. Any changes to its approach must address the question of whether it will allow the umpires to better discharge their fundamental responsibility — the protection of the character and integrity of the game. In the end, it is that — the duty of the umpire to, as John Roberts put it, “make sure everybody plays by the rules” — to which everything pertaining to their training and responsibilities must point.46

BILL PRUDEN has been a teacher and administrator, primarily at the high school level, for almost 35 years. A SABR member since 2001, he has contributed to both the Bio and Games Projects. A lifetime baseball fan, he also loves to read, research, and write American History of all kinds, passions undoubtedly fueled by the fact that as a 7-year-old, at only his second major-league game, he witnessed Roger Maris hit his historic 61st home run.

Notes

1 “Roberts: ‘My job is to call balls and strikes and not to pitch or bat,’” CNN.com, September 12, 2005; cnn.com/2005/POLITICS/09/12/roberts.statement/.

2 “Roberts.

3 Larry R. Gerlach, Men in Blue, Conversations with Umpires (New York: Viking Press, 1980); The portraits in Gerlach’s book offer some interesting examples of the somewhat haphazard ways in which pre-school umpires entered the profession and ultimately arrived in the major leagues.

4 George Barr Umpire School,” Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia; arkbaseball.com/tiki-index.php?page=George+Barr+Umpire+School.

5 Bob Luke, Dean of Umpires: A Biography of Bill McGowan, 1896-1954 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, 2005), 87-88. Many authorities date the start of McGowan’s school to January 1939, but according to Luke, McGowan had conducted a short session in November 1938 with practical experience from umpiring University of Maryland games. In January he set up shop in Jackson, Mississippi, but after a couple weeks moved to Florida.

6 Bruce Weber, As They See ’Em, A Fan’s Travels in the Land of Umpires (New York: Scribner, 2009), 50.

7 “George Barr Umpire School,” Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia.

8 Ryan Aber, “Part of Major League History Finds Home in Guthrie,” NewsOK.com, May 6, 2013; newsok.com/article/3806892; Mark Blaeuer, “Reaching for the Brass Ring: A Portrait of Doan’s 1937 Baseball School,” Historic Baseball Trail, Hot Springs, Arkansas; hotspringsbaseballtrail.com/untold-stories/reaching-brass-ring-portrait-doans-1937-baseball-school/; “George Barr Umpire School,” Tulsa Historical Society & Museum; tulsahistory.pastperfectonline.com/photo/C2D2A68F-C8B9-483A-A874-454432539760.

9 Gerlach, 219. While he initially settled in Orlando when he moved to Florida, at various points Barr’s school operated out of Sanford and Longwood.

10 Luke, 103-106.

11 Bruce Weber, “Harry Wendelstedt, Umpire in Five World Series, Dies at 73,” New York Times, March 9, 2012: D8.

12 Weber, 50.

13 Ibid.

14 Kevin Hennessy, “Joe Brinkman,” SABR BioProject, sabr.org/bioproj/person/62a6e3cc.

15 Weber, 50.

16 Weber, 51.

17 Harold Uhlman, “Beating the Odds — An Umpire’s Near Impossible Road to the Majors,” ThinkBlueLA.com, November 19, 2015; thinkbluela.com/index.php/2015/11/19/beating-the-odds-an-umpires-near-impossible-road-to-the-majors-2/.

18 Minor League Baseball Umpire Training Academy; milbumpireacademy.com/default.aspx.

19 Andrew Keh, “For Umpiring School, a Staff Party Proves Costly,” New York Times, February 9, 2012; nytimes.com/2012/02/10/sports/baseball/umpiring-school-loses-baseball-relationship-over-behavior-at-party.html.

20 “About the Academy,” Jim Evans’ Academy of Professional Umpiring; umpireacademy.com/aboutacademy.php.

21 Luke, 92-93.

22 Matt Schudel, “Life’s a Pitch,” Sun-Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale, Florida), March 26, 1989; articles.sun-sentinel.com/1989-03-26/features/8901160574_1_professional-umpire-two-umpires-umpire-development.

For some insight into how the game as seen by an umpire is different and what thinking like an umpire might really mean as they go they do their job, see Dan Boyle et al., “Observations of Umpires at Work,” The Baseball Research Journal 40, no. 1 (Spring 2011): 77-87, an interesting article that recounts the results of an experiment conducted by seven SABR members who watched only the umpires during a game. The article offers some real insight into their work — and what they schools are preparing them for.

23 Schudel, “Life’s a Pitch.”

24 Luke, 135-187.

25 Gerlach, 253.

26 Martha Smilgis, “Act Up in Al Somers’ Class and You Get Sent to the Shower,” People, 9, No. 8 (February 27, 1978); people.com/people/archive/article/0,,20070277,00.html.

27 Ibid.

28 “About the Academy,” Jim Evans’ Academy of Professional Umpiring; umpireacademy.com/aboutacademy.php.

29 Weber, 51.

30 Ibid.

31 Weber, 51-51.

32 “How to Become an Umpire”; mlb.mlb.com/mlb/official_info/umpires/how_to_become.jsp.

33 Doug Miller, “Aspiring Umpires’ Paths Start at Florida Schools,” MLB.com; m.mlb.com/news/article/26485860/.

34 2013 Umpire School, 2013 Umpire School Experience, Day;

2013umpireschool.wordpress.com/.

35 Ibid.

36 “Student Umpires Fined for ‘Boners,’” Milwaukee Journal, March 14, 1939; news.google.com/newspapers?id=-qVQAAAAIBAJ&sjid=MCIEAAAAIBAJ&pg=2739,4069523&dq=george+barr+umpire&hl=en.

37 Angelo Cataldi, “Aspiring Umps: Only the Strong Survive,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 19, 1989; articles.philly.com/1989-02-19/sports/26153452_1_professional-umpire-young-umpire-joe-brinkman-umpire-school.

38 Ibid.

39 Gerlach, 237.

40 “How to Become an Umpire”; mlb.mlb.com/mlb/official_info/umpires/how_to_become.jsp. With the advent of instant replay, the number of major-league umpires is now 76.

41 Mike Couzens, “Chasing A Dream: Being an Umpire in Minor League Baseball,” August 26, 2013; mikecouzens.com/2013/08/26/chasing-a-dream-being-an-umpire-in-minor-league-baseball/.

42 Gerlach, 238.

43 “The History of Umpiring,” Hernando Sumpter Umpires; hernandosumterumpire.com/HISTORY.html. For a full sense of the way Bill McGowan did his job, as well as his multifaceted influence on the umpiring profession, see Luke, Dean of Umpires.

44 Ibid.

45 “How to Become an Umpire.”

46 “Roberts: ‘My job is to call balls and strikes and not to pitch or bat.’”