Wallace Goldsmith, Boston Sports Cartoonist

This article was written by Ed Brackett

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 26, 2006)

While searching through the pages of the Boston Globe from the years 1905 through 1920, I noticed a particular feature of the baseball coverage that you don’t see today, the use of a cartoon to accompany the written account of a game. It was suggested to me that perhaps a cartoonist was employed due to the lack of photographs in the sports pages of that era. I can agree with that to some degree; however, I am of the opinion that they were used primarily to provide a different perspective to the reporting of the games.

The reporter’s job was to produce a detailed account of the game’s proceedings. He had virtually unlimited space to create a complete description of the game. If a team was to score 25 runs, the reader would get a description of how each one crossed the plate. The story would be written in his personal style, but it is still a narrative of all the significant plays and events to give the reader the entire story.

The cartoonist, on the other hand, had a limited space in which to create his work, so he had to make a condensed version of the story. Because the scenes depicted were entirely of his choosing, he created an interpretation of the game that resulted in a summary more like that of a fan than reporter. The artist also had the power to satirize, and it was a duty which he seemed to relish. For example, an umpire will be drawn with daggers coming out of his eyes as he’s arguing with a player. On a play in which a fielder hopelessly misplays a batted ball, he will be shown in a confrontation with a baseball that has come to life saying, “You can’t catch me.”

Wallace Goldsmith produced cartoons for the Boston Globe from 1909 to 1919, and his creations were primarily of sporting topics. The subjects he covered were numerous, with the competition levels ranging from the local schoolboy to the professional ranks. Aside from his work of sporting subjects, he created editorial cartoons of Boston city politics as well as national issues such as the women’s suffrage movement or President Wilson’s foreign policies. He also made cartoons of local interest such as scenes from around the city on a record hot day or the winning species from the Boston poultry and dog shows. His work in this genre would compare favorably to any artist who specialized in political cartoons and would do so today if created using current topics.

He was the creator of a comic strip whose main character, Mr. Asa Spades, is a bumbling black man who gets caught up in adventures that revolved around the events of the day. This is an item that certainly wouldn’t be published today, but in an advertisement from 1910 it was hailed as a cartoon that “should be read by every man, woman and child in New England.”

The main focus of Mr. Goldsmith’s work was the coverage of the Red Sox and Braves. He traveled with the Red Sox to the spring training destinations of Hot Springs, Arkansas, and Redondo Beach, California, to provide daily reports of the workouts. During the baseball season his cartoons were reviews of the previous day’s game for whichever team was playing at home in Boston. His cartoons usually consist of a large sketch that serves as a highlight of a thrilling play or sequence of plays which should allow the viewer to make an instant judgment of the game’s outcome. This large sketch is surrounded by three to six smaller sketches depicting some great plays and not so great plays, along with such incidental moments as a boisterous spectator in the stands or a park employee reclaiming a foul ball from a fan.

He was always among the corps of writers providing coverage of the World Series games. In an advertisement introducing the staff of reporters and experts covering the 1914 fall classic, here is the brief summary that accompanied his picture.

Everybody knows Goldsmith’s baseball cartoons and his cleverness in picturing happenings on the baseball field, and during the World Series no bit of humor will escape his eye.

When he draws a likeness of a ball player you know who it is, and his sketches of the champions will be characteristic attitudes truer to life than would be possible in any photograph. Goldsmith will see the crucial plays in every game and will picture them in his graphic and funny way.

As an indication that Mr. Goldsmith was considered an important member of the Boston Globe staff, I make reference to an ad for a contest open to local children to acquire new subscribers. The Globe published a list of different features as selling points for them to recommend to potential customers while canvassing their neighborhood. Among the various suggested columns and editorials were features that would be of interest to baseball fans, “the funny and graphic cartoons” of Wallace Goldsmith.

In an example of how writer Timothy Murnane and Wallace Goldsmith interpreted the same event, I refer to an incident reported on May 27, 1914, in a game between the Red Sox and Cleveland. There was a play at second base in which the Red Sox Del Gainor was tagged out by Napoleon Lajoie, a product of the hidden-ball trick. Umpires Jack Sheridan and Oliver Chill each made call reversals on the play and caused protests from both teams. Here is how Murnane reported the incident:

There was quite a mixup at the base, and when Umpire Jack Sheridan looked, he saw Lajoie holding the Boston runner off the base and declared him out. This caused a sharp cry of protest from the Boston players, who argued that Lajoie pushed Gainor off the base, and as Sheridan had been caught looking anywhere but where the ball was he turned to the umpire at the plate for advice.

Umpire Chill waved his hand, as much as to say that the man was safe. Then Sheridan turned around and waved Gainor safe. At this stage nearly the whole Cleveland outfit, headed by the irate Frenchman from Woonsocket headed for the umpire at the plate.

Chill evidently saw them coming, for he immediately changed his mind and commenced to wave the player out. Umpire Sheridan then made his third decision, and this time was in full accord with the umpire in charge of the game, the pair of them having made five decisions on one play and pulling a juicy bone about the size of Bunker Hill Monument.

The cartoon Goldsmith produced was titled ONE WAY TO UMPIRE: IF YOU DON’T SEE IT, GUESS IT. In it Lajoie is shown tagging a prostrate Gainor with base umpire Sheridan having his back to the play while he is dreaming of lying on the beach. Plate umpire Chill is looking away from the play, dreaming of women and saying, “How lovely the ladies look in their summer garb.”

I believe that Mr. Goldsmith created his best work in 1914, 1915, and 1916, so I have included examples from those years that will showcase his talent.

(Click image to enlarge)

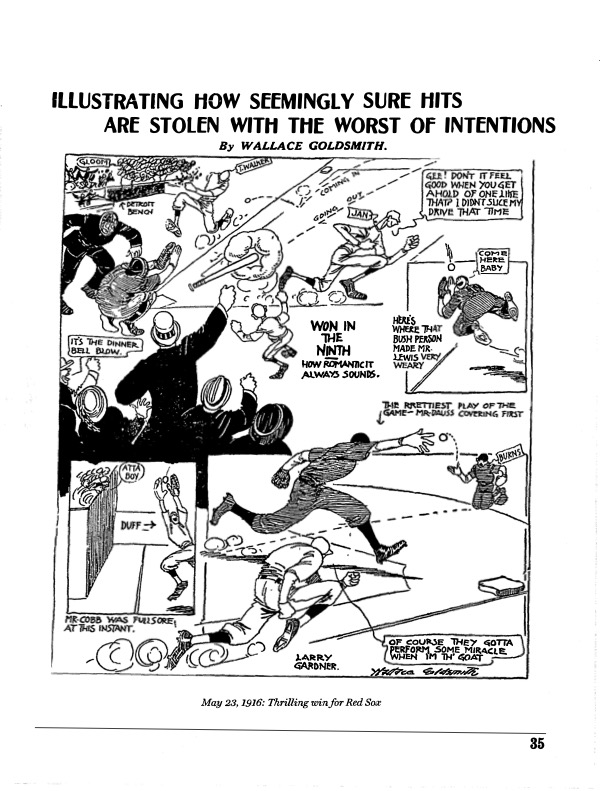

The cartoon from May 23, 1916, is what I consider a typical example of a game recap. This was a close game which was decided in the ninth inning when Tilly Walker scored on Harold Janvin’s single to left to give the Red Sox a 2-1 win over the Detroit Tigers. You will always notice certain distinguishing features utilizing a bit of artistic license. Smoke rings coming off a bat indicates a mighty blast or a puff of smoke off a glove means the fielding of a hot liner. Dotted lines track the flight of the ball; in this case you can see two examples of the ball leaving the bat and the return throw from a fielder. The players are constantly making some kind of statement, such as Janvin’s excitement over his hit or Gardner’s disappointment about his groundout. The fans have something to say also, the gent shouting, “It’s the dinner bell blow” certainly lets us know that the hit has ended the game.

(Click image to enlarge)

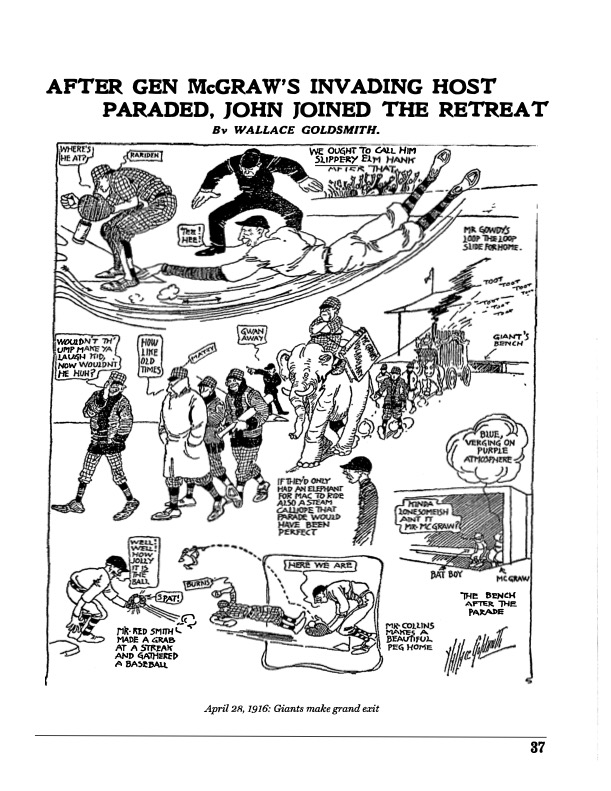

The main element of a Goldsmith cartoon is his use of humor and sarcasm, especially when used to show the ineptitude of the opposing team. The cartoon from April 28, 1916, reviews a game in which the Braves defeated the Giants 3-2. The incident to poke fun at occurred in the fifth inning when umpire Bill Klem was so annoyed by the chatter coming from the New York bench that he banished all players to the dressing room. Only manager John McGraw and the batboy were allowed to remain in the dugout as shown in the small sketch. The scene of the players filing out across the field is portrayed as a parade with McGraw riding atop an elephant and the whole group being trailed by a circus wagon. In the sixth inning, John McGraw was ejected for using offensive language, apparently taken from the book he is holding, titled “McGraw’s Vocabulary.”

(Click image to enlarge)

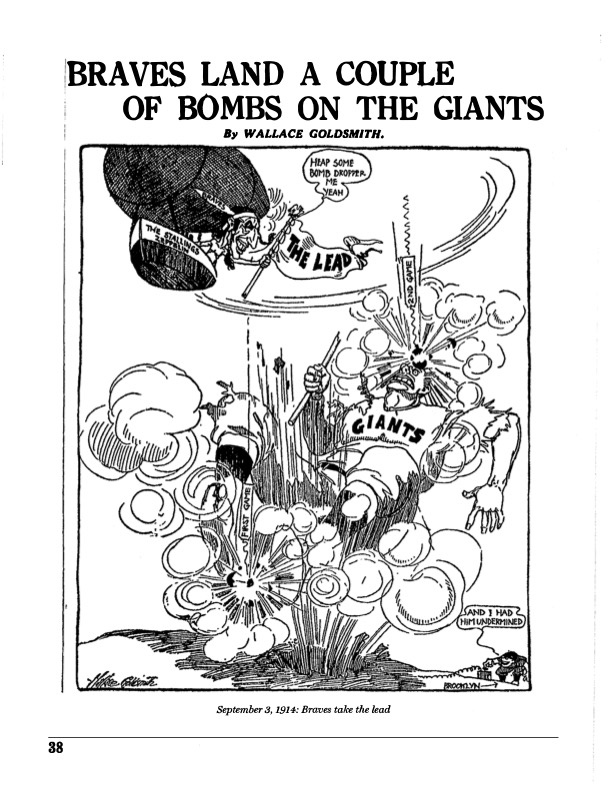

While the battles of World War I were being fought in Europe, Mr. Goldsmith often integrated a war theme into his work. The cartoon from September 3, 1914, illustrates when the Miracle Braves took the lead in the pennant race. A Brave is overhead snatching the flag from the New York Giants in an airship named “The Stallings Zeppelin” in reference to the Boston manager George Stallings. He is dropping two bombs, one labeled first game and the other labeled second game, which represents the Braves winning both ends of a doubleheader from the Phillies. In the background is a Brooklyn player setting off a mine, signifying their win over the Giants, all events which combined to cause the change in the standings.

In the cartoon that appeared on May 16, 1915, an Indian is shown getting blasted out of his canoe by a torpedo launched from a submarine piloted by a Pirate. You will notice that the canoe is named “9th” and the torpedo is labeled “6 hits in a row.” In this game the Braves were leading Pittsburgh by a score of 6 to 4 when, in the ninth inning, the Pirates had a string of six consecutive hits and scored six runs to eventually win the game 10-6.

Equipment was often fashioned as weaponry, as in a cartoon from April 18, 1916, which shows Walter Johnson getting shot to pieces by a Gatling gun with barrels made of baseball bats. In that game the Red Sox batters tagged Johnson for 11 hits in his six innings of work, and Boston won by a score of 5-1.

One feature of the cartoons that really made an impression that this was a different era is the complete lack of political correctness and portrayals of seemingly acceptable stereotypes. There are many humiliating representations of Native Americans. When the Boston Braves won, they were shown as Indians on the warpath, shooting arrows at a foe or wielding knives and tomahawks. When they lost, they were the poor souls who have been relocated to a reservation, bent over a campfire with an empty pot hanging over it.

During the war years players of German descent were sometimes pictured with spiked helmets like the ones worn by the German soldiers in the trenches of France. In the cartoon from May 26, 1915, Cincinnati’s players Buck Herzog, Fritz Von Kolnitz, and Fritz Mollwitz are shown in this capacity and acting quite militaristic in the sketch where they are ordering the ball to roll foul.

I believe that you really must admire Wallace Goldsmith’s portfolio of work at the Boston Globe. His cartoons reviewing the Red Sox and Braves games are impressive because he produced these pieces on a daily basis with each one being a unique and clever essay of the game. He was truly an imaginative and talented man.

ED BRACKETT is a Cad Designer for Atrium Medical Corp. in Hudson, New Hampshire. He is a member of the Massachusetts Baseball Umpire Association and can be seen calling games in the Merrimac Valley. This is his first article published by SABR.