Warren Spahn’s Insane Stats at the Twain

This article was written by Randy S. Robbins

This article was published in Fall 2020 Baseball Research Journal

As a young southpaw, I naturally felt an affinity for major league left-handers. Lefties, by nature, are outsiders. The consensus of sources spanning more than three decades states that only about 10 percent of the population is left-handed, making we portsiders indeed a rare breed.1 I, personally, never experienced the forced switching of penmanship meant to “cleanse” left-handed schoolchildren of earlier generations—a barbaric act harmful to one’s self-esteem, if not to the wiring of the brain itself. However, I was encouraged to slant my lined paper at a right-hander’s angle. And many a classroom offered a dearth of one-piece desks built for left-handers, my left elbow hanging humiliatingly in midair while my “normal-handed” classmates wrote in fully supported olecranal luxury.

As a young southpaw, I naturally felt an affinity for major league left-handers. Lefties, by nature, are outsiders. The consensus of sources spanning more than three decades states that only about 10 percent of the population is left-handed, making we portsiders indeed a rare breed.1 I, personally, never experienced the forced switching of penmanship meant to “cleanse” left-handed schoolchildren of earlier generations—a barbaric act harmful to one’s self-esteem, if not to the wiring of the brain itself. However, I was encouraged to slant my lined paper at a right-hander’s angle. And many a classroom offered a dearth of one-piece desks built for left-handers, my left elbow hanging humiliatingly in midair while my “normal-handed” classmates wrote in fully supported olecranal luxury.

When you’re left-handed, it dominates your whole being in a way that the majority of the world cannot understand simply because the world is fitted to them.

Still, even from a young age, I was told that baseball teams are forever on the lookout for left-handers who can throw with control, which made me feel special, even if my backyard catches with Dad hadn’t yet graduated from tennis ball to horsehide.

Thus, it’s no surprise that I felt an innate connection to southpaws who took the mound at Veterans Stadium, on television, and on my baseball cards: hometown Phillies Steve “Lefty” Carlton, Tug McGraw, Jim Kaat, and Randy Lerch (a lefty with my name!), Randy Jones (a Cy Young–winning lefty with my name!), Don Gullett, Mickey Lolich, Fred Norman, Paul Splittorff, Frank Tanana, Jerry Koosman. And, of course, the deity of all southpaws, Sandy Koufax, who, though just before my time, commanded the highest respect in my household because the electrifying southpaw, by virtue of his Jewish heritage, single-handedly revived my Flatbush-born father’s interest in baseball after his beloved Brooklyn Dodgers broke his heart. (Sadly, that renewed vigor for the game abandoned my father once and for all upon Koufax’s retirement.)

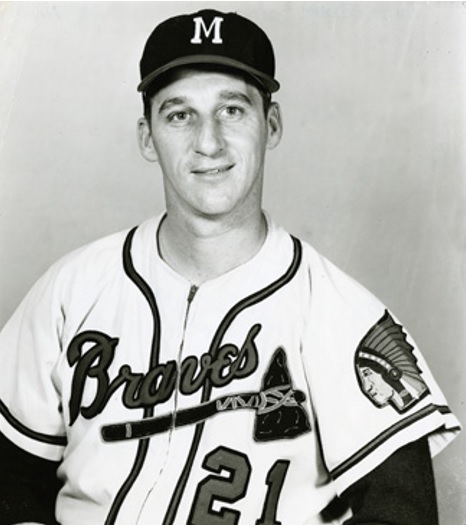

Of course, I also knew of the great lefties of old: Lefty Grove, Lefty Gomez, Eddie Plank, Carl Hubbell, even Babe Ruth himself! But the southpaw who loomed largest, of course, was Warren Spahn. One of my baseball magazines contained his lifetime record. Thirteen 20-win seasons. Thirteen?! And a win total, 363, to which no other lefty stood remotely close. For me, and perhaps other young southpaws, 363 became something akin to Babe Ruth’s 714 and Ty Cobb’s 4191 (before many sources revised his hit total to 4189), an instantly identifiable benchmark in baseball history that spoke for itself.

Yet in examining Spahn’s record more closely, one finds a statistic that should make one wonder beyond simple coincidence: During a career in which Spahn pitched 363 victories, the multitalented hurler also recorded 363 batting hits.

When one takes into account the myriad variables that go into this curious confluence—from the fact that a starting pitcher’s at-bats vary from game to game depending on how well his hurling keeps him in each contest, to the fact that Spahn relieved in 85 games, further fluctuating his at-bats—one further wonders how unusual this could be.

And then there’s the additional confounding variable that Spahn appeared in 18 games as a pinch-hitter, which chance could employ to further skew two totals rather than bring them together.

Macroscopically, how could one total derived from a pool of 750 (games) end up equaling another from a pool of 1872 (at-bats)—especially considering the first is accrued at a maximum of one per game whereas the second is almost always accrued multiple times per game?

It is for strange cases such as this that I wish I were a mathematician so that I could calculate the odds of two wholly unrelated totals, incurred at vastly different per-game rates (0 to 1 for wins; 0 to infinity for hits), somehow matching up perfectly over the course of 21 seasons. Still, it doesn’t leave me exactly hollow to state abstractly that the chance of both totals landing on 363 seem merely astronomical.

Yet, is it?

Among all pitchers with at least 100 victories, three others matched Spahn’s accomplishment: Dick Ruthven (123 wins/123 hits), Dave Roberts (103/103), and Tex Carleton (100/100).

Ten other pitchers had victory and hit totals separated by exactly 1, and 57 pitchers had a difference of between 2 and 10 (including Smoky Joe Wood’s tenure as a pitcher with Boston and Phil Niekro’s totals as a Brave, because he never batted for another franchise). These 70 other pitchers range from some of the most talented moundsmen ever, such as Grover Cleveland Alexander and Three Finger Brown, to the mediocre likes of Don Cardwell and Chuck Stobbs.

Whether one attributes it to less formidable pitching or to pitchers, themselves, possessing better-honed batting skills in a less specialized time, this seems largely to be a phenomenon of bygone days. Only five of these 70 pitchers played most or all of their career during the designated-hitter era, and none are active (although Madison Bumgarner had a difference of just 14 at the end of the 2019 season). Warren Spahn, however, took this statistical quirk to the next level.

One of the best batsmen among pitchers, the crafty Buffalonian possessed an uncanny (though surely unrecognized) knack for knocking as many hits in a season as he tossed victories. Eleven times, Warren’s win total of any given season equaled his hit total of any given season, including an incredible eight times in the same season. That is some serious synchronicity, if such a concept can be applied to the baseball diamond.

Yet there exists another layer to this algebraic madness. Spahn, who seemed as if he would continue winning forever, going 23–7 at age 42, finally was snared by Father Time in 1964. After suffering only his second losing campaign since breaking into the big leagues more than two decades earlier, he was purchased from Milwaukee by the young New York Mets just before Thanksgiving.

As the ledger closed on his Braves career, Spahn boasted 356 victories—again, the exact number of hits he notched as a Boston/Milwaukee Brave.

Struggling through 20 games with the ever-floundering Mets, Spahn staggered to a 4–12 record, his bloated 4.36 ERA hardly helping the punchless New Yorkers. Yet in those 20 games, as well as one in which he pinch-hit, Spahn collected four hits, equaling his victory total.

Going nowhere, New York released Spahn on July 17. Two days later, the San Francisco Giants, tangled in fourth place yet only 5½ games off the lead, signed Spahn, hoping to coax a last bit of magic from his left arm for the stretch drive. Perhaps revitalized by taking the mound once again for a contender, Spahn pitched better, for a time. As a Giant, he cut his ERA by nearly a run and chipped in three victories, although four of his last five appearances were spent in relief, as the Giants came up two games short at the wire.

Yet with eerie consistency, Spahn once again managed to collect as many hits as victories, rapping a trio of singles to match the 3–4 record he put up with San Francisco. The Giants released Spahn after the season, ending his remarkable major league career.

Not only had Spahn managed to produce equal victory and hit totals across 21 seasons (interestingly, he stroked his first hit in 1942 yet had to wait, because of highly decorated military service in World War II, until 1946 for his initial victory) but he, improbably, registered matching numbers of hits and victories with each franchise for which he played.

Warren even remained true to his nature in the postseason, slapping four singles to complement his four World Series victories.

Spahn’s peculiar proclivity was not exclusive to the major leagues. Between his pair of appearances at both the opening and closing of the 1942 season, his apprenticeship with the Hartford Bees of the Eastern League saw him register 17 hits en route to a team-leading 17 victories. And just for good measure, when Warren pitched seven innings over three games while managing the Pacific Coast League’s Tulsa Oilers in 1967, he failed to get a hit in four at-bats, matching the 0-1 record of his minor league swan song.

And if all that weren’t enough, the breakdown of Spahn’s corresponding pitching wins and batting hits achieved as a Brave by city very nearly match as well: As a Boston Brave, Spahn won 122 games while collecting 120 hits, which, of course, leaves his totals after the Braves moved to Milwaukee at 234 pitching wins and 236 hits.

(In pale reflections of Spahn’s strange achievement, Steve Carlton logged both 77 victories and hits as a St. Louis Cardinal, though his totals in Phillie pinstripes are significantly farther apart, whereas Curt Davis did the same for the Phillies but none of the other three teams for which he hurled. Joe McGinnity matched his league-leading 28 victories in each of his first two seasons with 28 hits during each campaign. Additionally, George Mogridge’s career included 68 wins and 68 hits for the Washington Senators, and General Crowder’s hit total is exactly one less than his victory total for each of the three teams for which he pitched.)

Warren Spahn’s almost preternatural ability to achieve pitching victories and batting hits with the same frequency on multiple “levels” seems to represent a true statistical anomaly in baseball annals.

Perhaps southpaws should take a bit of pointless pride that this odd phenomenon appears well suited to our “eccentric” minority: Of the 71 pitchers (including Spahn) with at least 100 victories and a difference of 10 or fewer between victories and batting hits, 26 (36.6%) were lefties—an amount noticeably higher than the 28.0%–29.7% of left-handed starters populating major league rosters since 1904.2

RANDY S. ROBBINS is a Philadelphia-area native who grew up a Big Red Machine fan before eventually converting to the hometown nine. He is obsessive about the game though he doesn’t much care for the recent turns baseball has taken. He worked as an editor in the medical and pharmaceutical fields for nearly 30 years and his own articles and op-eds (both sports- and non- sports-related, humorous and serious) have been published in numerous newspapers, magazines, and websites over the years. Despite once having driven Henry Aaron in his car, he considers his greatest moment in baseball to be the time a 60-something, Brooklyn-born umpire in a men’s league game, while observing him scooping low throws at first base between innings, told him he was reminded of Gil Hodges.

Notes

1 “World’s Biggest Study of Left-handedness.” NeuroscienceNews.com, April 3, 2020. https://neurosciencenews.com/left-handedness-study-16070/.

2 Mike Petriello. “Where Have All the Top Lefty Pitchers Gone?” MLB.com, May 20, 2020. https://www.mlb.com/news/left-handed-pitchers-decreasing.