Wartime Baseball: Minor Leagues, Major Changes From San Diego to Buffalo

This article was written by James D. Smith III

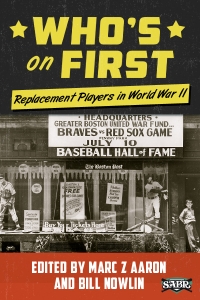

This article was published in Essays from Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II (2015)

Following the events of Pearl Harbor and in Europe, on January 15, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt responded to Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis: “I honestly feel it would be best for the country to keep baseball going.” Thus, through 1945, the heroic military efforts of Americans in World War II would be complemented and supported by the loyal hometown efforts of professional baseball teams and leagues.

There is a remarkable literature presenting this story (see Gary Bedingfield’s website: baseballinwartime.com); and the National World War II Museum’s 2007-08 exhibition in New Orleans, “When Baseball Went to War,” specially honored the era.1

While much of the attention rightfully has focused on the major-league scene, the economic impact of war mobilization “down on the farm” has often been ignored. There are statistics: in 1941 there were 41 minor leagues; by 1945 only 12 had survived. There are also stories: This essay focuses on the Pacific Coast League San Diego Padres during the last year of the war, and the resourcefulness of owner Bill Starr and his ever-changing team. Some notes on the Buffalo Bisons’ International League efforts are offered as well.

Brooklyn-born William “Chick” Starr (1911-91) began his “long affair with baseball” in 1919 White Sox-era Chicago, entered pro baseball at age 20 in the Nebraska State League, and spent five years in the minors before appearing in 13 major-league games as a backup catcher with the Washington Senators (1935-36). In 1937 he came west, as his contract was sold to the second-year San Diego Padres, whom he helped become PCL champions.

Starr’s playing career ended with a broken leg in 1939, and he became a successful local businessman. Also a fan, he followed the team into the war years – most fully described in Ray Brandes and Bill Swank’s 1997 book The Pacific Coast League San Diego Padres: Lane Field, The Early Years 1936-1946.2 In what Starr once told me was a matter of “both heart and head,” he moved to buy the team from the estate of its deceased owner (and his former boss), Bill “Hardrock” Lane, in 1944. The war was on, and he was on the spot. What would it take to survive?

Team members. As Starr related to me in a 1990 interview, “When I walked in to go to work, they’d cleaned out all the files. We had no records of any pending transactions. All I had was a list of the players and the payroll. It was really a bad situation. My test was to now find players. …”3 Continually, given armed forces personnel needs, Selective Service was a factor. “In 1945 I got a call from Pepper Martin, our manager, in Los Angeles: ‘I haven’t got anybody to play the infield – they’re all gone.’ I drove to Los Angeles, went to a playground, saw a kid who wouldn’t get hurt too bad, and said ‘Would you like to play for the Padres today?’ And I signed him.”4 The Padres used 52 players that year.

Think Young. Most are familiar with the signing of 15-year-old pitcher Joe Nuxhall by the Cincinnati Reds in 1944. In the minor leagues, the desperate PCL Los Angeles Angels had inked catcher Bill Sarni, age 15, the previous year. The Padres in 1944 took on 16-year-old shortstop Hank Sciarra: “I was playing semipro ball in LA and a scout named Jack Talbert saw me. I was really conned into it. It was tough on a 16-year-old kid to be with those older players. … I couldn’t go on the road in ’44 because I had to go to San Diego High School. It was the law, so I was going to school and playing professional baseball at the same time.”5

Try Moonlighting. Some players were able to continue playing pro ball if they supported the war effort in other ways. Padres first baseman/outfielder Lou Vezilich would recall: “1945 … I’ll never forget that year. Did manage to play every game, although I had only one week of spring training. The draft board had me go to work at Rohr Aircraft at the beginning of the season. … Getting to work at 7 A.M. and be[ing] ready for night games.”6 Vezilich, who led the PCL with 110 RBIs, was certainly not alone. Two years earlier, for example, veteran Buffalo pitcher Jack Tising had gone 13-20 while pitching between shifts at Bell Aircraft, and the following year went 6-10 while doing it again.

Take a Shot. Reflecting both compassion and practicality, some teams went the extra mile in reaching out to players with personal problems. Starr recalled a telegram. “One said, ‘I know one hell of a pitcher if you can get him out of jail: Vallie Eaves.’ He was an Indian, but a drunkard. A judge got him out and he won a lot of games for us. … Pepper Martin was a real tough guy and he was a very religious guy. … I said to him one day, ‘What can you do to keep this guy Vallie Eaves sober?’ The next time he saw him drunk, he just punched him and knocked him cold.” It worked – and Eaves won 21 games in 1945. Early the next year, the Dodgers’ Branch Rickey wanted to sign Eaves, following one more game. Starr excitedly communicated this opportunity to his pitcher – who that night got “wholly drunk” and was arrested throwing bottles from the hotel roof. In our interview, the owner said with emotion in his voice, “I often wondered if I made a mistake by telling him. …”7

The Ultimate Sacrifice. Every person, every player entering military service came from a community hoping for their return from battle to resume civilian life – sometimes baseball. In San Diego that included native son Ted Williams, but also less famous ballplayers like Manuel “Nay” Hernandez. “Nay” played on great San Diego High School teams, was a standout in local industrial leagues, and so struck 1944 Padres manager George Detore (Starr’s fellow catcher on the ’37 PCL champs) that he was the season’s starting left fielder. Initially, Selective Service rejected him due to a heart condition. Then, in the words of his sister Tina Hernandez, “He was drafted because the war was going bad. He was just a rookie. He had a murmur. They said if he’s good enough to play baseball, he can be in the Army. They put him in the infantry, and he didn’t last two months. He got killed in the Battle of the Bulge [March 22, 1945].”8 Less than two months later came the German surrender.

Meanwhile, in New York … After seeing the 1943 Buffalo team in spring training, rival manager Jewel Ens of Syracuse said it was the worst-looking ballclub he had ever seen.9 This reflected on International League play overall. Bison Shovels Kobesky did hit 18 home runs – and led the circuit. One regular, Gerald McNair, batted .186. At one point center fielder Mayo Smith went 0-for-34 and was cheered.

After an upturn in 1944, the 1945 team included 40 players from teenagers Billy Pierce, Art Houtteman, and Emery Hresko to 40-somethings Lloyd Brown and Ollie Carnegie – who at age 46 batted .301 against the tepid pitching. The left side of the infield was porous, as Herschel Held fielded .877 and shortstop Preston Gomez .919. The team went 64-89.

But World War II ended. It has been observed that most big leaguers did not serve in combat zones, though those such as Bob Feller certainly did. It was primarily the minor leaguer who saw the heat of action, and at least 130-200 died during the war. It was from the minors that heroes Jerry Coleman and Lou Brissie came.

The Aftermath. Bill Starr owned the PCL Padres through 1955, when he sold to C. Arnholt Smith, a banker who had risked capital to help finance the team’s wartime purchase. After 1945, he would sign veterans such as pitcher Bob Savage (a member of the Padres’ 1949-50 contenders), outfielder Earl Rapp (whose bat led the 1954 first-place PCL finishers), and Eddie Kazak (1955-58, batting .300 at old Lane Field and a final-year .334 at the new Westgate Park). One of Starr’s earliest postwar acquisitions was Chuck Eisenman (1946-47), an Army Signal Corps major who invented the movable mound used on English soccer fields, founded the London Central Base Clowns (43-4 against competition before D-Day), and went on to become a media celebrity.

Perhaps best remembered is San Diego native Johnny Ritchey, who earned five World War II battle ribbons and fought in the Battle of the Bulge – and then after the war returned to pro baseball segregation. After he led the Negro American League at .381 in 1947, Bill Starr signed him to a Padres contract, breaking the PCL color barrier. Ritchey dealt with the pressure by opening at a 7-for-11 pace, batting .323 for the 1948 season – and remaining a man of immense character. Starr told me in 1990 of the challenges: “But 1947 was the year Jackie Robinson came up. And I got to thinking, ‘What would happen if I searched out and found some capable black player?’ The Coast League was lily white and had some old-timers who were very critical of Branch Rickey. I thought it was kinda stupid. That’s how we got John Ritchey. Then we got Luke Easter. …”10

In his 1989 insider book, Clearing the Bases: Baseball Then & Now, Bill Starr reflected: “As an independent club we were able to compete for talent with the majors – perhaps at a disadvantage but, nevertheless, with some degree of success.”11 Though he did not serve in the military himself (his last deferment came in February 1945), as a baseball veteran he joined company with minor-league owners who resourcefully sustained the game (and hometown morale) throughout World War II.

JAMES D. SMITH III joined SABR in 1982, when wife Linda said he needed a hobby. With a Harvard doctorate in church history, he is professor at Bethel Seminary and associate pastor of La Jolla Christian fellowship. Three children, six grandchildren and studies/ministries in Boston and Minneapolis have inspired the San Diego natives as lifelong fans. Baseball research interests include the PCL Padres, 19th century ball and biography — especially Christians in baseball history. Jim has contributed to SABR’s BRJ, TNP, 19th Century Stars, Baseball’s First Stars and the SABR book. Other baseball essays have appeared in the Biographical Dictionary of American Sports, The Kid: Ted Williams in San Diego, NY Mets Inside Pitch, KC Baseball Review, Minneapolis Review of Baseball, Elysian Fields Quarterly, Sports Spectrum, The San Diego Padres: 1936-1957 and Echoes from Lane Field. Most of his books and articles, however, have engaged Christian history, biography and spirituality.

Notes

1 See also Todd W. Anton and Bill Nowlin, When Baseball Went to War (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2008).

2 Ray Brandes and Bill Swank, The Pacific Coast League San Diego Padres: Lane Field, The Early Years (San Diego: San Diego Padres and San Diego Baseball Historical Society, 1997), 1, 233-250.

3 Brandes and Swank.

4 Brandes and Swank.

5 Brandes and Swank. 59.

6 Brandes and Swank. 58.

7 Brandes and Swank, 36.

8 Bill Swank, Echoes from Lane Field (Paducah, Kentucky: Turner Publishing, 1997), 57. More accurately, he had been killed in the aftermath to the Battle of the Bulge.

9 milb.com/content/page.jsp?sid=t422&ymd=20080405&content_id=380903&vkey=team4.

10 Swank, 36.

11 Bill Starr, Clearing the Bases: Baseball Then & Now (New York: Michael Kesend Publishing, 1989), 8.