Wartime Baseball: Not That Bad

This article was written by Renwick W. Speer

This article was published in 1983 Baseball Research Journal

After the passing of nearly 40 years, as is the case since World War II, we are inclined to recall events differently than the way they really happened. Now, there’s nothing wrong with fantasizing a little or adding color to actual events, but the amount of distortion and misleading material that has been published in recent years on wartime baseball seems to be on the rise. For that reason there developed a compelling urge from within me to recall and seek out the facts concerning the quality of baseball as played in the major leagues during our great war in the 1 940s. After reading several of the recent features on this subject, I’m sure many fans of today conclude that the major league teams of 1942-1945 were 16 traveling comedy acts.

We have heard these “no talent” stories so often that we are inclined to accept them as fact without even asking for proof. Fact is, we doubt more and more that there is evidence of ineptness as we shall see by sifting thru the statistics of that era and comparing them with other periods.

Those too young to remember WWII years have no source of knowledge about the great American pastime other than to read what has been written by others. I must say that I recently read a book on baseball during the war years that was authored by a man who was only 11 years old when the war ended. I enjoyed the book and found it reasonably correct with facts; however, one aspect was missing. As in all other printed material which we have read on the subject, little or no recognition was given to those players who made it to the big leagues during the war and were talented enough to hold their places on the team rosters after hostilities ended and former players returned.

A more recent author goes so far as to use the phrase “stripped of talent” when describing the teams representing major league cities during WWII. His book was put aside when I discovered that he had no first-hand knowledge of anything contained in his publication. To my knowledge no such inaccuracies have been published by any adult eye witnesses to wartime baseball.

Too much emphasis has been placed on the negative, humorous and ridiculous side of wartime baseball and little, if any, on the positive and realistic accomplishments during the same period. I have heard and read all I ever want to know about players with one arm, one leg, deaf players, alcoholics, too young, too old – you name it; but nothing about the great athletes, leaders and personalities produced during those years. Also, this may be the first time many fans have been told that all the good players did not go off to war, take jobs in defense industry or on farms, as we are inclined to believe. Granted, Bob Feller, Hank Greenberg, Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio and other heroes of yours and mine were in military uniform, but what about the many outstanding players of that era who played all during the war? They will be listed later.

During the early days of the war, Congress debated whether to allow professional baseball to continue in operation and President Franklin Roosevelt agreed in 1942 that it would help to maintain morale at home and abroad if the game were permitted to continue. In a letter dated January 15, 1942, to Baseball Commissioner Kennesaw Landis, President Roosevelt said, “I honestly feel that it would be best for the country to keep baseball going” and “if 300 teams use 5,000 or 6,000 players, these players are a definite recreational asset to at least 20,000,000 of our fellow citizens.” I was delighted by that decision because the ball scores had been a highlight of each day. Also, it gave me an opportunity to see games when I was near New York City and Philadelphia areas, which was my pleasure many times from 1941 to 1945.

For the purposes of this article, we will define “war years” as 1942 through 1945. Those were the years (with 1942 being less severe) that teams were most affected by their players being absent in military service. Only a few, like Hugh Mulcahy and Hank Greenberg, served in 1941.

There were players, with less talent than we were accustomed to observing, who were brought up to fill rosters when the regulars volunteered or were drafted. These are the players who have kept some sports writers busy with stories about their antics and errors on the field. We devote only a small section to that group because they have had their day in print; then faded quickly in 1946 when the regulars returned.

As mentioned earlier, there were many quality players whose names should be familiar to most fans who did not miss a full season during the war years. Here is a partial list in that category: Lou Boudreau, Walker Cooper, Pete Coscarart, Frank Crosetti, Roy Cullenbine, Babe Dahlgren, Phil Cavarretta, Bob Elliott, Nick Etten, Rick Ferrell, Augie Galan, Frankie Gustine, Stan Hack, Frankie Flayes, Jeff Heath, Bob Johnson, Johnny Hopp, Joe Kuhel, Whitey Kurowski, Chet Laabs, Johnny Lindell, Al Lopez, Marty Marion, Phil Masi, Joe Medwick, Frank McCormick, George McQuinn, Eddie Miller, Wally Moses, Mel Ott, Bill Nicholson, Ken O’Day, Mickey Gwen, Paul Richards, Buddy Rosar, Dick Siebert, Vern Stephens, Snuffy Stirnweiss, Mike Tresh, Bob Swift, Dixie Walker, Gee Walker, Jimmy Wasdell, and Rudy York.

Some pretty fair talent, wouldn’t you say?

And now for the pitchers in that same category, i.e., those who didn’t miss one full season during the war: Jim Bagby, Ernie Bonham, Hank Borowy, Max Butcher, Alex Carrasquel, Spud Chandler, Mort Cooper, Curt Davis, Paul Derringer, Bill Dietrich, Atley Donald, Harry Feldman, Steve Gromek, Orval Grove, Mel Harder, Joe Haynes, Joe Heving, Al Hollingsworth, John Humphries, Oscar Judd, Vern Kennedy, Max Lanier, Bill Lee, Thornton Lee, Dutch Leonard, Bob Muncrief, Hal Newhouser, Bobo Newsom, Johnny Niggeling, Fritz Ostermueller, Claude Passeau, Elmer Riddle, Preacher Roe, Mike Ryba, Rip Sewell, Al Smith, Jim Tobin, Dizzy Trout, Jim Turner, Bucky Walters, and Whitlow Wyatt.

That list almost resembles Who’s Who for pitchers of that era.

To emphasize further that the quality of major league ball was not diluted as much as we are being told, here is a list of quality players who were absent from their teams for only one complete season: Bobby Doerr, Debs Garms, Rollie Hemsley, Pinky Higgins, Myril Hoag, Eddie Joost, Charlie Keller, Danny Litwhiler, Stan Musial and Ron Northey. Pitchers who missed only one season include: Joe Beggs, Harry Gumbert, Tex Hughson, Van Lingle Mungo, Ken Raffensberger, Clyde Shoun and Early Wynn.

The temptation now is to honor those who lost more than one year from their playing careers; however; we said that our purpose is to show that there was still real quality in big league play during WWII. In that regard, let us state for the record that Hugh Mulcahy was the first major leaguer inducted into the Army under the draft in 1941. Bad luck was nothing new to Mulcahy who had been a good pitcher with a very poor team.

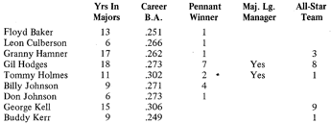

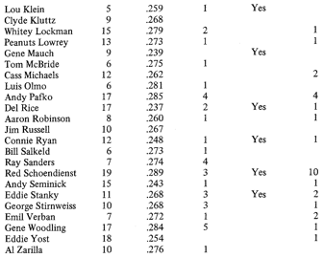

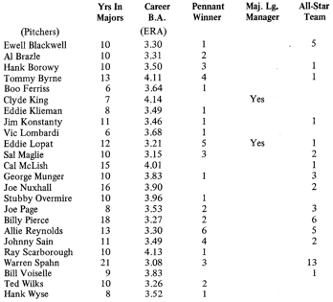

Of the several categories of players during the war years, there is one very important one we have continued to neglect: Those who made it to the top during the years 1942-45 and were talented enough to continue in the majors after the stars and regulars returned from military service. There follows a partial list of perhaps the more familiar names. All of them either played on a pennant winner, were selected for the All-Star team, or became a major league manager.

(Click images to enlarge)

When checking over our wartime players’ list, we found that 45 played on one or more pennant winners, 10 became major league managers, and 34 were selected to one or more All-Star teams. A more impressive list could have been compiled had we not been so restrictive with the 1942-45 rule. Preacher Roe came to the majors to stay in 1944 but does not qualify for our list because he pitched three innings for the Cardinals in 1938. Woody Williams moved up to the Reds in 1943 where he tied the NL record with ten consecutive hits, but he also is disqualified because he played in 20 games for the Dodgers back in 1938. There are other similar cases.

There was some interesting play and many good performances during WWII. Relief pitching, led by Ace Adams of the Giants, became a more important part of the game; base stealing was revived by George Case, George Stirnweiss, and veteran Wally Moses; there was less dependence on the home run, and more use of the hit-and-run. Eddie Stanky set a NL record with 148 walks in 1945; Snuffy Stirnweiss hit 22 triples in 1945, the highest mark in 15 years; Hal Newhouser and Dizzy Trout won 29 and 27 games respectively for the Tigers in 1944, the best two-man effort in many years; the home run might have been downgraded, but not discarded: Pitcher Jim Tobin hit three in one game in I 942; Vince DiMaggio hit four grand slams in an injury-shortened season for the Phils in 1945; in 1944, Lou Boudreau led the AL in batting and the shortstops in fielding; in 1945, Tommy Holmes hit in 37 consecutive games, a modern NL record, since surpassed; that same year he led the league with 28 home runs and the fewest strikeouts (9), a remarkable combination for any era. To conclude this portion, we must note that George Kell, a wartime player by definition, was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1983.

Oh sure, there are some truly wartime players, i.e., those whose playing time in the majors was limited strictly to 1942-45 but haven’t there always been players who made it to the top, only to play a few innings and fade? Here are some wartime players who have made great copy over the years:

Mike Garbark: Mike shared the catching duties for the Yankees in 1944 and `45 with Rollie Hemsley and Aaron Robinson. Hemsley was 37 years old and had been catching in the big leagues for 16 years while Robinson was a newcomer. It was Garbark who seemed to get most of the sporting ink and attention. Fans today remember Mike for once going 0 for 49, but in 1944 he hit .261 and caught 85 games for the Yankees. Quite respectable stats by today’s standards.

Danny Gardella: His name always surfaces when wartime baseball is mentioned. Gardella, a New York Giant outfielder, became well known for being struck on the head by a baseball that he was supposed to catch. He did, however, hit .272 and 28 home runs in 121 games in 1945 – better than some free agents.

Joe Nuxhall: The youngest player ever to appear in a major league! He was 15 years old and had been pitching for his junior high school two weeks prior to his big league debut with Cincinnati in 1944. A recent author, when writing about wartime baseball, devoted nearly three pages and a picture of Nuxhall in his book. The question that immediately comes to mind is, “What possible impact did Joe Nuxhall have on wartime ball when his total experience in the major leagues during 1942-45 was two-thirds of one inning; and that was in a game which was hopelessly lost?” Joe entered the game in the ninth inning with his team behind 13-0. It’s good that Manager Bill McKechnie used Joe Nuxhall for that 2/3 of an inning in 1944 because that qualifies Joe as a wartime player. He returned to the majors eight years later and remained for 15 more, and 135 wins.

Dick Sipek: Dick was a deaf player who was brought up by the Reds in 1945 and appeared in the lineup 82 games as an outfielder or pinch hitter. He had hit .336 and .319 for Birmingham in the Southern Association in 1943 and 1944. Now we hear about the “deaf player in the major leagues during the war” but what about Dummy Hoy who played in 1798 big league games over 14 years with a lifetime BA of .288? Also, there was Luther “Dummy” Taylor who pitched nine seasons for the New York Giants and Cleveland Indians and won 117 games. Handicapped players have always progressed as far as their talents would take them so we must be careful not to attribute their success to a war when they make it to the top.

Pete Gray: This is the player most often mentioned by today’s writers and fans when they discuss wartime baseball. Pete, as most of you know, had only one arm and played the outfield for the St. Louis Browns in 1945, but many don’t realize that he was a regular for Memphis in the Southern Association in 1943 and `44 where, in his second year, he hit .333, stole 63 bases, led the outfielders in fielding percentage and was voted MVP. That is what qualified Pete for a shot at the big time; not the loss of an arm. Pete Gray’s entire major league career consisted of 61 games in the outfield and 12 as a pinch hitter in 1945 – less than one-half of the Browns’ schedule for the season. Some who never saw him play or were little children when they did, have published stories which imply that Pete Gray was typical of the era. This misinforms the modern-day fan of the true conditions in baseball during the war years.

It was six years after WWII when Eddie Gaedel, a 65 lb., 3’7″ midget officially entered a major league game and drew a base on balls. If that had happened during the war, we believe that volumes would have been printed about the event attributing it to player shortage and poor quality of the game resulting from the war.

Our point is, war or no war, the “gate attraction” player has always been used as a part of baseball and we agree that it has been good for the game and should continue, on occasion.

Even a noted columnist like Joe Falls, when writing about the war years in The Sporting News, June 28, 1980, included the names Tony Lupien, Creepy Crespi, Cliff Melton Nick Etten, Johnny Sturm, Phil Weintraub, Granny Hamner and others when attempting to be humorous about wartime ball. Let’s just look at the records of some of these “great names,” as they were jokingly referred to by our columnist. You can see that there is no way that they can be classified as wartime players, under his own definition.

Tony Lupien made it to the majors in 1940, two years before the USA entered WWII, and he was still good enough to play in all 154 games for the White Sox as late as 1948, three years after the war ended. Creepy Crespi’s major league career ended in 1942, or one year before what the columnist himself defines as wartime ball.

Cliff Melton pitched for the New York Giants in 1944 and 1945, but he had been with them since 1947 and won 20 games with an earned run average of 2.61 his rookie year. Phil Weintraub also played in five seasons of major league ball prior to the war.

Nick Etten advanced to the majors in 1938 and hit .311 with 14 home runs in the National League as early as 1941. Many only remember him as the Yankee first baseman during the war but he remained in the majors until 1947.

Johnny Sturm was the Yankee regular first baseman for the 1941 season when his team won the World Series. Joining the military before the 1942 season, Sturm was injured and never played in another major league game. How can his name be associated with wartime baseball?

Granny Hamner had an outstanding career of 17 years in the big leagues; is any explanation necessary as to why he wouldn’t be classified as a wartime player? We will, however, accept his older brother Garvin under that category because he came up to the Phillies in 1945 for 32 games, got 20 hits for a .198 BA. That was Garvin’s total major league career.

It is not our purpose to single out one sportswriter because many have gotten plenty of mileage from stories about the war years, but we find it necessary to be specific on occasions, otherwise our information would be open to the same criticism.

If the policy of accuracy is not exercised, what will be printed about the quality of baseball during the “expansion years” when the number of major league teams increased from 16 to 26 and the Mets won only 40 games while Roger Craig lost 24. Several teams consistently lost over 100 games in a season and the Yankees finished dead last with a 20-game losing pitcher in the 10-team expanded American League. Let us hasten to say that no one is advocating that any of the 10 expansion teams be removed from the majors, but, just imagine the rise in quality of play if the 250 players with the poorest records were removed from club rosters and all remaining players regrouped back to 16 teams?

Well, this comparison could, and will, continue for years but we are not conducting a study on player ability in expansion baseball; that perhaps will be done some 20-3 0 years down the road.

We maintain that a good brand of baseball was played in the major leagues during World War II without pretending to imply that it was the same without PEE WEE, THE YANKEE CLIPPER, RAPID ROBERT and THE KID.