When Harry Met the Bronx Bombers: The History of the Yankee Stadium Concessions

This article was written by Don Jensen

This article was published in Yankee Stadium 1923-2008: America’s First Modern Ballpark

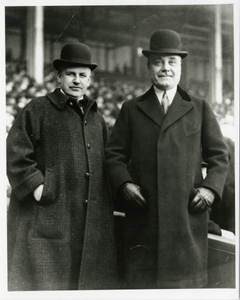

Harry M. Stevens, shown at left with Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert, was the Yankees’ official concessionaire through the 1963 season. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

The 12-page official program of the new “Greater New York Base Ball Club of the American League“ at its home opener on April 30, 1903, was published by Harry M. Stevens, who had built a concessions empire since the 1880s that extended from the Midwest to New England. Stevens had made a fortune in New York City the previous decade managing the concessions at the Polo Grounds, home of the National League Giants, the new club’s now immediate rival; Madison Square Garden; and the upstate Saratoga Racecourse. The association of Stevens’ firm with the new American League franchise (at first called the Highlanders) would enable Harry to become a key force in the emergence of the franchise as a dynasty in major-league baseball.1

The advertisements scattered throughout the inaugural program and scorecard, priced at 5 cents, reflected the goal of concessionaires everywhere: to enhance and profit from the fan experience at the ballpark. In addition to player rosters and space to keep score, the card included advertisements for Philip Morris cigarettes, Dewar’s scotch, Coca-Cola, Horton’s ice cream cones, Atlas motor oil and grease, Pommery champagne, and Henry Rahe’s Café across the street. At Rahe’s, fans could order Jac. Ruppert’s Extra Pale, Knickerbocker, and Ruppiner beers. One ad tried another way to pique fan interest: “Any baseball player who will hit the ‘Bull Durham’ cut-out sign on the field with a fairly batted ball during a regularly scheduled league game will receive $50.00 in cash [almost $1,700 in 2022].”2

THE BUSINESS OF CONCESSIONS

But profits for the new franchise from selling scorecards and advertisements alone would be small. By contrast, catering to the fans’ desire for refreshments during the game would provide the Highlanders’ owners, gambler Frank Farrell and former New York City Police Chief Bill Devery, with a vital source of revenue to supplement income from ticket sales. In selling concession rights to an experienced and shrewd entrepreneur like Stevens, the club could avoid the burden of procuring food and beverages, hiring cooks, vendors, and other salespeople, setting prices, and meeting fans’ expectations for superior quality. (Some clubs at the time, such as the Chicago Cubs, sold concessions themselves.)

When the Highlanders opened for business at American League Park – soon after called the Hilltop due to its location on a ridge in northern Manhattan – the question of what food and drink to sell at ballparks already had a long and controversial history. Initially, baseball owners were slow to provide concessions and other entertainment to fans. However, unauthorized bars, liquor booths, rum shops, and “restaurants” – saloons – often popped up near ballparks and siphoned off potential revenue from the teams. Gradually, clubs came to offer items such as cherry pie, cheese, chewing tobacco, tripe, chocolate, and onions, like food sold at fairs, racetracks, circuses, railway stops, and other outdoor venues. In the 1880s, Chris Von der Ahe, a German immigrant and later Stevens’ mentor, bought a team, the St. Louis Browns of the American Association, to increase profits at his bar near Sportsman’s Park, the Browns’ home. He later added an amusement park with a Bavarian-style beer garden, a water flume ride, an artificial lake, and a racetrack near the outfield. The American Association, known as the “Beer and Whiskey League,” prohibited gambling on its grounds and disapproved of the racetrack but permitted beer sales. In contrast, teams in the more established National League sought a more respectable clientele by having higher ticket prices and forbidding the sale of liquor at games.

The controversy over alcohol in ballparks raged well into the twentieth century when the growing temperance movement lobbied baseball clubs to eliminate bars and hard liquor, and to sell beer more discreetly. (Soft drink manufacturers marked their beverages as “temperance drinks” – often soda water sweetened with syrup.) However, it was impossible for the New York American League club to fully board the Prohibition bandwagon after Jacob Ruppert, who inherited a fortune in the family brewing business, purchased the team on January 11, 1915.

Harry M. Stevens set up shop at the Hilltop with a proven business model that improved on Von der Ahe’s approach. Unlike Von der Ahe, Stevens put the fan experience of watching the game above everything else. Stevens may have been the first concessionaire to have his vendors patrol the stands during the games. He placed drinking straws in glass soft-drink bottles so spectators could watch the play as they sipped, and varied product offerings by the city to accommodate local tastes. Eventually, Stevens controlled so many venues that several items on his menu became standard ballpark fare, including peanuts, nonalcoholic beverages, and ice cream.

Later baseball legend credited Stevens with introducing hot dogs to ballparks, but there is no evidence that in 1903 he offered frankfurters on his menus, either at the Hilltop or elsewhere. Hot dogs, initially working-class street food, were first introduced to the United States by German immigrants who settled in the Midwest after the Civil War. Around 1867, Charles Feltman, a German-American restaurateur, began selling sausages in rolls at Coney Island. In the 1880s Von der Ahe introduced a “wiener wurst” in St. Louis, where they became a staple at Browns games. The food also may have grown in popularity in New York City with the arrival of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe in the early 1900s.

There is no information on the profits Farrell, Devery, and Stevens made from concessions sales in the early years at the Hilltop. However, circumstantial evidence from major-league clubs elsewhere suggests they were substantial. One team reported making more than $2,000 in 1908. Another earned an estimated $1,000 on Coca-Cola sales, with a cut of 40 cents on a case of 24 bottles selling at a nickel apiece. By 1910, Stevens had a son at Yale, rode around in a “swell” automobile, sat in a box at the theater, smoked dollar cigars, dined at swanky Sherry’s restaurant, and lived in a series of fancy Midtown hotels.3

The best indicator that business was good was Harry Stevens’ steady rise as a central player in the business affairs of the Highlanders and other clubs. With the money rolling in, Stevens became a dependable financier to whom owners could turn if they needed to meet a payroll or just the money to paint an outfield fence. Even as he developed his business with the Highlanders, he served on the New York Giants board of directors, with whom he had long been identified. Stevens considered becoming a partner with Brooklyn owner Charles Ebbets in 1908 and an owner of the Giants after the death of John T. Brush in 1912. Thus, when Jacob Ruppert and businessman Tillinghast L’Hommedieu Huston bought the New York American League team in 1915, the new owners awarded Stevens the concessions rights, no doubt partly due to his large bankroll.

HIGHLANDERS TO YANKEES

Stevens’ position with the Yankees was bolstered after the 1920 season, when Ruppert and Huston hired Ed Barrow, Harry’s longtime friend and former business partner, from the Boston Red Sox to become the business manager of the Yankees. Barrow had spent a lifetime in baseball as a minor-league manager, minor-league owner, minor-league president, and major-league manager. Before he joined the Yankees, Barrow had never won a pennant as a general manager. But with Ruppert’s support, Barrow created one of the greatest dynasties in sports history. In his 24 years with the club, the Yankees won 14 American League championships and 10 World Series.4

Barrow and Stevens had been friends since the 1890s, when both men frequented the Pittsburgh sports scene. Barrow landed a job in a hotel that catered to sportsmen. Barrow and Stevens were partners, hawking scorecards, refreshments at the ballpark, and playbills to local theaters.5 The partnership soon broke up amicably after Barrow decided to remain in baseball and not accompany Stevens to New York City to sell food and drink for the Giants. But they remained close.

Stevens came to hate Huston, who wanted to break the concessions contract with the Stevens family and install his son as the concessionaire at the Polo Grounds, which the Yankees shared with the New York Giants. Meanwhile, Barrow was caught in the middle of the squabbling between Huston and Ruppert over how to run the team, especially Huston’s criticism of Miller Huggins’ effectiveness as on-field manager. Huston in any case wanted out, and after negotiations for the sale of the club to a third party fell through, he tried to find a purchaser for his half of the team. Ruppert did not want a new partner, so he bought out Huston himself. After completing the transaction, Ruppert offered Barrow the chance to buy 10 percent of the Yankees for $300,000. Barrow borrowed the money from Harry Stevens, intending to repay the loan with future dividends. Ruppert promoted Barrow to team treasurer and gave him a spot on the Yankees’ board of directors. Stevens’ contract with the Yankees was secure.

At this point in his career, Stevens styled himself as “publisher and caterer … from the Hudson to the Rio Grande” – the latter a reference to his racetrack in Juarez. With the opening of Yankee Stadium on April 18, 1923, the financial heart of Stevens’ far-flung concessions empire shifted from the Polo Grounds across the river to the Bronx. The new facility was the largest in baseball and could accommodate about 60,000 hungry customers. (At the height of the Yankees’ popularity in the 1920s and 1930s, about 80,000 fans could be squeezed in.) This size was not daunting to Stevens, who was used to overseeing large crowds. (He catered the famous Dempsey-Carpentier heavyweight championship bout – an early “Fight of the Century” – in Jersey City in 1921, where almost 90,000 people attended.) It was said of his firm that it served up to 250,000 spectators at various ballparks and racetracks on summer afternoons. As Stevens’ ties to the Yankees grew, Harry and his sons – especially Frank – became close friends with national idol Babe Ruth, who conspicuously consumed Stevens’ frankfurters. Ruth gave the elder Stevens a signed picture of himself that read, “To my second dad, Harry M. Stevens.” After he hit 60 home runs in 1927, Ruth presented Harry with a poster showing an image of every ball he hit out of the park. Each had the date of a blast, and they were numbered from 1 to 60.

Concession salesmen worked exclusively on commission, and sales were often dependent on the weather. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

THE BUSINESS OF CONCESSIONS

Concessions provided an important part of the Yankees’ profits throughout the following years. In the 1929 season, the last before the great stock-market crash, about one-third of the team’s net income – $271,028 – came from selling food and drink. This was higher than the crosstown Giants (whose concessions were still managed by the Stevens company) and the second highest in the major leagues.6 During the Depression in 1933, the Yankees made $59,000 from concessions sales even though the team lost money overall.

In May 1934 Harry Stevens, 76 years old, died of pneumonia. Two of Harry’s sons, Frank and Joe, who informally ran the company in their father’s final years, formally took over. After that, business at Yankee Stadium remained profitable for the company and the club.7 In the 1940s the Stevens empire operated not only in Yankee Stadium and at the Polo Grounds but at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, Braves Field and Fenway Park in Boston, and high-profile racetracks like Churchill Downs, Pimlico, Belmont Park, Saratoga, Hialeah, and Narragansett. Stevens’ venues also included minor-league parks, dog tracks, state fairgrounds, and polo fields. Other concessions networks operated around the country, most notably that of the Jacobs brothers, Sportservice, Inc., which had its headquarters in Buffalo and operated in venues not served by Harry M. Stevens. Several smaller, profitable chains prospered on the West Coast. But while concessions firms came and went, the Stevens empire seemed eternal, like Yankee Stadium itself.8

However, profit margins in the industry remained small. In 1942 a representative of Sportservice provided a cost itemization for each dime hot dog his company sold and from which his firm earned only half a cent.9 Horse racing crowds had the highest average – one reason Harry Stevens controlled prestigious tracks around the country. Fans of track and field spent about 40 cents per capita. Baseball crowds spent 15 cents (22 cents at doubleheaders), and boxing and hockey crowds spent 8 cents. Football fans paid on average 10 cents in mild weather and 25 cents in bad weather. (They were not generally crowds who spent a lot of money, since they sat on their hands during a game and were unwilling to reach into their bulky overcoats for a dime.) Football fans spent more when it was cold: They clamored for hot food, paper rain hats, and unlimited coffee.10

Profits also depended on less predictable factors like fan moods and the weather. Experienced salespeople, who during the Great Depression were frequently older men, varied their sales pitch based on their assessment of crowd psychology. They worked exclusively on commission, getting from 10 to 20 percent of total sales. One veteran salesman at Yankee Stadium, who had refined his sales pitch, claimed he made $26 on a good day but only $3 on his worst. One of his less experienced colleagues usually pulled in $2 to $8. Sudden weather changes could be disastrous. Counting on a sweltering day, a concessionaire might prepare to sell copious quantities of ice cream and cold drinks only to find that unexpectedly cold weather might shift the demand to coffee, hot dogs, and soup.11

Managing an army of vendors at a facility as large as Yankee Stadium was complicated. Forgetting the company founder’s belief in the importance of audience preferences, Stevens company executives came to produce concessions the way Henry Ford manufactured autos: They strictly rationed supplies and insisted on the uniformity of practices – coffee was made the same way every game, and vendors were trained how to put a hot dog in a roll and apply mustard with a minimum of motion. They kept track of coffee sales by counting the number of paper cups issued. Still, there were many opportunities for vendors to cheat. Most bags of peanuts contained 50 to 60 items, but a vendor could pick up empty bags around the ballpark and reapportion his stock to make it look as though he sold more. Harry Stevens did not make his employees sew up their pockets, as did the Jacobs brothers, but the firm carefully monitored the activities of all his employees. It required all vendors to wear the prices of their wares on a printed card in their hat so they could not overcharge customers.12

DECLINE

The Yankees opened the 1964 season without Harry M. Stevens as their concessionaire.13 The team had replaced Stevens with National Concessions Service, a division of Automatic Canteen Company, a firm partly owned by the team’s owners, businessmen Del Webb and Dan Topping. The menu now included novel items such as shrimp rolls, pizza, fish sandwiches, and milkshakes.14

Having the Yankee owners control the team and the Stadium’s food and drink operation made good financial sense for the team. In any case, the formidable grip of the Stevens operation on the industry had long been weakening. The Stevens family continued to be reluctant to adapt to evolving audience tastes. (The Stevens company was the only major concessionaire to boil rather than fry its hot dogs, because the elder Harry insisted on cooking them that way.)15 The reluctance to innovate was reinforced by the large scale of the Stevens holdings, which forced management to standardize its offerings with little variation “from the Hudson to the Rio Grande.”16 Finally, a company like Stevens, with a highly variable level of concessions profits as its core business, almost inevitably would have less resilience than a larger food conglomerate for which concessions were only a sidelight.17

At Yankee Stadium, Automatic Canteen, under various names, managed concessions until the Stadium closed in 2008.18 The Yankees then created a new firm in partnership with the Dallas Cowboys called Legends Hospitality.19 That conglomerate focused on food, beverage, merchandise, retail, stadium operations, and entertainment venues like the San Francisco 49ers’ Levi’s Stadium and the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Legends tentacles also stretched beyond food to helping teams operate stadiums and selling naming rights and personal seat licenses.

Harry M. Stevens could not have dreamed of culinary offerings at the new Yankee Stadium today. They include meatball parmesan sandwiches, egg creams, cheesesteaks, garlic fries, and Buffalo chicken quesadillas, along with Nathan’s hot dogs. Nor could he have conceived of the video menu boards scattered throughout the ballpark. But he would be on more familiar ground reading the results of a Yankee Stadium concessions case study conducted by Legends in 2014. The report found that the most effective way of increasing concessions sales per capita was to increase the average number of dollars customers spend per transaction.20 This was sound business practice, indeed, and one Harry Stevens pioneered more than a century ago.

DON JENSEN is a longtime member of the Society for American Baseball Research and has written or co-authored many books and articles on the sport. He was the 2015 winner of the Chairman’s Award of the SABR Nineteenth Century Committee. From 2018 to 2021 Jensen was editor of the award-winning annual book series Baseball: New Research on the Early Game (McFarland). He is currently editor of The Inside Game, the newsletter of the SABR Deadball Era Research Committee, and a member of the selection committee for SABR’s Larry Ritter Book Award, which recognizes the best new baseball book primarily set in the Deadball Era that was published during the previous calendar year.

NOTES

1 By 1911 the more headline-friendly “Yanks” or “Yankees” had largely supplanted “Highlanders” as the unofficial nickname of the American League Base Ball Club of Greater New York. But in the writer’s view, a certain clarity is achieved by using “Highlanders” for the club during its tenure at Hilltop Park (1903-1912) and reserving “Yankees” for thereafter.

2 Marty Appel, Pinstripe Empire: The New York Yankees From Before The Babe to After The Boss (New York: Bloomsbury, 2012), 20-21.

3 David Quentin Voigt, The League that Failed (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press; Illustrated edition (June 1, 1998), 69.

4 Daniel R. Levitt, “The Making of Ed Barrow.” Base Ball, vol. 1, No. 2, (Fall 2007): 67.

5 Levitt, 68.

6 The Chicago Cubs claimed $132,162 in net concessions in 1929, the highest in the major leagues.

7 After Stevens’ wife, Mary, died in 1941, Harry’s estate was valued at $1.2 million. https://vindyarchives.com/news/2013/apr/21/valley-relishes-harry-stevens/. Accessed November 21, 2022.

8 Howard Whitman, “Selling the Crowds,” Saturday Evening Post, April 11, 1942: 25. Some independent firms worked on a single venue or with one partner only. Fred Kanen supplied $400,000 worth of food, drink, and programs to 2 million fans each year at Madison Square Garden. The Miller brothers, Frank, and Paul, had a “single plum,” the Ringling circus, for which they Millers supplied 6 million fans and the Ringling’s elephants.

9 The breakdown probably was similar for the frankfurters sold by the Stevens company at Yankee Stadium: meat, 3 cents; roll, 1 cent; vendor’s commission, 1½ cent; cost of concession rights, 2½ cents; wastage ¾ cent; and overhead, ¾ cent. There was twice as much profit to be had by selling soft drinks: wholesale price per bottle: 3⅓ cents; breakage and handling costs: ¼ cent; ice: ½ cent; vendors commission: 1½ cents; costs of concessions rights: 2½ cents; overhead: ¾ cent; paper cup: ⅙ cent. These costs totaled 9 cents, leaving a penny profit. Whitman, 62.

10 Whitman, 62.

11 Whitman, 25.

12 Whitman, 25.

13 Appel, 350.

14 Appel, 350.

15 When Bob Lurie purchased the San Francisco in1976, he wanted to introduce wine, but the Stevens Company was aghast, since it went against traditional ballpark fare.

16 That problem popped up in San Francisco as well in 1958 when the Stevens operation set up shop after the Giants move. Some local fans not only were reluctant to embrace their new club, but preferred the concessions their beloved, now-defunct Seals sold for decades.

17 Stevens took a major hit in the 1980s, when many cities forbade beer sales, a major moneymaker, before the end of the game.

18 Aramark acquired the Harry M. Stevens name in 1994.

19 Appel, 350.

20 Yankee Stadium Concessions Case Study: https://www.legends.net/hospitality/yankee-stadium-concessions-case-study#:~:text=Yankee%20Stadium%20Concessions%20Case%20Study%20CONCESSIONS%20GROWTH%20AT,growth%20for%20its%20stands%20without%20raising%20food%20prices. Accessed November 21, 2022.