Whitey Witt: The First Yankee Hitter to Come to the Plate at Yankee Stadium

This article was written by Mike Richard

This article was published in Yankee Stadium 1923-2008: America’s First Modern Ballpark

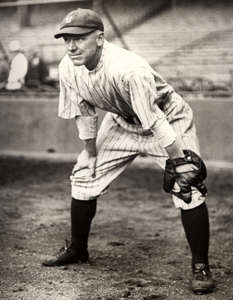

Whitey Witt batted .301 as a Yankee, from 1922-1925. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

It was long before the days when the elegant voice of Bob Sheppard introduced the starting lineup at Yankee Stadium.

However, if there was a public-address announcer at the Bronx ballpark on the day it opened on April 18, 1923, before a baseball record 74,200 fans – and there wasn’t – it may have sounded something like this …1

“… Leading off for the New York Yankees, the center fielder, Whitey Witt.”

Witt was born Ladislaw Waldemar Wittkowski on September 28, 1895, in Orange, Massachusetts, and grew up in the nearby town of Winchendon.

But old-time baseball fans will remember him as Whitey Witt. He shared the outfield with Babe Ruth and Long Bob Meusel, playing that opening season for manager Miller Huggins.

“I made the major leagues because I could hit, I could field and I could run,” Witt recalled in a 1985 interview, three years before his death. “That was my biggest asset there.” The .287 lifetime hitter had three seasons batting over .300.2

The pregame festivities featured Governor Alfred E. Smith throwing out the first pitch, while fans arriving early to the game were serenaded by John Philip Sousa’s Seventh Regiment Band.

Starting pitchers for the Stadium’s inaugural game were Bob Shawkey for the Yankees and Howard Ehmke for the Boston Red Sox.

History notes that shortstop Chick Fewster of the visiting Red Sox was actually the first batter in Yankee Stadium history. However, in the bottom of the first, Witt led off for the Yankees and grounded hard to Fewster, who threw to George Burns at first for the out.

In the second inning, Red Sox first baseman Burns would earn the first hit in the history of the ballpark. However, when he also attempted to get the first stolen base, Burns was thrown out by catcher Wally Schang.

In the third inning, second baseman Aaron Ward had the first Yankees hit at Yankee Stadium, and after the game both he and Burns each received a box of cigars for their historic hits.3

Ruth hit the first home run at the Stadium, a three-run shot to right field in the third inning to help defeat his former team, the Boston Red Sox, 4-1. Witt was on base, having worked a walk. In the bottom of the fifth, Witt himself had a single to right-center.

“It was an amazing day,” Witt recalled in a 1984 interview with Rich Westcott. “The new ballpark, the crowd, all the excitement. It was an experience that you could never repeat in a hundred years. We were in awe when we first saw the park. It seemed so big. Huge. At the time, there was nothing like it in baseball. Looking around, it was enough to make your eyes pop out.”4

Witt began his career in 1916 playing five years with Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics.

It was while playing for Mack that his lengthy name was shortened.

“Mack didn’t want to write Wittkowski on the batting card every day, so he changed my name to Witt,” he told Westcott. “Then, because I had blond hair, he called me Whitey.”

Witt got what he called “the biggest break of my life” when he was sold to the pennant-winning New York Yankees on April 17, 1922.5

After the Yankees had won their first pennant the previous year, outfielders Babe Ruth and Bob Meusel ignored Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis’s ban on barnstorming, which was a popular postseason sidelight in those days. Landis slapped each player with a six-week suspension, which kept them out of the Yankees lineup until May 20, 1922, and the Yankees had to find some outfielders to pick up the slack.

When the suspended duo returned, Witt found himself in center field to comprise the outfield of Ruth in left and Meusel in right. At the time, the Yankees played their home games at the Polo Grounds when the New York Giants were on the road.

“Babe and I got along great because both of us drank,” Witt said with a laugh in our 1985 interview. “The rest of the players used to call me his errand boy because when we’d get on the road and he wanted a bottle of whiskey, he’d say, ‘Whitey, here’s $20, go down to the desk’ … ’course this was during prohibition … ‘Go down to the desk and get me a bottle of whiskey.’ Then we’d go up in his room and raise hell,” Witt said.6

During one of their drinking sprees, an undercover detective learned of their carousing and blew the whistle on the ballplayers. Since Ruth was the big name, he was fined $5,000 while Witt was hit with a $500 fine.7

There was also an incident five days after The Babe returned from his barnstorming suspension in late May 1922: A fan began needling Ruth from the stands, and The Babe went after him. While the fan fled, it took several police and teammates to restrain Ruth.8

“Shortly after the incident in which Babe tried to get into the stands, (Giants owner) Charles Stoneham informed our owners that he wanted the Yankees out of the Polo Grounds,” Witt said. “They didn’t know that the Yankees already owned property within sight of the Polo Grounds and even before Stoneham realized it, the Yanks were starting to build.”9

The Yankees swept all four games during that inaugural series against the Red Sox.

“I was a punch hitter and a good bunter,” Witt told a reporter from his hometown newspaper, the Winchendon Courier. “I used to get 40 hits a year on bunts. Nowadays it seems the art of bunting is lost. Everybody is swinging for the fences.”10

During that 1923 season, Witt helped the Yankees defeat the St. Louis Browns for the pennant, snapping back after being beaned by a bottle thrown from the stands into center field at the beginning of a crucial series with the Browns.

According to a story by Tim Quinn in Today’s Sunbeam in 1983, Witt was going back on a ball in deep center field at Sportsman’s Park when a bottle came out of the stands, hitting him in the head and knocking him out.

American League President Ban Johnson offered a reward for the information leading to the conviction of the bottle thrower.

“A popular account of the incident said a 10-year-old boy threw the bottle. The reward however, was finally awarded to a spectator who persisted in his claim that the bottle had been on the field already and Witt kicked it up into his face while giving chase to the fly ball,” Quinn wrote.11

Quinn wrote that information – perhaps fabricated – emerged that Witt “was not struck by a thrown bottle, but rather the bottle had been thrown onto the field earlier and Witt unknowingly stepped on it. While in pursuit of the fly ball, the bottle bounded up and struck him above the eye.”12

Regardless, the incident provided the Yankees with more inspiration to beat the Browns in 15 of the 20 games the two teams played during New York’s pennant-winning season.

Witt came back in the series with several timely hits, drove in two runs – including the pennant clincher – and chased a long fly into deep center, making a dramatic leap into the stands to record the out. The St. Louis fans, apparently contrite after what had happened to him earlier in the series, gave him a tumultuous ovation.13

The Yankees center fielder also enjoyed his best offensive season in Yankee Stadium’s first year with a .314 batting average and career highs in home runs (6), runs batted in (55), and runs scored (113). His .979 fielding average led American League outfielders.

In the 1923 World Series, Witt went 6-for-25 with two doubles and four RBIs. A year later, he batted .297 for the second-place Yankees, but his future with the team appeared on the wane.

Hitting just .200 as a backup outfielder, Witt was released in July 1925.

After baseball, Witt and his wife, Mary (McClain) Witt, owned a farm in Alloway Township, New Jersey. He also operated a tavern called Whitey’s Irish Bar in nearby Salem, New Jersey, for some 17 years.

Witt was invited back to Yankee Stadium 14 times for annual OldTimers games, introduced as the first Yankee to come to bat at the Stadium.14 Witt attended the 25th and 50th anniversaries of Yankee Stadium, and in 1973 he cut a cake at home plate with Ruth’s widow to commemorate the golden anniversary of the ballpark.15

In his old age, despite his longtime absence from the game, Witt said he still received four or five fan letters per week, as well as baseball cards to autograph for young fans.16 That lasted until his death at the age of 92 on July 14, 1988.

MIKE RICHARD is a lifelong Red Sox fan, a retired guidance counselor at Gardner (Massachusetts) High School and a longtime sports columnist. He has written for the Gardner News, Worcester Telegram & Gazette, and Cape Cod Times. A Massachusetts high-school sports historian, he has authored two high-school football books: Glory to Gardner: 100 Years of Football in the Chair City and Super Saturdays: The Complete History of the Massachusetts High School Super Bowl. He has also documented the playoff history (sectional and state championships) of all high-school sports in Massachusetts. He lives in Sandwich on Cape Cod with his wife, Peggy, and is the official historian of the Cape Cod Baseball League. They are the parents of a son, Casey, and a daughter, Lindsey, and have two grandchildren, Theo and Grace.

SOURCES

In addition to the sources shown in the notes, the author used baseball-reference.com, SABR.org, Newspapers.com, and www.retrosheet.org. for background information, and the following:

Schott, Arthur O. “The First Game at Yankee Stadium,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, 1973.

Webb, Melville E., Jr. “Ruth’s Homer Beats Sox Before 74,200,” Boston Globe, April 19, 1923: 1.

NOTES

1 According to Frederick C. Bush’s article “Babe Ruth Homers in Yankee Stadium’s Grand Opening, Hinting at Franchise’s Dynastic Future” for SABR’s Games Project, the attendance for the day was exaggerated. Bush cited Robert Weintraub’s comment that Yankees business manager Ed Barrow admitted he had added standing-room fans to his original estimate and amended his Opening Day figure to 62,200. Weintraub wrote that even this figure is “probably still exaggerated, but [it was] nevertheless by far the largest crowd in the sport’s history.” Robert Weintraub, The House That Ruth Built: A New Stadium, the First Yankees Championship, and the Redemption of 1923 (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2011), 17-18,

2 Author interview with Witt, July 1985. Hereafter cited as Witt interview.

3 Ed Cunningham, “Echoes from That Babe Ruth Swat,” Boston Herald, April 19, 1923: 14.

4 Rich Westcott, “Whitey Witt,” SABR BioProject. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/whitey-witt/.

5 Witt interview.

6 Witt interview.

7 Jim Ogle, “The First Yankee to Bat at Yankee Stadium Returns,” Yankees Magazine, August 1983: 15.

8 Ogle.

9 Tom Quinn, “Salem County’s Major Leaguer: In Baseball’s Golden Age, Whitey Witt Played Alongside the Greatest,” Today’s Sunbeam (Salem, New Jersey), 1983 (exact date unknown). While Witt said this incident happened in May of 1922, his dates were probably off since Yankee Stadium was likely already under construction by that time.

10 “Whitey Pays Visit to His Family Here,” Winchendon (Massachusetts) Courier. December 30, 1970.

11 Quinn.

12 Quinn.

13 Quinn.

14 Quinn.

15 Quinn.

16 Witt interview.