Who Had the Best Final Season?

This article was written by Paul White

This article was published in Sandy Koufax book essays (2024)

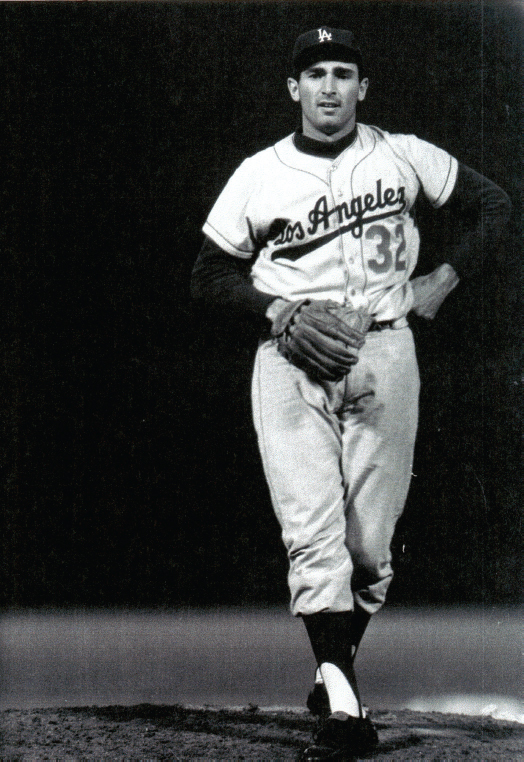

Sandy Koufax posted a career-low 1.73 ERA and struck out 317 batters in his final season with the Dodgers in 1966. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

The fact that Sandy Koufax had arthritis in his left elbow was well known for the final two years of his career. He woke up after a spring-training game in 1965 unable to straighten his pitching arm and was flown back to Los Angeles for testing. Koufax made no secret of the fact that he’d been diagnosed with “traumatic arthritis.” It was reported in the Los Angeles Times as early as April 4 of that year1 and was mentioned later that year in the broadly syndicated columns of Jim Murray2 and Dick Young.3

In short, everyone knew about it for two years before Koufax announced his retirement. So why, in November of the following year, was the news of his retirement reported as a “bombshell”4 that left people “stunned?”5

The answer likely lies in the fact that he was still pitching better than anybody in baseball. As Jane Leavy said in her wonderful biography of Koufax, “No, what was disconcerting, revolutionary even, was the idea. Athletes don’t quit, certainly not after their best season. They don’t walk away. They limp away.”6

Leavy may have overstated her case a bit, because 1966 likely wasn’t Koufax’s best year. According to Fangraphs WAR, it was his third best, behind 1965 and 1963. According to WAR on Baseball-Reference.com, it was his second best, behind 1963. According to traditional statistics, Koufax did, by the barest of margins, win the most games and have the lowest ERA of his career in 1966, but he also had his worst winning percentage and fewest shutouts since 1962, and his lowest strikeout rate since the Dodgers’ first season in Los Angeles, 1958.

Yet Leavy’s main point is valid. Koufax was still pitching brilliantly, easily the best pitcher in baseball yet again. He won his third Cy Young Award, and, like the first two, the vote was unanimous. He did not just have a great final season but went out with five successive seasons as the ERA leader, something no other retiree can claim. In addition, he led the league in innings pitched his final two seasons.

Since 1966 proved to be his final season, the question has long been asked if it’s the finest final season anyone has ever had.

As with most things in life, the answer is: “It depends.”

What it depends upon lies in how we choose to define our terms. For instance, are we only talking about baseball players? Because, if we’re not, then Koufax may not even have had the best final season among athletes whose final game was played in 1966. Jim Brown’s final season with the Cleveland Browns was 1965 (his final game was played on January 2, 1966), and all he did was lead the NFL in rushing, total yards, and touchdowns while winning his fourth league MVP award.

Because it’s virtually impossible to compare a baseball season to a football season, it makes sense to limit the discussion to just the one sport that Koufax played.

That still leaves us with a few terms to define. Do we mean a player’s final full season, excluding any part-time years that may have finished his career? If so, it might be hard to surpass someone like Dick McBride of the 1875 Philadelphia Athletics, who won 44 games that season, his final full year in baseball. He pitched in just four games the next year before calling it quits.

That situation seems to be outside the spirit of the exercise though, doesn’t it? Koufax walked away after 1966. He didn’t come back, pitch four ineffective games in 1967, and then retire. So let’s stick with the same standard when comparing him to others.

Speaking of Dick McBride, and other players from baseball’s earliest days, what about timeframe? When we say best final season “ever,” do we mean in the full statistically recorded history of baseball, all the way back to the nineteenth century, when pitchers were routinely posting preposterous innings-pitched totals, it took six balls to walk a batter, the fielders had no gloves, and batters were out if a foul ball was caught on a bounce?

If we choose to go back that far, it seems impossible for Koufax’s final season to be considered superior to Jim Devlin’s. As the only pitcher on the roster of the Louisville Grays of the National League in 1877, Devlin threw 559 innings, started and completed all 61 games the team played, won 35 of them, led the league in ERA+, and had a WAR total of 13.2, a mark that has been surpassed in a single season only by Babe Ruth, Walter Johnson, and a few other nineteenth-century pitchers.

That was Devlin’s final year as a player because, after the season ended, he confessed to purposely losing games and was banned for life. Still, a final season is a final season, and Devlin’s numbers would put him well beyond Koufax in 1966. It’s hard for any modern pitcher, even a workhorse like Koufax, to compete with the numbers that can be compiled by the only pitcher on a decent team’s roster.

In keeping with the spirit of our other definitions, and the attempt to compare apples to apples (or baseballs to baseballs) on as level a playing field as possible, it seems that nineteenth-century pitchers played under such different circumstances than Koufax that they shouldn’t be included in the discussion.

There’s another tricky situation to address. Many Negro League players continued their playing careers in leagues that still aren’t considered major league. That means some of them had their final official “major league” season when they were in the prime middle years of their careers. Should we be considering those as “final” seasons?

For instance, Charlie “Chino” Smith had a remarkable year in 1929 for the New York Lincoln Giants of the American Negro League. The 28-year-old Smith was in his prime, entering that season with a career major-league batting average of .379. Playing in 66 of the Giants’ 68 league games, he led the league with 86 runs scored, 29 doubles, 22 homers, and a batting line of .451/.551/.870. His 1.421 OPS is nearly identical to Barry Bonds’ mark in 2004. His WAR total of 5.9 extrapolated to a 162-game season would stand at 14.1, the exact mark Babe Ruth posted in 1923, his only MVP season. It’s one of the most spectacular seasons in major-league history, and it’s the final major-league season Smith played.

So does that count as one of the great final seasons? We could count it, but the problem is that Smith did nothing to stop playing major-league baseball. In fact, at the time, he wasn’t even aware that he was playing “major league” baseball, because the American and National Leagues were the only ones considered “major” at that time by both “organized baseball” and the public in general. Only in 2020 was the American Negro League finally categorized as “major.”

Smith kept right on playing when the ANL dissolved after that season, and still for the New York Lincoln Giants. He batted .417 in 1930 and led the Giants to a 37-13 record and a place in a postseason series against the Homestead Grays. In the finale of that series, Smith was injured in a collision with Walter “Rev” Cannady, effectively ending his career.7 He died in January 1932 at the age of just 30, and for years it was believed that Smith’s injury and a case of yellow fever contracted while playing in Cuba led to his death, but more recent research points to cancer of the stomach and pancreas as the cause.8

It would be very hard to claim that Koufax’s final season in 1966 was better than Smith’s season of 1929, but Smith’s year was “final” only by technicality. He wasn’t retired or injured or banned or even demoted. His team continued as before, just outside the league structure that allows it to be viewed as a major-league team. He continued to play top-caliber baseball past 1929, so this, too, is a type of season that seems to fall outside the point of the discussion.

That leaves us with a field of prospects consisting of baseball players from 1900 forward who were playing in their final season on the field at any level. We still must decide one more term, and that is “finest.” When we say a player’s final season was the “finest,” are we speaking of the finest quantitative performance, i.e., he posted the best statistics, or the most recognized performance, i.e., he received the most accolades?

Looking at just one likely doesn’t provide a full picture of the season. There have been wonderful statistical seasons that went virtually unrecognized at the time, (John Valentin in 1995, for example9), just as there have been seasons rewarded with various honors that likely didn’t deserve them (such as Pete Vuckovich in 1982).10 To get the clearest possible picture of the quality of the season in historical context, and in the context of how it was viewed at the time, we need to look at both.

First, the statistics.

Since 1900, only five pitchers have won at least 20 games in their final season: Koufax, 27 in 1966; Lefty Williams, 22 in 1920; Henry Schmidt, 22 in 1903; Eddie Cicotte, 21 in 1920; and Mike Mussina, 20 in 2008. Clearly, Koufax has a big advantage here, even before noting that two of his competitors, Williams and Cicotte, should lose a few accolade points since they were banned by baseball for throwing the 1919 World Series. Of these five, Koufax also had the lowest ERA, started the most games, completed the most games, and had the most strikeouts, best ERA+, and highest WAR.

Pitcher wins are somewhat out of vogue now and are certainly harder to come by given modern pitcher usage, so let’s shift to ERA, and more particularly ERA+ since that accounts for the differences between ballparks and run-scoring eras. Searching for pitchers in their final major-league season who threw at least 100 innings, had an ERA of 2.50 or better, and an ERA+ of 150 or better, we find just 10 men besides Koufax. Six of them–Max Manning, Bill Byrd, Leon Day, Amos Watson, Roy Welmaker, and Dick Matthews–pitched in the Negro Leagues and all but Matthews pitched after their “final” major-league season, either in Black leagues not currently considered major, Mexican baseball, or the minor leagues. There is no known record of Matthews pitching again, but his 2.17 ERA and 161 ERA+ don’t approach Koufax’s marks of 1.73 and 190, respectively, and didn’t lead his league as Koufax did.

Of the four remaining pitchers–Larry French, J.R. Richard, Ned Garvin, and John Tudor–French’s 180 ERA+ in 1942 came the closest to Koufax, but he did it in almost 200 fewer innings. Ned Garvin’s 1.72 ERA in 1904 was a point better than Koufax’s mark, but in 130 fewer innings and in a much lower run-scoring environment as indicated by his much lower ERA+ of 159. None of the 10 men led their respective leagues in either ERA or ERA+ as Koufax did.

Let’s move on to strikeouts. Koufax fanned 317 hitters in 1966, leading the National League. The next closest pitcher was José Fernández, who had 253 strikeouts in 2016 before tragically dying in a boating accident at the end of that season. No other pitcher surpassed even 200 strikeouts in his final season, and the only pitchers to lead their league in strikeouts in their final season, as Koufax did, were Leon Day in 1946, and Jim LaMarque in 1948, and both continued their careers elsewhere after those seasons.

Shifting to WAR from baseball-reference.com, we find no pitcher anywhere near Koufax’s mark of 10.3 in his final season. The closest was José Leblanc in 1921, when he had 6.2 WAR to lead the Negro National League, but he pitched after that season in Cuba. Other pitchers also led their respective leagues in WAR, but they were all Negro Leagues pitchers, too, and all played somewhere after their final “major league” season, except for the aforementioned Dick Matthews, whose 3.8 WAR in the Negro Southern League, for a team that played just 48 league games, would extrapolate to 12.8 WAR over a 162-game season, so we shouldn’t simply ignore it. On the other hand, it’s a record posted by a pitcher who was never heard from again, playing in a league that existed for just one season, and we must project performance to put him in the same class as Koufax. It seems safe to go ahead and pass him over as a candidate.

Moving along to accolades, this is a pretty short discussion when it comes to pitchers. There have been 124 Cy Young Awards handed out through the 2022 season. Just one of those was given to a pitcher who was playing his final season–Koufax in 1966. ’Nuff said.

It’s clear that no pitcher in the modern era had a final season as good as Koufax had. If we’re going to find a player to challenge him, it will have to be a position player. We’ll examine the Triple Crown statistics first.

Just eight players have hit as many home runs in their final season as Koufax had wins, 27. The most was 38 by David Ortiz in 2016, but he fell considerably short of leading the league, as Koufax did in wins. Ortiz finished tied for eighth, nine homers behind Mark Trumbo. If we were considering Charlie Smith, we’d have to account for the fact that he led the American Negro League with 22 homers, which projects to 52 for a 162-game season, but we’ve already noted that 1929 wasn’t really Smith’s final season. Bill Pierce, Willard Brown, Tom Finley, and Lester Lockett, who led their respective leagues in homers in their final major-league seasons, are all eliminated for the same reason.

But a different Negro Leagues legend is in the running. Josh Gibson led the Negro National League with 13 homers in 1946, his final season before tragically dying that winter of a stroke. He played in just 48 of the Homestead Grays’ 77 league games, so his homer total projects to 27 over a 162-game season. Impressive enough to lead that league, but not a particularly notable figure by itself. Gibson’s ongoing health issues were already taking a toll on his performance. Other than homers and slugging, he didn’t lead the league in any offensive categories, and his 2.4 WAR projects to just 5.0 for 162 games, less than half of Koufax’s mark in 1966.

Shifting to RBIs, the case for David Ortiz in 2016 becomes stronger. He led the American League with 127 RBIs, the most ever compiled in a final big-league season. Some Negro Leagues players who weren’t actually playing their final seasons also managed to lead their league, but the only player besides Ortiz to lead his league in RBIs in his final year was Turkey Stearnes in 1940, when he drove home 33 runs to lead the Negro American League. That projects to just 107 in a 162-game year, well short of Ortiz’s mark, and the rest of his numbers that year weren’t particularly noteworthy.

So how strong a candidate is Ortiz for the title of having the finest final season ever? His homerun and RBI totals are impressive, and he also led the American League with 48 doubles, a .620 slugging percentage, and an OPS of 1.021. But he totaled just 5.2 WAR due to his complete lack of defense as a designated hitter, and even his offensive WAR only wasn’t in the top 10 in the league. He finished sixth in the MVP voting that season, compared to Koufax winning the Cy Young and finishing second in MVP voting. Overall, we’d have to conclude that Ortiz’s final year, though impressive, falls short of Koufax.

There have been some remarkable batting averages posted in players’ final seasons, like Charlie Smith’s .451 mark in 1929 and Tetelo Vargas’s .471 average in 1943, but most of them were achieved by Negro Leagues players who continued their careers in non-major-league venues, including all three of the players who won batting titles in their final big-league seasons. But there is one noteworthy player who hit .382 in his final season that we need to examine more closely.

Joe Jackson, of Black Sox infamy, was third in the AL with that .382 average in 1920. He also led the league with 20 triples, and had an OPS+ of 172, short of Koufax’s ERA+ of 190 in his final year, but still impressive and good for third in the league. He finished the season with 7.5 WAR (or 7.9 in a 162-game year), well behind several other players in 1920, but still the highest WAR total for any hitter in his final season. Others, like the seemingly omnipresent Charlie Smith, posted marks that project to a higher total, but remain ineligible for the title due to their continued careers.

So Jackson may have the best claim so far, but he has the obvious drawbacks of falling short of Koufax in accolades (there was no MVP award that year) and in league-leading performances, plus whatever negative points we care to assign for being banned for life after the season due to his involvement in the Black Sox scandal. Ultimately, we’d have to say that Shoeless Joe isn’t a contender for the title either.

Speaking of the MVP award, no one has ever won the award in their final season. The closest anyone has come was … Koufax, who finished second in 1966.

All things considered, given the parameters we established at the beginning, the answer to the question of who had the finest final season in major-league history seems obvious. Everyone is free to determine their own standards, though, so if you feel nineteenth-century players deserve consideration, then crown Jim Devlin or Dick McBride or some other candidate. Or include Negro Leaguers even if they continued playing elsewhere when their “major league” careers ended. Granting Charlie Smith, for instance, this small dose of attention and fame certainly wouldn’t be inappropriate given the lack of attention he received in life.

But until those rules are redefined, baseball’s finest final season belongs to Sandy Koufax.

, a SABR member since 2001, is a native of Boston and lifelong fan of the Red Sox. He writes a daily newsletter on baseball history at www.lostinleftfield.com, and has contributed several entries to the SABR Games Project and the SABR BioProject, including a contribution to the recent SABR publication One-Win Wonders. His book Cooperstown’s Back Door: A History of Negro Leaguers in the Baseball Hall of Fame, will be published by McFarland Books in February 2025. Paul and his wife live near Kansas City.

SOURCES

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Fangraphs.com for any pertinent information, including career statistics.

NOTES

1 Sid Ziff, “Say It Isn’t So,” Los Angeles Times, April 4, 1965: D-3.

2 Jim Murray, “Arm & Hammer,” Los Angeles Times, May 14, 1965: 43.

3 Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” New York Daily News, August 12, 1965: 283.

4 Alex Kahn, “Dodgers Need a New Star,” Los Angeles Evening Citizen News, November 19, 1966: 10.

5 “Arthritis Finally K’s Koo’s Career,” New York Daily News, November 19, 1966: 251.

6 Jan Leavy, Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy (New York: Harper Perennial, 2003), 238.

7 John Holway, “Charlie ‘Chino’ Smith,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, 1978. Retrieved from https://sabr.org/journal/article/charlie-chino-smith/.

8 Gary Ashwill, “The Death (And Life) of Charles ‘Chino’ Smith,” Agate Type, www.agatetype.typepad.com, April 7, 2011. Retrieved from https://agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2011/04/the-death-and-life-of-charles-chino-smith.html.

9 In 1995 Valentin had one of the most unrecognized great seasons in recent memory, displaying both power (27 homers) and speed (20 steals in 25 attempts) while playing excellent defense at shortstop. He led the AL in both overall WAR (8.3) and defensive WAR (3.0), yet wasn’t selected as an All-Star, didn’t win a Gold Glove, and finished just 9th in MVP voting while his teammate, Mo Vaughn, was given the award. See Mark Feinsand, “This Was a Divisive MVP Choice, So We Re-Voted…” MLB.com, April 2, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.mlb.com/news/re-vote-for-1995-al-mvp-award.

10 Andrew Stoeten, “How Dave Stieb Was Robbed of the 1982 AL Cy Young Award, and What It’s Still Costing Him Today,” The Athletic, November 7, 1982. Retrieved from https://theathletic.com/1317127/2019/11/07/how-dave-stieb-was-robbed-of-the-1982-al-cy-young-award-and-what-its-still-costing-him-today/.