Why Isn’t Sam Bankhead in the Baseball Hall of Fame?

This article was written by Richard “Pete” Peterson

This article was published in The National Pastime: Steel City Stories (Pittsburgh, 2018)

In 1971, Satchel Paige became the first Negro Leagues player to be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. It was the same year the Pirates fielded the first all-black lineup in major-league history on their way to a World Series title.

In 1971, Satchel Paige became the first Negro Leagues player to be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. It was the same year the Pirates fielded the first all-black lineup in major-league history on their way to a World Series title.

Since 1971, over 30 Negro Leagues players and executives have been elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame based primarily on their careers in the Negro Leagues. Those honored include Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, Oscar Charleston, and Judy Johnson, Paige’s teammates on the 1936 Pittsburgh Crawfords—arguably, with its five future Hall-of-Famers, the greatest team in Negro Leagues history. Also in the Hall of Fame are Buck Leonard, Raymond Brown, and Jud Wilson, who, along with Gibson, were part of the dominant Homestead Grays’ team that won nine consecutive Negro National League pennants from 1937–45 and three Negro World Series titles.

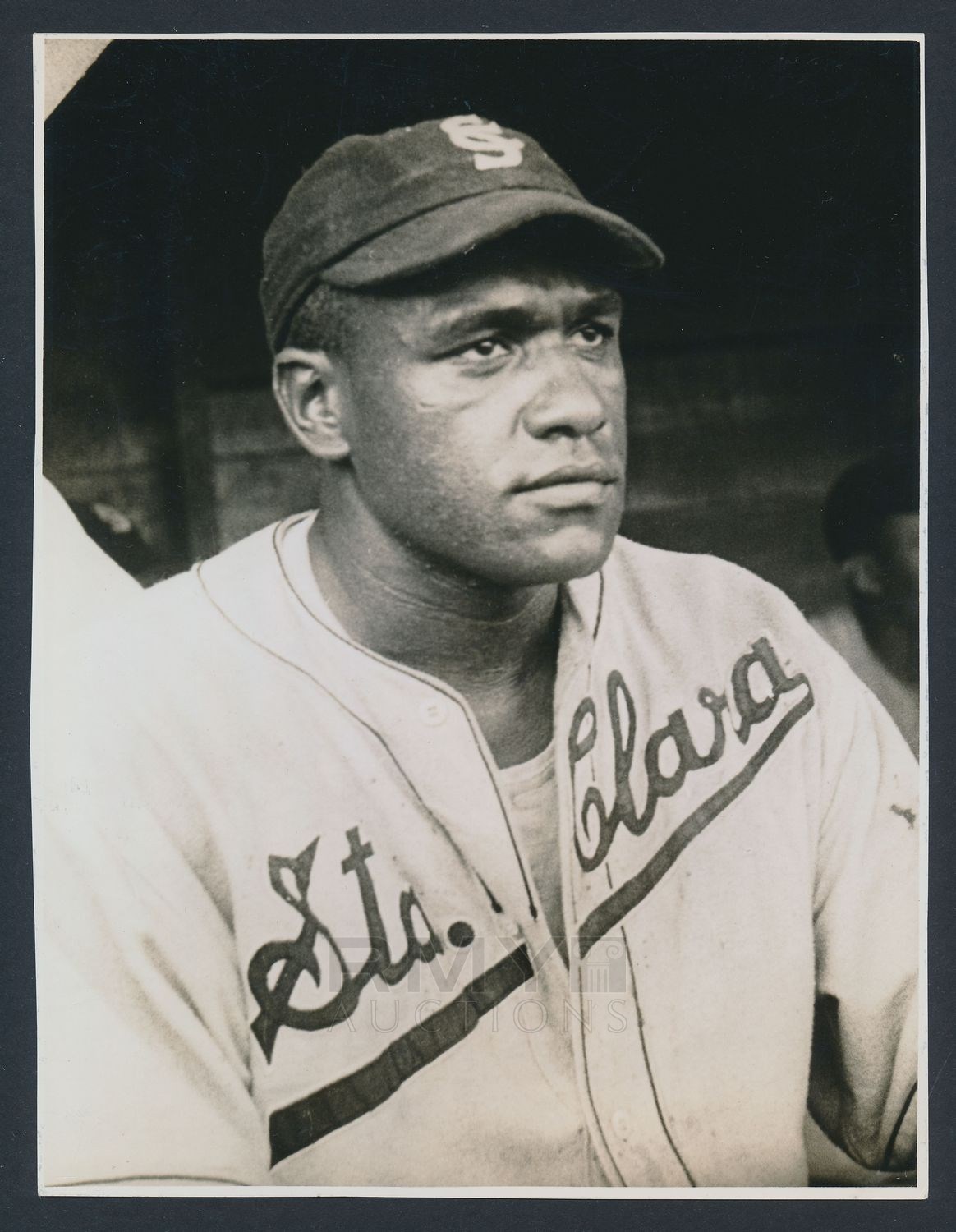

One of the most important members of the great Pittsburgh Crawfords and Homestead Grays teams, however, is not in the Hall of Fame. Sam Bankhead was one of the most accomplished and versatile players in Negro Leagues history. An eight-time selection to the East-West All-Star Game, he was a clutch hitter, an excellent baserunner, and, possessed with a powerful throwing arm, such a skilled infielder and outfielder that he was named the top utility player on the all-time Negro Leagues team selected in a 1952 poll by the Pittsburgh Courier.1

Born on September 18, 1910, in Sulligent, Alabama, Sam Bankhead played his way into professional baseball on sandlots while working in coal mines. He began his Negro Leagues career with the Birmingham Black Barons in 1930. He played with the Nashville Elite Giants in 1930, the Black Barons in 1931, and the Louisville Caps in 1932 before returning to the Elite Giants, where he began to establish his reputation as a star. Bankhead was selected to the first East-West All-Star team in 1933 and played right field for the West. In 1934, he made the West squad in the All-Star Game as a right fielder again. In his eight appearances in All-Star games, he would start at five different positions (second base, shortstop, and all three outfield positions).

In 1935, Bankhead signed a contract with Gus Greenlee to play for the Pittsburgh Crawfords and quickly became a friend to Gibson. In his biography of Gibson, Mark Ribowsky wrote that “Bankhead served as a father confessor, a baseball coach, and a drinking crony.”2 Ribowsky wrote that Gibson’s son, Josh Jr., said that “Sammy was a constant. I’d see a lotta guys come by our house . . . Satchel, Cool Papa, Buck Leonard. All of them great players. But the only guy whose face I got to know was Sammy’s.”3

With Sam Bankhead having his best season, the 1935 Crawfords won the Negro National League pennant. In 1936, while there were no playoffs, they had the best record in the Negro National League. In the 1936 All-Star Game, several Crawfords were in the East starting lineup, including Bankhead, who played left field and had two hits. The Crawfords’ domination of Negro Leagues baseball ended in 1937, however, when Paige convinced several of the team’s best players, including Gibson and Bankhead, to join him with the Dragones de Ciudad Trujillo in the Dominican Republic.

After spending most of the 1937 season with Ciudad Trujillo and playing winter ball in Cuba, Bankhead returned to the Pittsburgh Crawfords in 1938. While the Crawfords were failing financially and soon to leave Pittsburgh, Bankhead made the starting lineup in the East-West All-Star Game, this time as the East’s center fielder, and, at the end of the regular season, he was picked up by the Birmingham Black Barons for the Negro American League playoffs.

In 1939, Cum Posey moved his Crawfords to Toledo. Bankhead began the season with the Crawfords, but ended up with the Homestead Grays and helped the Grays to their third straight Negro National League pennant. In 1940, Bankhead joined a wave of Negro Leagues players, including Gibson, who jumped to the Mexican League, run by the wealthy Jorge Pasquel and his brothers.

After two years playing with the Monterrey Industriales, Bankhead returned to the United States to play for the Homestead Grays, where he had his best years. In 1942, he played in his fifth East-West All-Star Game, this time as the starting second baseman for the East. The Grays won their sixth consecutive Negro National League pennant that year but lost the World Series to Paige and the Kansas City Monarchs.

In 1943, Bankhead was once again the starting second baseman in the East-West All-Star Game and helped the Grays to their seventh consecutive pennant and a World Series victory over the Black Barons. In 1944, he started and played second base and shortstop in the East-West All-Star Game. The Grays went on to win their eighth pennant in a row and, once again, defeated the Black Barons in the World Series.

While he appeared in only 35 games in 1945, Bankhead hit well enough in his limited play to help the Grays win their ninth consecutive pennant, though they were swept by the Cleveland Buckeyes in the World Series. In 1946, the Grays failed to win the Negro National League pennant for the first time in a decade, but Bankhead, at the age of 35, had an outstanding season. He was the East’s starting shortstop in the first of two East-West All-Star games played that year. His younger brother Dan pitched for the West in both All-Star games. The following season Dan became the first black player to pitch in the major leagues since the nineteenth century when he took the mound at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn on August 26 against the Pittsburgh Pirates.

In that year, 1947, when Jackie Robinson crossed baseball’s color line, the Homestead Grays again fell short of winning the Negro National League pennant, but they bounced back to win it in 1948 and defeat the Black Barons in the World Series. It turned out to be the last Negro National League championship for the Grays. With the Negro National League’s star players signing with major-league teams, the circuit folded after the 1948 season.

The Homestead Grays managed to operate for two more years, but one of the most fabled teams in Negro Leagues history played its last games in 1950. During those two years, Sam Bankhead became the team’s player/manager and used his influence to convince the Grays to sign 18-year-old Josh Gibson Jr. to a contract. Since Josh Gibson’s death in January 1947, just months before Jackie Robinson played his first game with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Bankhead and his wife, Helen, had taken responsibility for the care of Josh Jr.4

In 1951, Bankhead made history when he became the player/manager of the minor-league Farnham Pirates in Canada’s Class C Provincial League. He was the first black manager of a minor-league team in organized baseball. While the Pirates finished in seventh place with a 52-71 record, Bankhead, at the age of 40, played in all but one of his team’s 123 games and batted a respectable .274. Bankhead also brought Gibson with him to Farnham, but the teenager batted only .230 in 68 games before breaking his ankle sliding into second base. The injury ended his baseball career.

When Bankhead returned to Pittsburgh, he was out of options in baseball, so he took a job with the city’s sanitation department. When he was joined by Gibson, the two worked together on the same truck, collecting the city’s garbage. Bankhead eventually took a job as a porter in the William Penn Hotel in downtown Pittsburgh. On the night of July 24, 1976, Bankhead got into an altercation at the hotel’s bar that led to someone pulling out a gun and shooting Bankhead to death. The All-Star, the greatest utility player in Negro Leagues history, was dead at the age of 65.

While Sam Bankhead has been passed over year after year by the Baseball Hall of Fame, he was not forgotten by August Wilson, a Pittsburgh native and one of the most important dramatists of the twentieth century. Wilson’s plays have received numerous honors, including Pulitzer Prizes and Tony Awards. His greatest achievement was a cycle of 10 plays, one for each decade of the 20th century, that dramatized the long and continuing struggle of African Americans against racial hatred and injustice.

Fences, often acclaimed as Wilson’s best play and his first to win a Pulitzer Prize, is set in Pittsburgh’s Hill District and takes place in the 1950s, the pivotal decade for the civil rights movement. Rather than a landmark decision or a history-changing moment, Wilson decided to use baseball as the backdrop for his play about the lives of mid-century African Americans.

It’s easy to assume that Wilson based his main character, Troy Maxson, on Josh Gibson, but the likely model was Gibson’s teammate and close friend, Bankhead. Like Bankhead, Maxson, after starring in the Negro Leagues, is working on a garbage truck for the city’s sanitation department. A hard drinker, Maxson is so bitter about never having had a chance to play in the major leagues that he’s building a fence around his Hill District house in a futile attempt to protect his family from the racism that destroyed his dream. He never finishes his fence and dies of a heart attack in his backyard while swinging his bat at a ball made of rags: “Troy assumes a batting posture and begins to taunt Death, the fastball in the outside corner,” Wilson writes. Then Troy says: “Come on! It’s between you and me now!”5

Bankhead made another appearance in the arts when Daniel Sonenberg, resident composer at the University of Southern Maine, decided that opera, with its emotional power, was the perfect medium for the story of a larger-than-life baseball player who was tormented by the forces that denied his greatness and eventually destroyed him. Sonenberg found his story in the tragic life of Josh Gibson, transformed Gibson’s life into an opera, and called it The Summer King.

The Summer King had its world premiere in Pittsburgh on April 29, 2017. While Judy Johnson, Cool Papa Bell, and Double Duty Radcliffe appear in the opera, Sam Bankhead is a lead character. In the final scenes of the opera, he becomes the chronicler of Gibson’s life. At one point, Bankhead intervenes when a group of younger Homestead Grays mock a fading Gibson. He asks them to respect Gibson because of his past greatness.

As he’s dying, Gibson reminds Bankhead about Gibson’s fabled Yankee Stadium home run: “It went a long way. I hope you’ll remember that.”6 At the moment of Gibson’s death, Bankhead steps forward to deliver a powerful aria in memory of the fallen Summer King. In the aria, Bankhead portrays Gibson as baseball’s Moses, who led black players to “the promised land” but never had the opportunity to play there. At the end of the aria, Bankhead laments his own fate now that his king is gone. He asks the question that would haunt Sam Bankhead after his baseball career was over: “What will become of me?”7

Sam Bankhead, like his friend Josh Gibson, never made it to the promised land, never lived the dream of playing in the major leagues. Even with all his flaws, including his struggles with alcohol and drugs, Gibson, in 1972, became the second Negro Leagues player to be elected to the Hall of Fame. Since that time, other Negro Leagues legends, like Cool Papa Bell and Buck Leonard, have entered the Hall of Fame. Bankhead, their teammate and one of the greatest stars in Negro Leagues history, is still waiting to cross over.

RICHARD “PETE” PETERSON — a Pittsburgh native and professor emeritus of English at Southern Illinois University — is the author of Growing Up With Clemente, Pops: The Willie Stargell Story, Extra Innings: Writing on Baseball, and co-author, with his son, Stephen, of The Slide: Leyland, Bonds, and the Star-Crossed Pittsburgh Pirates. He is the editor of The Pirates Reader and The St. Louis Baseball Reader, and co-editor, with David Shribman of Fifty Great Moments in Pittsburgh Sports.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in NOTES, the author consulted the following:

Baseball-Reference.com.

Robert Peterson, Only the Ball Was White (New York: Oxford University Press), 1970.

James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll and Graf), 1994.

Fred C. Bush and Bill Nowlin, eds., Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research), 2017.

Notes

1 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graff, 1994), 52.

2 Mark Ribowsky, The Power and the Darkness (New York: Simon & Shuster, 1996), 164.

3 Ribowsky, 164.

4 Ribowsky, 303

5 August Wilson, Fences (New York: Plume, 1986), 89.

6 The Summer King, music by Daniel Sonenberg, libretto by Sonenberg and Daniel Nester, with additional lyrics by Mark Campbell, Pittsburgh Opera, Benedum Center in Pittsburgh on May 7, 2017.

7 The Summer King.