William Hulbert and the Birth of the National League

This article was written by Michael Haupert

This article was published in Spring 2015 Baseball Research Journal

In 1916, former National League President Abraham G. Mills said at a banquet celebrating the fortieth anniversary of the National League, “I cannot doubt that all true lovers of Base Ball will always cherish and honor the memory of William A. Hulbert.”2 Twenty years later the first honorees were elected to the new Baseball Hall of Fame. Hulbert was not among them, nor would he be for another sixty years.

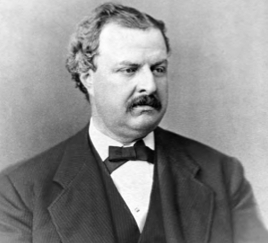

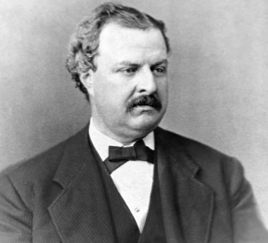

William Hulbert

William Ambrose Hulbert, second president of the National League, owner and president of the Chicago White Stockings, and successful businessman, was passionate about Chicago and the White Stockings. Not so much the latter because he was a devoted baseball enthusiast, but because he was a visionary. He saw what the future for baseball could be, and he recognized the changes that needed to be made to ensure that future. That future revolved around the quality of the game itself, but primarily it focused on the potential profitability of the sport of professional baseball. This is the story of how Hulbert turned a pastime into a business juggernaut.

William Ambrose Hulbert was born on October 23, 1832, in Burlington Flats, New York, a country crossroads located 15 miles west of Cooperstown. His parents moved to Chicago in 1836, where William was raised, along with two brothers. He briefly attended Beloit College, but his primary education was on-the-job training. He worked for his father’s grocery business and a local coal merchant before establishing his own grain trading offices and obtaining a seat on the Chicago Board of Trade.

Hulbert grew up with the city of Chicago. When his family arrived, Chicago was a Midwestern outpost of fewer than 5000 souls. By the time he bought his first shares in the White Stockings in 1870, it had grown to the fifth largest city in the country with a population of just under 300,000. Most of that growth had occurred as he was moving up in the business world. Hulbert celebrated his 18th birthday in a city of 30,000. The tenfold population increase over the next twenty years was astounding. While Chicago grew in size, it did not grow in stature, at least from the viewpoint of the business community. Despite its standing as the fifth largest city, the business community had an inferiority complex, and felt that the eastern cities did not take Chicago seriously. The Chicago business elite were anxious to change that, and a group of them, including William Hulbert, decided that baseball would be one way to accomplish that change. They took notice of the national attention the Cincinnati Base Ball Club’s 1869 tour had drawn to the Queen City, and decided a professional team would help draw the attention and respect they felt Chicago deserved.

Hulbert purchased three shares of the White Stockings ball club, which entered the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players, the first professional sports organization in the United States, which began play in May of 1871. The White Stockings inaugural season in the association was derailed by the great Chicago fire that burned 3.3 square miles of the city in October of that year. Among the victims of the fire were the team’s home field, Union Baseball Grounds at Lake Park, along with the team’s uniforms and equipment, and the homes of most of the players. Despite this disaster, the team finished out the season on the road, using equipment and uniforms borrowed from the rest of the league. However, it was the last championship game they would play until 1874. By then Hulbert had risen from minority owner to team secretary, a position that included responsibility for marketing and publicity. Hulbert demonstrated a flair for this, especially after the team moved into the National League. After one year as secretary, Hulbert was named president of the club. It was from this position that he made his most dramatic and important changes, not just to the team, but to professional baseball as an institution.

The National Association

The National Association (NA) was the first professional baseball organization. As such, its founders recognized the potential of baseball as a profitable business. Unfortunately, the way in which it was organized would prove to be too unstable to produce the expected profits. The NA was organized in March 1871. The clubs had to visit each other during the season, but they were on their own to schedule the specific dates of the matches. This would prove to be problematic. The entry fee was only $10 per team. This proved to be another problem. The NA featured some clubs that were run as cooperatives.3 These clubs were for the most part loosely organized and run more like the amateur clubs of old than a profit oriented business. Though they may have been small in number, an association is only as strong as its weakest franchise. This form of organization was the third strike against the success of the NA.

Cooperative clubs did not establish player payrolls. Instead, they split the gate, meaning that a poor turnout resulted in a meager payday. The low entry fee attracted clubs from small towns, which only exacerbated the low turnout problem. This not only resulted in low pay for the players, but made them a bigger target for gamblers looking for a little insurance on their bet. Hippodroming—the practice of throwing games- was perceived to be a widespread problem in the NA.

Low entry fees encouraged small, poorly financed teams to take a flyer on the association. They were unable to compete at the professional level however, and frequently folded before finishing the season. Twenty-four different teams played in the NA over the course of its five-year history, half of them appearing for only one year4, including small towns such as Keokuk, Iowa, Fort Wayne, Indiana, and Middletown, Connecticut. Another five teams lasted only two years, and only three franchises survived all five years (Athletic, Boston, and Mutual).

In addition, small towns, which begat small crowds, proved unappealing to large town teams. This resulted in teams reneging on their agreements to play in small towns, finding it more profitable to stay at home and play exhibition games instead. An association without fixed schedules made it easier for teams to forego scheduling return games in smaller and more distant towns.

In 1875 for example, three of the nine eastern teams (Brooklyn, New Haven, and the Centennials), did not make a trip west to face any of the four western clubs. The Centennials folded after only a month of play, but the other two teams played the full season, hosting western clubs on multiple occasions. And the six eastern teams that did make a western swing did not always reciprocate the games the western teams played in the east. For example, the St. Louis Browns visited New York on two occasions, playing a total of six games there, but the Mutuals only played three games in its one St. Louis visit.

Gambling was not the only common vice associated with professional baseball. Alcohol flowed freely both in the stands and outside them, and all too frequently, it even spilled onto the field. Drunken behavior, which often led to rowdiness, was a common occurrence inside the ballpark.

Revolving was another issue that Hulbert abhorred. Revolving was the practice of players jumping teams from one season to the next. While he viewed this in itself as problematic, the bigger problem was that many players signed a new contract for the following season during the current season, while still under contract to another team. This led to credibility issues and further increased the attraction to gamblers. After all, if a player is contracted to another team for next year, it might be in his best financial interests to let up a bit when playing his future employers this year.

By 1875, after only five years in operation, the National Association was in trouble. It was weak and unable to play a complete schedule, or control the player jumping, rowdy behavior and gambling. The integrity of the games was so low that on occasion law enforcement officials were compelled to post signs at ballparks announcing that games played between the competing teams should not be trusted.5 As the problems became more obvious the fans began to lose interest. Attendance declined each year of the organization’s existence.6 The time was ripe for a stronger, centrally governed league.

Hulbert was never comfortable with the National Association. As a businessman he recognized its many faults. As a proud Chicagoan, he believed that Midwestern teams, his White Stockings in particular, were slighted by the eastern-dominated organization. And as a club official, he was frustrated by the constant revolving of players between teams. He complained that whenever Chicago signed a good player, he was likely to be stolen away by an eastern club. This complaint was bolstered by the fact that five members of his 1874 squad, including Davy Force and Levi Meyerle, the team’s top two hitters, were signed by Philadelphia teams for the 1875 season.

Hulbert proved that he could give as well as take when it came to revolving. During the 1875 season he secretly signed Albert Spalding, Deacon White, Ross Barnes, and Cal McVey from Boston, and Adrian C. “Cap” Anson from the Athletics for his 1876 ball club. Both Boston and the Athletics were clubs that he intended to invite to be charter members in his new improved league—one that would outlaw the practice of revolving.

After organizing the new league, Hulbert did affect a dramatic decrease in revolving, even before the reserve rule was created after the 1879 season. A total of 211 players suited up during the five year history of the National Association, but only 138 of them played more than one season. Of those 138, only 19 percent played for only one team during their career. Half of the players changed teams three or more times, with four percent changing teams every year of the five year existence of the organization. By contrast, in the first five years of the NL 27 percent of the players who were in the league for at least two years never changed teams, and only 22 percent changed teams more than twice.

As a businessman, Hulbert recognized an opportunity for profit and the shortcomings of the current structure in attaining that profit. The time was ripe to seize the initiative in the baseball market. Baseball was popular, familiar, and widely accessible to the general public. On larger fronts, the growth and development of the American economy was making the landscape for entertainment more inviting. Since the middle of the 19th century the average workweek had been declining and the average wage increasing. Increasing urbanization and the growth of intracity mass transportation meant that more people were in closer proximity to entertainment venues, and it was becoming cheaper and easier to get to those venues. Higher salaries and more free time meant Americans had the time and the money for entertainment, and baseball was well situated to satiate that growing demand. Hulbert knew that the current structure would not allow for it. Rather than let the opportunity pass, he did something about it.

William Hulbert was not the only person to recognize the troubles with the NA. Henry Chadwick had been publicly railing against gambling and rowdiness since before the NA even began. In the official association publication of 1873 he said that “when the system of professional ball playing as practiced in 1872 shall be among the things that were, on its tombstone—if it have any—will be found the inscription, ‘Died of Pool-Selling.’”7 And as early as 1867 he wrote that the model ballplayer was one who was “a gentleman on all occasions, but especially on match days, and in doing so, he abstains from profanity [italics original] and its twin and evil brother obscenity.”8 Hulbert did not immediately come to the conclusion that the NA was broken and could not be fixed. While he may have been harboring such thoughts, he did not begin to act on them until after he had been appointed secretary of the White Stockings in the fall of 1874.

As the secretary, he was appointed to represent the team at the organization’s annual meeting in Philadelphia, where he was named to the league rules committee.9 The Chicago Tribune, in announcing that Hulbert would represent the team, foreshadowed events under Hulbert’s leadership when it commented that he held “some very pronounced ideas on the punishment which should be meted out to “revolvers,” and will make an excellent representative generally.”10 While there he “saw that a radical reform should be affected, and an entirely new departure made, to place the national game on an enduring footing. The idea of a National League originated then and there…and before he left Philadelphia he had thought out the general plan.”11

The National League

The concept of the National League may have begun with Hulbert’s plans during the 1875 season, but the first concrete steps were taken on December 16 and 17 of that year when he convened a secret meeting with representatives of four NA clubs. Walter Newman Haldeman and Charles E. Chase, representing Louis-ville, Nathaniel Hazard and Charles A. Fowle of St. Louis, and John P. Joyce from Cincinnati met with Hulbert and Spalding in Louisville.12 Hulbert was able to woo the westerners by appealing to their resentment over their poor treatment at the hands of the eastern clubs on issues such as revolving and the failure of eastern clubs to make all their western swings.

The next step was to recruit the targeted eastern clubs. This was a more delicate process but Hulbert handled it masterfully. He needed to convince four eastern clubs to join the league for geographic balance and marketing power. This would be tricky because unlike the western teams, the eastern clubs did not have a chip on their shoulder. The NA had worked well for them, so they weren’t necessarily looking to go in a new direction. Hulbert had already identified the four eastern clubs he wanted. The eastern representatives who were invited were not aware of the extent of the agenda, save for Harry Wright who, for nearly a year, had been in correspondence with Hulbert, exchanging ideas for ridding the NA of its weaker clubs.13

The clubs were to send representatives to a meeting according to a letter to each dated January 23, 1876:

The undersigned have been appointed by the Chicago, Cincinnati, Louisville and St. Louis Clubs a committee to confer with you on matters of interest to the game at large, with special reference to the reformation of existing abuses, and the formation of a new association, and we are clothed with full authority in writing from the above named clubs to bind them to any arrangement we may make with you. We therefore invite your club to send a representative, clothed with like authority, to meet us at the Grand Central Hotel, in the city of New York, on Wednesday, the 2d day of February next, at 12n. After careful consideration of the needs of the professional clubs, the organizations we represent are of the firm belief that existing circumstances demand prompt and vigorous action by those who are the natural sponsors of the game. It is the earnest recommendation of our constituents that all past troubles and differences be ignored and forgotten, and that the conference we propose shall be a calm, friendly and deliberate discussion, looking solely to the general good of the clubs who are calculated to give character and permanency to the game. We are confident that the propositions we have to submit will meet with your approval and support, and we shall be pleased to meet you at the time and place above mentioned.

—Yours respectfully, W.A. Hulbert.

Chas. A. Fowle.14

While popular mythology has Hulbert taking the eastern representatives by surprise with his agenda and locking them in a room to present it, the actual invitation suggests something otherwise. By inviting them to confer about the “formation of a new association,” it seems evident that he was tipping his hand.

The meeting of the National Association’s Grand Council is considered as the founding meeting of the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs (NL). Each of the eastern teams, who were meeting with Hulbert on this topic for the first time, sent representatives. The west was represented by Hulbert and Charles Fowle. They held the proxy votes for Louisville and Cincinnati. Each of the eastern franchises was represented by owners: William Cammeyer (Mutuals), G.W. Thompson (Athletics), Morgan Gardner Bulkeley (Hartford), and Nicholas Taylor Apollonio (Boston) and William Henry “Harry” Wright, who was allegedly there to present the proposed changes to the playing rules. Also present were Lewis Meacham of the Chicago Tribune, the only reporter invited, and Nicholas Young, secretary of the NA, and soon to be secretary of the new NL.15

Dramatic accounts of the meeting tell of Hulbert locking the door and telling the assemblage, “Gentlemen, you have no occasion for uneasiness. I have locked that door simply to prevent any intrusions from without, and incidentally to make it impossible for any of you to go out until I have finished what I have to say to you, which I promise shall not take an hour.” The story goes on to say that Hulbert mesmerized the gathered moguls and used his peerless salesmanship to convince everyone of his case, and then with a flourish, he produced an already completed league constitution, which was enthusiastically signed by everyone. While no eyewitness account has ever disputed the basic facts concerning who was invited, what was pitched, and that it was taken hook line and sinker, neither has any ever mentioned the locked door or the stirring sales pitch. Spalding tells this story complete with quotation, but he was not there.16

While the eastern clubs were necessary to the NL, each came with some baggage. Boston, the staunchest ally of the group, was a stock club, with more owners than players. A large ownership could mean a lack of involvement by any individual, since no one had sole control. A single-owner team, which Hulbert favored, was more likely to be the constant and sole focus of the owner. Hulbert himself was one of more than thirty stockholders of the White Stockings, which had been reincorporated just a few months prior. This would not be the first example of his believing that what was good for the goose was not necessarily also good for the gander.

Despite having recently raided the Boston roster of its stars, Hulbert needed and courted Boston for his new league. Boston’s baseball history was rich, and Harry Wright’s reputation was unparalleled in baseball. Having Boston and Wright aboard was critical to the success of the new league. Because Wright was so concerned about the glaring weaknesses of the NA and reforming baseball to save it, he was willing to overlook the loss of his stars and ally his interests with Hulbert.

The city of Philadelphia presented a problem. There were three NA teams, and the city had a reputation as a hotbed for gamblers and crooked players. The Athletics were Hulbert’s choice. But their history of raiding each other’s rosters would have to be papered over. The Athletics were not happy with Chicago for signing away Adrian Anson, their top player, and Hulbert still held a grudge against the Athletics over the signing of Davy Force the previous year.

The White Stockings and Athletics had been battling over players for years. In 1871 Ned Cuthbert signed with the White Stockings only to jump back to Philadelphia before ever playing a game in Chicago. He ultimately returned to Chicago in 1874. During the 1873 season Chicago signed Levi Meyerle to a secret contract for the following season. He tried to renege on the contract, but ended up playing in Chicago in 1874. The following year Meyerle and Davy Force were signed by Philadelphia clubs. Hulbert detested Athletics owner Charles Sperling so much that he swore they would not be allowed to join the NL unless he was expelled (which he ultimately was before the NL season began).17

Despite his personal animosity toward Philadelphia, Hulbert needed a team there. The market was too large and its baseball history too rich to leave to the NA. The Athletics needed Hulbert as well. There were several teams in the city, so joining the NL would give them geographic exclusivity at the top level, which was worth swallowing the fact that arch enemy Hulbert was involved. In the case of Philadelphia, Hulbert put the practical matter of league survival and business profits ahead of personal animosity. It was a decision he would ultimately come to regret.

The Mutuals had a reputation for employing shady players, and Hartford was smaller than the minimum sized city called for in the constitution. But New York was the largest city in the US and Hartford had Bulkeley, whose prestige and contacts would serve the league well. He was better known in business and political circles than baseball, having organized the United States Bank of Hartford in 1872 and served on the Hartford Common Council and as a city alderman. In 1879 he would take over leadership of Aetna Life Insurance Company, founded by his father in 1853. He was elected mayor of Hartford in 1880, governor of Connecticut in 1888, and then represented the state as a US senator 1905–11. Even though most of that was in the future, he already had a stellar reputation. He was from a prominent and wealthy New England family, and a successful businessman in his own regard. Bulkeley’s reputation, contacts, and business acumen were coveted by Hulbert for the new league.

Hulbert appealed to the owners, businessmen all, by using some simple economic logic. If the businessmen ran the teams and the players concentrated on playing ball, each party could concentrate on doing what they did best and everyone would be better off. The geographic exclusivity he promised to each club appealed to the owners as well. Exclusivity meant monopoly, and monopoly meant profit. Establishing the NL as the premier professional league, with entry strictly controlled by the monopolists themselves, also appealed to their sense of profits. If the new league was recognized as the premier assemblage of baseball talent then it would be able to attract a greater percentage of the better players, and with no equals to bid them away, it would lower the payroll burden, leaving a larger percentage of the revenues for the owners. Another reason to concentrate the quality of talent at the top was to reduce the number of poor drawing games played against low quality competition in small towns.

League membership was restricted to one team per city and mandated a minimum population of 75,000 (unless unanimously voted otherwise by the league—this is how Hartford gained admission). League teams were prohibited from hiring expelled players and under no circumstances could they play a game in another league city against anyone but the league team headquartered in that city. This was another means of reducing competition through geographic exclusivity.

Gambling was not tolerated by players or fans, nor was it allowed on the premises or any facilities owned by the member clubs. Teams were required to pay $100 annual dues—ten times what was required by the NA, and complete their season schedule. These two rules were the bedrock of the league and were enforced by the threat of expulsion.

Hulbert impressed upon those assembled that reforms were needed to prevent the demand for baseball from decreasing. Additional reforms included an end to revolving, a ban on alcohol at the ballpark, and no more Sunday ball. The latter item was the toughest sell because Sunday games were usually the best attended. Hulbert convinced his brethren that while a great deal of money could be realized in the short run by playing on Sunday, honoring the Sabbath would carry with it valuable moral cachet, which would result in greater long run profits.

The constitution was approved by the eight charter members at the meeting. Board members were chosen by lot. In order, the five names drawn were Bulkeley (Hartford), Apollonio (Boston), Cammeyer (Mutual), Fowle (St. Louis), and Chase (Louisville). The legendary version of the meeting includes the detail that names were drawn from a hat, and it was decided that the first name drawn would be president of the league, which is how Bulkeley became president. Another story has Hulbert nominating Bulkeley to appease the eastern clubs. Like many legends, this one has a kernel of truth. The directors were indeed chosen by lot. This was already predetermined by Article IV, section 1 of the league constitution, which had been approved before the directors were chosen. According to the constitution the board would be determined by random drawing, and then the directors would elect a president from among their number. There is no specification that the first name drawn would be president. Since Hulbert was not a member of the board, it is more likely that his ally Fowle would have made the nomination.

It is unlikely that Hulbert would have allowed the league presidency to be determined by lot, as it would have left the leadership of the new league totally to chance, and nothing else he did was left to chance. It is possible that Bulkeley was suggested for the honor on the strength of his name having been drawn first. Bulkeley had a sterling reputation as a businessman, but only marginal and shallow baseball experience and interest. For those very reasons, Hulbert was likely to have wanted him as the figurehead president, thus allowing Hulbert to wield the real power from the background, which is exactly what happened. After the names were drawn a motion was resolved that the first name drawn be declared President of the League for 1876.18

An example of how Hulbert was perceived as the real power in the league can be seen in the appeal of the New Haven club. New Haven was shut out of the NL because it was too small. Hartford, which was even smaller, was allowed in because the exception clause required a unanimous vote, which they got. In February of 1876 New Haven sought to file a personal appeal, and sent their club secretary to Chicago to make the case to Hulbert. Hulbert was not the league president, nor even a board member, but New Haven knew who was pulling the strings. Without Hulbert’s approval, there was no getting into the league. Their trip proved fruitless.19

The meeting concluded with the resignation of the invited teams from the NA and their formal inclusion in the new NL. The clubs did so in a formal declaration stating that “the abuses which have insidiously crept into the exposition of our National Game, and…the unpleasant differences which have arisen among ourselves growing out of an imperfect and unsystematized code” led to this action.20 The break was simple and clean, no need to vote anyone out of a league. Just resign from the old organization and form a brand new one.

The new league differed from the NA in many ways, none more important than reputation. The constitution laid out very specific regulations pertaining to gambling, alcohol, and scheduling. It was important that the league live up to its constitution, and it would prove adept at doing so, thus slowly but surely rebuilding the damaged credibility of professional baseball. Over the first five years of the league each of these issues would become a high profile test of the will of the league to make very difficult decisions.

Hulbert supported a league wide requirement of 50 cent admissions because he felt lower prices cheapened the game. Higher admission fees allowed the teams to pay players higher wages, making them less likely to succumb to gamblers’ entreaties. The NL established a 15 cent per ticket share for visitors. Hulbert preferred the percentage gate system to a flat fee system for visiting clubs because he felt it better supported weak clubs.

The success of the new league required that it attract the top talent. Hulbert claimed that eight was the most teams that could survive in an upper-echelon league given the quantity of available talent. The record of NL teams in exhibition games with non-league teams seemed to suggest otherwise. In 1876 NL teams lost 37 games to outside clubs, nearly one-third of the total they played. In 1877 the newly formed International Association squared off against NL opponents more than 100 times and won as often as they lost.21

A more compelling reason for limiting the size of the league was to insure financially stable franchises. Identifying eight such clubs proved to be a vexing problem. During its first decade of existence 21 teams were members of the NL at one time or another. In fact, by its third season only two of the original eight franchises remained in the league. The situation became so perilous that at one time Hulbert chaired a two man committee authorized to appoint any outside club in good standing as an emergency replacement in case a league team folded.22

The new league may not have been the knight in shining armor to baseball’s maiden in distress that the folklore paints it, but it did do three important things that have made the baseball business the cash cow that it is today. First, they separated production (on field play) from management (front office). This not only took advantage of the different skills of two distinct groups of workers, but also concentrated the control and the profits in the hands of a small number of businessmen.

Second, using the puritanical arguments about observing the Sabbath and taking the moral high ground, the league cleansed the bleachers of the rough and rowdy crowd that gambled, drank, swore, and fought in the stands. Those same folks were less likely to attend games on other days because they were at work. Raising the ticket price to 50 cents from a quarter priced this lesser element out of the market. Covered grandstands, ladies in attendance, padded seats, and season tickets all operated as a form of conspicuous consumption that helped attract the coveted higher income classes into the ballpark.

Hulbert sought to make ballparks attractive to women. Not just any women, but upper class “genteel” women. Women would not visit the ballpark if there was rowdy behavior on the field and in the stands, which was the case when alcohol was commonplace before, during, and after the games. Less booze meant less fighting and hooliganism, which meant more women. And the more women in attendance, the more of a mollifying effect they were likely to have on the male behavior, further domesticating the ballparks. Hulbert was not a pioneer; he was following a profitable example set by eastern vaudeville houses, which had discovered that a family atmosphere appealed to a larger crowd.23

Finally, the idea of geographic exclusivity, now the bulwark of any professional league, was established. It was the innovation of Hulbert for the National League and it served two purposes. The first was to carve out monopoly territories for the owners, boosting their profit potential. Geographic exclusivity created the monopoly conditions that allowed the league to raise ticket prices to 50 cents. Second, once established, it helped the league keep interlopers out and profits up.

Hulbert also instituted the first fixed scheduling. This was an important innovation that helped the league control its requirement that all teams play their full schedules. By establishing a fixed schedule, in one fell swoop Hulbert eliminated the excuse that any team could not find a mutually agreeable date to travel to another city to finish its schedule. This made it tougher for teams to renege on their obligations and much easier for the league to monitor and enforce scheduling compliance. This issue was to come up much sooner than expected, and have dramatic results for the league. Hulbert also insisted on uniform contracts (though not right away), established a roster of umpires, and championed the reserve rule, though it was not strictly his idea.

Writing these things into the constitution and issuing press releases to brag about them was one thing. As the experience of the National Association demonstrated, enforcing them was quite another. The issue of enforcement was where Hulbert made his strongest stand. Over the first five years of the league his resolve was tested several times, but three incidents stand out above all others: the eviction of the New York and Philadelphia franchises after the 1876 season, the lifetime expulsion of four Louisville players in 1877, and the eviction of Cincinnati in 1880.

The Eviction of New York and Philadelphia

The first hint of major trouble for the new league occurred toward the end of the inaugural season, when neither the Athletics nor the Mutuals completed its schedule. Neither was willing to make its second (and final) western swing. The Athletics told Chicago and St. Louis they could not afford a trip west but offered to host Chicago to complete the schedule. They offered 80 percent of the gate to Chicago and St. Louis if they would come east.24 Hulbert refused.

Likewise, William Cammeyer reneged on the Mutuals’ final western trip for reasons of financial hardship. Hulbert reacted differently to the Mutuals, whom he needed more desperately in his league. Chicago and St. Louis each offered Cammeyer a $400 guarantee for making the trip for a two-game series in Chicago and three in St. Louis. Cammeyer refused, and neither the Mutuals nor the Athletics finished its schedule, setting up a dramatic postseason showdown.25

According to the league constitution, both would be expelled. However, abandoning the two largest cities in the league would be a risky move. Hulbert felt strongly that the integrity of the league must be upheld, and he began posturing for expulsion well before the league meeting in December.

In reference to the upcoming meeting, Hulbert wrote to Boston owner Nicholas T. Apollonio about how important it was to the league that every club play out its schedule and that no club employ a man expelled from another club. “I know of no other possible use for a combination of clubs except to enforce these two things,”26 said Hulbert, clearly stating his intentions before the meeting. Hulbert intimated that he intended to take a hard line, and was lining up support.

The first order of business at the annual meeting was the election of a new president. President Bulkeley was not at the league meeting, having previously offered his resignation in order to focus on his political career. After the board formally accepted his resignation, Hulbert nominated Nicholas Apollonio as his replacement. Apollonio refused, indicating that he was unsure he would still be involved with the team much longer. In fact, he was already in negotiations to sell the club, a fact that Hulbert was almost certainly aware of.27 After Apollonio demurred, Hulbert was then unanimously elected to replace him.

As expected, the major topic of business was the fate of the New York and Philadelphia franchises. Taking the moral high road and holding strictly to the league constitution, Hulbert argued that expulsion was necessary for the survival of the league, its reputation hanging on the outcome of the expulsion vote. The Chicago Tribune called the meeting “the most important event in base-ball since the formation of the National League.”28 Hulbert carried the day, convincing the other owners that failure to enforce the constitution was tantamount to a death sentence. If the National League did not enforce its own rules, it would be no better than the organization it had abandoned just a year earlier, and would inevitably suffer the same fate as the National Association.

Cammeyer left the league without appeal. He did so, however, having already arranged to lease his Union Grounds to the Hartford club for the 1877 season, thus preserving his primary reason for being involved with baseball—profits. This also made it easier to expel the Mutuals, since the league would still have a presence in New York. Neither team was immediately replaced, and the NL played with six teams for the 1877 season.

The Louisville Four

At the end of the 1877 season Hulbert presided over a moral crackdown on hippodroming, permanently banning Louisville players George Hall, James Devlin, Bill Craver, and Al Nichols from the league for throwing games during the season. He used the situation to his fullest advantage, proving once again that the league was serious about upholding its constitution. Shortly after the announcement of the Louisville debacle, he wrote to Hartford manager Bob Ferguson: ”Certainly nothing can be lost to the legitimate game by the conviction and punishment of the thieves and scoundrels who infest it and by their presence as players bring disgrace and contempt upon it…Now it strikes me, the exposure and conviction upon their own confession of the four men named, makes our forthcoming League meeting an excellent time and place to strike an effective blow.”29

At the league meeting in December of 1877 the directors unanimously expelled the players. It wasn’t just the Louisville franchise that suffered from the scandal, but St. Louis as well. They had contracted with Devlin and Hall for 1878. St. Louis had been in financial straits and looked to Devlin and Hall for redemption. When they were expelled, the team gave up and resigned from the league. Their resignation was accepted shortly after the league expelled the players for life. St. Louis would not return to the NL until 1885, three years after the St. Louis Brown Stockings established a franchise in the American Association.

Though Louisville was represented at the December meeting and participated fully in all deliberations, there was no news coming out of the city all winter about roster moves for the next season, and indeed, in March they withdrew from the league. The Louisville Commercial reported that the team folded because they “were so thoroughly disgusted with the conduct of the players last season that a call upon them now would meet with a cold response,” adding that “the rascality of last year’s players and the general conviction that dishonest players on other clubs were more the rule than the exception.”30

If ever the new league was going to collapse, it should have been following the 1877 season. The NL had kicked out teams in the two largest cities after the first year, dropping membership to six teams. Then in 1877 it endured a player gambling scandal and the midseason bankruptcy of the Cincinnati club, followed by the loss of two more franchises before the opening of the 1878 season. Heading into its third season, the league had only two of its original franchises in the fold (Boston and Chicago), three of the four remaining franchises were in their first year of existence (Indianapolis, Milwaukee, and Providence) and the Cincinnati entry, while still in the same city, was a replacement franchise for the one that had folded in June. Hartford had also dropped out of the league after the 1877 season, having played that year in Brooklyn as the Brooklyn Hartford. And yet the league survived. Hulbert’s moves, which directly caused the exit of the Mutual and Athletic clubs and indirectly led to the loss of Louisville and St. Louis, strengthened the league in the long run. Despite the short run chaos of musical franchises, the league was establishing credibility. Ousting teams and players for failing to abide by the constitution bolstered the reputation of Hulbert and the NL, which proved to be of great value in the long run.

The Eviction of Cincinnati

The 1880 season featured another team expulsion, this time the Cincinnati club. Cincinnati had been making a regular habit of leasing their ballpark out for Sunday games. This was a constant source of irritation to Hulbert, since it flouted the spirit of the Sunday prohibition. To make matters worse, beer was sold at those Sunday games—another Hulbert taboo. The final strike against the Redlegs was their desire to do away with the reserve rule that Hulbert championed.

Late in the 1880 season Cincinnati Enquirer sports editor O.P. Caylor blasted Hulbert in print for refusing to allow beer sales. He threatened to orchestrate Hulbert’s ouster from the presidency, and failing that, to organize a whole new league.31

In a rant against beer and Sunday games, the Chicago Tribune chastised Cincinnati. The Tribune opined that “the question both of Sunday games and beer-jerking is not one of morals, but of sound business policy. Base-ball, outside of Cincinnati, is supported by a class of people by whom these practices are regarded as an abomination—a class of people whose patronage is of infinitely greater value in dollars and cents, let alone respectability, than that of the element to whom beer is an attraction and a necessity.”32

At the league meeting in December the constitution was rewritten to prevent the playing of any [emphasis added] games at league parks on Sunday. It now read no “club shall take part in any game of ball on Sunday or shall allow any game of ball to be played on its grounds on Sunday.”33 At the same meeting Cincinnati was expelled for failing to satisfactorily guarantee that it would observe the new constitution.34

Caylor did not go quietly after the ouster of the Cincinnati franchise from the NL following the 1880 season. He threatened to start a new league, scheduling a meeting for its planning. However, nothing came of it that year. But the following fall the American Association (AA) was born. The AA was organized on an anti-Hulbert platform. It promoted Sunday games, beer sales, and discount admission prices of 25 cents. Hulbert would not live to see it.

The International Association

In 1877, after abolishing the two largest cities from the league, Hulbert addressed another potential crisis when a competing organization was formed. In February 18 independent teams gathered in Pittsburgh and formed the International Association of Professional Baseball Players (IA) to replace the NA. Membership was $10 or $25 if the team wanted to compete for the championship. A total of 23 clubs signed up for the league, seven paying the higher fee to compete for the championship.35 The IA wasn’t interested in going to war against the NL. After all, its clubs, all of which existed prior to its formation, profited greatly from the exhibition games regularly scheduled with the NL. Rather, the formation of the IA was in response to the demand for baseball in the many cities ignored by the NL. The IA included teams from towns ranging in size from Auburn, NY to St. Louis. Most of the clubs were run as cooperatives, and the players earned a share of the gate, not a salary.

Though it was a loose-knit organization, resembling the NA in its minimal membership fee and the size of its venues, the NL took it seriously. They allowed NL teams to schedule exhibition games with IA teams, but forbade the playing of those games on NL grounds.36

The “League Alliance” was the most effective response to the IA. The plan was actually conceived by Abraham Mills, a future league president and eventual employee of Hulbert’s. In exchange for a $10 fee and their promise not to sign any player on an NL roster, alliance clubs received reciprocal respect for their player contracts and territorial rights. The alliance tied IA clubs to the NL with the promise of mutual respect for player contracts and bans on ineligible players. Twenty-nine clubs joined the alliance in its first year, including future MLB cities Minneapolis, St. Paul, Indianapolis, Milwaukee, Providence, Syracuse, Troy, and the once and future Philadelphia.

So who would join under such circumstances? Any team that saw the future: the National League was the standard bearer of quality baseball. The path had been blazed, and the future was the National League. Better to ally with it than be crushed underneath it. While the NL was not yet the behemoth that it would become, the impression that Hulbert gave about the inevitability of the success of the NL under his guidance was enough to convince several teams to ally with him.

Hulbert used the alliance approach as opposed to a more confrontational one for two reasons. The first was simple business: cooperation was more profitable than confrontation. After all, few IA teams were in NL cities, and those that were did not pose much threat. A secondary, though non-trivial reason for the cautious approach was that while NL players were better paid, the cooperative format of the IA offered players more control over their fate. The NL had to move slowly against this foe lest they force their hand and lose players to the more labor friendly league. Touting higher pay and the ability of players to concentrate on playing ball as opposed to front office details worked to the NL’s advantage. After all, most ballplayers were not businessmen, and did not necessarily want to be.

Eventually the lure of higher salary won out over the ability to have more control, and the best players gravitated to the NL. As the NL increased its number of league games, leaving fewer opportunities to play exhibitions, it left fewer chances for IA players to compete against top notch competition, making the league even less attractive to the best players, and hence paying customers. The IA slowly faded away, folding in 1880.

The Hulbert Legacy

William A. Hulbert fell ill in the fall of 1881 and died of heart failure on April 10, 1882. Though it took 113 years after his death, William Hulbert was eventually inducted into the Hall of Fame. No inductee ever had to wait as long for the honor as Hulbert did. His enshrinement is a testament to his contribution to the game. But perhaps more than that, his legacy is the institution that still stands today. The National League, which in 2014 concluded its 138th season, has successfully beaten back the challenges of the International Association, the Players League, the Union Association, the American Association, and with American League, the Federal League. Furthermore, all major sports leagues in North America are built on the same foundation established by Hulbert: geographic exclusivity, separation of management and players, fixed schedules, a roster of umpires/referees, uniform contracts, and in the beginning, the reserve rule. William Hulbert may have been forgotten for a century after his death, but his imprimatur on professional sports yet endures.

MICHAEL HAUPERT is Professor of Economics at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Greg Erion, John Thorn, participants at the 2013 Economic and Business History Society conference, the 2014 Popular Culture/American Culture Association annual meetings, the 2014 Society for American Baseball Research convention, two anonymous referees and Clifford Blau for helpful suggestions and comments, and Richard Smiley for valuable assistance in finding newspaper articles. Any remaining errors or omissions are solely my responsibility.

Notes

1. I would like to thank Greg Erion, John Thorn, participants at the 2013 Economic and Business History Society conference, the 2014 Popular Culture/American Culture Association annual meetings, the 2014 Society for American Baseball Research conference, two anonymous referees and Clifford Blau for helpful suggestions and comments, and Richard Smiley for valuable assistance in finding newspaper articles. Any remaining errors or omissions are solely my responsibility.

2. Abraham G. Mills papers and correspondence, National League, 1891–1926, series III folder, National Baseball Library.

3. Harvey Frommer, Primitive Baseball: the First Quarter-Century of the National Pastime, New York: Atheneum, 1988, 130–31.

4. Teams did not always finish the season that they started. And when they did finish, they didn’t necessarily play a full schedule. In fact, in no season did all teams play even close to the same number of games. The best year was 1871 when Ft. Wayne played 19 games and New York played 33 (the average was 27.8). The worst was 1875 when Hartford played 82 games, Keokuk played 13, the league average was 51.5 and three of the 13 league teams played less than 20 games.

5. Bill Mooney, “The Tattletale Grays,” Sports Illustrated, October 14, 1974, E6. www.si.com/vault/1974/06/10/616133/the-tattletale-grays.

6. Lee Allen, The National League Story, New York: Hill & Wang, 1965 [revised edition], 3.

7. Albert G. Spalding, [revised and re-edited by Samm Coombs and Bob West], Base Ball, San Francisco: Halo Books, 1991, 116.

8. Dean A. Sullivan, ed., Early Innings: A Documentary History of Baseball, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1997, 66–7.

9. Spalding Official Base Ball Guide, Chicago: A.G. Spalding & Bros., 1883, 5.

10. Chicago Tribune, December 6, 1874, 2.

11. Spalding Official Base Ball Guide, Chicago: A.G. Spalding & Bros., 1883, 6.

12. National League Meetings, Minutes, Conferences & Financial Ledgers, BA MSS 55, National Baseball Library, 17.

13. Melville, Tom, Early Baseball and the Rise of the National League, Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2001, 79.

14. Spalding Official Base Ball Guide, Chicago: A.G. Spalding & Bros.,1886, 8–9.

15. National League Meetings, Minutes, Conferences & Financial Ledgers, 17.

16. This story is recounted in detail by Spalding in his book.

17. Neil W. MacDonald, The League That Lasted: 1876 and the Founding of the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs, Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. Inc., 2004, 45.

18. National League Meetings, Minutes, Conferences & Financial Ledgers, 17.

19. Macdonald, 67.

20. National League Meetings, Minutes, Conferences & Financial Ledgers, 15–16.

21. Tom Melville, “A League of His Own: William Hulbert and the Founding of the National League,” Chicago History, Fall 2000, 55.

22. Harold Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years, New York: Oxford University Press, 1960, 87.

23. Michael Haupert, The Entertainment Industry, Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing, 2006, 11–13.

24. MacDonald, 194.

25. MacDonald, 194–95.

26. Chicago Cubs records, Chicago Historical Society, Hulbert letter to Apollonio, Nov 22, 1876.

27. True to his word, the brief baseball career of Nicholas Apollonio ended before the year was out. He sold the Boston franchise to Arthur Soden, who would become famous as the originator of the reserve rule.

28. Chicago Tribune, December 10, 1876, 7.

29. J.E. Findling, “The Louisville Grays’ Scandal of 1877,” Journal of Sport History 3, no. 2, (1976), 184.

30. Findling, 186.

31. David Pietrusza, Major Leagues, Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 1991, 44.

32. Chicago Tribune, August 15, 1880, 12.

33. National League Meetings, Minutes, Conferences & Financial Ledgers, 132.

34. National League Meetings, Minutes, Conferences & Financial Ledgers, 132.

35. Lynn, London, Columbus, Pittsburgh, Guelph, Manchester, and Rochester were the seven who paid the steeper fee to contend for the championship.

36. Pietrusza, 49.