William T. Stecher: Ignominious Record Holder, Community Servant

This article was written by Jonathan Frankel

This article was published in The National Pastime: From Swampoodle to South Philly (Philadelphia, 2013)

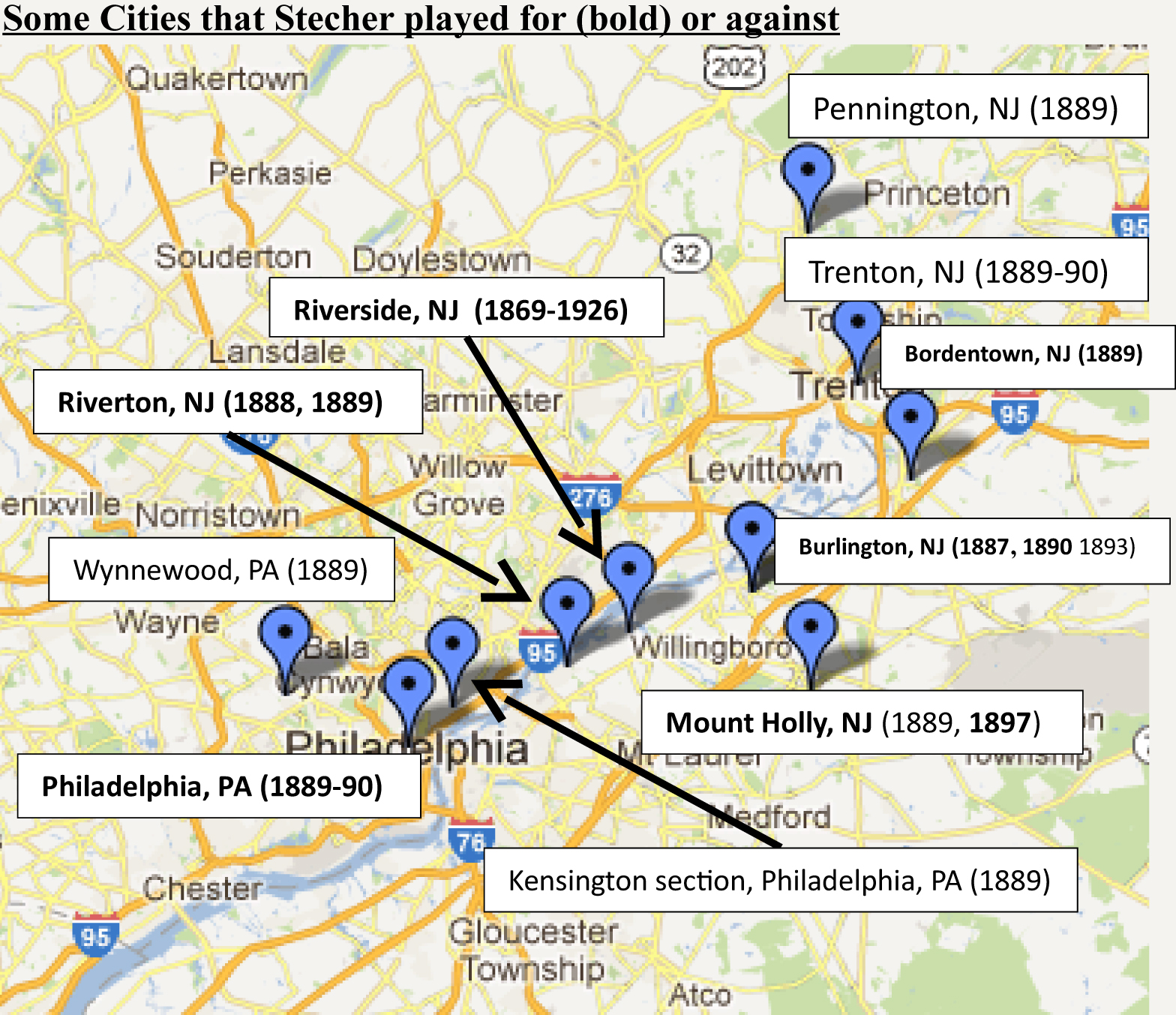

0-10, 10.32: That is the major-league career line for one William T. Stecher of Riverside, New Jersey.

If you look it up, the record book tells you that Stecher also holds the records for the “most career games by a pitcher who lost all his games (0–10)” and “most career innings by a pitcher with an ERA above 10.00 (68 innings, 10.32).” Not flattering records for any player to hold. But how did Stecher come about this line and these records in his single season in the majors with the 1890 American Association Athletics of Philadelphia? How did he get the opportunity to set the records? And what happened to Stecher after his brief moment in the sun?

Like many players, there is more to this man than his stat line. This article highlights Stecher’s baseball career and his post-career accomplishments, and introduces some of the amateur teams in the Philadelphia and New Jersey areas that Stecher played for and opposed.

William T. Stecher was born in Riverside, New Jersey on October 9, 1869, the fourth of four children of Rudolph and Paulina Stecher. Rudolph had originally come to the US in 1847 from the hot springs town of Baden-Baden and settled in Riverside in 1854. He was one of the organizers of the new township of Delran in 1880 and was to serve as poundkeeper, hotelkeeper, constable, and overseer of the poor (many simultaneously).

Stecher’s Amateur Base Ball Beginnings

There is little record of Stecher’s early years, but he was apparently a good enough athlete at age 17 that in 1887 he was pitching for the local Riverside amateur team, according to the August 7, 1887 Philadelphia Record . He was hit hard (10–1) in the only game that was found, against the Ontario team. His brother, Frank played in the game as well. William also played for the Burlington club later in the year.

In 1888, the Riverton club signed him in early May. In his first game, on May 5, he was opposed by Mike Kilroy, and the game was umpired by Kilroy’s more famous brother, Matt. The May 17, 1888 Philadelphia Record quoted Matt as saying that Stecher “was the most promising youngster he had ever seen.” He had mixed success with Riverton, winning his first game by a score of 20–8 in a six-inning affair versus Richmond, but also later losing to the Young America squad by a 10–2 score.

Stecher with Bordentown

Nineteen-year-old Stecher started the 1889 season with a local amateur team in Bordentown, New Jersey, known as B.A.A. (Bordentown Athletic Association).

He debuted on Saturday, April 20, Opening Day, against the Royal Smyrna club of Philadelphia. He allowed six runs in five innings, while striking out four and walking three, resulting in a 6–4 deficit. He was swapped with “Mickey” McLaughlin, who allowed only one run the rest of the way as the Bordentown club came back to win 9–7.

Stecher pitched in a number of other games for Bordentown:

- May 11: Won, 15–1, versus the Perseverance club of Philadelphia; struck out 11.

- May 16: Pitched the first three innings against the Middle States League Philadelphia Giants, allowing five runs. The game ended up going 15 innings, with McLaughlin swapping positions with Stecher again (Stecher going to center field), and pitched 12 shutout innings. The game lasted three hours!

- May 18: Beat the Rising Sun club of Philadelphia (formerly the “Wunders”), 7–1, allowing only three hits, and walking and striking out six.

- May 22: Played center field in a 9–1 walkover of “The Bristols.”

- May 25: Combined with McLaughlin on a 7–3 win over the Clark’s Pottery team of Trenton. The Clark team wore “bright new uniforms (of) blue trousers, striped shirts, and red hose.” Stecher struck out 12 during his stay on the mound.

- June 8: Combined again with McLaughlin to beat the Kensington club, 11–1.

- June 18: Lost to the Pennington club, 7–6. Pennington is “a village somewhere up in Mercer County.” Stecher struck out 10 in his first documented loss.

- June 22: Played center field in a 9–3 win over the Wynnewood club.

- June 27: Beat Mount Holly, 8–4, striking out nine.

- June 28: Beat Mount Holly again, this time in a 21–0 trouncing. Stecher allowed only four hits and had three of his own while striking out seven.

- July 1: Combined with Plummer (who started in at catcher) in a 14–7 thumping. Stecher rang up seven more strikeouts.

- July 9: Lost, 2-0, to the Cuban Giants of Trenton of the Middle States League.

Stecher’s unofficial record with Bordentown was 7–2 and he established a reputation of striking out large numbers while having some control issues.

Stecher with Harrisburg

Stecher signed with the Middle States League Harrisburg Ponies in mid-February of 1889, but did not start the season with them. His strong amateur showing with Bordentown apparently convinced the Harrisburg club to give Stecher a try. Stecher made his first pro appearance on July 16, 1889, at Norristown. It resulted in a 4–2 win in which he allowed nine hits and three walks in nine innings while striking out five.

He subsequently won a convincing 13–1 game versus York on July 25, recording nine strikeouts. The Harrisburg Patriot noted, “His curves, ups, downs, ins and outs, are very effective.” York returned the favor four days later, knocking him out after five in a 10–4 loss. After two more wins versus Shenandoah in early August, the highlight of Stecher’s baseball career occurred.

On August 9, 1889, he pitched a no-hitter versus the Cuban Giants, issuing five walks and striking out three. Hall of famer Frank Grant was in the lineup for the Giants that day. After the game, Stecher went home to spend time with his mother.

Stecher is found pitching for the Riverton amateur team later in August, beating Rising Sun and losing to Manayuk. Throughout Stecher’s 1889 Harrisburg campaign, he showed control problems—over six walks per nine innings—with occasional strikeout ability, including games of seven, seven, and nine strikeouts.

In 1890, Harrisburg became part of the Eastern Interstate League and Stecher remained on the team. In early April, he pitched in three exhibition games against major-league American Association teams from Rochester and Syracuse, giving him his first taste of that level of competition. After losing his first two games to Rochester, 7–3 and 3–0, Stecher won his final exhibition against Syracuse by a 12–3 score, scoring two runs himself. Once the regular season began, Stecher acquitted himself well, producing an 8–5 record. He continued to show flashes of his good curveball, resulting in games of seven, 10, and 13 strikeouts. But against the stronger competition of the EIL, he also showed his propensity for walks, perhaps due to the more advanced hitters’ ability to lay off his curves. His last game with Harrisburg was on June 26. Stecher is found pitching for Burlington against Bordentown on July 19 and August 10. Even though he was not dominating in the Eastern Interstate League, fortune was about to smile upon him as he had the opportunity to join a team in desperate need of any bodies that could play. Stecher happened to be in the right place when the American Association’s Athletics turned to him for help.

The Association Athletics in 1890

In 1890 there was a great deal of turmoil in baseball, with three major leagues: the existing National League and American Association, and the upstart Players League. This, no doubt, resulted in a great thinning of talent across the leagues, and hit the weak American Association especially hard. New franchises in Rochester, Syracuse, and Toledo replaced teams in Cincinnati (to the NL), Kansas City, and Baltimore. The 1889 Brooklyn Association team also joined the NL and was replaced with a new Brooklyn franchise. The Players League brought competition in eight cities, including Philadelphia (that team also was known as the Athletics). This gave the City of Brotherly Love three major-league teams competing for the crank’s quarter or fifty cents .

The Association Athletics started off fairly well, in spite of losing six regular games to the Player League Athletics. In fact, they led the league as late as July 17 with a 43–27 record. They had solid starters in third baseman Denny Lyons (OPS+ of 193), outfielder Curt Welch (OPS+ of 121), and pitcher Sadie McMahon (29–18). However, things began to fall apart and by the end of August, the team found itself in sixth place at 51–49 after an 8–22 interval.

At the end of August, Denny Lyons was suspended and subsequently sold to the St. Louis Browns, as he had been a nuisance in various ways to manager Bill Sharsig. His replacements—Henry Meyers (.158), Al Sauter (.098), and pitcher/infielder Ed Green (.117) among the main ones standing out near third base—created a huge black hole in order. At the same time, two of their pitchers were let go: Mickey Hughes was given his notice of release and Ed Seward asked to be “laid off” for the rest of the season due to his fatigued arm. This left the Athletics with only McMahon as a starter, and Stecher was one of the new pitchers brought in to fill the void.

In addition, a season-long shift continued at shortstop: Ben Conroy (.171) to start the season, followed by Harry Easterday (.147), Joe Kappel, and finally George Carman (.172).

By mid-September, catcher Wilbert Robinson, first baseman John O’Brien, left fielder Blondie Purcell, center fielder Curt Welch, and right fielder Orator Shafer were released due to the team’s financial shortcomings (they were broke!) and were replaced by a litany of no-names and amateurs, most hitting under .200. The newly reborn Baltimore Orioles were the main recipients of these castoffs, including McMahon.

All of these movements created the opportunity for Stecher and simultaneously doomed him. What follows is a game-by-game summary of his stay with the Athletics.

STECHER WITH PHILADELPHIA

GAME 0: SEPTEMBER 2, 1890—EXHIBITION

- Stecher’s first appearance for Philadelphia was in an exhibition game on September 2, versus the St. Louis Browns in Wilmington, Delaware. Stecher won this game, 3–2, allowing only five hits in an agreed upon eight-inning contest, according to the September 3, 1890 Philadelphia Record.

GAME 1: SEPTEMBER 6, 1890

- Matchup: Athletics vs. Louisville, Jefferson Street Grounds

- Score: 0–7

- Stecher’s Line: 8 innings, 10 hits, 7 runs, 5 earned runs, 5 walks, 4 strikeouts

- Game notes: In his official major-league debut, Stecher gave up four runs in the first two innings, but then “settled down,” scattering five hits with his curves, according to the September 7, 1890 Philadelphia Press. The curve was apparently the calling card that got Stecher to the Athletics. Unfortunately, it would not fool the American Association hitters. Stecher batted eighth in the lineup, as he would a great deal during his stay with Philadelphia. From the September 8, 1890 Philadelphia Public Ledger, came the classic words of every prospective player: “With a little more experience and judicious coaching, he will no doubt develop into a good twirler.” This was not to be.

GAME 2, SEPTEMBER 13, 1890 (GAME 2)

- Matchup: Athletics at Baltimore, Oriole Park II (SW corner of 29th & Greenmount)

- Score: 6–18

- Stecher’s Line: 7 innings, 13 hits, 18 runs, 8 walks, 4 strikeouts

- Game Notes: This game was called after seven innings due to darkness. Baltimore scored in each of the seven frames, including a seven spot in the seventh for good measure. Stecher’s control issues continued with eight more walks. According to the account in the Philadelphia Public Ledger, “The way they punish his curves was a caution.” This leads one to wonder if he should not have bothered with his curve at all. The 1890 Baltimore Orioles entry had only recently joined the AA, rejoining the league on August 27 to replace the Brooklyn franchise. Prior to this, the Orioles had a team in the Atlantic Association and ran away with that league’s pennant. A good number of the Atlantic Orioles continued on with the Association Orioles. Baltimore was one of three teams to exist in two leagues (one major league) in the same season, the others being the 1884 Virginia franchise (Eastern League/ American Association) and the 1891 Milwaukee franchise (Western Association/American Association).

GAME 3: SEPTEMBER 20, 1890 (GAME 2)

- Matchup: Athletics at Louisville, Eclipse Park I (Elliot Park)

- Score: 0–10

- Stecher’s Line: 8 innings, 15 hits, 10 runs, 3 walks, 1 strikeout

- Game Notes: Louisville was in the midst of their only championship season in major-league ball (AA and NL), sporting an 88–44 record and taking it to the Athletics in the doubleheader on the 20th. To go with the second game woes, Louisville also pasted pitcher Green in a 22–4 beating in game one. Only two of the “original” Athletics went West on the road trip, and each player that did go had to sign an agreement to play for $5 per game and expenses, according to the September 18, 1890 Philadelphia Evening Bulletin.

GAME 4: SEPTEMBER 21, 1890 (GAME 2)

- Matchup: Athletics at Louisville, Eclipse Park I (Elliot Park)

- Score: 3–16

- Stecher’s Line: 7 innings, 15 hits, 16 runs, 10 walks, 2 strikeouts

- Game Notes: Stecher was brought back a day later to take more abuse at the hands of the powerful Colonels. This resulted in another late-inning pounding, as he allowed six runs in the seventh and final inning before the game was called due to darkness.

GAME 5: SEPTEMBER 26, 1890

- Matchup: Athletics at St. Louis, Sportsman’s Park I (Grand Avenue & St. Louis Avenue)

- Score: 3–7

- Stecher’s Line: 5 innings, 10 hits, 7 runs, 5 walks, 0 strikeouts

- Game Notes: This game and the next were two of Stecher’s “closer” games, but again, a combination of not enough run support and poor pitching led to a shortened game loss. The game was mercifully ended after five innings so that the Athletics could catch a train for Toledo.

GAME 6: SEPTEMBER 28, 1890 (GAME 1)

- Matchup: Athletics at Toledo, Speranza Park

- Score: 9–11

- Stecher’s Line: 4 innings, 6 hits, 7 runs, 6 earned runs, 6 walks, and 3 strikeouts

- Game Notes: Stecher lasted only four innings in game one of the doubleheader at Toledo. This was his closest final score, though it was 7–3 when he departed after four innings. Stecher swapped positions with third baseman Green in the fifth inning.

GAME 7: SEPTEMBER 28, 1890 (GAME 2)

- Matchup: Athletics at Toledo, Speranza Park

- Score: 1–15

- Stecher’s Line: 7 innings, 14 hits, 15 runs, 6 earned runs, 6 walks, 0 strikeouts

- Game Notes: With a thin pitching staff, manager Sharsig brought Stecher back for game two, with worse results than game one as Stecher got pounded for 15 runs as a result of 14 hits, six walks, and five team errors in this seven-inning affair.

GAME 8: OCTOBER 1, 1890 (GAME 2)

- Matchup: Athletics at Columbus, Recreation Park II

- Score: 0–14

- Stecher’s Line: 9 innings, 14 hits, 14 runs, 12 earned runs, 7 walks, 2 strikeouts

- Game Notes: Another stinker for Stecher, with seven walks, although he did hit a triple in three atbats. He allowed 10 of the runs in the last four innings. Coincidentally, this ball field would host the first home football game of The Ohio State University less than a month later, a 64–0 loss to Wooster on November 1.

GAME 9: OCTOBER 4, 1890 (GAME 2)

- Matchup: Athletics at Syracuse, Star Park II

- Score: 1–6

- Stecher’s Line: 5 innings, 7 hits, 6 runs, 6 earned runs, 3 walks, 0 strikeouts

- Game Notes: Three runs in the first inning by the Stars put this one away as the Athletics continued their non-support of Stecher, scoring just two runs scored in three games. Fewer than 100 people showed up for this dreary doubleheader (Philly won the first game 8–7), that was mercifully called after five innings due to rain and darkness.

GAME 10: OCTOBER 9, 1890

- Matchup: Athletics vs. Rochester, Jefferson Street Grounds

- Score: 4–10

- Stecher’s Line: 8 innings, 7 hits, 10 runs, 7 walks, 2 strikeouts

- Game Notes: Stecher finished out his major-league career with his sixth game of 10 runs or more allowed, although five Athletic errors did not help him. According to the Public Ledger, he “was not hit hard, but was wild in his delivery.” Rochester scored five in the second to take a 5–2 lead, then added three runs in the seventh and two in the eighth.

In the end, Stecher lost all 10 games he pitched, allowing 111 hits, 110 runs, and 60 walks while striking out only 18. He had a grand total of 27 runs of support during his stay (2.7 runs per game). To lend some perspective, the Athletics as a team lost their last 22 games and were 2–26 once Stecher officially joined the “rotation,” allowing 10 or more runs 17 times!

Back to the Amateur Ranks

Stecher went back to his hometown of Riverside in 1891, pitching for the local amateur team. He married Lizzie Kellock in July of that year, and they would go on to have three daughters. He pitched regularly for Riverside through 1894, mostly hitting leadoff and not having the success that he had enjoyed in his earlier amateur days. He was still striking out a lot of hitters, but he was still apparently infected from his Athletic days, as he lost of great deal of the games he started. His travels in the New Jersey amateur ranks took him to such towns and cities as Camden (where he also pitched in 1893 and 1895), Beverly, Media, Millville (Farmer Steelman batted against him), Salem, and even venturing as far as Hagerstown, Maryland. His responsibilities with the Riverside team seemingly exceeded just playing by this time, as there is a notice in the Philadelphia Inquirer in 1895 for the team looking for players with W. Stecher listed as the contact.

There is a Stecher that shows up as pitcher in 1897 for Mount Holly, although it does not explicitly identify him as William, it would make sense that it could be. While with Mount Holly, Stecher pitched against such local amateur teams as the Lehigh A.A., the Scholastic A.A., New Egypt, Germantown, and Burlington. It also appears that he may have pitched for Sunbury of the Central Pennsylvania League during the same time.

Stecher was back with the Riverside team in 1898 (he was only 28 at this point), while also serving as the town’s tax assessor.

Post Career: Businessman, Community Servant

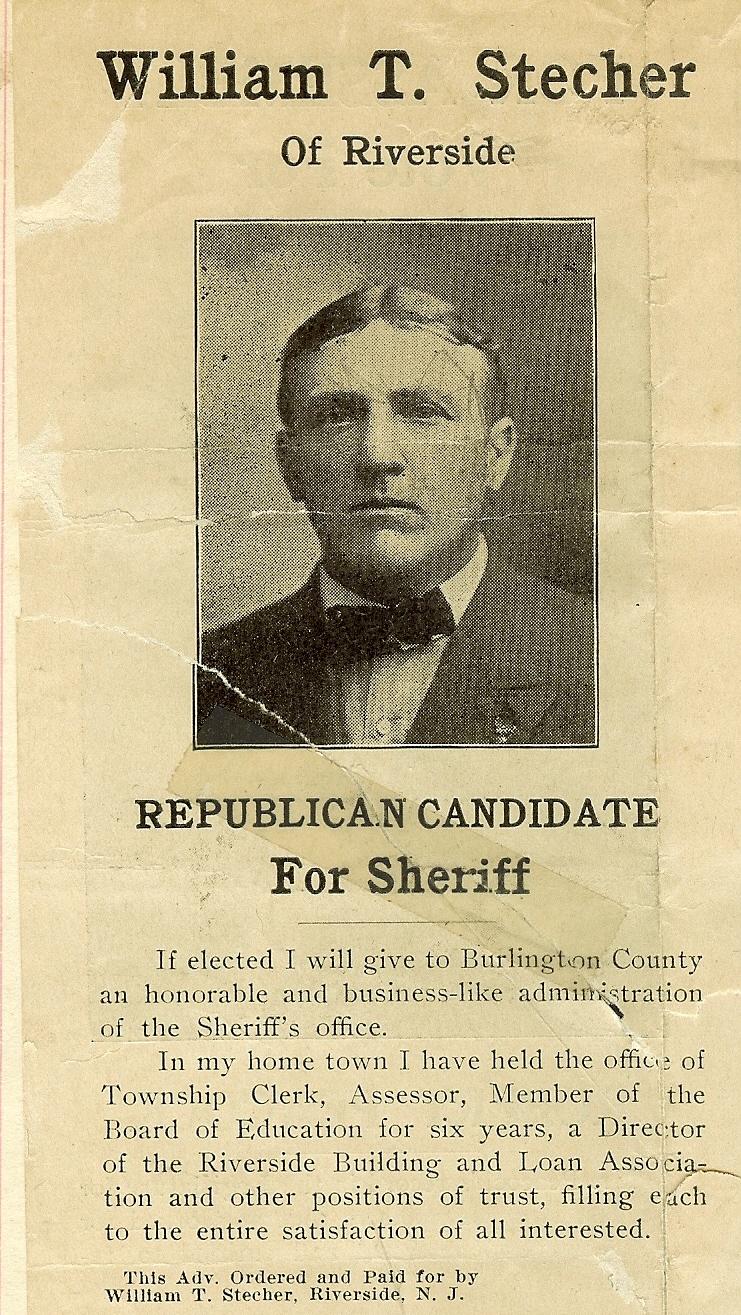

Toward the end of his playing days, like his father, Stecher became involved in the local community. He was Riverside’s tax assessor in the late 1890s, and was elected Sheriff of Burlington County (New Jersey) in 1914 after being defeated in 1908 and 1911. He ran a local cigar store and owned and ran several racehorses during this time. He also served as a committeeman, board of education member, director of the Riverside Building and Loan, and township clerk. In his later years, he had a successful real estate business in Riverside.

There is a Stecher road in current-day Riverside, though it is unknown whether this is connected to him, his father, or any of his family. But, based on his family’s strong local political and community roots, there is a good chance that it is associated with his family in some way.

On December 26, 1926, Stecher was killed at a train crossing in Riverside, failing to notice the oncoming train as he crossed in his auto. He was 57. The obituary heralded him as “one of the most popular officials that this (Burlington) county has had.” He was buried in his hometown Riverside Cemetery.

To most baseball fans, William T. Stecher is just a passing entry on Baseball-Reference.com or in a baseball encyclopedia—one who had an inglorious one-year career in which he set records for career futility. But how he got there and his post-baseball life tells a much more textured life of success and service.

JONATHAN FRANKEL, a SABR member since 1979, is a Quality Advisor at FedEx outside of Detroit. In 2010, he completed researching and compiling the missing batter strikeouts for the years 1897-1912, now part of Baseball-Reference.com. In 2012, he also discovered a “new” player, Joe Cross, during some American Association research. He has a blog about various baseball research interests, which he updates every once in awhile, at batterk.blogspot.com.

Author’s note

The game-by-game statistics provided here are from the ICI logs. While researching the games, I discovered several variances in individual statistics from each other as well as ICI, very typical of the era. One other note needs to be made regarding earned runs documented here and those in the “record.” Not all games have “official” earned runs. As Pete Palmer told me, “ICI did not have earned run data for all games, so what they did was take the percentage of runs earned in the games they had and applied it to the games they didn’t. They claimed that have at least 50 percent of the runs accounted for every team, but I am not sure they did. The 1969 Mac had the estimated ERA in italics, but this got lost in future editions.”

Acknowledgements

I wish to give special acknowledgement to Ed Morton for helping pull game accounts and digging other important information from non-Internet based sources. I would also like to thank Alice Smith, president of the Riverside Historical Society for her help.

Sources

Bordentown Register, Philadelphia Inquirer, Harrisburg Patriot, Philadelphia Press, Philadelphia Public Ledger, Sporting Life, and Seamheads.com article by Cliff Blau on the 1890 Athletics.