Willie Mays and the Giants: Why the Greatest Player Won Only Three Pennants

This article was written by David Kaiser

This article was published in Willie Mays: Five Tools (2023)

From 1954 through 1966, Willie Mays dominated the National League. While he won the MVP Award only twice, in 1954 and 1965, he led it in Wins Above Average (whose derivation I shall explain below) nine times, in 1954-58, 1962, and 1964-66, and finished among the leaders in all the other years in that span.

From 1962 through 1966, his teammates included four other Hall of Famers: Orlando Cepeda, Willie McCovey, Juan Marichal, and Gaylord Perry. Yet despite this extraordinary constellation of talent, the Giants won only two pennants, in 1954 and 1962. Essentially, they failed to take advantage of Willie and their other extraordinary assets because they balanced their superstars with a long list of dreadful players, dragging down the team’s won-lost record and losing two very close races to Dodgers teams whose top talent was far below theirs.

To show how this happened, I shall use the methodology I developed and explained at length in my book Baseball Greatness.1 Although Wins Above Replacement (WAR) has generally become the statistic of choice among sabermetricians, I used Wins Above Average (WAA) for two reasons. First, while the value of a replacement player is inevitably something of a guess, we can measure the value of an average player very accurately, making WAA a much more precise measurement.

Second, WAA makes it much easier to understand the value of any individual player to his team. A team of perfectly average players could be expected to win 77 games before expansion, or 81 games after it. A post-expansion team of average players and Willie Mays in one of his greatest seasons, in which he earned 8 WAA, could be expected to win 89 games, and another superstar (defined as 4 WAA or more per season) would get that team within pennant-winning range.

Unfortunately, a player with -3 WAA would negate a substantial portion of Mays’ value – and we shall find that the Giants’ lineup in many critical years included far too many such people. That, ultimately, is why he played in only three World Series, winning just one.

My calculations of WAA for position players like Mays use raw offensive data from baseball-reference.com, but they differ from that publication in two ways. First, I use Michael Humphreys’s fielding data, based on his Defensive Regression Analysis (DRA), in place of the methods used by baseball-reference because I am convinced that DRA is by far the most accurate historical fielding measurement.2 Second, for reasons explained in Baseball Greatness, I do not adjust players’ value up or down based upon the defensive position they played, which baseball-reference.com does for both WAR and WAA.

The Giants won their first pennant with Willie in his rookie year, 1951, and that team was an excellent example of a balanced pennant winner. Monte Irvin, with 6.1 WAA, was their only superstar, but Willie and Bobby Thomson added 2.9 WAA each, Alvin Dark and Eddie Stanky combined for an additional 4.8 WAA, and no Giants regular was below average. Altogether their lineup earned +13 WAA and their pitching staff +2, keeping them close enough to a Dodgers team with a superior lineup and slightly weaker pitching to tie them at 96 wins and win the three-game playoff.

After Mays missed nearly all of 1952 and 1953 while in the US Army, the Giants won the pennant in 1954 thanks largely to his greatest season, in which great hitting and fantastic fielding earned him an extraordinary total of 9 WAA. Only two of his teammates in the lineup, Monte Irvin and Hank Thompson, were above average, and the whole lineup without Mays was dead average. Giants pitching was outstanding, earning 11 WAA, and the Giants won 97 games. Then, a long drought began.

In 1955 Mays hit 51 home runs and finished the season with 7.1 WAA, but Hank Thompson was the only other above-average player in the lineup and Don Mueller, Alvin Dark, and Davey Williams had terrible seasons. The pitching staff also slumped badly and the Giants won just 80 games. In 1956 Mays led the league for the third consecutive year with 5.8 WAA, but rookie first baseman Bill White was the only other above-average player in the lineup. Dreadful performances by the aging Mueller and Dusty Rhodes and others left the lineup as a whole -13 WAA and the team went 67-87. Mays improved to 6.6 WAA in 1957 but White went into the Army and the Giants’ record improved by only two games in their last year in New York.

Things improved in San Francisco in 1958 when the Giants added Orlando Cepeda (2.1 WAA) and above-average outfielders Leon Wagner and Felipe Alou, but Mays’ remarkable 8.2 WAA – his second-best season to date – was three wins better than that of the team as a whole, which finished 80-74. In 1959 Mays, Cepeda, and rookie sensation Willie McCovey combined for 11.6 WAA, but the rest of the lineup was -2.6 WAA and the pitching barely above average, and the Giants won just 83 games. Mays, Cepeda, and McCovey remained the only above-average players in the lineup in 1960 with 10.2 WAA between them, while the pitching staff declined to below average and the team won 79 games.

The National League had now reached a generally mediocre level. The Giants actually had the best run differential in the league in 1961 and projected to win 91 games, but they missed that projection by four wins while the Reds exceeded their projected record by 10 wins and took the pennant.

The 1962 Giants finally found the right formula and emerged as the strongest team Willie Mays ever played on, winning 101 regular-season games and again defeating the Dodgers in a three-game playoff. Mays was the team’s only superstar, with a tremendous 7.3 WAA – his highest total since 1957 – but outfielder Felipe Alou (2.8 WAA), third baseman Jim Davenport (2.5), McCovey (1.9), and Cepeda (1.8) added 9 WAA between them, and the only below-average player in the lineup was shortstop Jose Pagan (-2.6 WAA.) A fine pitching staff added 6.1 WAA to the lineup’s 12.4.

The 1963 team, however, established the disastrous pattern of the next four years. They were one of only two National League teams since 1901 to include four superstar players with 4 WAA or more: Mays (7 WAA), Cepeda (4.4), McCovey (4.1), and pitcher Juan Marichal (5.2).3 The rest of the Giants’ pitchers were slightly above average, but the rest of the lineup included five infielders totaling -8.9 WAA. The lineup as a whole earned just 2 WAA, despite three superstars’ total of 15.5. The team won just 88 games and finished third.

In 1964 McCovey had a terrible season, falling below average, but Mays (a great 8.1 WAA) and Cepeda (2.5) were joined by a new find, third baseman Jim Ray Hart (an excellent 3.2 WAA.) Felipe Alou, however, had been traded, the infield was as bad as ever, and the whole line up earned -3.8 WAA. The pitching, led by Marichal, was outstanding, with 12.4 WAA, but the team finished fourth with 90 wins.

The Giants in 1965 and 1966 lost very close pennant races to the Los Angeles Dodgers on the last weekend of the season – and the Dodgers provided a fascinating contrast to the chronically unbalanced Giants. The Dodgers (because of Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale) had a reputedly great pitching staff while the Giants, with Mays and McCovey, were known for their power. Sandy Koufax, however, was the only great pitcher on the Dodgers in that era, while the rest of the staff benefited from pitcher-friendly Dodger Stadium.4

The Giants staff, led by Marichal, was actually superior in 1965, earning 15.8 WAA to the Dodgers’ 6.5 And as for their lineups, while the Giants’ three best players – Mays (8.5 WAA thanks in part to 52 home runs), McCovey (3.1), and Hart (2.1) – earned 13.7 WAA among them, the Dodgers’ best three, shortstop Maury Wills (2.5), second baseman Jim Lefebvre (2.4), and left fielder Lou Johnson (1.6), totaled 6.5. Catcher John Roseboro (-1.9 WAA) was, however, the only below-average player in the Dodgers lineup, while the Giants lineup included Matty Alou (-2.2), Davenport (-2.5), Dick Schofield (-2.6), and Hal Lanier (-3.7). Overall, the Giants lineup earned -5.8 WAA despite Mays, McCovey, and Hart, while the Dodgers lineup earned 4.8. LA won the World Series that year against the Minnesota Twins.

In 1966 Mays (who led the National League for the last time with 7.7 WAA), McCovey (4.8), and Hart (3.7) were the only above-average players in the Giants lineup, whose outfield now featured Jesus Alou (-2.8), Ollie Brown (-1.8), and Cap Peterson (-1.4), along with the usual dreadful infielders. Lefebvre and first baseman Wes Parker led the Dodgers lineup with 3.4 and 3.2 WAA, and the lineup as a whole finished with 4 WAA to the Giants’ 2. The Dodgers pitching staff also improved to 10.5 WAA while the Giants’ declined to just 3.1. The Giants were very lucky to finish just two games behind.

The two Willies performed at a superstar level in 1967-8, but the rest of the team remained too weak to challenge the St. Louis Cardinals in those years. Mays finally fell below the superstar level in 1969, but he regained that level for the last time at age 40 in 1971 with 4.8 WAA, when the Giants won the NL Western Division championship with just 90 wins. They lost the LCS in four games to the Pirates.

Led by their owner, Horace Stoneham, the Giants seemed to believe that just about anyone could fill in the rest of the lineup as long as they had a few big stars. Writing Baseball Greatness, I discovered that other clubs have shown the unfortunate tendency to believe that with two great players in the lineup, they need not worry too much about other positions. The New York Giants in the late 1920s and early 1930s had three of the greatest players in the National League, Mel Ott, Bill Terry, and Carl Hubbell, yet won only one pennant because of a terrible supporting cast.

Between 2008 and 2013, I found three AL Eastern Division rivals – the Yankees, Red Sox, and Rays – that competed on pretty equal terms, with the Yankees averaging 94 wins, the Rays 92, and the Red Sox 89. During that period, Red Sox players posted 13 superstar seasons, the Yankees six, and the Rays only four. The Rays, however, almost never had a below-average player in their lineup, while the two richer clubs had many.

There’s no substitute for having Willie Mays or his contemporary counterpart Mike Trout on your club, but it’s a lot easier to improve your club by finding an average player to replace a man earning -3 WAA a year than it is to find the new Willie Mays. Sadly, the Giants failed that test for much of his career.

DAVID KAISER first experienced Willie Mays on television during the 1954 World Series, at the age of 7, when he saw Willie’s famous catch in the first game. A historian, he taught for 37 years at Harvard, Carnegie Mellon, the Naval War College, and Williams College. He is the author of two baseball books, “Epic Season, The 1948 American League Pennant Race” and “Baseball Greatness: The Best Players and Teams According to Wins Above Average.” He has given numerous presentations at local SABR chapters and at a number of national conventions. He lives with his wife, Patti Cassidy, in Watertown, Massachusetts.

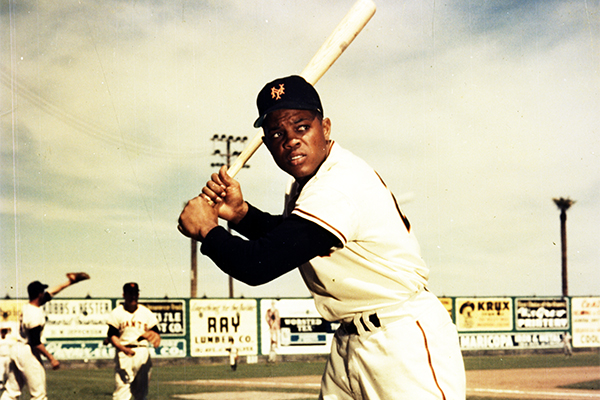

PHOTO CREDIT

Willie Mays during spring training in 1952, SABR-Rucker Archive.

NOTES

1 David Kaiser, Baseball Greatness: Top Players and Teams According to Wins Above Average, 1901-2017 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2018), esp. pp. 1-22.

2 See Michael Humphreys, Wizardry: Baseball’s All-Time Greatest Fielders Revealed (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

3 The other such National League team was the 1972 Reds, with Johnny Bench, Pete Rose, Joe Morgan, and Tony Perez. Five American League teams have accomplished this feat.

4 Don Drysdale’s great seasons were behind him by 1965. He was average in 1965-66 and only 1-2 WAA above average in 1967-68.

5 This was partly because Dodgers fielding was very good, while Giants fielding was dreadful.