Willie Mays Returns to New York

This article was written by Rob Garratt

This article was published in Willie Mays: Five Tools (2023)

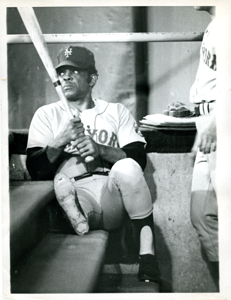

Willie Mays’ skills had diminished by the time the New York Mets traded for him in May 1972. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

After almost 20 years as a Giant, Willie Mays was traded from San Francisco to the New York Mets in May 1972. It was a shock to the baseball world, since Horace Stoneham, old-fashioned owner of the Giants, had said on numerous occasions that he would never trade Mays, that Mays was both the face and the heart of the Giants franchise, and that the Giants boss regarded Mays almost as family.

His affection for the Giants superstar went back to the spring of 1951, when Stoneham brought Mays up to the New York Giants from Triple-A Minneapolis; it remained strong during all of Mays’ years as a Giant, both in New York and San Francisco. Stoneham was adamant that he wanted Mays to finish his career in baseball as a San Francisco Giant. But in the spring of 1972, Stoneham’s finances were such that he let Mays go, trading him to the New York Mets.

A closer look at the history of the Mays trade reveals a different timetable. Stoneham’s financial difficulties actually took root five years earlier despite his remarks to the contrary. In the spring of 1967, Charles O. Finley, the maverick owner of the Kansas City Athletics, persuaded his American League fellow owners that the Bay Area was a great place to put an American League club to share the riches that the Giants had been raking in since their move in 1958 from New York City to San Francisco.1 So, at the end of the ’67 season, Finley packed up his team and moved west, to Oakland. The Oakland A’s began the 1968 season nine miles across the bridge from San Francisco.

Finley’s move dealt a severe blow to Stoneham’s finances and signaled the beginning of the end for his time as Giants owner. Sensing the restrictions that the Athletics would put on his potential revenue, the Giants boss was outspoken about sharing the Bay Area market. While others in baseball praised the move and thought of it as growth for baseball, Stoneham was uncharacteristically blunt in his opposition. “Certainly the move will hurt us,” he said. “It is simply a question of how much and if both of us can survive. I don’t think the area at the present time will take care of both of us as much as [the Athletics] think it will.”2

Stoneham was prescient. After only one season, the pattern was clear: the A’s cut the Giants attendance in half, with huge consequences for the remainder of Stoneham’s ownership, the end of the 1975 season. Baseball’s days of television contracts, merchandising, and playoff revenue-sharing lay in the future; in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the gate was still the primary source of income for ballclubs.

Once the A’s came to Oakland, the Giants saw a huge drop-off in their gate receipts; attendance fell to about half of what they were drawing in the early 1960s. The interesting thing about the A’s coming to the Bay Area was the regularity of the attendance figures. A new American League franchise in the Bay Area did not attract or generate more fans. Rather, it split the existing yearly totals of fans coming to baseball games. Through the 1960s the Giants had been drawing consistently about 1.5 million every year. From 1968 on (with the arrival of the A’s), both teams essentially split the annual draw the Giants had maintained earlier in the decade.3 This result was rather surprising, given the great baseball Oakland was playing in the early 1970s, winning three consecutive World Series from 1972 through 1974.

This loss of annual revenue hurt the Giants’ ability to put a competitive team onto the field and dictated that Stoneham would have to limit his expenses, greatly affecting the success his teams would have in the standings. One way to reduce costs was to sign younger, less expensive ballplayers; the other was to jettison the established, and better players, those with high-end contracts. Stoneham was forced to do both, a painful necessity for a player-friendly owner.

By the end of 1973, most all were gone, those players who contributed to the glory years of the 1960s. Orlando Cepeda was dealt in 1966 to the St. Louis Cardinals, before the fiscal difficulties were apparent. Cy Young winner Mike McCormick was traded to the Baltimore Orioles in 1970; Gaylord Perry was dealt to Cleveland before the 1972 season (where he was a Cy Young Award winner the next year). Shortstop Hal Lanier was sold to the Yankees in 1971 for cash and All-Star catcher Dick Dietz was claimed by the Dodgers off waivers in early 1972. Slugging third baseman Jim Ray Hart was sold to the Yankees in April 1973. Willie McCovey was sent to San Diego in the fall of 1973, and Juan Marichal was sold to the Boston Red Sox that December.4

But no one trade or player sale brought with it the agony Stoneham felt when he realized he would have to part with Willie Mays. In 1971 Mays turned 40 and everyone knew that his best playing days were behind him. Still, Stoneham had such deep affection for Mays that he wanted him to retire as a Giant – the only team he had played for in his entire 20-year career.

The Giants’ finances, however, no longer resembled the profitable early years in San Francisco, due primarily to the arrival of the A’s; simply put, Stoneham was running out of money. The blunt reality came off the bottom line: The Giants could not afford to keep Mays, at least in the manner that Stoneham intended. Once the two-year salary was cobbled together for his star center fielder – $165,000 for the 1972 and 1973 seasons – Stoneham knew he would have to find Mays a new home, a place where he would be happy, where he could be guaranteed this two-year salary (something the Giants could not do), and where his future might be secure, possibly as a coach or even a manager. With his ballclub’s revenue fading fast, Stoneham put all of his efforts into getting Mays settled. The Giants boss decided to look in the one obvious place for Mays’ comfort and well-being.

In the spring of 1972, Stoneham entered into secret negotiations with Mets owner Joan Whitney Payson, and chairman of the board M. Donald Grant to trade Mays to the New York team. They were the only club Stoneham contacted because, in a clearly nostalgic move, he felt that Mays should be back where he began his career, had so many wonderful years and was a legend, still, in the city. A crucial part of the trade details for Stoneham involved assurances from Payson and Grant that Mays would be given some kind of extended contract with the ballclub once his playing days were over.

As is the case with an old-fashioned and well-intended player-first owner, Stoneham felt the need for secrecy in the event the deal with the Mets fell through and that Mays’ pride would be hurt, the result of feeling discard by a cash-poor owner.5 The attempts at secrecy failed, however, as newspapers on both coasts caught wind of the story. Immediately, columnists in San Francisco and New York began speculating about the results. A surprised and somewhat annoyed Mays learned third-hand about the trade when the Giants were visiting Montreal in early May, wondering why the organization for which he had played his entire career would not inform him of such a possibility, and maybe even involve him in the talks. Briefly, he thought about retiring from the game.6

On May 11, 1972, the finalized negotiations became official news. Willie Mays was traded to the Mets for a minor-league pitcher named Charlie Williams; there was also a hint of an additional unspecified amount of cash from the Mets, rumored to be between $50,000 and $200,000.7 In a gesture that conveyed the highest form of respect (and an attempt to mollify the player), Stoneham brought Mays in on the final hours of deliberation with Payson and Grant and then ushered him in to the hastily organized press conference at the Mayfair Hotel announcing the trade.8

In his remarks, the Giants owner tried to put on a brave face for the situation but could hardly hide his disappointment, nor conceal his dire economic circumstances. “I never thought I would trade Willie, but with two teams in the Bay Area, our financial situation is such that we cannot afford to keep Willie and his big salary as well as the Mets can.”9 Grant followed with some perfunctory remarks, saying that the Mets planned to keep Mays around for a long time, securing his future in baseball. The player himself spoke briefly, and diplomatically, saying that he was happy to be back in New York, was looking forward to playing for the Mets, and that he was grateful to Stoneham and the Giants for all that they had given him.10 The press conference ended and with it one of the most fabled chapters in Giants history.

In a bizarre twist, Mays’ start in a Mets uniform would be against his former team, which traveled to New York after its series with Montreal. As if to underscore his legendary status in Gotham, Mays homered to break a 4-4 tie, leading his new team to a 5-4 victory. During the Mets series in New York, Stoneham, who had stayed on in New York after the press conference, asked to see Mays after one of the games. The two stayed up late into the night in the owner’s hotel suite, Stoneham drinking and talking emotionally and regretfully about the trade, and Mays quietly listening. Looking back on that night more than 40 years later, Mays reflected on Stoneham’s genuine concern “for my welfare, not only for my salary but that I would be taken care of in the future. I realized then how much he cared for me and how hard the trade was for him to make.”11

The press’s reaction to Mays’ return to New York reflected the changing tides of two cities’ connections to their baseball teams. In New York, Mays was treated as an Odyssean hero, finally home after years of wandering exile. “WILLIE COMES HOME” read one East Coast headline for the Alabama-born ballplayer’s trade to the Mets.12 Much of this welcome was for the player himself, his prominence, and his reputation as the greatest player of his generation.

Nor did his age bother some writers. Dick Young of the New York Daily News wrote that even a 40-year-old Mays was better than many players in the game.13 But others saw in Mays’ return a chance to rewind the clock and bask in nostalgia. New York Times columnist Red Smith reminded his readers of a young Mays, roaming the outfield at the Polo Grounds during the golden age of New York center fielders: DiMaggio, Snider, Mantle, and Mays.14

In another article, headlined “Moments to Remember,” Arthur Daley interpreted Mays’ return as cathartic, healing the old wounds left by the painful memories of the Giants leaving New York after the 1957 season, taking with them the young superstar who had dazzled Polo Grounds fans with his amazing exploits. Daley reverently recited the famous New York moments in Mays’ career, including the “impossible” throw to nail the Dodgers’ Billy Cox at home during the 1951 pennant race and the astounding catch of Vic Wertz’s fly ball in the 1954 World Series.15

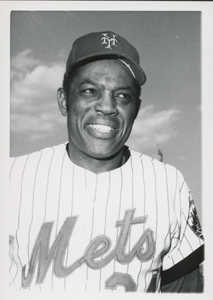

Financial difficulties forced Giants owner Horace Stoneham to trade Willie Mays. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

On the other coast, reporting of the Mays trade also revealed an emotional edge, but unlike New York’s in every respect. The tone was negative, and pointedly critical toward the Giants and Stoneham. Bucky Walters of the San Francisco Examiner wrote that it was too little, too late. With a rebuke for Stoneham and the front office, Walters complained that instead of the no-name rookie pitcher Charlie Williams, “it would have been possible for the Giants to have gotten several established players for Mays a couple of years back when his market value was still high.”16

Other San Francisco sports journalists joined in with the criticism. Most took note of Mays’ reduced productivity and took it as a sign of decline in quality. And his departure was one more example of the good old days that are gone forever. The commentary was less concerned about losing Mays and more about the sagging state of Giants baseball.

A few hundred miles to the south of San Francisco, Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times used the Mays trade to sling a few barbs north. Picking up on the rumor that there was some cash involved in the Mays trade, Murray scolded Stoneham for selling one of baseball’s gods for “30 pieces of silver,” and, using the Mays trade as a ruse, the writer shifted his target to the city he loved to hate.

San Francisco has an abhorrence of strangers and Willie was a 14-year stranger – in San Francisco but not OF it – and the townspeople kept looking at each other with a “Who invited him?” look. San Francisco frowns on enthusiasm, anyway, preferring a bored acceptance. It is not a town, it’s a cocktail party. Willie must have felt like a guy who showed up wearing brown shoes with his tux.”17

Murray’s snide allusion to Stoneham’s betrayal of Mays for a handful of silver set off others in the press, some of whom castigated the Giants owner for his plantation boss’s attitude (a gross inversion of Stoneham’s actual concern for and connection to his players), especially the ones with whom Stoneham had developed long-term relationships, like Mays. Initially, an emotional Stoneham didn’t respond to criticism, preferring instead a difficult – and what must have been an especially painful – silence. Years later, however, he corrected the record in an interview with Mays biographer Charles Einstein. When Einstein got around to asking Stoneham exactly how much money he actually got in the Mays trade, the answer was surprising.

[Stoneham] said, “There was no money.”

“None?”

“None. Do you think I was going to give him up for money?”

The only element involving money, Stoneham said, was what the Mets pay Mays over the next few years that Stoneham couldn’t.18

For the two principal actors in the Mays trade, things wound down rather quickly, so that both would be out of baseball in the next few years. After the trade, things hardly improved for Stoneham. His teams finished well off the pace in the post-Mays years, and he lost at the gate as well. In 1974 and 1975, the Giants’ home attendance was the lowest of any season since the team moved west, barely clearing the 500,000 mark for each year. There were some games in 1974 and 1975 when the attendance was below 1,000.

Indeed, the Giants’ attendance was so low in those years that it prompted San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen to write, “[T]he Giants’ ‘Fan Appreciation Day’ is coming up soon and I can’t wait to see what Horace Stoneham gives him.”19 As a result the Giants’ financial situation was dire.

In the spring of 1975, Stoneham approached his fellow National League owners with grim news; he had enough money to meet only two months of payroll and would need a loan to finish the season. At the same time, he announced his intention to sell the team, hoping to find a local buyer to keep the Giants in San Francisco. After some complicated and dramatic turn of events, Stoneham did just that; he sold the ballclub to San Franciscan Bob Lurie in February of 1976 and, after more than 50 years in baseball, retired to Scottsdale, Arizona.

The trajectory for Mays was a bit different and slightly longer. Initially, he enjoyed some real success as a New York Met, although he was no longer an everyday player. Nonetheless, his presence on the Mets roster and the likelihood that he would play energized New York City fandom. As it turned out, by midseason the 1972 Mets were beset with crucial injuries and Mays had to be called upon to play more than he wanted or could with full energy.

But he still drew plenty of fans, both at home and on the road. One memorable away game was his return to Candlestick Park on July 21, where he dressed for the first time in the visitors clubhouse. At every at-bat, he received a standing ovation from the home crowd and the fans were particularly roused when he hit a two-run homer in the fifth inning. The Mets finished third in 1972 and Mays’ first season as a Met was substandard for him – 69 games played, a .267 batting average, but with a .402 on-base percentage that led the team and a .466 slugging percentage that was second on the team.

The real measure of his success, however, came from the steady adulation of New York baseball fans, who were delighted to have a living legend back in their midst, even if their hero was in the sunset of his playing days. One writer claimed that Mays’ return rejuvenated a troubled city. “Willie Mays is reminding New York of our best moments. … The city is an unhappy land that needs a hero, but we are less unhappy now that Willie Mays is back where he belongs.”20

After the 1972 season, things turned a little sour for Mays in New York. He had had some difficulties with Mets manager Yogi Berra over his playing time and his role as a leader in the clubhouse. He wanted his time in the lineup to be parceled out to include rest days, so he could maximize his energy in the field and at the plate. Berra wanted to control when Mays would play and how much (usually more than Mays wanted).

The younger players looked up to Mays but also could sense his frustrations over declining abilities. Nonetheless, they saw him as a true leader. Tom Seaver recalled that Mays approached him before a game to find out how he would pitch to everyone in the opposing lineup in order that Mays could position himself in the outfield. Seaver was quoted as saying that no other position player had ever asked him how he was going to pitch to hitters: “Nobody ever did that to me … Nobody.”21

During the winter of 1972-73, Mays sensed that his playing days were coming to an end. He made up his mind that 1973 would be his last year.22 Injuries were mounting and it became obvious, especially to him, that he could no longer perform even at the level of his last few years in San Francisco. By midseason in 1973, playing sparsely, he was hitting .214. On more than one occasion in the outfield, he dropped a fly ball, or had to underhand a toss to another outfielder to get the ball back into the infield. It was painful for everyone to see, all the more because of who it was in the field or at the plate.

Fans may have recognized it, but for the most part overlooked it, in admiration of the legend behind the man. But the sportswriters saw it, and, with a certain amount of anguish and pathos, began to reflect on Mays’ changes in their columns. In what was the characteristic tenor of the New York writers, Roger Angell wrote, “His failings now are so cruel that I am relieved when he is not in the lineup. It is hard for rest of us to fall apart quite on our own; heroes should depart.”23

The San Francisco columnist Wells Twombley thought Mays’ decision to keep playing was tragic.24 Players, however, were more sympathetic, even though they were aware of the diminishing powers. Teammate Tug McGraw saw the anguish in Mays’ situation. “Willie was forty-two and was hurt a lot. … [H]e wanted to help the club and also not embarrass himself. Sometimes he forced himself to play, and then he’d hurt himself again while trying to do it.” Tom Seaver remarked that they were going to have to tear the uniform off him, “It is sad to see, but it’s a beautiful thing too, because of the love he had for what he had done for some twenty-odd years.”25

In early August of 1973, the Mets announced plans for a Willie Mays Night to be held at Shea Stadium on September 25. That event signaled that 1973 would be Mays’ last year (even though he had not officially announced retirement, rumors circulated) and the National League began saying goodbye during the remainder of the season: Mays drew standing ovations on the road, playing for the last time in each city.

Then, with the season almost over, the official announcement came. On September 20, on the NBC Today show, Willie made it official by announcing the end of his playing career once the 1973 season was over. Later that afternoon at Shea Stadium’s Diamond Club, he held a press conference for the organization and spoke candidly about his feelings. “When you’re forty-two and hitting .211, it’s no fun. … I just feel that the people of America shouldn’t have to see a guy play who can’t produce.”26

A few days later, he was honored at the Willie Mays Night festivities, attended by former greats including Joe DiMaggio, Stan Musial, and Duke Snider, New York Mayor John Lindsay, local celebrities, and Willie’s family; the event was emceed by sports announcer Lindsey Nelson. A number of former Giants were in attendance as well, including Bobby Thomson, a 1951 teammate. Gifts poured in from various sources, including corporations, local stores, and a number of individuals. There were coats, food items, plaques, even an honorary degree from Mills College. Mays and his wife received a his-and-her pair of Chrysler automobiles; Horace Stoneham sent a congratulatory card and a Mercedes-Benz car as a gift. The teetotaler Mays received a case of scotch and a case of champagne. In a strange twist that has never been fully explained, the Mets gave Mays nothing, not a card, nor a single gift.27

But Mays’ playing career did not end with the final regular game of the 1973 season. The Mets went on to win the National League pennant and faced the Oakland A’s in the World Series. The A’s won the Series in seven games and Mays played sparingly, appearing in three games, with two hits in seven at-bats and just one RBI; he committed one error.

Nonetheless, it was a fitting bookend for Mays in baseball. He broke into the National League in 1951 and played in a World Series his rookie year with the New York Giants; he was ending his playing career with a World Series appearance in 1973 with another New York team.

He remained a few more years with the Mets as a bench coach, but it was an uneasy fit for him. The adjustment to not playing, but nonetheless being at the ballpark every day took its toll, emotionally and psychologically. In the late fall of 1979, Mays accepted an offer from Bally Casino Resort to work in public relations, mainly playing golf and hosting dignitaries. The salary of $100,000 per year gave him much more financial security than the coaching position with the Mets. But the position with Bally, a gambling organization, did not sit well with baseball. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn took exception to Mays’ position, with its proximity and connection to organized betting, and suspended him from baseball. Mays complained but did not challenge Kuhn’s authority.28

Six years later, a new commissioner, Peter Ueberroth, reinstated Mays. By this time Mays was living in the Bay Area and it wasn’t long before the San Francisco Giants, with new owner Peter Magowan, offered him a lifetime contract to be the ballclub’s ambassador to the general public. It appears that you can go home again, which is what the Bay Area had become for the Giants star. In a gesture of supreme appreciation, the Giants and the city of San Francisco would underscore the tie that Mays had with the Bay Area by proclaiming the address of the Giants’ new ballpark as 24 Willie Mays Plaza.

The Mets honored Willie Mays on August 27, 2022, in ceremonies at Citi Field. Joan Whitney Payson was said to have promised Mays that he would be the last Mets player to wear uniform number 24. As Anthony DiComo wrote for MLB.com, “Acquiring Mays was important to Payson, who had built the Mets into the hollow space vacated by the Giants – the team for which Mays would always be best-known.”29 His son Michael Mays represented his father at the pregame ceremonies, which included 65 former Mets players and four former managers. Mets President Sandy Alderson said, “There has been a 50-year gap, if you will, between a promise made and a promise kept. We felt that on this occasion today, in light of all the players we had here, all the generations, that this was the time to keep that promise.”30

ROBERT F. GARRATT lives on Whidbey Island in Washington State with his wife, Sally. Rob is an emeritus professor of English and humanities at the University of Puget Sound, where he taught courses on modern British and Irish literature and international modernism. He grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area, an ardent fan of the San Francisco Giants. Upon his retirement from university teaching, he began researching the major leagues’ move in 1958 to San Francisco and Los Angeles. That initial research resulted in “Home Team: The Turbulent History of the San Francisco Giants” (University of Nebraska Press, 2017), a comprehensive history of the Giants as a Bay Area team. He followed his history of the San Francisco Giants with a biography of Charles A. Stoneham, who owned the New York Giants during the Jazz Age (forthcoming from Nebraska). Rob has been a member of the Society for American Baseball Research since 2007 and is a contributing author in a number of SABR publications including the BioProject and the team histories. He has also published in NINE, a journal on baseball and culture.

NOTES

1 Finley was keen on promotions, stunts, giveaways and entertainment exhibitions. He paraded around the ballpark before games with his mule named Charlie O. He advocated for zany uniforms, argued for colored baseballs at night games, promoted the designated-hitter rule and pushed, unsuccessfully, for a designated runner to be used with free substitutions. His reputation among fellow owners was poor; he was regarded as petulant, boorish, and bullheaded.

2 “Stoneham’s View: ‘Move Will Hurt Giants’,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 16, 1967: 47.

3 The A’s drew around 1 million during their great 1972-1974 World Series championship years, when the Giants fell off to just over 500,000. See baseball-reference.com for attendance figures.

4 The source for these transactions is baseball-reference.com.

5 Charles Einstein, Willie’s Times: Baseball’s Golden Age (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004), 329.

6 Willie Mays, interview with the author, October 29, 2014.

7 “Mays for Charlie Williams,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 12, 1972: 53.

8 Associated Press, “Willie Arrives in New York for Owners’ Meeting,” Los Angeles Times, May 11, 1972: G1.

9 Jack Lang, “Willie Warms Up for Second New York Run,” The Sporting News, May 20, 1972: 16.

10 James S. Hirsch, Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend (New York: Scribner, 2010), 508.

11 Willie Mays, interview with the author, October 29, 2014.

12 United Press International, “Giants Trade Willie Mays to Mets,” Boston Globe, May 11, 1972: 53.

13 Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” New York Daily News, May 14, 1972: 122.

14 Red Smith, “Strawberries in the Wintertime,” New York Times, May 12, 1972: 33.

15 Arthur Daley, “Moments to Remember,” New York Times, May 14, 1972: S2.

16 Quoted in Joe Eszterhas, “A Town Without Willie,” Newsday (Long Island, New York), June 11, 1972.

17 Jim Murray, “Willie Mays Didn’t Leave HIS Heart in San Francisco,” Los Angeles Times, May 16, 1972: E1.

18 Einstein, Willie’s Times, 331.

19 “Caen on the Cob,” San Francisco Chronicle, August 11, 1974: 107.

20 Jeff Greenfield, Sport, October 1972, quoted in Hirsch, Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend, 519.

21 Hirsch, Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend, 513.

22 Allen Barra, Mickey and Willie (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2013), 388-390.

23 Einstein, Willie’s Times, 334.

24 Wells Twombley, “Tragic Ego Trip of Willie Mays,” San Francisco Examiner, May 11, 1973.

25 Hirsch, Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend, 520.

26 “‘Maybe I’ll Cry Tomorrow,’ Says Mays,” New York Times, September 21, 1973: 27.

27 Alan Barra, Mickey and Willie, 392. One writer speculates that by the middle of 1973 Donald Grant and the Mets front office had soured on Mays and wanted him gone. An ailing Joan Whitney Payson, who favored Mays, had lost her authority in the ownership and could not advocate for Willie, even though she never lost her affection for him. See Hirsch, Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend, 520. Honors came from other sources as well. The San Francisco Giants hosted Mays on Willie Mays Day at the ballpark in celebration of his 80th birthday. Steve Kroner, “Willie Mays Celebrates 80th Birthday,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 8, 2011, sfgate.com; President Barack Obama awarded Mays the Presidential Medal of Freedom at the White House on November 24, 2016, www.nbcsports.com/bayarea/giants/willie-mays-receive-presidential-medal-freedom.

28 Had he done so, he might have pointed out to the commissioner that he had nothing to do with the gambling side of the casino and indeed was prohibited as an employee from betting. Moreover, owners like George Steinbrenner (Yankees) and the Galbraith family (Pirates) owned racehorses., but they faced no action from the Office of the Commissioner.

29 Anthony DiComo, “Mets Retire Willie Mays’ No. 24 During Old Timers’ Day,” MLB.com, August 27, 2022. https://www.mlb.com/news/mets-retire-willie-mays-no-24. Accessed December 21, 2022.

30 DiComo.