Willie Stargell’s Pivotal Season: 1971

This article was written by Blake Sherry

This article was published in The National Pastime: Steel City Stories (Pittsburgh, 2018)

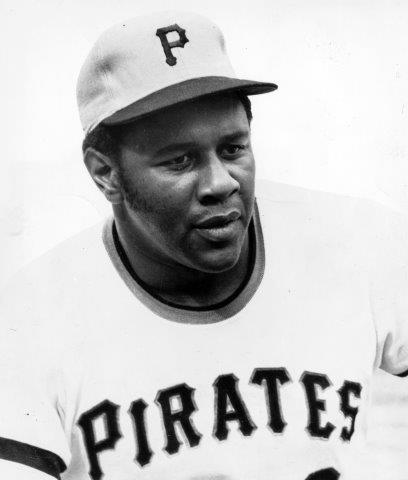

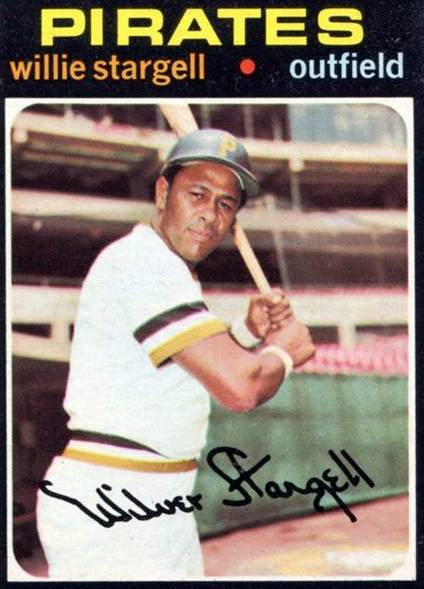

I wish that someone had told me when I was 15 years old that Willie Stargell was starting a five-year tear that would transform him from a good home run hitter to one of baseball’s superstars. If they had, I would have taken more mental snapshots of the man who was not yet “Pops.” While 1971 will always be remembered most for Roberto Clemente’s World Series heroics, it was also the year Stargell emerged from Clemente’s shadow and came into the national spotlight.

I wish that someone had told me when I was 15 years old that Willie Stargell was starting a five-year tear that would transform him from a good home run hitter to one of baseball’s superstars. If they had, I would have taken more mental snapshots of the man who was not yet “Pops.” While 1971 will always be remembered most for Roberto Clemente’s World Series heroics, it was also the year Stargell emerged from Clemente’s shadow and came into the national spotlight.

Stargell showed great promise as early as 1964, when he was named to his first All-Star Game. In 1965, he reached new highs with 27 homers and 107 RBIs. He demonstrated it was no fluke in 1966, hitting .315 with 33 homers, 102 RBIs, and a third consecutive All-Star selection. Two years later, in 1968, his average dipped to .237 with 24 homers. An eye injury resulting from crashing into the scoreboard in left field at Forbes Field may have been the cause. Later, Stargell said, “I don’t think I should have played after that accident,” which at times gave him double vision. “I probably would have been better sitting out the rest of the season.”1

He re-established himself with productive though not stellar seasons in 1969 and ’70. During the 1970 season, he began dealing with his daughter’s illness, diagnosed as sickle cell anemia. It became his cause to fight. He would set up a foundation to help those with the disease. After that season he participated in a trip with broadcaster Bob Prince to visit soldiers in Vietnam. It was life-changing. Seeing the horrors of war refined his definition of what a hero really was. It was no longer a man in a ball cap, but a person in fatigues serving his country for freedom.2

But with his 100-RBI seasons now four years removed, many felt that he had been a disappointment. Fans were still waiting for his breakout year. And now that he was 31 years old it seemed doubtful to happen. Later studies from experts like Bill James have indicated that players in their 30s tend to experience gradual production declines, not breakouts.3

Stargell showed up a different man for the 1971 season. He reported to training camp 20 pounds lighter than at the end of 1970. While part of that weight loss was due to his trip to hot, humid Vietnam, it also was the result of working harder on his fitness over the winter.4 This included long walks down a path, nearly four miles long, in a nearby graveyard.5 Arriving at camp in playing shape enabled Stargell to spend more time in the batting cage getting ready for the season rather than running in the outfield to shed the winter pounds.6

Stargell got off to a torrid start. He batted .347 in April, along with an .813 slugging average, a 1.211 OPS, 27 RBIs, and 11 home runs, breaking the previous April record of 10, shared by Tony Perez and Frank Robinson. The hot start yielded Stargell a Player of the Month Award. Yet despite his explosive month at the plate, the Pirates got off to a mediocre 12–10 start, including shutout losses in both games Stargell was out of the lineup with a virus.7

During that scorching April, Stargell, with his rocking and windmilling motion as he awaited the next pitch, had two three-homer games, both against the Braves. Three home runs in a game was not a new thing for Stargell. He first did it on June 24, 1965, in Los Angeles, then did it again on May 22, 1968, in Chicago.8

He cooled off a bit in May but was red-hot again in June, with an 1.193 OPS and 11 more homers, and the Pirates as a team began to follow his lead. They arrived at the All-Star break riding a six-game winning streak, leading the NL East by nine games over the Mets. Stargell was again named Player of the Month for June. He had 30 home runs and 87 RBIs while batting .320 going into the All-Star Game. The benefits of reporting to camp lighter seemed to be paying off. Manager Danny Murtaugh understood the hard work Stargell had endured in the offseason. “It is the kind of sacrifice that makes Stargell a champion,” Murtaugh said. “There’s no telling what he can accomplish now.”9 The manager was right. Stargell’s string of five consecutive Top-10 MVP finishes was just about to begin.

After the break, the Pirates won their first five, giving them an 11.5-game lead in the East. Stargell kept hitting. He hit two home runs in a game against the Giants on July 31 at Candlestick Park and then hit two more in the nightcap of a doubleheader the next day. At that point, Stargell already had 38 homers and 100 RBIs with two months to play. He was asked about Roger Maris and his record 61-homer season continually. But just as he’d been uninterested in celebrating his 11 home runs in April, he was uninterested in talking about Maris.10

Stargell, already a veteran of two knee surgeries, played much of that season with his left knee aching. Murtaugh was aware of the pain, and at one point he and the doctors suggested Stargell undergo immediate surgery to repair it, but he declined and pushed surgery to the offseason. As Stargell remembered in his autobiography, “There was no way I was going to miss the ’71 season. I knew that something very special was waiting for us just around the corner.”11

Nationally, Stargell and the Pirates were making headline news as well. Stargell was chosen for the cover of Sports Illustrated in August, and the article celebrated the Pirates melting pot of diverse ethnicity “in full active harmony at Three Rivers.”12 During this time, Stargell’s presence in the clubhouse continued to grow.

Murtaugh had a close and trusted relationship with the players. On top of that, Stargell explained, both Clemente and Bill Mazeroski were strong contributors to the team’s winning attitude. They’d both been in pennant races before and both led by example. But it “was Roberto that kept our competitive spirit finely tuned. He was a fierce competitor who wasn’t afraid to kick you in the behind if your performance slipped.” Stargell added, “Each one of us wanted to be like Roberto. He taught us to take pride in ourselves, our team and our profession.”13

While this was no doubt Clemente’s team, Stargell continued to emerge as a leader in his own way. He made it a point to keep everyone loose and keep the locker room inclusive. In his autobiography, he wrote that “a lot of us were pranksters, so my job wasn’t terribly difficult. But the players who needed my attention were not the veterans, but the rookies, who were often excluded from clubhouse pranks and camaraderie. I took it upon myself to make them feel a part of the team.” But he added, “Everyone needs a pat on the back occasionally, even veterans, and when they needed it, I gave it to them.”14

As Jim O’Brien, author of the “Pittsburgh Proud” series, put it, “If Clemente was the soul of the 1971 World Champion Pirates, then Stargell was its heart.”15 As the end of the decade neared, in 1979, Stargell was both the Pirates’ heart and its soul.

It was an eventful stretch run for the Bucs on many accounts. On August 14, Bob Gibson threw a no-hitter at Three Rivers Stadium, the first in Pittsburgh since 1907, with Stargell striking out looking for the final out. Though the Bucs trailed 11–0 in the ninth, I remember rooting for Stargell to hit one out and end the no-hitter. It was another moment I wish someone had told me to just appreciate history and savor witnessing a Hall of Fame pitcher tossing a gem like that. But instead, I left the park dejected as the Cardinals gained another game on the Pirates. The following day, despite another multi-homer game by Stargell, the Cardinals completed the four-game series sweep to close the Pirates’ lead to 4 games. The next night, Stargell’s four-hit, four-RBI performance against the Astros got the Pirates winning again.

Stargell had help along the way. Dock Ellis won 19 games. Clemente batted .341 in 132 games, All-Star catcher Manny Sanguillen batted .319, and Bob Robertson added 26 home runs. A young Al Oliver continued his solid hitting and center-field play as well. On August 23, Oliver had a monster game with a 6–4–5–5 line in the box score. He hit two home runs and a triple while helping the Pirates whip the Braves 15–4.

On September 1, in a game at Three Rivers Stadium that spawned a book published in 2006, The Team That Changed Baseball by Bruce Markusen, and a 2017 MLB Network documentary, The Forever Brothers, Stargell participated in history. He was the starting left fielder in the game in which Murtaugh sent out a lineup of all black and Latino players for the first time in major-league history. Stargell contributed a single, double, and sacrifice fly as the Pirates beat the Phillies 10–7.

A few days later, on September 6, Stargell hit his second grand slam of the season in a win over the Cubs. The first slam, hit on June 20, was in the second game of a doubleheader. In the opener, he’d blasted one into Three Rivers’ upper deck for only the third time in the stadium’s short history.16

However, during much of the second half, Stargell played through the pain of his aggravated knee, likely impacting his ability to hit 50 home runs for the season. It eventually forced him to miss five straight games starting September 15. Murtaugh wanted Stargell healthy for the postseason.

He came back in time to help the Bucs clinch the pennant on September 22. The 5–1 win put the pesky Cardinals away for the season. The next day, the Pirates put an exclamation point on it with Stargell’s two-run homer, pulling him even at 46 with Hank Aaron for the league lead. It supported Nellie Briles’ six-hit shutout.

When the regular season ended, Stargell sat atop the league in home runs, extra-base hits, and (the yet-to-be-invented) wins above replacement for non-pitchers with 48, 74, and 7.9 respectively. His home-run total edged Aaron’s by just one. He also had a .295 batting average and drove in 125 runs. While this performance helped the Pirates finish with the best record in the National League and win the East by seven games, Joe Torre of the Cardinals trumped him in winning the NL MVP with a stellar .363 batting average while driving in 137 runs, both league-leading marks.

Still, it added up to Stargell’s best season so far. He’d become a real superstar in the eyes of the baseball nation. But his turning-point season was not without frustration and disappointment. After his MVP-caliber year, he had a miserable NLCS, going 0-for-14 as the Pirates beat the Giants three games to one to head to the World Series against Baltimore. Stargell rebounded only slightly in the Fall Classic, batting .208. He also drew seven walks for a .387 on-base percentage. It was Clemente’s year to shine on the national stage. And as has been well documented, MVP Clemente dominated all aspects of the Series at age 37, with timely hits, a .414 batting average, and excellence in the field.

Still, it added up to Stargell’s best season so far. He’d become a real superstar in the eyes of the baseball nation. But his turning-point season was not without frustration and disappointment. After his MVP-caliber year, he had a miserable NLCS, going 0-for-14 as the Pirates beat the Giants three games to one to head to the World Series against Baltimore. Stargell rebounded only slightly in the Fall Classic, batting .208. He also drew seven walks for a .387 on-base percentage. It was Clemente’s year to shine on the national stage. And as has been well documented, MVP Clemente dominated all aspects of the Series at age 37, with timely hits, a .414 batting average, and excellence in the field.

Yet Stargell had one more growth spurt in his emergence as a leader. Throughout and after the World Series, he showed his teammates how to be about the team and not personal accomplishments. He was not one to sulk over his personal disappointments. After rain had delayed Game Two, Stargell calmly answered pointed questions from reporters about his lack of hitting in the NLCS and his 0-for-3 in Game One against the Orioles. He refused to snap at reporters. “When I was going good, I didn’t get excited, so when I’m going bad, I’m not going to hit the bottom of the barrel,” he said, “I’ll be able to say I did my best.”17 Wrote Kansas City writer Joe McGuff, “He never tried to hide from writers. He knew he was having a bad Series, but he always gave the impression that team winning was more important than any personal gains he could have in the Series.”18

Stargell was delighted to have scored the crucial second run in the 2-1 win in Game Seven. He led off the eighth with a groundball single and scored on Jose Pagan’s double to the left-center-field wall. “I must have looked like a runaway beer truck going around the bases,“ Stargell said. “It was a hit-and-run and I had to stop at second to make sure the center fielder wasn’t going to catch the ball. Once I got going again, though, I thought to myself, ‘There’s nothing that’s gonna stop me from making home plate.’” Then, with a Stargell smile, he added, “Of course, a guy with my wheels can afford to take chances. I stole 40 bases this year.”19 The center fielder bobbled the ball on his original throwing motion and Stargell—who really had stolen zero—slid home without a play.

The mature Stargell put his highly tuned skills and leadership to good use in 1972. It was another solid All-Star year for him. An injury limited him to only 138 games but he still batted a robust .293 with 33 home runs and was third in RBIs, driving in 112. He finished third in the MVP award voting.

In the offseason, tragedy was then thrust upon the Pirates. On New Year’s Eve, Clemente died in a plane crash shortly after takeoff as he tried to help get relief supplies to earthquake victims in Managua, Nicaragua. His body was never found. With the retirement of Mazeroski at the season’s end, and now the loss of Clemente, a void needed to be filled on the field and in the clubhouse. Leadership would fall to Stargell. Replacing Clemente as the team leader was not a role he actively went searching for, but he was ready.

When spring training 1973 opened for the mourning Pirates, Stargell in particular was barraged with questions about who would fill Clemente’s shoes as the team leader. Stargell grew weary of the question, but stayed on the high road, claiming he was not seeking to replace Clemente, no one could, but as the elder statesman of the team, he’d help all those seeking advice from him. When Murtaugh asked Stargell to be the team captain a year later, he agreed only if he could lead his own way. He could not be Clemente. Murtaugh told him he understood and wouldn’t want it any other way.20

Stargell responded to the loss of Clemente with one of the best seasons of his career. He batted .299 with 44 home runs and a league-leading 119 RBIs. He also led the league in doubles, slugging percentage, OPS, and OPS+. It still was not enough to win the league’s MVP, finishing second again, this time to Pete Rose.

At season’s end, Stargell learned he would be receiving the award he really wanted: The Roberto Clemente Award, given out to the player who exemplifies the late star on and off the field. “Of all the awards this ranks number one with me,” Stargell said, “because it identifies with Clemente, who always tried to help people.”21 He also won the Lou Gehrig Memorial Award as the player who best exhibits the character and integrity of Gehrig on and off the field.

Stargell remained one of the dominant players in the decade of the 1970s. He walloped 296 home runs, more than any other player. He capped that decade off in 1979 with a magical season at the ripe age old of 39. He won three MVP awards—for the regular season, the NLCS, and the World Series. His Series performance had similarities to Clemente’s. He batted .400 with seven extra-base hits and seven RBIs as the Pirates again beat the Orioles. This time the Bucs rose from a 3–1 deficit to win it. And it was Stargell’s home run that put the Pirates ahead for good in the seventh game.

So the 1971 season will long be remembered as the year Clemente showed the world why he was “The Great One,” and the year the Pirates changed baseball by starting the first all-minority lineup. It was also the pivotal year for Willie Stargell emerging as a complete hitter, establishing himself as a superstar for years to come, actively becoming a team leader, and helping lead the Bucs to a world championship. And in doing so, Stargell accelerated his journey to the Baseball Hall of Fame. In 1988, he was voted in on his first ballot.

BLAKE W. SHERRY is a lifelong Pittsburgh Pirates fan who resides in Dublin, Ohio. A retired Chief Operations Officer of a public retirement system, he has been a member of SABR since 1997. He co-leads the Hank Gowdy SABR Chapter in Central Ohio, and currently runs that chapter’s quarterly baseball book club. He contributed to the SABR book “Moments of Joy and Heartbreak: 66 Significant Episodes in the History of the Pittsburgh Pirates.”

Notes

1 Charles Feeney, “Willie Stargell Puts It All Together,” Baseball Digest, September 1971.

2 Willie Stargell and Tom Bird, Willie Stargell: An Autobiography (New York: Harper & Row, 1984), 140–141.

3 Bruce Markusen, The Team that Changed Baseball (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing), 2006, 19–20.

4 Jim O’Brien, “Willie at the Front,” from Baseball Hall of Fame files, April 26, 1971.

5 Feeney, “Graveyard Strolls Keep Slugger Stargell Slim,” The Sporting News, May 22, 1971.

6 Dick Young, “How Stargell’s Saigon Visit Made Him a Better Hitter,” New York Daily News, June 24, 1971.

7 Markusen, The Team that Changed Baseball, 41–42.

8 Lester Biederman, “Willie’s 3 Homers, Cardwell’s Pitching Spark Rout, 13–3,” Pittsburgh Press, June 25, 1965; Biederman, “Stargell Raps for Attention with Three Homer Salute,” Pittsburgh Press, June 8, 1968.

9 Feeney, “Willie Stargell: A Superstar At Last?” All-Star Sports, September 1971.

10 Markusen, The Team that Changed Baseball, 81.

11 Stargell and Bird, Willie Stargell: An Autobiography, 146–147, 155.

12 Roy Blount, “On the Lam With the Three Rivers Gang,” Sports Illustrated, August 2, 1971.

13 Stargell and Bird, Willie Stargell: An Autobiography, 144–145.

14 Stargell and Bird, 145.

15 Jim O’Brien, Remember Roberto (Pittsburgh: James P. O’Brien Publishing, 1994), 234.

16 Markusen, The Team that Changed Baseball, 74.

17 Markusen, 140.

18 Markusen, 181.

19 Bill Christine, “Clemente Drives Pirates to Title,” The Pirates Reader (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2003), 214.

20 Stargell and Bird, Willie Stargell: An Autobiography, 159.

21 Feeney, “Clemente Award Given to His Ex-Mate Willie,” Pittsburgh Press, April 27, 1974.