Winter Baseball in California: Separate Opportunities, Equal Talent

This article was written by Geri Driscoll Strecker

This article was published in The National Pastime: Endless Seasons: Baseball in Southern California (2011)

Mislabeling all winter baseball played in California as “California Winter League” ignores the uneven color lines that existed in that time and place.

Mislabeling all winter baseball played in California as “California Winter League” ignores the uneven color lines that existed in that time and place.For most black players during the early 1900s, baseball was a year-round occupation. Much has been written about African American involvement in the Cuban Winter League and with barnstorming teams that played against white major leaguers. However, less is known about other offseason baseball opportunities for black players, including the fact that many Negro League stars spent winters playing ball on the West Coast. Long before Satchel Paige’s All Stars faced Dizzy Dean’s barnstorming major leaguers during the 1930s, Oscar Charleston’s “Bear Cats” mauled Irish Meusel’s All Stars in Southern California during the winter of 1921–1922. Such pre- and post-season competitions between black and white teams occurred throughout the era of segregated baseball.

Among the Negro Leaguers who played winter ball on the West Coast, Raleigh “Biz” Mackey reigns supreme, playing 18 winters in the Golden State and maintaining an impressive .366 batting average with 28 home runs. Other multi-season stars include Mule Suttles (8), Norman “Turkey” Stearnes (9), and James “Cool Papa” Bell (12). Among the pitchers were Satchel Paige (56–7), Chet Brewer (43–13), and James “Cannon Ball” Willis (41–10). Wilber “Bullet” Rogan spent six winters in California and dominated both as a pitcher (42–14) and batter (.362 with 15 home runs).[fn]Center for Negro Leagues Baseball Research www.cnlbr.org/DefiningNegroLeagueBaseball/WinterLeagueTeams/tabid/59/Default.aspx.[/fn]

Among the Negro Leaguers who played winter ball on the West Coast, Raleigh “Biz” Mackey reigns supreme, playing 18 winters in the Golden State and maintaining an impressive .366 batting average with 28 home runs. Other multi-season stars include Mule Suttles (8), Norman “Turkey” Stearnes (9), and James “Cool Papa” Bell (12). Among the pitchers were Satchel Paige (56–7), Chet Brewer (43–13), and James “Cannon Ball” Willis (41–10). Wilber “Bullet” Rogan spent six winters in California and dominated both as a pitcher (42–14) and batter (.362 with 15 home runs).[fn]Center for Negro Leagues Baseball Research www.cnlbr.org/DefiningNegroLeagueBaseball/WinterLeagueTeams/tabid/59/Default.aspx.[/fn]

In his book The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (McFarland, 2002), William F. McNeil discusses opportunities that African American ballplayers had to compete against their minor and major league counterparts. However, the story is not quite so clear, and mislabeling all winter baseball played in California as “California Winter League” ignores the uneven color lines that existed in that time and place.

The season most illustrative of this point occurred during the winter of 1921–1922, when future Hall of Famers Ty Cobb, Harry Heilmann, Rogers Hornsby, George Sisler, Oscar Charleston, Raleigh “Biz” Mackey, and Jose Mendez traveled west after the regular Major League or Negro League season to play winter ball—but not against each other. That season, the official California Winter League was reserved only for major and minor league players, which meant that all participants were white. To promote attendance, the four CWL teams signed major league players as managers: San Francisco Seals, Ty Cobb (Detroit Tigers); San Francisco Missions, Harry Heilmann (Detroit Tigers); Los Angeles Angels, Rogers Hornsby (St. Louis Cardinals); Vernon Tigers, George Sisler (St. Louis Browns).

Cobb’s temper during this period was particularly volatile. In the bottom of the fourth inning of a November 19 game against Vernon, he threw a fit over a missed call (Lu Blue threw out George Sisler at second, but the umpire missed it) and refused to leave the field when ejected from the game. The chief umpire ultimately declared a forfeit, and league president Frank Chance fined Cobb $150. On November 20, the Los Angeles Times headline read, “Tyrus Cobb is Somewhat Sad,” and the article predicted the Tiger “may leave California flat on its back by never returning after the close of the present winter season. Life’s road sure is becoming rocky for the greatest ball player of all time.” He had batted only 1 for 3 the previous day and slumped out of the batting lead; meanwhile, his San Francisco Seals were mired in last place. Discontented with his CWL experience, and clearly not interested in staying to play against the Colored All Stars, Cobb left California on December 7, vowing never to play or manage winter ball there again.[fn]Los Angeles Times, November 21, 1921, B2; Los Angeles Examiner, 8 December 1921, sec. 2, 4; Los Angeles Times, 12 December 1921, 17. [/fn] Cobb’s attitude toward the black players was not unique among the major and minor leaguers.

Although Southern California provided winter opportunities for black ballplayers, during the regular season African American teams had to scramble for games, playing whatever semipro and military clubs would accept their challenge. They could not be part of a regular league because the all-white Southern California Managers’ Baseball Association held tight control over the semipro circuits. A few of the best black teams still managed to thrive, however, and the strongest during the summer of 1921 was the Alexander Giants.[fn]California Eagle, 12 August 1921, 6. [/fn]

Although Southern California provided winter opportunities for black ballplayers, during the regular season African American teams had to scramble for games, playing whatever semipro and military clubs would accept their challenge. They could not be part of a regular league because the all-white Southern California Managers’ Baseball Association held tight control over the semipro circuits. A few of the best black teams still managed to thrive, however, and the strongest during the summer of 1921 was the Alexander Giants.[fn]California Eagle, 12 August 1921, 6. [/fn]

The club had opened a new ballpark at 32nd and Long Beach Avenue in the Nevin area of Los Angeles on May 2, 1920 (interestingly, the same day the Indianapolis ABCs and Chicago Giants played the first Negro National League game in Indianapolis). During their brief 16-month history, the Alexander Giants played 142 games. In 1920, their record was 55–15–2 (.786), and in 1921 they had dominated their opponents 60–10 (.857). But in late September 1921, the Alexander Giants’ grandstand burned to the ground.[fn]California Eagle, 1 October 1921, 6. [/fn] The loss of this ballpark shifted much of the black community’s interest to another African American team, the Los Angeles White Sox.

In early October 1921, the White Sox incorporated as The White Base Ball and Amusement Association with the following officers: Frank Howard, president; J.E. Walton, secretary; J.H. Graham, treasurer; James P. White, general manager; and Alonza (Lon) Alfred Goodwin, field manager. This new business structure generated financing for establishing a new headquarters, improving the team’s ballpark, and recruiting an impressive roster for the winter season.[fn]California Eagle, 15 October 1921, 6. [/fn]

The team’s “new and well furnished” headquarters was at 1419 E. 12th Street (two miles southwest of their ballpark). This gave the management and players a convenient place to “congregate and discuss the game without infringing upon some one’s pool room and barber shop rights.” They saw this move toward professionalization of the business as “a step in the right direction.” This business structure allowed them to sustain the team in an otherwise increasingly segregationist climate. (During the winter of 1921–1922, the Ku Klux Klan moved into California and held their first recruitment rally in Los Angeles on Wednesday, January 11, with hundreds in attendance).[fn]California Eagle, 26 November 1921, 6; Los Angeles Examiner, 13 January 1922, 1. [/fn]

The White Sox played at Anderson Park, which by 1921 was better known as White Sox Park, in the Boyle Heights area of East Los Angeles.[fn]Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps for Los Angeles, California, 1906-January 1951, volume 14, 1921, plates 1417, 1418, and 1419. [/fn] The field was deemed suitable to white professional and semi-professional clubs, and its proximity to teams from the California Winter League offered the White Sox a unique opportunity to compete against assorted teams of major and minor league players. Because of the expense of fielding an all-star team and attracting strong opponents, the White Sox increased ticket prices over summer rates, to 50 cents general admission, 75 cents grandstand, and 1 dollar box seats.[fn]California Eagle, 29 October 1921, 6. [/fn]

In mid-October 1921, the California Eagle, a weekly African American newspaper in Los Angeles, announced, “During the next five months the new [White Sox] concern will devote its energy toward promoting a top notch brand of big league baseball ably managed by Alonza Alfred Goodwin [who] will have absolute charge of the maneuvers of the ball club which winters here this season.” Goodwin had been manager of the Los Angeles White Sox for ten years, and he was already “busy drafting one of the greatest aggregations of baseball performers…either black or white, gathering stars from the various clubs of the [Negro] National League.” His initial recruitment goal for the team he would call the Colored All Stars is mind-blowing: Oscar Charleston, Wilber Rogan, John Donaldson, George Carr, Hurley McNair, Walter Dobie Moore, Bob Fagan, Frank Warfield, Bill Riggins, and Bill Drake.[fn]California Eagle, 15 October 1921, 6; California Eagle, 1 October 1921, 6. [/fn] While this is not the team Goodwin ended up with, his ultimate line-up was almost as impressive:

- Oscar Charleston, cf

- George Carr, rf

- Bob Fagan, 2b

- Lemuel Hawkins, 1b

- Walter Doby Moore, ss, p

- Jose Mendez, ss

- Tom Ward, lf, rf

- Henry Blackman, 3b

- Neil Pullen, c

- Raleigh “Biz” Mackey, c

- John Taylor, p

- Jim Jeffries, p, rf

- Hurley McNair, p, lf

Many of these players were legends in professional black baseball. During the 1921 Negro National League season, Oscar Charleston had played for Charlie Mills’s St. Louis Giants. It had been this great player’s best season, with an astonishing .426 batting average. In the fifty games for which we have box scores, he stole 28 bases and made 79 hits, including 14 doubles, 10 triples, and 14 home runs. What makes this record even more impressive is that these box scores are mostly from games against top opponents, like Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants, C. I. Taylor’s Indianapolis ABCs, and the Kansas City Monarchs. While Charleston usually spent winters in Cuba (and won batting titles there in 1920, 1922, and 1924), he opted to stay in the United States during the winter of 1921–1922 and went to Los Angeles to play for Lon Goodwin’s Colored All Stars.

Because Negro National League teams back east each had different postseason barnstorming obligations, the White Sox team was not complete until late November, but they began playing games in early October. This created an opportunity for local talent to play alongside the stars. During the regular season, catcher Neal Pullen had been captain of the El Segundo team. He was skilled behind the plate but became the back-up catcher when Biz Mackey arrived from Indianapolis, where he had spent the season with C.I. Taylor’s ABCs. Another player—Henry “Heinie” Blackman—had played first base for the Alexander Giants. A threat at the plate, he had hit an inside-the-park home run during an August game.[fn]California Eagle, 19 August 1921, 6. [/fn]

The official California Winter League season—with four all-white teams—spanned from October 8 to December 11. As it was winding down, baseball promoter and Los Angeles White Sox owner Joe Pirrone signed a group of major and minor leaguers to form a white all-star team that would face his White Sox (also known as the Colored All Stars, the Colored Giants, and the Bear Cats) during the remainder of the winter. Pirrone secured Irish Meusel to manage the team and recruited several notable players:

- Bill McKechnie (Pittsburgh Pirates/Minneapolis Millers AA)

- George Cutshaw (Pittsburgh Pirates)

- Tony Brottem (Pittsburgh Pirates)

- Lew Fonseca (Cincinnati Reds)

- Tony Boeckel (Boston Braves)

- Earl Sheely (Chicago White Sox)

- Lee Thompson (Chicago White Sox)

- John “Red” Oldham (Detroit Tigers)

- Lu Blue (Detroit Tigers)

- Don Rader (Philadelphia Phillies)

- Bob Fisher (Minneapolis Millers AA)

- Rowdy Elliott (Sacramento PCL)

- Slim Love (Vernon PCL)

Some of these men had also been playing on CWL teams and gradually joined Pirrone’s or other all-star teams as the CWL schedule wound down. This blurs the boundaries between league competition and other non-sanctioned games, but the mix of major and minor league talent still offers a rare opportunity to see how African American players performed against their white contemporaries.

While the CWL was still in full swing, the Los Angeles White Sox defeated “Pirrone’s minor leaguers” (mostly players from the Pacific Coast League), 6–4, on October 9, in their first fully competitive game of the 1921–1922 winter season. The regular season opener came three weeks later on October 29, with another victory (4–0) against Joe Pirrone’s All Stars, which by then had more major leaguers in the line-up. To gather public interest and show off their new uniforms, the White Sox held a big parade beginning at noon and leading to the ballpark for the afternoon game.[fn]California Eagle, 29 October 1921, 6. [/fn]

While the CWL was still in full swing, the Los Angeles White Sox defeated “Pirrone’s minor leaguers” (mostly players from the Pacific Coast League), 6–4, on October 9, in their first fully competitive game of the 1921–1922 winter season. The regular season opener came three weeks later on October 29, with another victory (4–0) against Joe Pirrone’s All Stars, which by then had more major leaguers in the line-up. To gather public interest and show off their new uniforms, the White Sox held a big parade beginning at noon and leading to the ballpark for the afternoon game.[fn]California Eagle, 29 October 1921, 6. [/fn]

During the first half of their winter season, the Colored All Stars played well but struggled with Sunday games, losing five weeks in a row. In an October 30 game against Pirrone’s All Stars, the White Sox faced Red Oldham, who had an 11–14 record for the Detroit Tigers in 1921. The black team batted well and scored 8 runs, but Baugh, a less known local black pitcher, gave up 6 runs in 11?3 innings, so Goodwin sent Biz Mackey to the mound. Amazingly, the White Sox came back to an 8–8 tie in the eighth, but then the white All Stars pulled ahead again, winning the game, 10–8.[fn]California Eagle, 5 November 1921, 6. [/fn]

The following Sunday, November 6, the White Sox faced Pirrone’s All Stars again. In a questionable decision, Goodwin chose to pitch John “Steel Arm” Taylor (brother of C.I., Ben, and Candy Jim). On any other day, this would have been a sure bet, but the Chicago American Giants ace had gotten off the train from Illinois a mere four hours before the game and had not trained for several weeks. The California Eagle reported, “The results are sad, sad to relate without the free use of a bandana…. The first five men to face Mr. Taylor piled enough lumber on him to build a hotel.” After 4 runs in only 7 minutes, with no outs, Goodwin pulled him and put in McNair. The reliever fared better but was still no match for major leaguer Bill Pertica, who had a 14–10 record with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1921. The White Sox lost, 12–9.[fn]California Eagle, 12 November 1921, 6. [/fn]

On November 12, Taylor took the mound again against Fisher’s All Stars (another team of major and minor leaguers). This time he was rested and ready and shut out his opponents, 4–0. The California Eagle reported, “John did about everything to Bob Fisher’s big bush leaguers that the rules on baseball etiquette call for: he walked none, allowed 2 little singles, poled a triple and single himself and left four standing at the platter wondering where the elusive pill went through their stick.”[fn]California Eagle, 19 November 1921, 6. [/fn] The Eagle’s “Sports and Amusements” columnist William Mells Watson scored most of the games and contributed colorful commentary in his weekly summaries.

On November 15, 16, and 17, the White Sox easily swept a mid-week series from the Dyas All Stars, yet another white team. Then the following week, the already strong White Sox began transforming into a powerhouse when Cuban Jose Mendez of the Kansas City Monarchs arrived and replaced Doby Moore at shortstop.[fn]Los Angeles Times, 17 November 1921, sports 3; California Eagle, 19 November 1921, 6; Los Angeles Examiner, 17 November 1921, sec. 2, 4. [/fn] The unpredictability of game outcomes shows just how evenly matched teams were. On November 19 in a game against the Pacific Nationals, McNair gave up five runs in two innings, so the manager sent in “the dependable utility wonder, Raleigh Mackey, [who] stepped on the slab and won his struggle 11 to 7.” Pitching is always fickle, and the following day, seasoned veteran John Taylor lost the first game of a doubleheader, 6–3. Jim Jeffries, from the Indianapolis ABCs, won his game, 8–5.[fn]Los Angeles Times, 20 November 1921, A9; California Eagle, 26 November 1921, 6; Los Angeles Times, 21 November 1921, B1. [/fn]

In late November, more top minor and major leaguers were showing up on opponents’ rosters. On November 24, John Taylor gave up only four hits against Edington’s major league stars, winning 2–1. His opponents on the mound were Slim Love of the CWL-leading Vernon Tigers and George “Sarge” Connally, who had debuted with the Chicago White Sox during the regular season.[fn]Los Angeles Times, 25 November 1921, C3. [/fn]

In announcing the Colored All Stars’ next series against Calpaco, the Los Angeles Timesnoted, “Oscar Charleston, the colored Babe Ruth, arrived from St. Louis yesterday and immediately joined White’s aggregation.” The following day, the Timeselaborated, “With the signing of Charleston, home-run swatter, the L. A. White Sox club is now complete. Charleston hails from the St. Louis Giants and is said to have established a record last summer for home runs in the Negro National League.” Everyone expected the slugger to “attract a crowd.”

The Calpaco team was a mix of major and minor leaguers, featuring Blue and Oldham (Detroit), Pinch Thomas (Cleveland), James Washburn (Wichita WL), and Ray Bates (Seattle PCL).[fn]Los Angeles Times, 25 November 1921, C3; Los Angeles Times, 26 November 1921, B11; Los Angeles Times, 26 November 1921, B11. [/fn] The Colored All Stars won the Saturday game 4-2 but continued their string of Sunday losses in the first game of a doubleheader, followed by a tie in the second, when the umpire called it due to darkness in the sixth. The California Eaglecommented, “Notwithstanding that Oscar Charleston (the famous Colored Babe Ruth of the St. Louis Giants) was camping in the outfield, still Jim White’s ‘Bear Cats’ failed to grab off either of the Sabbath twin performances with the big league Calpaco nine.” Charleston was 1 for 4 in the first Sunday game and 1 for 3 in the second (a triple and a single).[fn]Los Angeles Times, 27 November 1921, A10; Los Angels Times, 30 November 1921, C3; California Eagle, 3 December 1921, 6. [/fn]

While Southern California’s mild climate is ideal for year-round baseball, the weather still caused problems. Rain and sometimes high winds could wreak havoc with the schedule. On December 3, a game versus Calpaco was cancelled when a “rip-roaring Santa Ana storm” blew down “the entire north and south side fence [and left it] lying mangled on the ground.” On December 17 and 18, it rained so hard that the California Eagledeclared that “fish were swimming around the bases, bringing sorrow to the management and disappointment to the several thousand fans.” Rainouts were so common that the California Winter League had actually spent $3,000 on a rainout insurance policy; teams collected $34,000. The Colored All Stars did not have that luxury and suffered at the will of the weather, sometimes losing an entire series, such as around Christmas, when rain claimed three games against the Vernon Tigers. Record crowds had been expected at White Sox Park.[fn]California Eagle, 10 December 1921, 6; California Eagle, 24 December 1921, 6: Los Angeles Times, 13 December 1921, C3. [/fn]

Fortunately, in good weather the games without rain drew many fans. In early December, with Charleston, Mendez, and the rest of his starters now in full form, Goodwin enjoyed increasing coverage in both black and white newspapers. The latter even began praising black players. On the morning of a December 4 game against Calpaco, the Los Angeles Timespraised Charleston as the “home run swatter of the St. Louis Giants.” Then, after the Colored All Stars had lost five straight Sunday games, John Taylor defeated Red Oldham, 7–2. The Timeswrote, Calpaco was “unable to stem the tide of hits.” Mendez and Fagan had both hit home runs, while Charleston went 1 for 3, was hit by a pitch, and scored twice. During the first inning, Calpaco’s shortstop became angry after a called third strike and pushed the umpire. Surprisingly, such tensions were actually rare in contests between the Colored All Stars and white professional teams.[fn]Los Angeles Times, 4 December 1921, A10; Los Angeles Times, 5 December 1921, B9. [/fn]

Goodwin had assembled a crack team and on any given day any player could offer a tremendous performance. Often that was Mackey, the team’s catcher, who at the time was still young and fast enough to be a threat on the basepaths. A December 11 pitchers’ duel against Art Krueger’s All-Stars was tied “in the eighth and…drifted into the eleventh still knotted when old man Mackey hammered out a sweet two sacker and skeeted across the gravy dish when pinch hitter Henry Blackman broke up the argument with a timely single.”[fn]California Eagle, 17 December 1921, 6. [/fn]

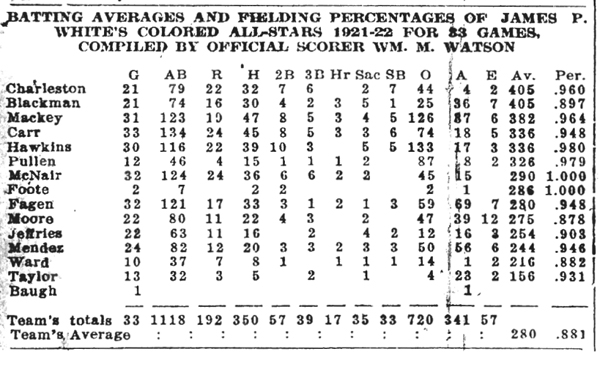

Kruger’s team included Fred Haney (former Angel, PCL), Carter Elliott (Chicago Cubs), and Slim Love (Vernon, PCL, and soon-to-be CWL champions). But these men were no match for the White Sox offense. On December 13, the Los Angeles Timesgave the following statistics: “Lem Hawkins and ‘Slim’ Blackman of the L.A. White Sox club are both hitting an even .400 for the fifteen games of winter ball… Other leading batters are Mackey .351; Charleston .300; Foote .286; Fagan .285.” A few days later, the mainstream paper conceded, “White’s team is composed of high class professional players.”[fn]Los Angeles Times, 13 December 1921, C2; Los Angeles Times, 17 December 1921, B14. [/fn]

In mid-December, White Sox manager Lon Goodwin retired and left Jim White to manage the team with Oscar Charleston as captain. The California Eagle called Goodwin “the greatest baseball manager in the West.” But, they added, “Charleston is thoroughly capable, having acted in this capacity in the Negro National League many years.” This was also the week when the California Winter League was wrapping up, and the Eaglecommented that the league’s official closing would be “a relief to the gate receipts at the White Sox Park.” After the Vernon Tigers won the California Winter League pennant, comedian Carl Sawyer took over the team and began playing games against the Colored All Stars. Vernon had their entire championship team intact, except for George Sisler and Jimmy Austin. Their manager was Irish Meusel, outfielder of the 1921 World Series champion New York Giants. On December 17 the Tigers won, 5–3, with John Taylor defeating Sam Lewis.[fn]California Eagle, 17 December 1921, 6; California Eagle, 17 December 1921, 6; California Eagle, 24 December 1921, 6. [/fn]

On January 7 and 8, 1922, the Colored All Stars made easy work of Calpaco in a three-game series (9–3, 4–3, 14–0). The California Eaglewrote, “Jim White’s chief of staff, Oscar Charleston, the Colored king of swat and his pack of twin-six assistants, with malice aforethought, last weekend and Sabbath coaxed the high-toned and prettily uniformed squad of Calpaco diamond stars into their bull-pen and then turned on ’em and smacked them for three rows of Chinese pot houses in as many games.” The first game on Sunday took eleven innings. Then, “Manager Charleston smacked a triple; Mackey…whaled a sacrifice to center and Oscar railroaded home at least three inches to the good.” Charleston went 3-for-5 in that game. Mackey pitched, and “ten [white opponents] left with the wood on their shoulders and sorrow in their hearts.”[fn]California Eagle, 14 January 1922, 6; California Eagle, 14 January 1922, 6. [/fn]

The Calpaco team included “Red” Oldham (Detroit), Chet Thomas (Hartford EL), Ray Bates (Seattle PCL; Indians 1913, Philadelphia Athletics 1917), Pete Schneider (Cincinnati 1914–1918; Yankees 1919; Vernon 1921 PCL), Harold “Rowdy” Elliott (Sacramento PCL; Boston Braves 1910, Cubs 1916–1918, Dodgers 1920), and Johnny “Trolley Line” Butler (Wichita WL).

After sweeping Calpaco, the Colored All Stars again turned their attention to the Vernon team. Tigers coach Irish Meusel and his brother Bob, of the AL champion New York Yankees, both wanted to play for the team, as did Johnny Rawlings (Giants) and Bill Piercy (Yankees). However, fearing that top major leaguers from the World Series might fall in contests against top Negro Leaguers, Commissioner Landis had barred them from barnstorming. The players petitioned Landis to reverse his ruling, which he finally did on January 9. Bob and Irish Meusel, and John Rawlings all joined the Vernon Tigers for a five-game series with White’s Colored All Stars, beginning January 14. Coach Meusel also signed pitcher Bill Pertica of the St. Louis Cardinals to pitch the Sunday game on the 15th. The Vernon team’s expected lineup included seven current and former major leaguers: Johnny Bassler and Lu Blue (Detroit), Irish Meusel and Johnny Rawlings (NY Giants), Bob Meusel (Yankees), Bill Pertica (St. Louis Cardinals), Tony Boeckel (Boston Braves), and Carl Sawyer (of Vernon, but formerly with Washington Nationals).[fn]Los Angeles Examiner, 31 December 1921, sec. 1, 13; Los Angeles Examiner, 10 January 1921, sec. 1, 12; Los Angeles Examiner, 12 January 1922, sec. 1, 15. [/fn]

The Colored All Stars won the opening game against Vernon, 3–2. Charleston’s men had been behind 2–0 until the ninth but then rallied with three hits and three runs. The crowd was the biggest of the season thus far, and fans lined the outfield, topped only by the following day’s “Sabbath mob [which] was the greatest ever crammed in the enclosure.” Perhaps fans were there to see the White Sox captain even more than the major leaguers. The Eaglewrote, “If brainy Oscar Charleston wasn’t pulling one of his famous drag-shot bunts safely, he was lambasting a double or hot and sizzling grass cutter to the outfield.” The Vernon team won the Sunday game, but only by a single run, 7–6. John Taylor had given up two home runs, but Charleston went 3-for-4 with a double and a stolen base. By Tuesday, Commissioner Landis was reconsidering the wisdom of allowing MLB players to participate on an “all-professional team” in such match-ups.[fn]Los Angeles Examiner, 20 January 1922, sec. 1, 14; California Eagle, 21 January 1922, 6; Los Angeles Examiner, 16 January 1922, sec. 1, 14; Los Angeles Examiner, 17 January 1922, sec. 1, 10. [/fn] The Colored All Stars also won their next two games against Vernon. The Los Angeles Examiner called the contests “important tilts” and emphasized how much the major leaguers had been training for the games. After their 4–3 victory on January 21, the Examiner headline read, “Sox Trounce All-Stars.” And the following day, Charleston, Mackey, and Carr all hit triples off Bill Pertica in the 5–4 win. Examiner sportswriter Frank A. Kerwin also noted that Yankees slugger Bob Meusel was “riled up” over these “defeats of the Majors.”[fn]Los Angeles Examiner, 21 January 1922, sec. 1, 12; Los Angeles Examiner, 22 January 1922, sec. 1, 16; Los Angeles Examiner, 23 January 1922, sec. 1, 12; Los Angeles Examiner, 28 January 1922, sec. 1, 12. [/fn]

On January 28 and 29, the Vernon-White Sox rivalry continued, with a set of “winner take all” contests, meaning that the victor of each game would claim 100 percent of the gate. Bill Pertica won the Saturday contest for Vernon, 15–10, but it was a total slugfest, with 2 home runs, 7 triples (2 by Charleston), and 9 doubles. The Sunday game was another rainout. The following weekend, the “winner take all” series continued, with the Colored Stars taking the Saturday game 5–4, and Vernon claiming the Sabbath contest, 5–2. This left the season at 4–3, in favor of the Colored Stars—with five of these games won by only a single run. Before the Saturday game, the Examiner had announced that these would likely be the last games, but with the White Sox ahead, they planned one more weekend.[fn]Los Angeles Examiner, 29 January 1922, sec. 1, 18; Los Angeles Examiner, 5 February 1922, sec. 1, 13; Los Angeles Examiner, 6 February 1922, sec. 1, 14. [/fn]

The game on February 11 was called off due to wet grounds, and the Colored Stars took the Sunday contest, 13–8, bringing the winter series to 5–3. The Los Angeles Examineradmitted, “White’s colored All Stars walked away with the game” and even praised the team leader: “Oscar Charleston, slugging outfielder, hit three doubles.” The teams met only twice more.[fn]Los Angeles Examiner, 12 February 1922, sec. 1, 14;13 February 1922, sec. 2, 4. [/fn]Vernon took the penultimate game, but after the February 25 capstone, The California Eagle declared: “[John] Taylor White Washes Meusel’s Majors 6 to 0 in Last Clash.” The story mocked the losers:

Evidently Irish and Bobby Meusel didn’t care about facing Oscar and his gang in the last fracas of their schedule which ended so disastrously last Saturday as neither of them showed up for hostilities so the results were aerographed to them in order to cheer them up as they start on their way to training camp—Meuselites “Zero,” Colored Hope Destroyers 6.[fn]California Eagle, 4 March 1922, 6. [/fn]

Besides proving himself an able leader, Charleston generated impressive offensive performance, batting .405 overall during the winter season. In 21 known games, he had 79 at-bats, with 32 hits, 6 triples, and 7 doubles, plus 7 stolen bases and 22 runs scored. On March 4, California Eaglesports writer William Mells Watson celebrated Charleston:

OSCAR CHARLESTON KING OF SWATTERS THROUGHOUT SEASON HITS .405, FIELDS .960 When general manager Jim White drafted “bambino” Oscar Charleston to the Angel City last fall, he imported without a doubt the second greatest living baseball performer in the entire universe, the great Babe Ruth being his only peer.[fn]California Eagle, 4 March 1922, 6.[/fn]

After claiming a definitive victory over the major leaguers, 7 –4, the Colored All Stars fell to financial pressures. Leaving Los Angeles, they barnstormed against local and semipro teams throughout southern and central California, where they continued dominating all opponents.

Studying the 1921–1922 California Winter League and the state’s less organized barnstorming season demonstrates several important points. Most importantly, it proves that these Negro League players could stand up against major leaguers. This justified Commissioner Landis’s concerns about major league championship players facing Negro Leagues All Stars during the offseason. While Ty Cobb chose to leave California before he might have faced Oscar Charleston and the White Sox, we still learn something about these players. In the CWL, the San Francisco Seals’ weak season showed that Cobb was not an effective manager and that his playing skills were becoming less reliable. Meanwhile, when Charleston took over managing the Colored All Stars, he demonstrated great potential, which would later show in his successful career as a manager with several Negro League teams, most notably the 1932–1938 Pittsburgh Crawfords.

GERI STRECKER teaches English and Sport Studies at Ball State University. She is writing a biography of Hall of Famer Oscar Charleston and a history of baseball and diplomacy in the Philippines prior to World War I. She is also editing a collection of columns by Dave Wyatt, the first great black sportswriter. Her article “The Rise and Fall of Greenlee Field: Biography of a Ballpark” (Black Ball, Fall 2009) received the McFarland-SABR Research Award in 2009. She also won the award in 2010 for “And the Public Has Been Left to Guess the Secret: Questioning the Authorship of ‘The Great Match, and Other Matches’ (1877)”.