Working Overtime: Wilbur Wood, Johnny Sain and the White Sox Two-Days’ Rest Experiment of the 1970s

This article was written by Don Zminda

This article was published in Spring 2016 Baseball Research Journal

In Game Seven of the 2014 World Series, Madison Bumgarner of the San Francisco Giants entered the contest in the fifth inning with his team leading the Kansas City Royals, 3–2. Bumgarner, working on two days’ rest after a complete-game shutout victory over the Royals in game five, proceeded to pitch five scoreless innings to secure the championship and electrify the baseball world.1 “Now he belongs to history,” wrote Tyler Kepner in the next morning’s New York Times. Kepner went on to praise Bumgarner for “his excellence in shouldering a workload that brings to mind the durable and dominant aces of old.”2

In Game Seven of the 2014 World Series, Madison Bumgarner of the San Francisco Giants entered the contest in the fifth inning with his team leading the Kansas City Royals, 3–2. Bumgarner, working on two days’ rest after a complete-game shutout victory over the Royals in game five, proceeded to pitch five scoreless innings to secure the championship and electrify the baseball world.1 “Now he belongs to history,” wrote Tyler Kepner in the next morning’s New York Times. Kepner went on to praise Bumgarner for “his excellence in shouldering a workload that brings to mind the durable and dominant aces of old.”2

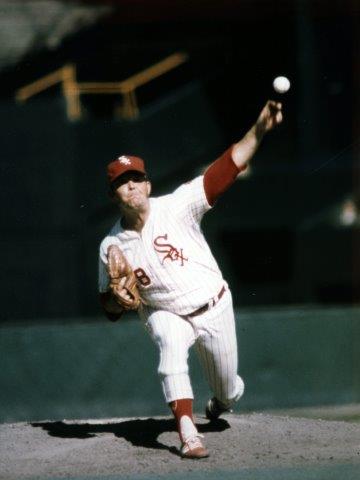

Wilbur Wood never performed any postseason heroics during a 17-year career that produced 164 major league victories. In fact, none of the three MLB teams he pitched for even reached the postseason during his career. But any discussion of “the durable and dominant aces of old” should rightly include the lefty knuckleballer. From 1971 through 1975, Wood won 106 games for the Chicago White Sox, working an average of 3361⁄3 innings a year. Nearly 30 percent of Wood’s starts during that five-year period—66 of 224—came while working on two days’ rest or fewer since his previous start (what we’ll call “short rest” for the duration of this article3). In the 102-season span from 1914 through 2015, only one major league pitcher topped Wood’s 70 career starts on short rest: a durable and dominant ace named Grover Cleveland Alexander, who logged 72 short-rest starts between 1914 and 1928.4

How did Wilbur Wood, a pitcher who had worked primarily in relief prior to the 1971 season, become an iron-man starter with a workload out of the deadball era? And why did he pretty much stop pitching on short rest after 1975? The answers lie in the confluence of Wood’s career with that of Johnny Sain, a successful pitcher who became an even more successful pitching coach. It was Sain, along with White Sox manager Chuck Tanner, who turned Wood into a starting pitcher in spring 1971. Johnny Sain believed that nothing was wrong with working a pitcher hard—one of his quotations about a pitcher’s arm was, “It’ll rust out before it wears out.”5 And in the soft-tossing knuckleballer Wood, he found the ideal candidate for pushing his pitching theories to the limit.

Like Wilbur Wood, John Franklin Sain achieved success as a major-league pitcher without benefit of a blazing fastball. As Jan Finkel wrote of the right-hander, “Sain came to realize and accept that although he was large for his era at 6-feet-2 and 180–200 pounds, he didn’t have high-octane velocity. Accordingly, he’d have to rely on mechanics, finesse and guile….”6 Beginning in 1946, Sain won 20 or more games four times in five years for the Boston Braves. In his best season, 1948, he helped the Braves reach their first World Series in 34 years, while leading the National League in wins (24), games started (39), innings pitched (3142⁄3) and complete games (28). Notably, Sain’s 1948 season included eight starts on two days’ rest. Six of those eight starts came in a 25-day stretch from August 24 through September 17. Over that period, Sain threw eight straight complete games while going 6–2 with a 1.57 ERA as the Braves neared the pennant.7

Sain’s major-league career ended in 1955, and four years later he returned to the majors as pitching coach of the Kansas City Athletics. He didn’t earn much notoriety with an A’s team that went 66–88, but after a year out of baseball, Sain returned to the game in 1961 as pitching coach of the New York Yankees. Jan Finkel wrote that with the powerful Yankees “Sain showed what he could do with good material.”8 Under Sain’s tutelage, Whitey Ford—who had never won more than 19 games in any of his previous nine major league seasons—went 25–4 in 1961 and won the Cy Young Award for the World Series champion Yankees. In 1962 Ralph Terry had his only 20-win season as the Yankees repeated as champions. Then in 1963, both Ford and Jim Bouton won 20-plus games for the Yanks, who captured another American League pennant before being swept in the World Series by the Los Angeles Dodgers. Bouton would later refer to Sain as “the greatest pitching coach who ever lived.”9

Sain left the Yankees after the 1963 season—amid conflicting stories about whether he resigned or was fired—but returned to the majors in 1965 as pitching coach of the Minnesota Twins. Sain’s 1965 Twins included a first-time 20-game winner (Jim “Mudcat” Grant), and again his team won the AL pennant. The Twins finished second in 1966, but Sain had another first-time 20-game winner in Jim Kaat, who won a career-high 25 games. Kaat, who led the American League in games started in both 1965 and 1966, started five games on short rest in each season. Like Jim Bouton, Kaat was full of praise for his pitching coach. “If I’d had Johnny Sain as my pitching coach for 10 years during my career,” he said in a 2015 interview, “I’d have had some of the best years in the history of the game.”10

Despite his success with the Twins, Sain was fired after the 1966 season, and moved on to Mayo Smith’s Detroit Tigers.11 In 1967 Sain had yet another first-time 20-game winner, Earl Wilson, for a team that finished one game behind the pennant-winning Boston Red Sox. In 1968 the Tigers won their first pennant and World Series championship since 1945; this time Johnny Sain’s mound staff included the major leagues’ first 30-game winner since 1934, Denny McLain (who went 3–0 in three starts on two days’ rest in 1968). Despite that success, Sain’s career as a pitching coach took a familiar turn when the Tigers fired him in August 1969.12

In 1970, Sain spent most of the season as a roving minor-league instructor in the California Angels’ farm system. He became friends with Chuck Tanner, the manager of the Angels’ Pacific Coast League farm team in Hawaii, and when Tanner was named manager of the White Sox that September, he brought Sain along as his pitching coach.13 Sain and Tanner had their work cut out for them: the last-place Sox were on their way to a franchise-record 106 losses, ranking last in the majors with a 4.54 team ERA. The team obviously needed rebuilding, and one player who Tanner and Sain saw as part of the rebuilding effort was the staff leader in saves (with 21): Wilbur Wood. With the Sox starting rotation needing a major upgrade—in 1970, veteran Tommy John was the only Sox starter with 10-plus games started who posted an ERA under 4.75—they decided to shift Wood from reliever to starter.14

Wilbur Forrester Wood, a native of the Boston area (Cambridge), led Belmont High to the state championship in 1959, his junior year, as a “self-described fastball-curveball pitcher.”15 Wood threw four no-hitters and posted a 24–2 record in high school, drawing interest from a number of major league teams before signing with the Boston Red Sox for “a bonus variously reported from $25,000 to $50,000.”16 But after making his major league debut with Boston at age 19 in 1961, Wood went 0–5 for the Sox in several trials over the next four seasons before the team released him to Seattle of the Pacific Coast League in May of 1964. “The little sonofagun just couldn’t throw hard enough,” said Red Sox manager Johnny Pesky.17

The White Sox

After Wood posted a 15–8 record for the Seattle Rainiers in 1964, the Pittsburgh Pirates purchased his contract in September. Pittsburgh used Wood mostly in relief in 1965 before sending him back to the minor leagues. The White Sox acquired Wood in a trade with Pittsburgh for left-hander Juan Pizarro following the 1966 season, and in 1967 Wood made the Sox roster as a relief pitcher and occasional starter. In the Sox bullpen, Wood—only a part-time knuckleballer when he joined the team—began working with one of the all-time masters of the pitch, Sox reliever Hoyt Wilhelm. The future Hall of Famer told Wood, “You either throw the knuckleball all the time or not at all. It’s not a part-time pitch.”18 Utilizing tips from Wilhelm, Wood blossomed into one of the most effective, and durable, relievers in baseball. From 1968 to 1970 Wood led the American League in games pitched each year, setting a single-season major league record (later broken) with 88 appearances in 1968. His 3862⁄3 relief innings over that three-year span were the most in baseball.

Entering the 1971 season, Wood had started 21 games in nine major league seasons, going 5–10 with a 3.99 ERA as a starter; he had appeared in 344 games as a reliever, posting a 32–36 record with a 2.67 ERA. Put into the number-four spot in the rotation after Joel Horlen suffered a knee injury, Wood commented that “I never got any work because of all the off days early in the season.”19 Wood didn’t win his first game as a starter until May 2, but by the All-Star break he had a 9–5 record and ranked second in the American League with a 1.69 ERA. Along with advocating Wood’s move from reliever to starter, according to Pat Jordan, Sain “made one other suggestion to Wood, and that was he pitch often with only two days’ rest. Sain felt that as a knuckleballer, Wood put less strain on his arm than did other pitchers with more orthodox stuff, and therefore he could absorb the extra work with ease.”20

Wood made his first start on two days’ rest on June 30, 1971, in an 8–3 complete-game victory over the Milwaukee Brewers. From then until the end of the season, he started 14 times on two days’ rest, going 8–4 with a 1.86 ERA in those games. The Sox won 10 of the 14 starts. “The more he pitches, the more it helps the club,” Sain said about Wood in August of 1971. “He loves the work and it doesn’t bother him.”21 Wood himself was so comfortable with his heavy workload that in a Sporting News story the same month, he told Jerome Holtzman that “he’d love to try” starting both games of a doubleheader. “If you have a nice and easy delivery [in the first game] and don’t have to throw too many pitches,” Wood said, “I don’t think it would be too hard to pitch the second game, too.”22

By season’s end, Wood had started 42 games (he also worked twice in relief) and pitched 334 innings while going 22–13 with a 1.91 ERA. He finished second in the league in ERA behind Vida Blue (1.82) of the Oakland Athletics. In the Cy Young Award balloting, Wood finished third behind Blue and 25-game winner Mickey Lolich of the Detroit Tigers, a former Johnny Sain protégé who worked a staggering 376 innings in 1971. The short-rest experiment with Wood was considered a success, and the White Sox plan for 1972 was for more of the same. “Wood is proof that pitchers can work more often,” Sain told David Condon of the Chicago Tribune in spring training in 1972. “I’ve known many who could do the job with only two days’ rest.… But Wood has to be tops.”23

With Wood leading the mound staff, the White Sox had improved by 23 wins from 1970 to 1971, finishing third in the American League West with a 79–83 record. Hoping to contend for a division title in 1972, the club made several trades over the 1971–72 off-season. The moves included trading the team’s third-leading winner in 1971, Tommy John, to the Los Angeles Dodgers in a deal that netted slugger Dick Allen, and replacing John in the rotation with right-hander Stan Bahnsen, acquired from the Yankees for infielder Rich McKinney. But perhaps the club’s boldest move for 1972 was a commitment to using Wood on two days’ rest throughout the season, while also giving Bahnsen, Tom Bradley, and number-four starter Dave Lemonds occasional short-rest starts.

Wood started 25 times on two days’ rest during the 1972 season, the most short-rest starts for any major league pitcher since at least 1914 (This article utilized the Retrosheet and STATS LLC databases, which included day-by-day player and team data back to 1914).24 Bahnsen and Bradley each started eight games on two days’ rest, and Lemonds made three short-rest starts. Like Wood, who posted a 2.62 ERA in his 25 starts on two days’ rest in 1972, neither Bahnsen nor Bradley had any issues with pitching on short rest.25 “I actually feel stronger in the games with only two days’ rest,” Bradley told the Chicago Tribune. Bahnsen agreed. “I’ve felt strong,” he told the Tribune about starting games on short rest. “I think they have shown that a lot of the theory of rest is a mental thing.”26 The results seemed to back what Bahnsen and Bradley were saying. As a group, White Sox starting pitchers posted a 3.04 ERA in their 44 starts on two days’ rest in 1972, a figure actually a shade lower than the club’s 3.12 ERA in their 110 starts with three or more days’ rest. Overall, the team’s 44 starts with two days’ rest or fewer between starts was the most by a major league team since the 1918 Philadelphia Athletics. (See Table 1.)

Table 1: Most pitcher starts with 2 or fewer days’ rest, 1914-2015

| YR | TEAM | STARTS | TEAM W-L | ERA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1918 | Philadelphia Athletics | 47 | 18-28 | 3.19 |

| 1972 | Chicago White Sox | 44 | 23-21 | 3.04 |

| 1973 | Chicago White Sox | 41 | 23-18 | 3.62 |

| 1916 | Philadelphia Phillies | 39 | 25-13 | 2.02 |

| 1918 | Cincinnati Reds | 39 | 23-16 | 2.78 |

| 1914 | Washington Senators | 38 | 22-15 | 2.37 |

| 1917 | Cincinnati Reds | 36 | 20-14 | 2.14 |

| 1922 | Detroit Tigers | 35 | 22-13 | 3.66 |

| 1916 | Boston Braves | 33 | 18-12 | 1.66 |

(Source: Sam Howland, STATS LLC)

The demands on Wood’s durable left arm in 1972 were often staggering. A frequent pattern for Wood that year was to alternate a start on three days’ rest with one on two days’ rest—in essence, starting two games a week. But at times Sain and Tanner asked him to do even more. During one 16-day period from June 20 to July 5, Wood started six straight times on two days’ rest. (The Sox lost five of the six games, though Wood posted a 3.43 ERA during the period.) During another 14-day span from July 30 to August 12, Wood started five games, including four on two days’ rest, and threw four complete games; the last start was an 11-inning, two-hit victory over the Oakland Athletics that put the Sox in first place in the AL West race by one percentage point over the A’s. This time Wood and the Sox won four of the five games, with Wood posting a 1.00 ERA.

With the numerous short-rest starts made by Wood, Bahnsen, and Bradley playing a big role, Chicago’s top three starters found themselves taking on a heavy workload. Between Wood (49 games started), Bahnsen (41), and Bradley (40), the trio started 84.4 percent of the club’s 154 games in the strike-shortened 1972 season, the highest percentage of starts by a team’s three most-frequently used starters since Joe McGinnity, Christy Mathewson, and Luther “Dummy” Taylor of the 1903 New York Giants started 85.2 percent of the Giants’ 142 games.27 As for Wood, his 49 games started in 1972 were the most for any MLB pitcher since Ed Walsh of the White Sox recorded the same number of starts in 1908, and his 376.2 innings the most since Pete Alexander worked 388 innings for the 1917 Phillies.

Tanner, Sain, and company weren’t performing a lab experiment in 1972, of course; they were trying to win a division title. With Wood, Bahnsen, and Bradley leading the mound staff and first baseman Dick Allen on his way to the AL Most Valuable Player award, the team made a strong challenge to the defending Western Division champion Athletics. The Sox led the division as late as the morning of August 29, but the team went 16–17 the rest of the way, finishing in second place, five and a half games behind Oakland. Despite the disappointing finish, the season was widely seen as a triumph for the South Siders, only two years removed from their 106-loss 1970 campaign. Along with Allen’s MVP Award, The Sporting News gave Tanner its 1972 Manager of the Year award and named White Sox Director of Player Personnel Roland Hemond Major League Executive of the Year. Wood, who finished the year 24–17 with a 2.51 ERA, ran just behind Gaylord Perry of the Indians in the AL Cy Young Award voting.

In truth, the White Sox were probably a little lucky to go 87–67 in 1972. The club won an MLB-high 38 one-run games in ’72, and their .655 (38–20) win average in one-run contests was best in the American League. According to Bill James’ “Pythagorean” formula, which projects a club’s won-lost record based on its runs scored and allowed, the 1972 White Sox won six more games than expected. Additionally, despite (or perhaps, in part, because of) all the games started by the trio of Wood, Bahnsen, and Bradley, the White Sox ranked eighth in the 12-team American League in ERA (3.12). The starting rotation also showed signs of fatigue over the last six weeks of the season. From opening day through August 19, Sox starting pitchers had an overall record of 53–37 (.589) with a 2.92 ERA; over the remainder of the season, the starters went 10–18 (.357) with a 3.61 ERA.

Nonetheless, the White Sox continued to use Wood regularly on short rest in 1973, along with occasional starts on two days’ rest for Bahnsen and newly-acquired Steve Stone, obtained (with outfielder Ken Henderson) from the San Francisco Giants for Tom Bradley. The new number-four starter, 36-year-old knuckleballer Eddie Fisher, was also a candidate for occasional short-rest starts. The Sox started the season strongly, and by the end of May led the American League West by three games at 27–15. Thirteen of those 27 wins belonged to Wood, who had started 15 of the team’s 42 games, plus a five-inning relief stint. The relief appearance came on May 26, two days after Wood had worked eight and two-thirds innings in a victory over the California Angels. Two days later, on May 28, Wood threw a four-hit complete-game shutout at the Cleveland Indians. At that point Wood had a 13–3 record and a 1.71 ERA in 1311⁄3 innings—33 more innings than he had logged by the end of May in 1972. His early-season success was one of the biggest stories in baseball, engendering a cover story (“Wizard with a Knuckler”) in the June 4 edition of Sports Illustrated.

But the rest of 1973 proved to be a struggle for Wood and the White Sox. Wood lost his first two starts in June, allowing 12 runs and 19 hits in 122⁄3 innings. From June 1 to the end of the season, he posted an 11–17 mark with a 4.47 ERA in 33 starts. Over that same time span, the White Sox were 20 games under .500 (50–70) and ultimately finished fifth in the six-team AL West with a 77–85 record. Projected as a possible 30-game winner early in the year, Wood finished 24–20, becoming the first major league pitcher since Walter Johnson in 1916 to both win and lose 20-plus games in the same season. Stan Bahnsen (18–21) also slumped after a strong start; Bahnsen, 15–11 with a 2.76 ERA after a victory over the Texas Rangers on August 5, went 3–10 with a 5.86 ERA the rest of the way.

The nadir for Wood in 1973 most likely came on July 20, when the White Sox took on the Yankees in a twi-night doubleheader at Yankee Stadium. Wood failed to retire a batter in game one (one Yankee reached first after a dropped third strike) as the Yanks scored eight runs in the first inning (six charged to Wood) en route to a 12–2 victory. In game two, Wood finally got his wish to start both games of a twin bill. This time he lasted 41⁄3 innings but gave up seven runs as the Sox lost again, 7–0. In doing so, Wood became the first pitcher since Jack Russell of the 1929 Red Sox to start, and lose, both games of a doubleheader.28

There were reasons for Chicago’s slump beyond Wood’s (and Bahnsen’s) poor finishes, most notably a broken leg suffered by Dick Allen on June 28. (Allen had only five more at-bats the remainder of the season.) It was a team-wide collapse, as both the team’s offense and pitching staff suffered sharp declines in production after the hot start. But the club’s starting pitchers, who had posted a 2.89 team ERA through the end of May, recorded a 4.35 mark the rest of the way, and Tanner and Sain’s frequent use of their starting pitchers on short rest began to come under increased scrutiny. For the 1973 season, Sox pitchers made 41 starts on two days’ rest or fewer, 19 by Wood. (Bahnsen made eight starts on short rest, Steve Stone seven, and Eddie Fisher four, with two going to Bart Johnson and one to Jim Kaat.) While the team posted a winning record (23–18) in those games and the starters’ ERA (3.62) in short-rest starts was again better than the club’s 4.04 mark in its other 121 starts, the slumps by Wood and Bahnsen, in particular, caused some observers to blame fatigue.

“Wilbur is not tired,”29 Tanner asserted after Wood defeated the Brewers 6–1 on August 27, for his first victory since July 29. Wood, however, made only one more start on short rest over the remainder of the year, that one on September 3, and did not pitch at all during the final week of the regular season. Asked prior to the start of the 1974 season if his eight starts on two days’ rest in 1973 had contributed to his late-season slump, Stan Bahnsen replied, “I don’t know. I think I could start on two days’ rest maybe every fourth start and it wouldn’t hurt me. But once last year I made three of those in a row. We were in a pennant race…. I figured: What have I got to lose? But maybe I lost more than I thought.”30

As the White Sox prepared for the 1974 season, Johnny Sain was no longer talking about using Wood and other Sox starters on short rest. “Our goal from the beginning has been a four-man starting rotation,” he told George Langford of the Chicago Tribune. “We wouldn’t use the two days’ rest thing if we had four solid starters. Actually, we’ve been B.S.’ing our way thru the last few years and we might have gotten away with it last year if it hadn’t been for all the injuries.”31 Over the next two seasons, Chicago’s use of its starting pitchers on short rest was greatly reduced. After making 44 starts on short rest in 1972 and 41 more in 1973, Sox starting pitchers made only six short-rest starts in 1974 and 13 in 1975. Only eight of those 19 starts were made by Wood.

Wood didn’t exactly get a light workload in 1974 or 1975, as he led the American League in games started both years. But his won-lost records were around .500 or worse (20–19 in 1974, 16–20 in 1975), and his ERA had risen every year since his 1.91 mark in 1971 (2.51, 3.46, 3.60, 4.11). Wood, though, refused to blame his decline on the frequent short-rest starts in 1971–73. “The only way that could have had a bad effect was if my arm were sore or I felt physically tired,” he told Robert Markus of the Tribune in June of 1975. “I never did.”32

Following middling seasons in 1974 (80–80) and 1975 (75–86), with attendance falling to 750,802 in 1975, White Sox team president John Allyn put the cash-strapped club on the market.33 The club was nearly sold to a Seattle-based syndicate before former Sox owner Bill Veeck stepped in with a new ownership group and purchased the club for a second time.34 Veeck replaced Chuck Tanner as Sox manager with Paul Richards, and Johnny Sain moved on as well, becoming pitching coach of the Atlanta Braves. With rare exceptions, the short-rest experiment was over for good on the South Side.

Wilbur Wood pitched for three more seasons after Tanner and Sain left the White Sox. Richards and new Sox pitching coach Ken Silvestri used Wood very conservatively early in 1976; after Wood shut out the Kansas City Royals on opening day, all but one of his next six starts were made with four or more days’ rest (the exception was a start on three days’ rest at Boston on April 18). But on May 9 at Detroit, Wood, working on a shutout in the sixth inning, took a line drive off the bat of the Tigers’ Ron LeFlore that fractured his left kneecap.35 Wood, who had posted a 2.24 ERA in 1976 up to that point, missed the remainder of the season. He returned the next year but was neither durable nor effective in 1977–78, posting a 17–18 record with a 5.11 ERA in 52 appearances (45 starts) in the two years combined.

Wood made his final career start on short rest on July 6, 1977, three days after pitching a complete-game shutout of the Minnesota Twins, and he brought back his early short-rest magic one last time with a complete-game 4–2 seven-hitter against the Seattle Mariners. But the White Sox never again started him on fewer than three days’ rest since his last start, and 26 of his 45 starts in 1977–78 were made with four or more days’ rest since his last start. Wood became a free agent after the 1978 season, but was unable to land a job with another major league team and opted to retire. “I just couldn’t do what I did before I got hurt. That took the fun out of it,” he later told the Boston Globe. 36

End of an Era

Johnny Sain spent the 1977 season with the Atlanta Braves, a team whose top starter was Phil Niekro—a knuckleballer like Wilbur Wood. The Braves used Niekro on short rest only once in 1977, and Braves’ starting pitchers made only two short-rest starts all season; Niekro, however, led the National League in games started, innings pitched and complete games, fashioning a 16–20 mark for a 101-loss team. Sain then became a coach in Atlanta’s minor league system before returning to the Braves in 1985.37 His last job as a major league pitching coach was with the 1986 Braves, when he was reunited with new Atlanta skipper Chuck Tanner. Neither the 1985 nor 1986 Braves had any pitcher starts on short rest, though Rick Mahler did lead the NL in starts both years.

Four-plus decades after his heyday as a major league pitching coach, Sain’s philosophies about starting-pitcher workloads have essentially been abandoned. According to Sam Hovland of STATS, there were only 40 short-rest starts in all of major league baseball in the 16 seasons from 2000 through 2015; Sain’s White Sox teams had more short-rest starts than that in both 1972 and 1973. Hovland’s data also show that during the 1960s and seventies, between 25 and 30 percent of all MLB starts were made with three days’ since the pitcher’s last start; from 2010 through 2015, the starts on three days’ rest fell to a minuscule 0.527 percent. Even the term “short rest” is now defined differently; in this millennium, a short-rest start is usually defined as any start with fewer than four days’ rest.

The main rationale for lightening pitchers’ workloads has been that it helps reduce the chance for injuries. That is hardly a new idea. “At the beginning of major league time, teams used their starting pitchers all game every game, without concern for long-term consequences,” Bill James wrote in 2001. “Since then, managers have tried to reduce the workloads of their top pitchers, so that they might last longer. This process began in 1876, and continues to this moment.”38 In the free-agency era, with salaries increasing and clubs often signing pitchers to long-term, multi-million dollar contracts, teams have grown increasingly conservative about how much rest to give their pitchers between starts. Table 2 tracks the percentage of major league starts since 1960 by the number of days’ rest since a pitcher’s last start. The trend is obvious: with each successive decade, pitchers have been given more rest between starts on average.

Table 2. Percentage of MLB Starts by Days’ Rest Since Last Start, 1960–2015

| DAYS’ REST | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-2 Days Since Last Start | 1.80 | 1.10 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| 3 Days Since Last Start | 29.40 | 26.40 | 9.40 | 2.50 | 0.70 | 0.27 |

| 4 Days Since Last Start | 31.10 | 38.00 | 51.00 | 55.20 | 51.20 | 47.80 |

| 5+ Days Since Last Start | 37.70 | 34.60 | 39.40 | 42.10 | 48.00 | 51.90 |

(Source: Sam Hovland, STATS LLC)

In that context, the philosophies of Johnny Sain, who had no qualms about giving pitchers very heavy workloads, seem increasingly out of step. Even pitchers who worked under Sain have been critical of him. Steve Stone, who started seven games on two days’ rest for Sain’s 1973 White Sox, commented in 2015: “I thought at the time it could have been the dumbest idea I’d ever heard and since then it becomes even dumber, because you deteriorate pitchers. If a guy isn’t a knuckleballer then you have a big problem. I didn’t think it was revolutionary. It was very nice for Wilbur. He was very happy about it because the innings piled up and so did the wins—and the losses, by the way.”

Tommy John, who pitched for Sain’s White Sox in 1970 and 1971 and was a teammate of Tom Bradley, told SB Nation in 2011: “[Chuck Tanner] and Johnny Sain were big on pitching on two days’ rest, three days’ rest, and he had Tom Bradley—Bradley could pitch. God, that son-of-a-gun could throw the ball … they rode him right into the river, man. And Bradley, I thought, was never the same pitcher after that first year….”39 Bradley’s post-White Sox pitching record seems to support John’s criticism. The White Sox traded Bradley to the San Francisco Giants for Ken Henderson and Steve Stone after the 1972 season, in which Bradley had started 40 games (including eight starts on two days’ rest), posting a 15–14 record with a 2.98 ERA. Over the remainder of his career, Bradley started only 61 more games, going 23–26 with a 4.56 ERA. Bradley ultimately suffered a torn rotator cuff and threw his last major-league pitch at age 28.40

But while Sain undoubtedly pushed the envelope in working Wood and other pitchers with great frequency, he was hardly alone during that era. To cite one example, there were 22 instances of a pitcher working 325 or more innings during the 12-season period from 1968 through 1979. In all the other years of the expansion era (since 1961) before and since that 12-year period, only one other pitcher had a 325-inning season: Sandy Koufax in 1965.

The 1960s and 1970s—Johnny Sain’s primary years as a major-league pitching coach—also featured:

- Mickey Lolich, who was anything but a knuckleballer, starting 45 games, throwing 29 complete games and pitching 376 innings in 1971.

- Seasons featuring 30 complete games from Juan Marichal (1968), Fergie Jenkins (1971), Steve Carlton (1972), and Catfish Hunter (1975).

- Nolan Ryan’s 1974 season, in which he recorded 367 strikeouts, 202 walks, 26 complete games, and 3322⁄3 innings pitched.

- Mike Marshall’s 106 games pitched and 2081⁄3 relief innings in 1974.

Table 3: Most Career Starts with 2 or Fewer Days’ Rest Since Last Start, 1914–2015

| PITCHER | YEARS | STARTS | W-L | TEAM W-L | ERA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pete Alexander | 1914-28 | 72 | 43-22 | 47-24 | 2.25 |

| Wilbur Wood | 1971-77 | 70 | 36-27 | 42-28 | 2.71 |

| Eppa Rixey | 1914-29 | 57 | 27-21 | 32-24 | 3.30 |

| Bobo Newsom | 1934-46 | 56 | 20-29 | 22-34 | 4.42 |

| Burleigh Grimes | 1916-32 | 54 | 29-22 | 30-23 | 2.93 |

| Red Faber | 1914-31 | 53 | 30-16 | 35-17 | 2.98 |

| Lee Meadows | 1915-27 | 52 | 17-26 | 24-28 | 3.39 |

| Urban Shocker | 1918-27 | 52 | 27-16 | 33-18 | 3.40 |

| Hippo Vaughn | 1914-21 | 51 | 34-12 | 36-14 | 1.93 |

| Dick Rudolph | 1914-23 | 48 | 28-12 | 30-15 | 2.04 |

(Source: Sam Hovland, STATS LLC. Tie Games not counted in Team W–L)

It was a different game, without a doubt. In that context, Johnny Sain wasn’t that much of an outlier in preaching that a pitcher could stand a heavy workload.

Wilbur Wood was definitely an outlier, and Table 3 puts his short-rest workload into context. Did all that work eventually reduce his effectiveness, and perhaps shorten his career? That is certainly an arguable point, but Wood never complained and never questioned what Chuck Tanner and Johnny Sain were asking him to do. “You know, it’s comical,” he told Robert Markus when the losses were starting to pile up late in 1973. “Guys come here and ask the exact opposite of what they asked in May. Then they wanted to know if I could win 40. Now they ask me if I’m going to lose 20. And I say the same thing to them that I said then.”

And what was that? “I hope I can win the next one.”41

DON ZMINDA has worked for STATS LLC since 1990, first as Director of Publications and now as the company’s Director of Research for sports broadcasts. He has co-authored or edited many baseball books, including the annual “STATS Baseball Scoreboard” (1990–2001) and the SABR BioProject publication “Go-Go to Glory: The 1959 Chicago White Sox.” A Chicago native, Don is a graduate of Northwestern University (BS Journalism, 1970) and lives in Los Angeles with his wife Sharon.

Notes

1. To clarify our terms, “days’ rest” in this article refers to the number of days off between appearances. A pitcher who pitches a game on Sunday and another on Wednesday is working on two days’ rest; if his next appearance is on Friday, he would be pitching on four days’ rest.

2. Tyler Kepner, “Madison Bumgarner Rises to the Moment, and Jaws Drop,” New York Times, October 30, 2014.

3. Another point of clarification: when the article refers to days’ rest between starts, any intervening relief appearances are not considered. So if a pitcher starts a game on Sunday, makes a relief appearance on Wednesday and then starts again on Friday, the study considers him to be working on four days’ rest between starts the same as a pitcher who made no intervening relief appearances.

4. Alexander’s major-league career began in 1911, but this article utilized the Retrosheet and STATS LLC MLB database, which includes player and team day-by-day data since 1914. All data for this article on MLB pitchers working on two days’ rest or fewer since their last start were provided by STATS LLC programmers Sam Hovland and Jacob Jaffe.

5. E-mail from Jim Kaat, May 4, 2015.

6. Jan Finkel, “Johnny Sain,” SABR BioProject, accessed May 8, 2015.

7. Retrosheet.org data and daily logs.

8. Finkel.

9. Finkel.

10. Telephone interview with Jim Kaat, May 8, 2015.

11. Finkel.

12. Finkel.

13. Finkel.

14. Gregory H. Wolf, “Wilbur Wood,” SABR BioProject, accessed May 8, 2015.

15. Wolf.

16. Wolf.

17. Wolf.

18. Rich Thompson, “Time Was Right for Wood,” Boston Herald, May 28, 1989.

19. George Langford, “Still More Work for Wilbur,” Chicago Tribune, August 31, 1971.

20. Pat Jordan, The Suitors of Spring (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1973), 209.

21. Langford, “Still More Work for Wilbur.”

22. Jerome Holtzman, “Iron-Man Wood Has Goal—Wants to Pitch a Twin Bill,” The Sporting News, August 7, 1971.

23. David Condon, “In the Wake of the News,” Chicago Tribune, March 12, 1972.

24. STATS LLC data, programming by Sam Hovland.

25. STATS LLC data, programming by Sam Hovland.

26. George Langford, “More Work? Really It Works!” Chicago Tribune, June 2, 1972.

27. E-mail from Jacob Jaffe of STATS LLC, May 7, 2015.

28. Historical data on pitchers’ starting doubleheaders courtesy of STATS LLC.

29. George Langford, “Wood posts 21st, 6–1,” Chicago Tribune, August 28, 1973.

30. George Langford, “Bahnsen is not unhappy over losing arbitration,” Chicago Tribune, March 1, 1974.

31. George Langford, “Gopher balls bugged Fergie,” Chicago Tribune, March 24, 1974.

32. Robert Markus, “Sox’ Wood not worried about mound problems,” Chicago Tribune, June 11, 1975.

33. Richard C. Lindberg, Total White Sox (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2006), 86.

34. John Snyder, White Sox Journal (New York: Clerisy Press, 2009), 438–39.

35. Wolf.

36. Elizabeth Karagianis, Boston Globe, April 27, 1985.

37. Finkel.

38. Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001), 866.

39. Jim Margalus, “Talking White Sox history with Tommy John,” SB Nation South Side Sox, June 24, 2011 (https://www.southsidesox.com/2011/6/24/2241067/talking-white-sox-history-with-tommy-john)

40. John Gabcik, “Tom Bradley,” SABR BioProject, accessed May 8, 2015.

41. Robert Markus, “Wilbur drinks his beer and thinks,” Chicago Tribune, August 29, 1973.