Yanet Moreno, the First Woman Umpire in Any Country’s Major League

This article was written by Reynaldo Cruz Díaz

This article was published in The SABR Book of Umpires and Umpiring (2017)

Walking into the old-school-like surroundings of Estadio Changa Mederos in Havana’s Ciudad Deportiva and running into umpire Yanet Moreno Mendinueta is an interesting experience in itself.1 Off the field, the short and smiling umpire lacks the serious and stern look that she displays while wearing the black-and-blue outfit and calling the shots either behind the plate or at third base. At 43 (born on November 9, 1973, in Luyanó, Havana), she has 17 years of experience and 14 National Series seasons (13 of them as a regular umpire and one as a substitute) under her belt.

Everyone seems to know Yanet and love her, whether players, managers, or her peers, and they all greet her with respect and affection. With three siblings (two brothers and a sister), she is without question the most sui generis member of her family and perhaps one of the most appealing people in all of baseball.

Her resolve on the field, which turns into a constant smile off the field, has made her feel admired by everyone, including the overdemanding Víctor Mesa (manager of Matanzas), who, she says, has asked for her to be the home-plate umpire because “I like the way she handles the strike zone.” Even with the microphone in front of her and an arsenal of questions in store, she still keeps her poise and humor, and answers with the same care and calmness with which she calls a runner safe or out at third base.

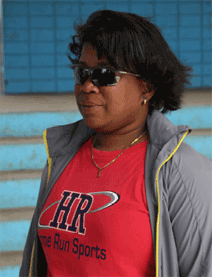

Yanet Moreno, Havana 2017.

When and how did you get interested in baseball?

I would say basically since I was born. My father used to live just behind right field in Estadio del Cerro and when I was in the first two years of my life it was very difficult for me to fall asleep, so my father used to take me there, with a feeding bottle of milk, and I would fall asleep in the game, in the middle of the crowd. Afterwards, you know, he didn’t want me to be in the ballfield, but it was he who first got me into baseball, and then there was no way to take me out of the ballpark.

Did you play baseball at any stage during your childhood?

I started as a child, playing with the boys from the neighborhood. My father would lecture me, and even ground me when he caught me red-handed, because he didn’t want people to say that I was a tomboy. I would tell the boys, “Guys, if you see that my father is coming, let me know so I can hide. Don’t narc on me!” But they were just kids, and it happened that when my father was coming, driving the car, they would tell me:“Yanet! Your father’s coming!” and I would run and hide (chuckles). But then there was always someone who would say: “Yanet, come on you’re up!” and then my father would know that I was playing (chuckles).

When did you decide to become an umpire?

For several years, up to around 1997, I was a member of the Havana softball team, because we didn’t yet have women’s baseball. I was included in three pre-rosters of the Cuban National Softball Team, until I decided not to play softball anymore, because I didn’t see myself as fully accomplished. When women’s baseball started in 1998, I switched to baseball. I was the number three hitter of the Havana team, playing second base. But as a “new” sport, there were limitations. You could not be above 25 years old, and I was approaching that age. They told me that since I was that close, when the game fully developed in Cuba I was going to be well above the age limit.

However, since I had already become a national softball umpire, commissioner Margarita Malleta told me that since I liked baseball and being in the ballfield so much, it was a good idea for me to become a baseball umpire. That way, I would be able to stay on the field. I agreed and took a provincial course, which enabled me to go to the zonal [regional] course, due to my good grades. I placed in the top five in the Western Zone, and made the grade among the 20 students that were going to attend the national school.

I spent three years at Villa Clara, the regular venue for the national school. During those three years we got qualified to be umpires at any level or category, working with the youngest kids or in the National Series, the top league. I ranked second at school and made it to the National Series as a substitute.

Were there umpires whose example you followed?

Before I started with the idea of umpiring, I looked at umpires as an athlete did, not as role models. But when I started umpiring, I had an inspiring guide in the late Felipe Casañas; he took me under his wing when I was basically a child in umpiring terms, and it was near him that I took my first steps. When I started observing umpires during the National Series, I took special notice of César Valdés, and I owe a lot to him: he didn’t see the fact that I was a woman as a shortcoming; instead, he saw that I was a capable umpire who could work in the Cuban National Series.

How was the level of acceptance?

At first, they saw me as a freak. They would say, “This woman is crazy!” “What is she doing on the field surrounded by men?” “She won’t be able to handle it!” But when they saw me work and they saw how serious I was about my job, they said, “Okay, this girl does have a chance! She can make it!” and then everyone started helping me and encouraging me to be better each day, and that worked out pretty well for me. When they saw that I had no fear of taking the field, whether the stands were packed or empty, they gave me a lot of support. They saw that as courageous, because sometimes they felt pressure themselves in such situations. My mindset was: If I can work in the Provincial Series, why can’t I work in the Zonal Championships? And if I can work in the Zonal Championship, why can’t I work in the National Games in all categories? And so on, until I took the challenge. It was like climbing a ladder, from the youngest kids to the Junior Championships, Development Leagues, and then the National Series.

Do you remember your first game in the National Series?

My first game in the National Series was in Villa Clara, as a third-base umpire. Villa Clara vs. the defunct Havana Metropolitanos. When I took the field, it was the first game of the season, and the stands were crowded … and everyone stood up and gave me a standing ovation. That was the province where I went to umpiring school, many fans knew me from that time. My second game was in that very ballpark … behind the plate (chuckles).

What were the first challenges you had to face as an umpire and as a female umpire?

The first challenge was to be accepted by my peers, then by the players and managers. At first, when I took the field, they looked at me in disbelief and said: “A woman on the field? What the hell is this? This is a man’s game!” but when I started working and they saw how confident I was, they used to say: “Okay, she’s a woman, but she works pretty well! At least she is strong-willed.” I made mistakes, like every umpire and every human being, and at first those mistakes were more frequent, but I stood by my calls. After that, everyone began to accept me and when they didn’t see me they asked, “Where’s the girl?”

So you established respect simply based on the seriousness of your work …

Umpiring is a very difficult job. First you have to learn the rulebook which is one of the biggest of any sport and which every year includes a lot of modifications. Then, you have to make athletes, managers, and fans believe in your calls. In order to do that, I had to work perhaps harder than any man. But working in the small categories, mainly in the 12U, you get to make calls on plays you probably won’t see in years of National Series experience. I worked a lot in those categories, and it was there that I honed my skills, so when I took on older categories, the range of mistakes narrowed, and it was then that I made people believe in me.

Tell us about the time when a US media crew came to interview you … when you found out that you were the first female umpire in a high-level league in the world.

I had no clue I was the first. I was stunned and didn’t even know how to react or what to say. When they got to the hotel where I was staying, they told me, “We had been trying to contact you because you are the only woman working in her country’s major league. Do you know you’re famous?” I had no clue. As a matter of fact, I thought there were other women working in other major leagues in the world. I had to ask them to give me a few minutes for the idea to sink in because I couldn’t believe it myself.

What has been the most difficult call you have had to make?

Well, about three National Series ago, I had a very difficult call to make. It was on National Television, Matanzas playing against Las Tunas, and Yosvani Alarcón went off to try to steal home plate. I called him safe. That year replay had come into force, and Matanzas challenged the call on the field, which was confirmed by the replay. I was sure of what I had seen, but nobody thought I had made the right call. When the replay proved me right, I got even more confident behind the plate (chuckles), and it enabled me to finish the game with a lot more confidence.

How do you feel when you make a wrong call?

Just as I am proud and confident when I make a difficult call right, the world collapses around me when I’m wrong. We umpires don’t ever want to blow a call, but sometimes poor positioning, or rushing too much, can make us blow the call. I always try to give it a little time before I decide, in order to have a smaller percentage chance of being wrong. But that’s true: When I blow the call, I don’t even want to be looked at and if I am at home, even my mom cannot talk to me.

What has been your best moment as an umpire?

My best moment was when I worked the playoffs for the first time, in the semifinals. It was the first of many postseason jobs. Also, when I went to the Women’s World Championship, and in 2015, that I went to the Pan Am Games in Toronto. I have been to three World Championships and a Pan Am Games tournament, and in all three events I have been chosen the top umpire. They don’t say so explicitly, but normally the one they choose is the one who officiates home plate in the Gold Medal Game, and that was my assignment in all three events.

What do you consider to be today’s top difficulties in Cuban umpiring?

If you had asked me two or three years ago, I would have answered differently, but today we are pleased in the sense that umpires come from abroad (mainly the World Baseball Softball Confederation) to give lectures and courses mainly on how to work in a way that we are similar to the Major League Baseball. These clinics take place twice a year, and that has helped us overcome certain doubts, mainly in terms of the strike zone. We have tried to unify the strike zone and have everyone call the low strike (which we had normally called balls), and to help us get rid of the trend of calling strikes horizontally and not vertically. We have learned that from them. Normally we would call a strike a ball going two or three inches from the plate, and that is not a strike. We have better awareness now that what we have to narrow the sides and widen in the height. Work remains to be done, though.

Are there others like you in Cuba?

There are three other girls who took the course, but they’re working exclusively on women’s baseball; they don’t work with men. I am trying to encourage them to work in the provincial leagues among males, and make them start in the low categories. I would love to see another woman as my peer in the National Series.

So, you see a future for female umpiring in Cuba?

Yes, I do. I am working very hard with female umpires in Cuba. My biggest accomplishment would be to help these three girls (who are the most advanced) get to the National Series and obtain the international level as I have.

At some point, you must have had terrible moments as an umpire. What has been your worst experience so far?

As an umpire, you suffer a lot when you blow a call, when you make a mistake. You suffer a lot when you work a ballgame and perform below the level you know you have. I believe that is what hurts an umpire the most. We also don’t like it when we have to eject someone because we have to; you can’t allow a batter to throw a bat or a helmet in contempt, and you know that you’re tossing a player needed by the team, but that it’s something you have to do because it’s in the rules.

How do you see the future of women in baseball, alongside men?

Things are very difficult in that aspect. Even though we have seen here in Cuba that women have been given many opportunities to exercise any profession, we can’t take back the fact that this is a macho country. And I think that having, for instance, four female umpires in a National Series is a little close to fiction. It could be accomplished, but it’s far from happening. Here in Havana we have female scorekeepers, but I think that getting to a point where four women got to be National Series umpires would be very difficult.

But you would love to see that?

Of course, and I’d love to be the crew chief there (chuckles).

REYNALDO CRUZ is the founder and head editor of the Cuban-based magazine Universo Béisbol, which is hosted in MLBlogs. He is a language graduate in the University of Holguin, in his hometown, and has been leading the aforementioned magazine since March 2010. A SABR member since the summer of 2014, he writes, translates, and photographs baseball and was in the first row of the Barack Obama game in Havana, shooting from the Tampa Bay Rays dugout. In spite of the rich history of Cuban baseball, his favorite player happens to be no other than Ichiro Suzuki, whom he expects to meet and interview. A retro lover, he envisions Fenway Park, Wrigley Field, Koshien Stadium, and Estadio Palmar de Junco as the can’t-miss places in baseball.

Notes

1 This interview was conducted by Reynaldo Cruz on January 11, 2017, in Changa Mederos Stadium, within the Ciudad Deportiva in Havana.