Yankee Stadium and Home Park Advantage

This article was written by Ron Selter

This article was published in 2001 Baseball Research Journal

Yankee Stadium, from its opening April 18, 1923, has had the reputation of being a good park for lefthanded batters and a sad place for righthanded batters. The fact that two of the greatest hitters of all time were lefthanded batting Yankees (Ruth and Gehrig) has contributed to this impression of Yankee Stadium as a happy hunting ground for lefty hitters. Anyone familiar with the configuration of the park, before its renovation in 1974-75, knows that the left field and left center field areas, known as Death Valley, made Yankee Stadium very tough on righthanded batters. It is also a fact that the home run data shows that lefthanded Yankee batters have consistently hit more homers at the Stadium than on the road.1

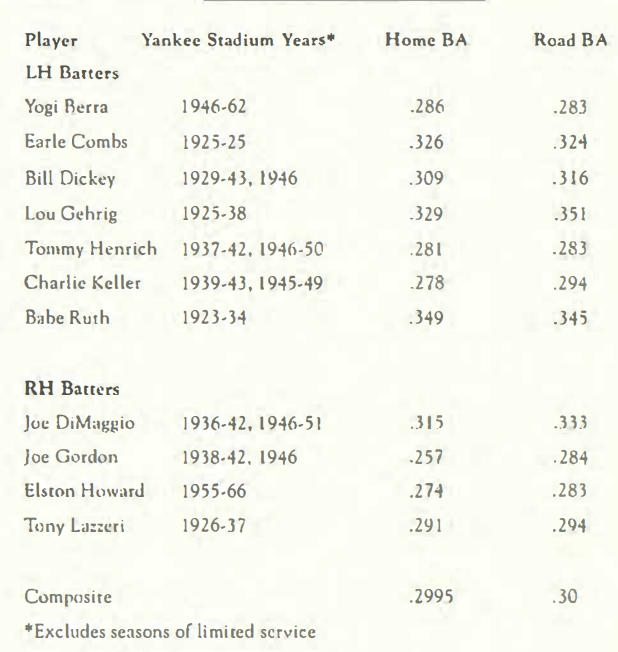

In the select world of SABR researchers, the superior road performance of Lou Gehrig has become a well-known mystery. Why did Gehrig hit .351 on the road as opposed to .329 at home?2 Home/road batting average data for Lou, six other well-known lefthanded Yankee batters, and four righthanded batters are shown at the right.

The general question concerning lefthanded batters remains: Was Yankee Stadium, compared with the other AL parks, 1923-73, a better hitter’s park as measured by batting average? A more specific research question is: To what extent can the comparative sizes of the AL ballparks in this era be used to explain the Home/road batting performances of Yankee lefthanded and righthanded hitters.

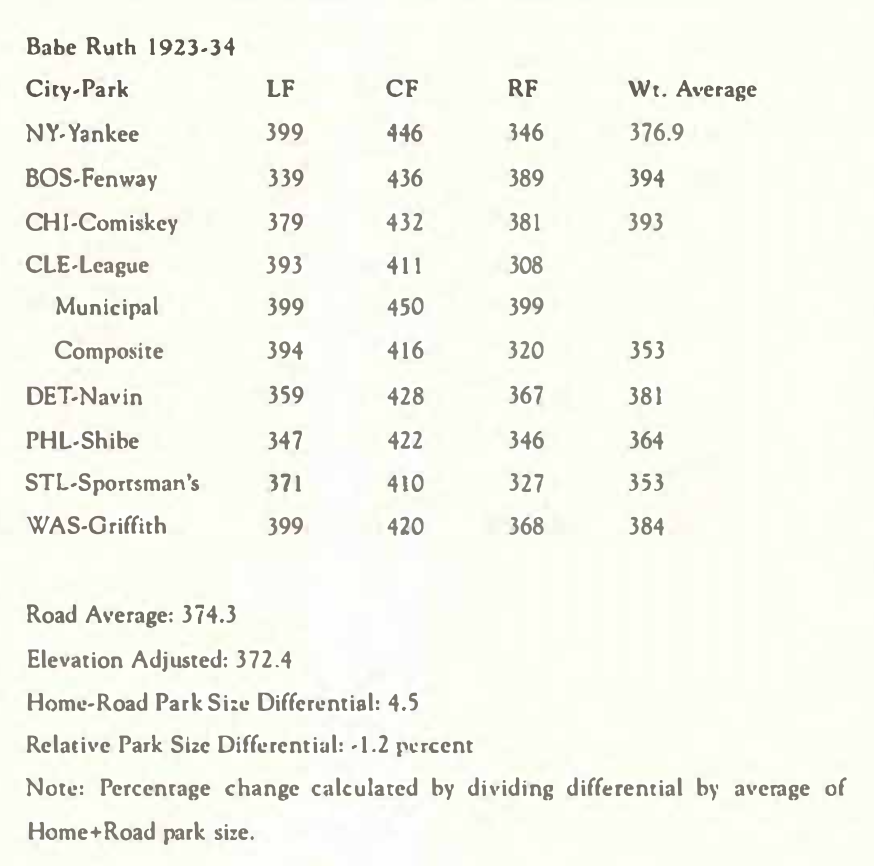

I used the following approach. I determined the average fence distances for left field, center field, and right field in Yankee Stadium during the tenure of each of the batters below. For the same time periods, I determined the average fence distances of each field of each of the batters’ road ballparks. I then derived a weighted average composite outfield distances by weighting the fields. For Ruth, I used actual 1927 data on the distribution of hits and putouts: 13 percent LF, 24 percent CF, 63 percent RF. I also used the 1927 data for Gehrig, “who did not pull the ball as much as Ruth. ” 3 Results were: 19 percent LF, 33 percent CF, 48 percent RF).4 For all other lefthanded batters, I used the distribution 50 percent RF, 25 percent CF, 25 percent RF. For the righthanded hitters, I assumed 50 percent LF, 25 percent CF, 25 percent RF).

I computed the average park size by weighting equally each season of a player’s Yankee career (excluding noticeably less-than-full seasons like Gehrig’s 1924 and 1939). The average for the road ballparks for each player was the unweighted average of the road ballpark’s average distances. For Cleveland, l derived a composite of League Park and Municipal Stadium based on the number of Yankee games at each park for each season when both parks were in use (1932-1946). I adjusted the average road park size for the elevation difference between New York and the average elevation of the road parks. This reduced the road average park size by 0.5 percent.

As an illustration, the park size data (in feet before elevation adjustment) for Babe Ruth are shown below:

Based on a study of National League home and road batting average against Philadelphia pitching in the in the 1930s (presented at SABR 30), I estimated the park size batting average coefficient to be -1.046. Thus a park with ten percent deeper fences would, all other factors held constant, reduce batting average by 10.46 percent. I used this coefficient to estimate road batting average for the differential park sizes. For each batter listed above, I used the home average in conjunction with the park size differential to predict road average. This procedure has implicit in it the assumption (only temporary) that only park size affects the relationship between home and road batting averages.

As measured by batting average, Yankee Stadium in the 1923-66 era was not a hitters park for either righthanded or lefthanded batters. The use of park size as an explanatory variable over-corrects in the estimation of road batting average. This suggests there is an inherent home park advantage even for identical home and road park sizes. The data show an unexplained variance of +1.2 percent for lefthanded batters and +0.6 percent for righthanded batters. This unexplained variance may reflect non-quantified park differences, such as hitting background or prevailing winds. However, I believe that the unexplained variance, which averages + 1.1 percent, is inherent home park advantage. It translates to three points of batting average.

Notes

1. Berra, Combs, Dickey, Gehrig, Henrich, Keller and Ruth, all lefthanded batting Yankees, had more home runs at home than on the road. Home Run Encyclopedia, by Bob McConnell and David Vincent.

2. “Home Park Effects on Performance in the American League,” by Pete Palmer, Baseball Research Journal, 1978.

3. Ibid.

4. Retrosheet data supplied by SABR’s David Vincent.