Yankee Stadium: The House That Ruth (and Unitas) Built!

This article was written by Michael Gibbons

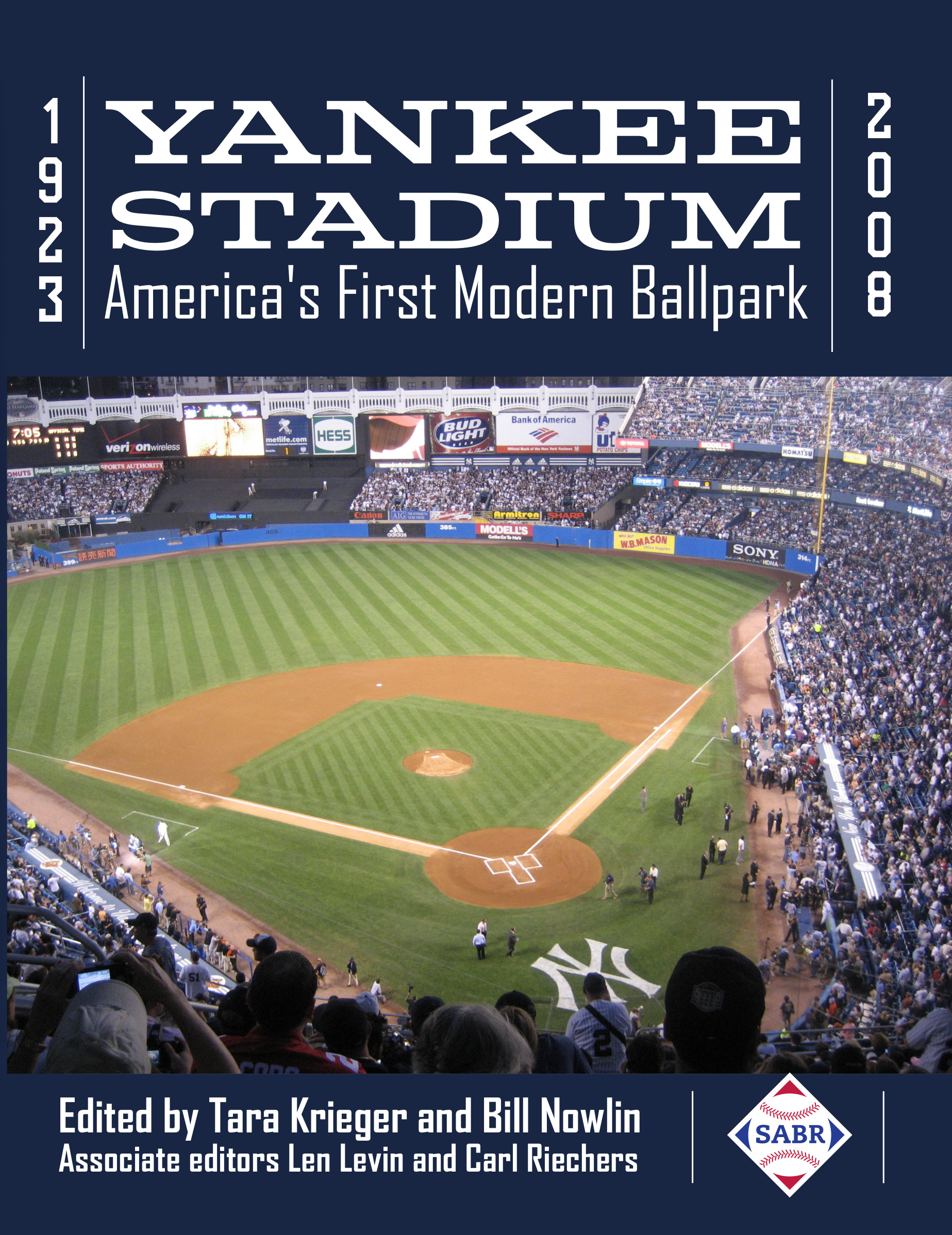

This article was published in Yankee Stadium 1923-2008: America’s First Modern Ballpark

In my 40 years working at the Babe Ruth Birthplace Museum in Baltimore, my primary focus has been preserving and celebrating the life and legacy of George Herman “Babe” Ruth. But during my tenure, the museum also expanded its mission to chronicle the rich heritage of area sports, including serving as the official archives of the Baltimore Colts. Certainly Ruth, but also those Colts, have contributed to the unique history of Yankee Stadium.

In my 40 years working at the Babe Ruth Birthplace Museum in Baltimore, my primary focus has been preserving and celebrating the life and legacy of George Herman “Babe” Ruth. But during my tenure, the museum also expanded its mission to chronicle the rich heritage of area sports, including serving as the official archives of the Baltimore Colts. Certainly Ruth, but also those Colts, have contributed to the unique history of Yankee Stadium.

What follows, then, is an offering of firsthand perspectives from the museum’s archives that contribute to Ruth’s profound impact on Yankee Stadium, plus reflections on the 1958 NFL title game, Colts vs. Giants, the “Greatest Game ever Played” in NFL history … and, perhaps in the history of Yankee Stadium as well.

* * *

Babe Ruth came to the Yankees in 1920, when his soaring popularity produced record numbers at the Polo Grounds turnstiles, overflow numbers that led to the warp-speed construction of Yankee Stadium, and its opening game on April 18, 1923. In a 1997 interview, Little Ray Kelly, an unlikely eyewitness, remembered that game … and that year, like yesterday.

Ray, you see, was Babe Ruth’s official “mascot,” a role he assumed starting in 1921 that carried through 11 seasons. Little Ray remembered playing catch with his dad along Riverside Drive as Ruth drove home after a game at the Polo Grounds. Out of habit, Babe stopped to watch the father and son’s back-and-forth, and was so taken by the exchange that he invited them to be his guests at next day’s game. In the clubhouse after the game, Ruth asked Ray’s father if Little Ray could be his personal mascot, and thus began a chapter in the young boy’s story that would generate profound, lasting memories.

Ray said the mascot idea was at first “just a PR thing” for the Babe, but that it quickly evolved into a “real game job” and a special relationship between the feisty youngster and his superstar sponsor. Ray did not travel with the Yankees, but had a steady presence for many of the Yankees’ home games. In recalling that 1923 inaugural, Ray said Ruth not only jumped with joy after clouting the first home run ever in the House that Ruth Built, he also started the practice of consuming a game-day six-pack, “a couple of dogs at a time … up to six … plus soda-pop,” which Ray would dutifully fetch.1

Ray also remembered that season’s World Series, Yankees versus Giants, won by the Yankees four games to two. Ray recalled that the Babe cracked three homers, but that future Yankees manager Casey Stengel had the winning hits in both of the Giants’ victories, which were at Yankee Stadium. His inside-the-park homer provided a one-run margin of victory in Game One, and his drive into the right-field bleachers gave John McGraw’s team a 1-0 win in Game Three. Not to be outdone by Casey’s bat, Ruth hit .368 with three homers and eight RBIs to lead the Pinstripers.2

* * *

Babe Ruth’s 60th home run, launched September 30, 1927, is one of the most chronicled moments in Yankee Stadium history. But the museum’s archives take us back to the day before, September 29, and home run number 59. To get there, let me propel you forward to May 1995, and the unveiling of the Babe Ruth statue at Oriole Park at Camden Yards, one of several special events the museum planned to commemorate Ruth’s 100th birthday. A very prominent guest at the unveiling was Paul Hopkins, a former pitcher with the Washington Senators, who made his big-league debut at Yankee Stadium on – you guessed it – September 29, 1927.3

Paul told me he remembered warming in the fourth inning. “I was very excited, because I was making my first appearance, and it was at Yankee Stadium. When I came in to start the fifth, I walked through the outfield grass and took the mound. I didn’t run.” Hopkins’ inaugural proved more than daunting, even for a rookie, as the Yankees loaded the bases with one out. Next up was Babe Ruth, who minced his way into the batter’s box. Hopkins noted that veteran Washington catcher Muddy Ruel called for a sequence of curveballs, and when the count ran to 3-and-2, Ruel told the rookie to throw a “slow curve,” which Hopkins did. Paul said the pitch was so slow that Ruth all but double-clutched, and then smacked the ball high and deep into the right-field stands. A grand slam! Welcome to the bigs, rookie!

After the game Hopkins grabbed a brand-new baseball and headed to the Yankees clubhouse. New York manager Miller Huggins stopped him short, but when Hopkins explained his mission, Huggins sent someone to get the ball signed. Ruth autographed the ball, dated it, and wrote “59th home run.” And Paul Hopkins had the most significant memento of his major-league career. But when the Senators got back to Washington, the team doctor’s 10-year-old son asked for the ball, and Paul gave it up. He said he had no idea what happened to the ball after that and could not imagine what the cash value might have been that day we talked at Camden Yards in 1995.

* * *

In 1946 Ruth was hired by General Motors to speak at area high schools. Future Baseball Hall of Fame broadcasting award winner Mel Allen, fresh off a stint in the Army, was hired by the Yankees to accompany Ruth, and to serve as emcee for the promotional visits. “Babe drove his Cadillac and did most of the talking,” Allen recalled. “I listened.” A year later, on April 27, 1947, Mel introduced the failing slugger on Babe Ruth Day at Yankee Stadium. Knowing that Ruth’s throat was wracked with the cancer that would take his life a little more than a year later, Allen asked the Babe if he wanted to speak to the crowd. Ruth answered, “I must,” and went on to deliver one of the most inspirational addresses in the history of our national pastime. “The only real game, I think, in the world, baseball,” the Bambino whispered.4

Allen joked that the Yankees forgot to retire Babe’s number 3 that day, and so brought him back the following April to officially retire his number as the team celebrated the 25th anniversary of Yankee Stadium, “The House that Ruth Built.”

* * *

On August 16, 1948, Babe Ruth succumbed to cancer. His body lay in state at Yankee Stadium over the next two days, as more than 100,000 mourners paid a final tribute to their fallen hero. Among the throngs was Frankie Haggerty, a Danvers, Massachusetts, youngster who had written to Ruth when Brother Gilbert, Ruth’s Xaverian mentor at St. Mary’s Industrial School, passed away on October 19, 1947. Like most American kids, Frankie was aware of Babe’s health struggles and asked if he could “stand in” for the Babe at Brother Gilbert’s funeral. On October 21, Ruth telegrammed Frankie: “I will be most grateful to you – but will feel I am there through your gracious gesture to go in my place.” Ruth arranged transportation for Frankie to and from the funeral at St. Peter’s Church in Lowell, Massachusetts, on October 22. Frank Haggerty walked down the aisle and “did not cry.” Local papers reported that Frank thus became one of the few people in history to pinch-hit for Babe Ruth.5

As Frankie Haggerty approached Ruth’s casket at Yankee Stadium 10 months later, reporters asked the youngster to pose next to the man he stood for the previous autumn, and to show a little emotion. The photo in the next day’s papers captured Frankie looking down on Ruth and wiping a tear from his eye. Years later, Haggerty moved to Baltimore and donated his Babe Ruth scrapbook, replete with original telegrams and news clippings, to the Babe Ruth Museum. He also shared that the famous wiping the tear photo … was staged.

* * *

On December 28, 1958, Yankee Stadium hosted what quickly became known as “The Greatest Game Ever Played,” as the Baltimore Colts traveled to New York to challenge the Giants for the NFL championship. The game has withstood the test of time, mostly because of its trailblazing on-field exploits, with Colts quarterback John Unitas leading his team to a game-tying field goal in the final seconds of regulation (the genesis of the two-minute drill) and then detaching fullback Alan “The Horse” Ameche into the New York end zone for the winning score in pro football’s first-ever sudden-death overtime. That game, with all the high drama of a New York Times best seller and played before a national television audience, put the NFL on the road to sports dominance. It’s why Baltimoreans refer to Unitas as the “Babe Ruth” of the National Football League. His performance was so superior, so “Ruthian.”

My perspective is more about what occurred behind the scenes than on the field. Here’s some background: On November 10, 1928, Notre Dame was playing favored Army at Yankee Stadium. The teams played to a scoreless tie through the first half, and when the Fighting Irish gathered in the visiting locker room, coach Knute Rockne delivered his famous “Win one for the Gipper” speech, which inspired his chargers to a 12-6 win over the Black Knights in what turned out to be Rockne’s worst season ever, with his team suffering through a 5-4 campaign.

Thirty years later, Colts coach Weeb Ewbank and his squad filled that same Yankee Stadium visitors locker room and, on the spur of the moment, Ewbank delivered a pregame talk that would have made Rockne proud. Of the 35 players suited for the game, he noted that 14 had been released outright by other teams, that seven were free agents, six came via trades, and one, Big Daddy Lipscomb, had been let go by the Rams and claimed off waivers for $100. He looked at John Unitas and said, “Pittsburgh didn’t want you, but we picked you off the sandlots.” To future Hall of Fame flanker Lenny Moore: “The idea was presented we might have a hard time getting you to practice.”6

Coach Ewbank didn’t mention every player, but they all got the message … that other teams didn’t think too highly of them. Now they could show the football world what they were made of. Obviously, the speech worked.

Giants announcer Chris Schenkel and Baltimore’s Chuck Thompson, the voice of the Colts until they left Baltimore for Indianapolis after the ’83 season, had been assigned to broadcast the game for CBS Television. Because broadcasting NFL title games was a relatively new venture, there was nothing “routine” about the telecasting process. So, as Thompson recalled, he and Schenkel went to Commissioner Bert Bell’s Manhattan office the day before the game to determine who would call play-by-play for each half. Bell flipped a coin, Schenkel won, and naturally chose the second half.7

When the game wound up in a tie at the end of regulation, Chuck naturally was in line to call the overtime period. Losing that coin toss would prove to be a career-altering luck of the draw! Thompson also recalled urging CBS to pull back on the closeups, especially after John Unitas dislocated a finger and trainer Charlie Winner pulled it straight. “Unitas,” Thompson mused, “did not blink.”

In 1994 we interviewed the Yankees’ venerable public-address announcer, Bob Sheppard, who had been at the microphone to call the ’58 thriller. Bob said he felt the Colts were the better team that day, and that the Giants were lucky to have kept the score so close. On the Colts’ drive to tie the game at the end of regulation, Sheppard recalled, “All I can remember saying was, ‘Pass thrown by Unitas, complete to Berry,’ over and over again.”8

And finally, on that last drive in the fourth quarter, with Sheppard repeating, “Unitas to Berry,” kicker Steve Myhra’s field goal to send the game into overtime offers another off-the-field glimpse from that day. As the ball fluttered through the uprights, it headed in the direction of the Baltimore Colts Marching Band, seated just beyond the end zone. The ball was caught by honor guard member George Schaefer, who curled into a fetal position to protect himself and his newly found pigskin. New York fans piled on, attempting to usurp George’s prize, and that prompted Colts band members to jump to the defense of their musical mate. New York police pounded their way in to disrupt the melee. Meanwhile, Schaefer, at the bottom of the scrum, rolled the ball to drummer Dan O’Toole, who punched a hole in his drumhead and put the ball inside. And that’s how the Myhra ball made it successfully out of Yankee Stadium.9 Years later, the museum displayed the ball … and the drum … as part of a 50th anniversary exhibit on the ’58 championship game!

* * *

From George Ruth to John Unitas, Baltimore has served up two critical building blocks to the foundation of the original Yankee Stadium, the most historic sporting venue the world has ever known.

MICHAEL GIBBONS served as executive director of the Babe Ruth Birthplace and Museum from 1983 to 2017 and has continued working with the organization as director emeritus/historian. During his tenure, the museum’s mission expanded to include Baltimore’s Orioles, Colts, and Ravens, the Maryland Terrapins, and local athletes including Michael Phelps, Carmelo Anthony, and Kimmie Meissner. He developed Sports Legends Museum at Camden Yards to house the museum’s expansive collection of state sports memorabilia. A native Baltimorean, Gibbons earned his undergraduate degree at the University of Maryland Baltimore County and a graduate degree from Johns Hopkins University. He taught writing for 23 years at the University of Baltimore.

SOURCES

All interviews were conducted by the author. Thanks to producers Jackson Whitt and John Patti, who joined for the Mel Allen and Bob Sheppard interviews.

NOTES

1 Ray Kelly information from a September 1997 radio interview with Little Ray Kelly conducted by the author, WBAL Radio’s Gerry Sandusky, and Doug Roberts. Babe Ruth Museum audio archives #128.

2 Ray Kelly interview.

3 Interview with Paul Hopkins, May 1995. Babe Ruth Museum audio archives #41.

4 Interview with Mel Allen, June 1994. Babe Ruth Museum audio archives #89.

5 Interview with Frankie Haggerty in 2001, and with additional material from Haggerty’s scrapbook.

6 Reference to Weeb Ewbank’s pregame talk is drawn from John F. Steadman, Football’s Miracle Men (Cleveland: Pennington Press Inc., 1959), 169-171.

7 Chuck Thompson recollections from Babe Ruth Museum audio archive interview, 1997, #149B.

8 Bob Sheppard’s recollections from Babe Ruth Museum audio archives interview, 1994, #003.

9 Story about Myhra ball and the Colts Marching Band from 2008 interview with Babe Ruth Museum senior staffer John Ziemann, president of Baltimore’s Marching Ravens, formerly president of the Baltimore Colts Marching Band.