Zane Grey’s Redheaded Outfield

This article was written by Joseph Overfield

This article was published in SABR 50 at 50

This article was originally published in SABR’s The National Pastime, Winter 1985 (Vol. 4, No. 2).

Zane Grey possesses “no merit whatsoever either in style or in substance,” wrote Burton Rascoe, the brilliant but acerbic New York literary critic. And this was the view of another critic, Heywood Broun: “The substance of any two Zane Grey books could be written upon the back of a postage stamp.”

The public disagreed. According to the authorized biography of Grey written by Frank Gruber in 1970, the 85 books he wrote sold 100 million copies. Millions more saw the 100 movies based on his books.

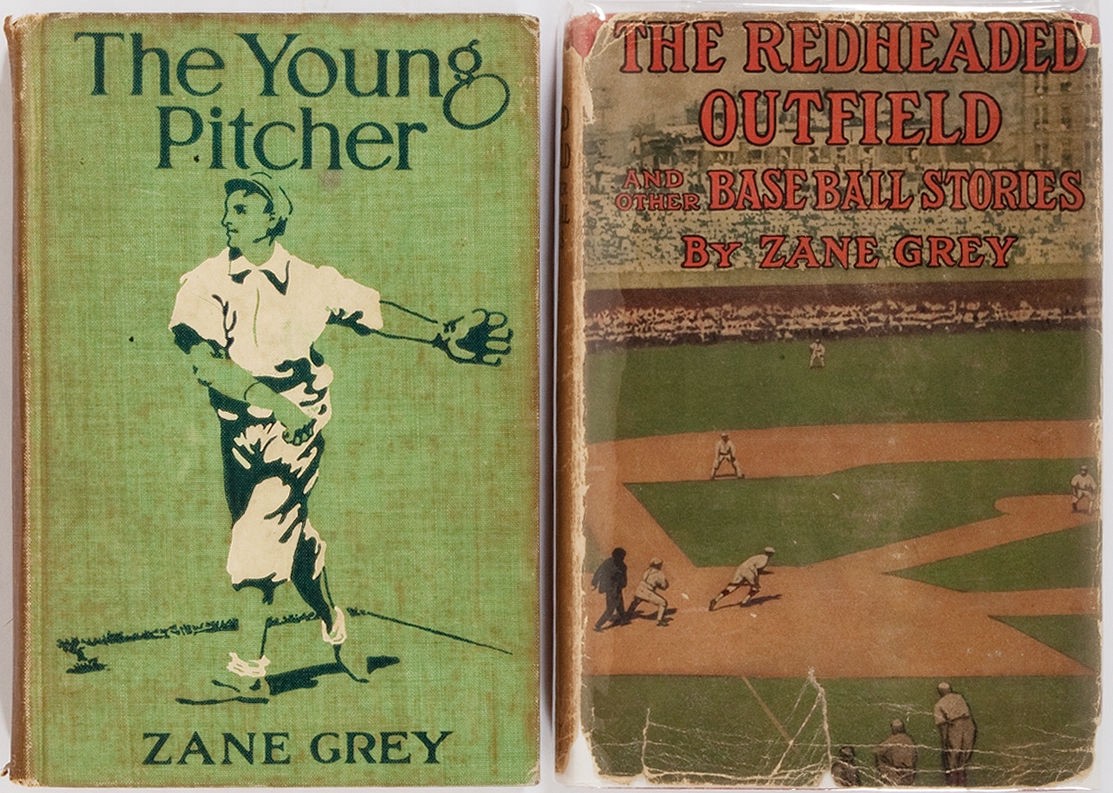

Most of Grey’s books were about the American West, but those he wrote about deep sea fishing and on his world travels were widely read as well. Often forgotten is the fact he wrote numerous baseball stories that gained wide popularity among young readers. Grey’s short story “The Redheaded Outfield” is one of the most famous and widely read baseball stories ever written. Published by the McClure Syndicate in 1915, it was reissued in 1920 along with 10 other baseball stories under the title The Redheaded Outfield and Other Stories.

It is not surprising that Grey wrote about baseball. He started to play as a youngster in Zanesville, Ohio, where he was born January 31, 1875. It has been suggested that he was forced to excel in sports to overcome the stigma of the name his mother had given him, Pearl Gray. Eventually he dropped the Pearl and assumed his middle name, Zane, and at the same time changed his surname from Gray to Grey. As a teenager he was recognized as one of Zanesville’s better young pitchers. Equally adept as a ballplayer was his younger brother, whose unusual first name, Romer, seems somewhat prophetic for one destined to attain a degree of fame as an outfielder in professional baseball.

When the Gray family moved to Columbus in 1890, the brothers’ baseball horizons broadened. Both joined the Capitols, a strong amateur nine, for whom Pearl soon became the star pitcher. A scout for the University of Pennsylvania watched him defeat Denison College of Granville, Ohio, whose star pitcher was Danny Daub, a future major leaguer. Penn offered him a baseball scholarship, and to satisfy his dentist father he decided to enter the dental school. After barely passing his entrance examinations, he began his college career in 1892. His graduation in 1896 was by the slimmest of margins.

Undistinguished as he was in the classroom, he more than made up for it on the diamond. He played college baseball for four years, first as a pitcher and then as an outfielder. In 1896 he helped Penn defeat the New York Giants in an exhibition game, and then in the last game of the season he hit a home run with one man on in the last of the ninth to defeat the University of Virginia. Helped financially by his father and by Romer, who had already started his professional baseball career, Grey set up a dental practice in New York City in 1896. Since the income from his practice was small, or possibly because he much preferred baseball to dentistry, he continued to play baseball in the succeeding summers. The entire story of Grey’s professional baseball activity is somewhat shrouded in mystery. Biographer Jean Karr writes that he played in the Eastern, Tri-State, and Michigan State Leagues, but cites no years and no cities. Gruber’s book paints another picture. He wrote: “Pearl was sorely tempted to turn professional but he knew it would be the end of his dream of becoming a writer.”

According to the Grey obituary in The Sporting News, he played for Wheeling in the Iron and Oil League in 1895, Fort Wayne of the Interstate League in 1896, and Toronto of the Eastern League in 1899. SABR members Vern Luse and Robert Hoie have uncovered some pertinent data. Luse found an item in Sporting Life, April 15, 1896, reporting that Pearl Zane Gray had signed with Jackson of the Interstate League. Hoie has found he played for Newark of the Atlantic League in 1898, batting .277 in 38 games. The haziness of his baseball career notwithstanding, his exposure to the game was such that it was only natural he should write about it. His first substantial check came from The Shortstop, published by A.C. McClurg of Chicago in 1909. Another success was The Young Pitcher, in which the author, transformed into “Ken Ward,” is the hero and brother Reddie Grey is the shortstop. A few years later he wrote “The Redheaded Outfield,” starring Red Gilbat, Reddy Clammer, and Reddie Ray of the Rochester Stars of the Eastern League.

Two of the redheads were trouble personified. “Gilbat was nutty and his average was .371. The man was a jack-o-lantern, a will-o-the-wisp, a weird, long-legged, redhaired phantom.” Clammer was a grandstand player “who made circus catches, circus stops and circus steals, always strutting, posing, talking, arguing and quarreling.” Reddie Ray, on the other hand, “was a whole game of baseball in himself, batting .400 and leading the league.” “Together,” wrote Grey, “they made up the most remarkable outfield in minor league baseball.”

The story revolves around a single crucial game between the Stars and the Providence Grays, a game in which the Stars’ manager Delaney (first name not given) flirts with apoplexy before it is over. First, Gilbat is playing ball with some kids four blocks away and is rounded up only as the game is about to start. In an early inning Clammer is forced to make a one-handed catch (a no-no in those days) because his other hand is filled with the peanuts he is munching on. Then Gilbat, enraged by some remarks about the color of his hair, leaps into the stands to battle the hecklers and is put out of the game. In the sixth Clammer crashes into the wall in making one of his circus catches and is knocked cold. “I’ll bet he’s dead,” moans Delaney. He revives but is through for the day. With no substitutes available for Gilbat or Clammer, the Stars are forced to play the last three innings with just one outfielder, Reddie Ray, “whose lithe form gave the suggestion of stored lightning.” It comes down to the last of the ninth, the bases are full, the Stars are down by three and Reddie Ray is at the plate. He smashes one to right center for an inside the park home run and victory for the Stars.

“My Gawd!” exclaimed Delaney, “wasn’t that a finish! I told you to watch them redheads.”

Such was the Redheaded Outfield in fiction. In fact, it was the outfield of the 1897 Buffalo Bisons of the Eastern League, not of the Rochester Stars. In the story Gilbat, Clammer, and Ray make up the redheaded trio; in fact, their names were Larry Gilboy, Billy Clymer, and Romer (R.C. or Reddie) Grey, the author’s younger brother. In the story the harassed manager is one Delaney; in fact, the manager was Jack Rowe, a hard-bitten veteran of the baseball wars who had been a member of the famed Big Four (with Dan Brouthers, Deacon White, and Hardie Richardson) of Buffalo’s National League days. Such a dramatic game as described by Grey was never played by the 1897 Bisons. Closest to it was a game played against Scranton on August 5 when the Bisons rallied in the last of the ninth for a comeback win. Clymer and Grey participated in the rally with hits, but the tying and winning runs were driven in by non-redheaded third baseman Ed Greminger.

In the story Grey calls it the greatest outfield ever assembled in the minor leagues; in fact, that would be stretching the truth. But who can say it was not the most unusual? People who know about such things tell us there is one chance in 19 of being a redhead, which makes the emergence of three redheads in one outfield on one minor-league team the longest of long shots.

Perhaps not the greatest, but they were good nonetheless. “Fast and sure, both in the field and at bat,” wrote a Buffalo reporter. The headline in the Express after the Bisons’ opening day win at Springfield was: “REDHEADS GREAT PLAYING!” In the game account we are told that “the redheaded outfield distinguished itself by covering every inch of ground,” and that “Gilboy stood the fans on their heads with a spectacular onehanded catch off the bat of Dan Brouthers.” In game two of the season, Bill (“Derby Day”) Clymer was the star, “catching seven balls that were labeled for hits.” On May 8 at Scranton, Gilboy made an acrobatic catch, called “far and away the best catch ever seen at Athletic Park.” After a game at Wilkes-Barre, a writer called them great, “as good as any outfield in the game,” then added: “Clymer and Gilboy were really sensational. They made some of the most startling plays ever seen in Wilkes-Barre. Both have evidently been with a circus.”

When the Bisons opened at home on May 16 against Rochester, they were in first place with an 8-3 record. The highlight of the first game was a miraculous onehanded catch by Clymer, which he topped off by doing a complete flip-flop. On Memorial Day, Clymer provided the one bright spot in what the Express described as an “execrable game” by the Bisons, by snaring a long drive off the bat of McHale of Toronto and then crashing into the fence, just as in the Grey story. According to the Express, “It was the most thrilling out seen here this season.” Clymer was applauded to the skies when he came immediately to the bat (as so often happens after a spectacular fielding play), and he responded by slashing a hit to left. Not to be outdone by Clymer and Gilboy, Reddie Grey, on June 26 in a game at Rochester, raced to right center to make a one-handed catch of a sinking liner hit by Henry Lynch. His momentum was so great that he turned head over heels after he made the catch.

And so it went all season, with visiting players and managers marveling at the play of the three redheads.

And they were far from slouches at the bat. Gilboy, while not a long-ball hitter (one triple and two home runs for the year), was a gem of consistency. He hit safely in 28 of the first 30 games and then after a couple of blanks proceeded to hit in 14 straight games. For the season he totaled 201 hits (second only to Brouthers’ 225), scored 110 runs, hit 44 doubles, stole 26 bases, and batted .350.

Reddie Grey, called by the Express writer “the perambulating suggestion of the aurora borealis,” played every inning of the Bisons’ 134 games, batting .309, with 167 hits, 29 doubles, 13 triples, and 2 home runs. In a game against Scranton in which he was the hitting star, he was, in the quaint practice of that day, presented with a bouquet of flowers as he came to the plate. He responded by doubling to left. Clymer, the most brilliant of the three in the field, was the weakest with the stick. He batted just .279 on 154 hits, but his extra-base totals were strong — 32 doubles, 5 triples, and 8 home runs. Five of his homers came in a twelve-day period beginning on August 12 and caused the Express writer to inquire: “We wonder what oculist Clymer has seen?” Clymer’s fielding average was phenomenal for those days — .969 with just 14 errors. As for the others, Grey fielded .915 and Gilboy .913.

Spurred by the redheads, the Bisons were in the pennant race most of the year, holding first place as late as August 14. A late August slump, however, saw them drop to third by the end of the month. This was where they finished, a disappointing 10 games behind first-place Syracuse and four games behind Toronto. As the team began to fade, so did the early-season euphoria. After a loss to Toronto, the Express said, “There are players goldbricking and the fans know who they are.” And then the next day, after another loss: “The infield played like a sieve. Could some players be playing for their releases?” First baseman and captain Jim Fields was abused so severely from the stands after making an error that he asked Manager Rowe for his release, which was not granted. In September, after three straight losses to Springfield, the Express writer, warming to the task, wrote: “The Eastern League is a beanbag league, just where the Bisons belong. They are playing the type of baseball that made Denmark odiferous in the days of Hamlet.”

The 1897 season, which had started on such an optimistic note, came to a merciful end on September 22 with gloom and pessimism pervading the atmosphere. Owner Jim Franklin complained that he was losing money (“This has been no Klondike for me”), the press was vitriolic, the fans were disgruntled, the Eastern League was rocky, and the Western League of Ban Johnson was casting covetous eyes on Buffalo. (Editor’s Note: Actually, Buffalo did join the Western League in 1899.)

But spring has been known to wash away the depressions of falls and winters, and so it was in Buffalo as the 1898 baseball season approached. But what of the fabled redheaded outfield of 1897? Surprisingly, it was destined for a one-year stand. Clymer, who had been with the Bisons since 1894, was the first to go, being shipped to Rochester on March 11. Five days later the Express announced: “A Chromatic Deal — Grey for White.” In an even exchange of outfielders, Reddie Grey had been sent to Toronto for Jack White. Only Gilboy remained. Not only was he coming back, but he was to get a raise, as well. Word from his home in Newcastle, Pennsylvania, was that “he had spent the winter as one of the leaders of the gay [old connotation] society.” When he arrived in Buffalo in early April, the Courier noted that “the most prominent thing on Main Street was Gilboy’s summer dawn hair, topped with a white hat.”

Billy Clymer remained in the game for many years as a player and manager, returning to Buffalo in 1901, 1913, 1914, and from 1926 to 1930. This writer recalls him clearly, as he managed the 1927 Bisons to a pennant — strutting, chest out, argumentative, flamboyant, just as Reddy Clammer had been in the Zane Grey story. Clymer’s managerial record is remarkable. He managed 23 complete seasons and parts of six others, all in the minors, compiling 2,122 wins and 1,762 losses for a percentage of .546. He won seven pennants and had an equal number of second-place finishes. Counting only the complete seasons, his record shows just three second-division finishes. He died in Philadelphia, December 26, 1936, at the age of 63. The Macmillan Encyclopedia shows he played just three major-league games, those with Philadelphia of the American Association in 1891. Reddie Grey played in the Eastern League with good success until 1903, performing for Toronto, Rochester, Worcester, and Montreal. With Rochester in 1901, he led the league in home runs with 12. In The History of the International League: Part 3, author David F. Chrisman picked him as the league’s most valuable player for that year.

According to the Macmillan Encyclopedia, Grey never played in the major leagues. This is disputed by SABR member Al Kermisch, who maintains that Grey played a game for Pittsburgh on May 28, 1903, but was confused with another Grey and therefore has not been listed as a major league player. [Editor’s Note: This situation was remedied long ago, and Reddy Grey does have his entry in the MLB Player Registers.]

Once out of baseball, he followed his father and brother into dentistry, but eventually gave it up to become his brother’s secretary, adviser, and companion on his world travels. A strong fraternal relationship existed between Romer and Zane throughout their lives. Zane never forgot that it was R.C., along with his father, who helped him financially when he was setting up his dental practice in New York and that it was R.C. who gave him encouragement and monetary assistance when he was struggling to establish himself as a writer. Zane showed his esteem for his younger brother by naming his first son Romer. R.C. died in 1934 at age 59, one year before Zane too passed on.

Little is known about the third member of the redheaded triumvirate, Lawrence Joseph Gilboy. He lasted with the Bisons only until May 27, 1898, when he was released outright because, in the words of owner Franklin, “He was worse than useless when he got on the lines.” He signed with Syracuse, played only a few days, was released, played for Utica and Palmyra of the New York State League and for Youngstown of the Interstate. There is no record that he played after 1898. It was a strange and abrupt ending to a career that had started so brilliantly. There was a note in the Express that he was entering Niagara University to study medicine. The school cannot find that he ever enrolled. Such is the story of three minor-league outfielders who would have long since been forgotten, were it not for the color of their hair.

Related link:

- A fuller account of Zane Grey’s many professional clubs may be found here at John Thorn’s Our Game blog.