Charles DeMotte, Jeremy Beer win 2020 SABR Larry Ritter Book Award

During their lifetimes, James T. Farrell and Oscar Charleston shared little in common. Farrell, an Irish American from the South Side of Chicago who embraced the American League’s White Sox, penned more than 50 novels and political works. Charleston, an African American from Indianapolis, served in the Army before employing a unique blend of speed, strength and fierce competitive drive to embark on a lengthy career in the Negro Leagues as one of the greatest players in the history of the game.

Both men came of age during and were shaped by baseball’s Deadball Era, and each is the subject of a book that shares the 2020 Larry Ritter Book Award.

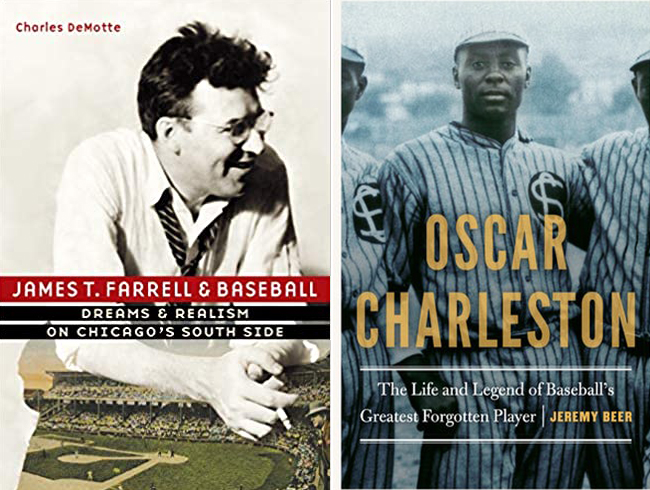

Charles DeMotte’s James T. Farrell and Baseball: Dreams and Realism on Chicago’s South Side and Jeremy Beer’s Oscar Charleston; The Life and Legend of Baseball’s Greatest Forgotten Player, both published by University of Nebraska Press, have been named co-winners by SABR’s Deadball Era Committee.

The award is granted annually by SABR’s Deadball Era Committee to the author of the best book about baseball between 1901 and 1919 published during the previous calendar year. The winner’s work must demonstrate original research or analysis, a fresh perspective, compelling thesis, impressive insight, accuracy, and clear, graceful prose.

DeMotte is an adjunct professor of sociology at the State University of New York College at Cortland. He is the author of Bat, Ball, and Bible: Baseball and Sunday Observance in New York. Beer is a founding partner at American Philanthropic in Phoenix. His work has been published in a number of national publications including the Washington Post, National Review and SABR’s Baseball Research Journal. He is the author of The Philanthropic Revolution: An Alternative History of American Charity.

Jason Novak’s Baseball Epic; Famous and Forgotten Lives of the Deadball Era (Coffee House Press), also earned consideration as a Ritter Award finalist.

The winners were selected by the Larry Ritter Book Award Committee chaired by Doug Skipper, with members Mark Dugo, David Fleitz, Ben Klein, Craig Lammers, John McMurray, and Mark Pattison. The committee released the following statements about each winning book.

On Charles DeMotte’s James T. Farrell and Baseball:

DeMotte’s crisply written James T. Farrell and Baseball offers an engaging and enlightening history of the growth of amateur, semi-pro and black baseball and its role as a social force in early 20th century Chicago. DeMotte describes the rapid expansion of organized leagues and the development of playing facilities throughout the gritty, bustling, burgeoning metropolis, at the time America’s second largest city. As baseball continued to gain popularity as a participatory sport, boys and young men ventured forth to represent their ethnically defined neighborhood-based teams, and tested their skills on and off the diamond against representatives from other neighborhoods. DeMotte suggests that these interactions with boys and young men from different and diverse backgrounds would greatly influence Farrell’s writing.

Baseball was also popular as a spectator sport in Chicago, which boasted teams in the American, National and Federal Leagues during Farrell’s youth. The Cubs and White Sox each won multiple World Series during the Deadball Era and rooting for (or against) either team served as a melting pot that transcended ethnic and racial boundaries. As a fan of the South Side team, Farrell was able to cheer for Eddie Collins and “Shoeless” Joe Jackson at nearby Comiskey Park against the likes of Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker and Babe Ruth. The White Sox won the World Series in 1917 when he was 13, but Farrell and his fellow fans were disillusioned by the Black Sox Scandal after the 1919 World Series.

DeMotte vividly demonstrates that his experience as a fan of the White Sox, his participation in baseball as a young player, and his childhood experiences on the streets of South Side Chicago, shaped Farrell’s writing. His first and most famous protagonist was Studs Lonigan, the subject of three successful novels published during the depths of the Great Depression. Studs roams the streets of the South Side, and like Farrell himself, comes of age during the last years of the Deadball Era. A fun-loving, high-spirited, kind-hearted young baseball player at the start of the series, Studs evolves into a bitter, physically and emotionally crippled man by the end of the series. In subsequent novels, Farrell often revisited baseball the South Side for inspiration, creating characters such as Danny O’Neill, a baseball-playing protagonist who frequented Comiskey Park in a five-novel series.

On Jeremy Beer’s Oscar Charleston:

Beer’s Oscar Charleston is a robust, well-researched and brilliantly written biography that illuminates the life of one of baseball’s most talented, enigmatic and previously little known figures. Rated by Bill James as the greatest Negro League Player, and the fourth best player overall behind only Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner and Willie Mays, Charleston’s legacy had been largely dimmed by time.

Beer traces Charleston’s early life and development as a baseball player in Indianapolis, his enlistment in the US Army at the age of 15, and his military service in the Philippines where he honed his blossoming baseball skills. Voluntarily discharged, Charleston joined Ben Taylor and Rube Foster as Negro League pioneers. During the final five years of the Deadball Era, in a time when black baseball leagues were transitory and movement between franchises were fluid, Charleston starred for the Indianapolis ABCs, Lincoln Stars, Chicago American Giants and Detroit Stars.

Still a young man, Charleston emerged as the Negro League’s greatest star; a fine pitcher, a fleet and strong-armed outfielder and first baseman, a punishing hitter, and a resourceful manager. He also possessed a quick and explosive temper and sometimes engaged in violence, though Beers makes a convincing case that Charleston generally managed his anger both on and off the diamond.

Charleston’s career extended well beyond the Deadball Era as he fashioned a 39-year Hall of Fame career in the Negro Leagues, seven season of winter ball in Cuba and numerous barnstorming swings. He played with and against and managed other Negro League legends including Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, Cool Papa Bell, Judy Johnson, and on occasion, against white major leaguers in exhibition games. Beers chronicles those encounters without exaggeration of hyperbole, leaving the reader to understand that Charleston would have been a Hall of Famer if only he had been welcomed into the major leagues.

Well past his prime by 1947 when Jackie Robinson broke the major league color barrier and baseball slowly started to integrate, Charleston continue to manage and mentor young players, including catcher Roy Campanella, who he recruited for the Brooklyn Dodgers in his role as major league baseball’s first African American scout. Charleston also remained involved in Negro League baseball until his untimely death at age 57 in 1954.

Although Charleston’s career took place largely after the end of the Deadball Era, Oscar Charleston earns a share of the Ritter Award because Beer has advanced our understanding of the period. He provides a depth and quality of content about a previously under-explored subject, black baseball in the Deadball Era, and provides us with a better understanding of his subject’s often complicated personal and professional life during that time and beyond.

In addition to a share of the 2020 Larry Ritter Award, Oscar Charleston has also been named winner of SABR’s Seymour Medal, the Robert Peterson Award by SABR’s Negro Leagues Committee, and Spitball Magazine’s Casey Award.

For more information on the Larry Ritter Award, including a list of previous winners, click here.

Originally published: April 28, 2020. Last Updated: May 29, 2020.