Dick Allen and the team that saved the White Sox

Editor’s note: This excerpt, which appears by permission of the author, is from SABR member Ed Gruver’s upcoming book, “October ’72.”

By Ed Gruver

His team trailing by two runs in the bottom of the ninth inning, it didn’t take Chuck Tanner long to pick a pinch-hitter.

“Okay, Dick,” the Chicago White Sox skipper said to Richie “Dick” Allen. “Go in and hit.”

It was late in the day on June 4, 1972, the second game of a doubleheader against the New York Yankees. The Sox had won the first game 6-1, Allen contributing two hits and a run scored as Chicago improved to 24-17 to stay in second place in the West, one-half game ahead of Minnesota and 3.5 games behind Oakland.

It was late in the day on June 4, 1972, the second game of a doubleheader against the New York Yankees. The Sox had won the first game 6-1, Allen contributing two hits and a run scored as Chicago improved to 24-17 to stay in second place in the West, one-half game ahead of Minnesota and 3.5 games behind Oakland.

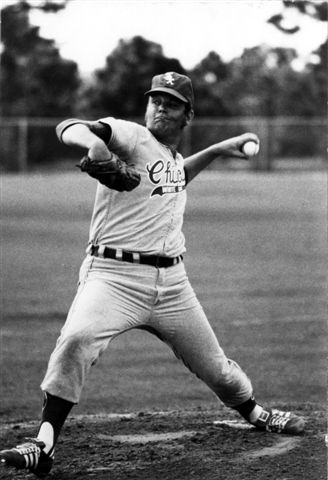

The doubleheader drew 51,904 fans to Comiskey Park and left another 8,000 hopefuls stranded on the sidewalks surrounding the jam-packed stadium. The crowd inside Comiskey was the old ballpark’s largest in 18 years, lending a festive atmosphere to the proceedings. Thousands had come to see Allen, who was in the midst of an MVP campaign that would see him hit .308 and lead the league in home runs (37), RBIs (113), walks (99), on-base percentage (.420), slugging percentage (.603) and OPS (1.023). And he did all of this while playing his home games in pitcher-friendly Comiskey Park.

Each of Allen’s homers seemed to come with a story, and June 4 provided one of his – and the Sox – more memorable moments: the “chili dog homer.”

Tanner had chosen to let Allen sit out the second game. “He’s played every inning this year,” Tanner explained, “and he deserves a rest.”

But as soon as the lineups were posted on the scoreboard – sans the Sox superstar – team owner John Allyn placed a call to his manager.

“Where,” the boss asked, “is Allen?”

Tanner’s response was unruffled.

“I’m saving him for late in the game,” he said. “I’ll send him in to pinch-hit with a couple men on base so he can hit a homer and win the game for us.”

The Yankees led 4-2 in the bottom of the ninth. Bill Melton worked a one-out walk and Mike Andrews singled to left, prompting New York manager Ralph Houk to bring in southpaw reliever Sparky Lyle.

Tanner responded by sending a batboy to the clubhouse to summon his slugger.

“I was eating a chili dog when I heard Chuck wanted me to hit,” Allen remembered. “I had chili all over my shirt so I put on a new one and a pair of pants with no underclothes.”

As Allen hefted his bat – at 40 ounces it weighed a half-pound more than those used by other sluggers his size in the early 1970s – Tanner sent Jorge Orta in to pinch-run for Andrews. When Allen was announced as a pinch-hitter, Andrews, who had been Lyle’s roommate on the Red Sox, shouted at Lyle, “Sparky, you’re in deep (crap) now!”

Allen strode to the plate, took a strike and then a ball. The next pitch is one he’ll remember the rest of his life.

“Sparky Lyle threw me a slider,” he said, “and it wound up in the seats.”

It wound up some 370 feet away in the left-field grandstand, winning the game for the White Sox, 5-4. It was the ninth walk-off home run of Allen’s career.

For the Sox and their delirious fans, it was a giddy, heady moment not seen on Chicago’s South Side since 1967. The crowd refused to leave Comiskey Park and spent the next 30 minutes after the game standing, cheering and hollering.

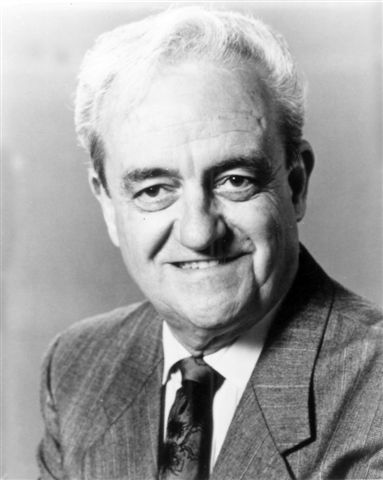

Allen called it a “memorable moment,” one of many for the White Sox that summer. Allen, Tanner, Wilbur Wood, Carlos May, Jay Johnstone, Stan Bahnsen, “Beltin’” Bill Melton, Walt “No Neck” Williams, Rich “Goose” Gossage and Terry Forster produced a season of excitement that built over the course of the summer, thanks in no small part to the enthusiastic radio calls of new Sox broadcaster Harry Caray on WTAQ/WEAW.

On May 21, the Sox trailed California 8-6 in the bottom of the ninth. With two out and two on, May dug in against reliever Alan Foster.

Caray: “There’s the pitch. … There’s a long drive. … White Sox win! … This puts the White Sox in first place in the Western Division! Holy cow, this crowd is wild! Everybody’s screaming … I’m the only calm guy in the ballpark!”

On July 23, in another Sunday doubleheader, the Sox beat the Indians in the opener at Comiskey but trailed 3-1 in the bottom of the eighth. Once again, the Sox showed a flair for the dramatic. Ed Hermann’s home run and Allen’s RBI groundout combined to tie the game, setting the stage for May’s leadoff at-bat in the ninth:

Caray: “There’s a long drive. … Way back. … It might be. … The Sox win a doubleheader! Carlos May just hit his second home run of the game!”

Eight days later, the Sox were in Minnesota’s Metropolitan Stadium for a two-game set with the Twins. Both clubs were in need of a win to keep pace with the Swingin’ A’s. The Met was a big ballpark with power alleys that seemed as wide as the Grand Canyon.

Eight days later, the Sox were in Minnesota’s Metropolitan Stadium for a two-game set with the Twins. Both clubs were in need of a win to keep pace with the Swingin’ A’s. The Met was a big ballpark with power alleys that seemed as wide as the Grand Canyon.

Assisted by physical and judgmental errors by Twins center fielder Bobby Darwin, Allen became just the second man in major league history to that point to hit two inside-the-park home runs in the same game. Both homers came off future Hall of Famer Bert Blyleven. In the top of the first inning Allen roped a drive to right-center. As Darwin took his angle on the ball, his feet slipped out from under him, the ball took a strange hop over him and rolled to the fence. Allen, Pat Kelly and Luis Alvarado scored for a quick 3-0 lead.

Jack (“Let’s go the races!”) Drees made the call on WFLD, the Sox’ television network:

“He’s got this one, lined to center, Darwin over and he falls down! Ball bounces over him, goes back to the screen, two runs will score. … Allen is coming to third, they’re waving him in! C’mon Dick, get an inside-the-park home run. … He’s got it!”

In the fifth, Allen followed Alvarado’s RBI single with a sinking liner to left-center. Darwin tried to make a shoestring catch but the ball got by him. Allen, who was quick as well as strong and had 19 steals on the season, raced around the bases for his major league record-tying second inside-the-park homer in a single game. Chicago romped 8-1 to split the series.

It wasn’t just that Allen was thrilling Sox fans with a level of baseball many on the South Side had never seen before, it was the way he was doing it that gripped their imagination. Almost one month after his record-tying afternoon in Minnesota, Allen made history again.

On August 23, in the seventh inning of a tight game, Allen unloaded on a 2-0 offering from the Yankees’ Lindy McDaniel and sent it soaring into the center field bleachers directly under the Comiskey Park scoreboard. Caray, who was broadcasting the game from that area as was his custom for Wednesday afternoon games, came close to catching the ball in his famous fishing net, which he kept for just such an occasion. Fans who were in Comiskey that day remember the shirt-sleeved crowd being sent into a state of shock and awe. Caray was stunned by Allen’s blast, which cleared a wall 445 feet from home plate and highlighted a 5-2 win.

Allen had a majestic quality about him and his power was prodigious. His sky-scraping homers exceeded even the most distant reaches of stadiums and sometimes even their rooftops. He was the “Chisox Colossus” to some, the “Wampum Walloper” to others. The late Hall of Fame baseball writer and historian Jerome Holtzman called Allen “as gifted a ballplayer as there ever was in the major leagues.” There has been a long-running debate whether Allen belongs in baseball’s Hall of Fame. Many consider him the best player not in Cooperstown.

“Richie Allen,” Willie Mays said, “was and still is, a Hall of Famer as far as I’m concerned.”

The debate over Allen’s Hall of Fame candidacy is one more aspect of a nonconformist Bill James rated as the second-most controversial player in baseball history behind Rogers Hornsby. Gossage sees little controversy when it comes to Allen. In his Hall of Fame induction speech, the Goose praised Allen as “the greatest player I ever played with.”

The Sox played ball that 1972 season with a vengeance. It was a hot time, summer in the city, and the back of the necks of baseball fans weren’t the only things dirty and gritty on Chicago’s South Side. The White Sox were getting down and dirty in the division fight with defending champion Oakland, and Windy City headlines trumpeted the daily battles:

“Sox Win, Allen Slugs Pair”

“Superman Allen Hero Again”

“Allen, Wood Lead Sox Into First Place”

Forty years later, Roland Hemond, the team’s Assistant GM and the architect of the Allen trade, remembered Allen’s transformative season as “one of the most impactful seasons a ballplayer ever had.”

Forty years later, Roland Hemond, the team’s Assistant GM and the architect of the Allen trade, remembered Allen’s transformative season as “one of the most impactful seasons a ballplayer ever had.”

As magnificent as Allen was, he was not alone in leading the White Sox. Wilbur Wood tied for the league lead in wins with 24 and led the AL in starts (49) and innings pitched (376.2). Stan Bahnsen won 21 games in his first season with the Sox; Tom Bradley won 15. Goose Gossage, a future Hall of Famer, and Terry Forster, both 20 years old, were a righty-lefty fireman tandem that combined for 13 wins. Forster fronted the bullpen with 29 saves. Carlos May contributed clutch power and a .308 batting average; Pat Kelly a team-best 32 steals.

Allen embraced his role as mentor and says the Sox did more with enthusiasm than experience. “We became tighter than pantyhose two sizes too small,” he said.

That magical summer on the South Side may have saved the Sox franchise. There had been talk during their down years that the Windy City Sox could, in fact, be gone with the wind.

Hemond’s wheeling and dealing helped bring the buzz back to the old ballpark. Home games at classic Comiskey Park saw the Sox take the field in equally classic uniforms – bright red pinstripes with the iconic “Sox” script over the chest, red numbers front and back, a White Sox patch on the sleeve, a red cap with a variation of the Sox script, red belt and red cleats.

One of the more startling renovations to Comiskey came in 1969, when AstroTurf was installed in the infield to cut field maintenance costs. Comiskey became the only park in the majors with an AstroTurf infield and an outfield of God’s green grass.

Allen, known for his dry quips, uttered what remains the most cutting criticism of artificial grass:

“If a horse won’t eat it,” he said, “I don’t want to play on it.”

The Sox’s infield may have been artificial, but their challenge to the A’s was authentic. Even with Beltin’ Bill Melton sidelined by a back injury, Chicago led the late division in late August. Wilbur Wood was a big reason why.

Despite a physical appearance that Chicago Sun-Times sports columnist Jack Griffin once compared to “the guy who just won the beer frame,” Wood was remarkably resilient. In one stretch in ’72 Wood appeared in four games in 10 days. Wood’s reliever mentality and rubber arm allowed Tanner to do something unprecedented in modern times: work with a three-man starting staff. The “Great Trio” — Wood, Bahnsen and Bradley — combined for 132 starts in ’72.

The A’s eventually won the West but the ’72 White Sox made their mark. In 2012 they were honored with induction into the Chicago Baseball Museum as the “team that saved the Sox.”

SABR member ED GRUVER has been a sportswriter for Pennsylvania dailies for 30 years and has covered the Philadelphia Phillies and Baltimore Orioles as a columnist. “October ’72” is his sixth book and second baseball book. His previous baseball book was “Koufax,” published in 2000.

Originally published: January 1, 2014. Last Updated: January 1, 2014.