Edelman: New York Mets in the Movies

Editor’s note: A version of this paper was presented at the 50th anniversary New York Mets conference at Hofstra University in April 2012.

By Rob Edelman

Of the real-life New York baseball nines that have been featured (or referenced) onscreen, the Bronx Bombers and their stars have been the most frequently represented — from Headin’ Home (1920), The Babe Comes Home (1927), and Speedy (1928), all featuring Babe Ruth, through the current Moneyball (2011). To a lesser extent, the late, lamented Brooklyn Dodgers often were depicted or referenced. In the 1940s, Dodger blue was cited in It Happened in Flatbush (1942), Whistling in Brooklyn (1943), Guadalcanal Diary (1943), and Arsenic and Old Lace (1944). In the 1950s, prior to the Bums’ abandoning the Borough of Churches, Brooklyn was represented in everything from biopics (1950’s The Jackie Robinson Story) to kiddie movies (1954’s Roogie’s Bump) to portrayals of life in a baseball tryout camp (1953’s Big Leaguer). Actually, New York Giants wannabes (as well as Edward G. Robinson’s performance as Hans Lobert and Carl Hubbell playing… Carl Hubbell) are the star attractions in Big Leaguer. And almost four decades earlier, the Jints were represented onscreen in One Touch of Nature (1917), featuring John McGraw, and Right Off the Bat (1915), starring Mike Donlin and McGraw.

Of the real-life New York baseball nines that have been featured (or referenced) onscreen, the Bronx Bombers and their stars have been the most frequently represented — from Headin’ Home (1920), The Babe Comes Home (1927), and Speedy (1928), all featuring Babe Ruth, through the current Moneyball (2011). To a lesser extent, the late, lamented Brooklyn Dodgers often were depicted or referenced. In the 1940s, Dodger blue was cited in It Happened in Flatbush (1942), Whistling in Brooklyn (1943), Guadalcanal Diary (1943), and Arsenic and Old Lace (1944). In the 1950s, prior to the Bums’ abandoning the Borough of Churches, Brooklyn was represented in everything from biopics (1950’s The Jackie Robinson Story) to kiddie movies (1954’s Roogie’s Bump) to portrayals of life in a baseball tryout camp (1953’s Big Leaguer). Actually, New York Giants wannabes (as well as Edward G. Robinson’s performance as Hans Lobert and Carl Hubbell playing… Carl Hubbell) are the star attractions in Big Leaguer. And almost four decades earlier, the Jints were represented onscreen in One Touch of Nature (1917), featuring John McGraw, and Right Off the Bat (1915), starring Mike Donlin and McGraw.

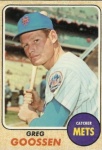

When it comes to Big Apple baseball teams and the movies, I must regretfully report that the New York Mets come in a distant fourth place. Across the decades, baseball films (as opposed to films with baseball-related sequences) spotlight the other New York nines — but never the Mets. There have been biopics of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella, but never Tom Seaver, Darryl Strawberry, or Mike Piazza. Meanwhile, quite a few New York ballplayers have appeared onscreen. Babe Ruth acted in those silent features; played himself in The Pride of the Yankees (1942), the Lou Gehrig biopic; and appeared in various short subjects. Gehrig starred in Rawhide (1938), a B-Western. Jackie Robinson played himself in The Jackie Robinson Story. And so on… But if you want to find a Met in the movies, the first name that pops into mind is Greg Goossen, the 1960s catcher-first sacker — he of the .202 batting average in his four Mets seasons. Starting in the late 1980s, Goossen worked as Gene Hackman’s stand-in and also appeared onscreen. In The Package, Loose Cannons, Class Action, Unforgiven, The Firm, Wyatt Earp, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, The Replacements, Heist, The Royal Tenenbaums, and Behind Enemy Lines, all released between 1989 and 2001, his characters respectively were: “Soldier in Provost Marshal’s Office”; “Marsh Policeman”; “Bartender at Rosatti’s”; “Fighter”; “Vietnam Veteran”; “Friend of Bullwacker”; Prison Cell Lunatic”; “Drunk #2”; “Officer #1”; “Gypsy Cab Driver”; and “CIA Spook.”

There is good news, however: When it comes to baseball on celluloid, the Mets have not been completely shut out. Far from it — and one New York Mets/Shea Stadium celluloid reference is, in my view at least, a bona-fide classic. It is found in The Odd Couple (1968), a screen adaptation of Neil Simon’s smash-hit play. One of the two central characters is, of course, New York sportswriter/slob extraordinaire Oscar Madison (Walter Matthau). Madison is forever garbed in a Mets cap, and his apartment is decorated with photos of Stan Musial, Yogi Berra, and various long-forgotten Mets of the pre-Tom Seaver era. At one point, he covers a game at Shea Stadium. The Mets are a run up on the Pittsburgh Pirates, who have loaded the bases with Bill Mazeroski coming to bat.

“That’s the ballgame,” predicts a fellow scribe (Heywood Hale Broun, in a cameo), not expecting the Mets to hold such a slim lead. “What’s the matter, you never heard of a triple play?” is Madison’s response. Just then, the writer’s new roommate and nemesis, neurotic Felix Ungar (Jack Lemmon), phones with an “emergency”: He tells Madison not to eat any frankfurters because he’s making franks and beans for dinner. At that moment, Maz smacks into a game-ending triple play. “Greatest fielding play I ever saw… [and] you missed it,” yells Broun, to Madison’s consternation. (Reportedly, Hall of Famer Roberto Clemente was scheduled to be at bat during the gag but declined the indignity.)

The sequence was filmed on location right before a Mets-Pirates game on June 27, 1967. The following day, the New York Times reported, “Scoring a dramatic ninth inning triple play, the Mets toppled the Pittsburgh Pirates for the second time in a row before 33,610 fans at Shea Stadium.” However, the next paragraph in the report began, “It was a scriptwriter’s dream,” and it was noted that the play “had been ordered by Neil Simon, the persuasive Broadway and Hollywood writer. It took two takes and four and a half minutes [and] cost approximately $10,000…” The author of the piece was not Leonard Koppett, Deane McGowen, or another Times sportswriter. It was, instead, Vincent Canby, who then was covering show business stories for the paper.

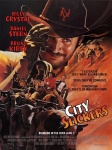

The Odd Couple is far from the lone film to feature a clever New York Mets reference. Billy Crystal, that diehard New York Yankees fan, stars in City Slickers (1991) as Mitch Robbins, a vacationing New York radio ad salesman and average American male who runs with the bulls in Pamplona garbed in — a Mets jersey and cap. On their next vacation, Mitch and his buddies head off to a western ranch where they will participate in a cattle drive. Mitch tries on different cowboy hats, which he will wear on the drive. None looks right. None feels right. But then he dons his Mets cap. Finally, he smiles. It also is amusing to see Mitch astride a horse and herding cattle while garbed in the cap. (I asked Crystal why he chose the Mets over the Yankees as the character’s favorite team while interviewing him in Cooperstown, where he was presenting to the Hall of Fame memorabilia related to 61*, his 2001 HBO movie about the Mantle-Maris 1961 home run chase. Crystal explained that he did so because the Mets organization was a big contributor to his Comic Relief charity.)

The Mets are the centerpiece of a comedy sequence in Two Weeks Notice (2002), in which Lucy Kelson (Sandra Bullock) and George Wade (Hugh Grant) have first-row seats at Shea as the New York nine takes on the San Francisco Giants. Pedro Astacio is on the mound for New York. Tsuyoshi Shinjo is at bat for the San Franciscans and the fans, as they’ve done for ages, are chanting, “Let’s Go Mets!” Shinjo smacks an Astacio pitch, but the movie audience does not see if it’s a hit or an out. The next batter (who wears #17 and has the name “DeVault” on his jersey) then hits a foul popup right where Lucy and George are seated. Mike Piazza, the Mets backstop, rushes toward the spot and crashes into Lucy, who also is trying to nab the horsehide. Piazza of course fails to make the catch and tumbles into the stands. After acknowledging George, a super-rich land developer who is as celebrated as Donald Trump, Piazza looks at Lucy with disdain and tells her, “Hey, next time go to a Yankee game.”

The Mets are the centerpiece of a comedy sequence in Two Weeks Notice (2002), in which Lucy Kelson (Sandra Bullock) and George Wade (Hugh Grant) have first-row seats at Shea as the New York nine takes on the San Francisco Giants. Pedro Astacio is on the mound for New York. Tsuyoshi Shinjo is at bat for the San Franciscans and the fans, as they’ve done for ages, are chanting, “Let’s Go Mets!” Shinjo smacks an Astacio pitch, but the movie audience does not see if it’s a hit or an out. The next batter (who wears #17 and has the name “DeVault” on his jersey) then hits a foul popup right where Lucy and George are seated. Mike Piazza, the Mets backstop, rushes toward the spot and crashes into Lucy, who also is trying to nab the horsehide. Piazza of course fails to make the catch and tumbles into the stands. After acknowledging George, a super-rich land developer who is as celebrated as Donald Trump, Piazza looks at Lucy with disdain and tells her, “Hey, next time go to a Yankee game.”

But this is not the punch line. Even though Lucy is garbed in a Mets jacket and cap, she is booed by the fans around her. Then her face is shown on the ballpark’s Diamond Vision screen and all those in attendance jeer her. They even are encouraged by Mr. Met himself — and one might surmise that she may as well move to Chicago and change her name to Steve Bartman. (Piazza also is referenced in Kate & Leopold [2001], which features a poster of the 1969 World Champions and a character who proves that he can copy any accent by impersonating a “Victorian dude who’s never seen a Mets game [and is] watching [one on] TV.”)

If Brooklynites by nature are supposed to be Mets (as opposed to Yankees) fans, then it is not surprising that Spike Lee more than occasionally references the Mets. In Do the Right Thing (1989), it is appropriate that Mookie the pizza delivery guy (who is played by Lee) shows up at work garbed in a Brooklyn Dodgers jersey. Is it because the setting is Bedford Stuyvesant, a Brooklyn neighborhood, and Mookie is a Dodgers fan? Not necessarily. What is key here is that Mookie wears a #42 Jackie Robinson jersey. (Once upon a time, Lee attempted to direct a Jackie Robinson biopic, but the project fell through.) But Lee does not ignore the Mets. For one thing, Mookie’s son wears Mets pajamas. For another, Mookie tells Vito (Richard Edson), his boss’ son, “See that game last night? Best pitcher in the game. Dwight Gooden.” Vito protests, claiming that Roger Clemens is superior. “Clemens sucks, man,” Mookie declares. “He can’t carry Dwight’s jock.”

The black-versus-Italian tension also is found in Lee’s Jungle Fever (1991). Here, Mike Tucci (Frank Vincent) and his sons (David Dundara, Michael Imperioli) watch the Mets on TV. “I’m glad they got rid of Strawberry,” one of them declares in voiceover. “He was too much fucking trouble. If he wants his ass kissed, let him go to L.A. and let Lasorda kiss it. Now he says he’s a born-again Christian. Fuck born-again. Play the fuckin’ game.” All the while, another voice is heard sarcastically chanting “Daaaaryl, Daaaaryl…” Mike and his boys wear their racism on their sleeves, and so a question arises: Is their anti-Strawberry rant meant to be racially-tinged? Would the Italians disrespect Gary Carter or Ray Knight — or John Franco or Lee Mazzilli? And regarding Do the Right Thing, would Mookie claim that Clemens was the superior hurler if he was black and Gooden was white? These are questions you’d have to pose to Spike Lee.

However, later on in Jungle Fever, Gator Purify (Samuel L. Jackson), a black crack addict, “borrows” his parents’ color TV set because, he says, he wants to “watch the Mets.” When confronted by his brother, Gator grumbles that the Mets lost yet again, referring to them as “sorry mother-fuckers.” Of course, Gator’s true intention is to sell the TV for drug money. So in the world of Spike Lee, as portrayed in Jungle Fever, no one is perfect. Whites from Brooklyn’s Bensonhurst community may be bigots. Blacks from Manhattan’s Harlem may be crackheads. One thing they do have in common is that they grouse about the Mets.

The Mets also are cited by Lee in Mo’ Better Blues (1990). The first reference is in the film’s first scene. It is 1969, and four boys with baseball gear are outside a Brooklyn brownstone imploring their pal Bleek to join them. At the insistence of his mother, Bleek declines as he is busy practicing the trumpet. His father, meanwhile, is watching the Mets on TV. The image is black-and-white. Rod Gaspar, #17, is at the plate for the New Yorkers, who are battling the Pittsburgh Pirates at Shea. Bob Moose is on the mound for the Bucs. The date is September 20, and Moose is in the process of tossing a no-hitter. Lee then cuts to the present, and Bleek (now played by Denzel Washington) has grown up to be a jazz trumpeter. Giant, his manager (played by Lee), has a gambling issue and is placing bets on games. The Mets and Pirates are meeting in a double header. “Gimme the Pirates in both games,” Giant says. “The Mets need some more black ballplayers.” Giant is no less cynical about the Yankees. “In the American League,” he adds, “gimme the Yankees over the Tigers — even though Steinbrenner needs to go.”

As in Jungle Fever, other Mets celluloid references are connected to key dates or events in the club’s history. The 1969 World Series triumph is one of the central elements in Frequency (2000). Frank Sullivan (Dennis Quaid), a New York firefighter, lives in Queens, loves his wife and son, and passionately roots for the Amazins. Frank and his boy both wear Mets caps. In one scene, parents and kids are at a picnic and a Series game is airing on a black-and-white TV. Frank snaps a photo of the group. To get them to collectively smile, he tells them: “Everybody say ‘Amazin’ Mets’.”

At the outset, we are told that Frank perished in a warehouse fire several days into the Series. Cut to 30 years later. Sullivan’s now-grown son John (Jim Caviezel) is a New York cop whose life is at its nadir. He is drinking way too much, and his wife has just left him. Of his father, he observes, “I wish I could remember him better.” But then he stumbles upon his dad’s old ham radio and, miraculously, he uses it to speak person-to-person with his father, despite the three decades that have past. In their first conversation, John observes that he will “love Ron Swoboda until the day I die.” Frequency is a film about father-son connections, of which baseball plays a central role. At the finale, we see John’s son — and Frank’s grandson — playing ball while garbed in a Mike Piazza jersey. But the core of the story involves the nabbing of a serial killer — and the manner in which the ’69 Series plays out has a key role in his downfall.

One of the momentous dates in Mets history is October 25, 1986: Game Six of the ‘86 Fall Classic, which is famous (or infamous, as the case may be) for Mookie Wilson’s groundball trickling through Bill Buckner’s legs. This date and game are the subjects of Game 6 (2004), the tale of Nicky Rogan (Michael Keaton), a Red Sox-obsessed playwright who, on the day of the game, sees a “tragedy in the making” given the Sox’ sorry history. Throughout the film, radio pundits and fans discuss the game and Nicky adds his perspective by observing, “I hate the Mets. I can’t respect them. ‘Cause when the Mets lose, they just lose… But the Red Sox… we have a rich history of really fascinating ways to lose crucial games… defeats that just keep you awake at night.”

When Dave Henderson homers in the top of the tenth inning, giving the Sox a 4-3 lead, Nicky’s companion observes that “life is good” — and Nicky adds, “Baseball is life.” But we all know what happened in the bottom of the 10th and, for Red Sox fans, baseball also is a reflection of life’s frustrations and heartbreak. When Mookie grounds to Buckner, Nicky visualizes Buckner making the play. That, of course, is an illusion. As a reality-test, the actual footage is seen — and re-seen onscreen. Even though the Mets won Game 6 — and Game 7 — Game 6 is a Boston Red Sox movie. Within the framework of the story, the Mets are the secondary players.

A fictional Mets-Dodgers playoff series plays a central role in Bad Lieutenant (1992). Over the opening credits, the distinctive voice of Chris “Mad Dog” Russo is heard on the soundtrack. Russo, hosting a talk radio sports show, sets up the scene when he declares, “Hey folks, I know the Mets are down three-zip in a best-of-seven. I don’t know a [playoff] team [that] has ever come back from three-oh down to win four straight.” (This of course is prior to the 2004 American League Championship series between the Red Sox and Yankees.) Russo continues, “I know they haven’t played well. I know the pitching’s been bad. I know no clutch hitting… ’86 and ’69 seem a long long time ago. And… goodness gracious, there’s no Donn Clendenon. But you are not out of it until you lose four games in a best-of-seven. That is all there is to it.” Then, in some back-and-forth repartee that captures the zeal of opinionated fans, Russo gets into a passionate argument with “Bruce from Bayside,” a caller who trashes the Mets and their comeback chances.

The Mets remain present in the first post-credits scene, in which the title character (Harvey Keitel), a nameless drug-abusing New York cop, drives his sons to school — and the kids continue the “debate” between “Mad Dog” and “Bruce from Bayside.” The Lieutenant’s contribution is that “Strawberry’s killing ‘em,” but it must be noted that ex-Met Darryl is now a Dodger. In Bad Lieutenant, New York is depicted as being Mets-obsessed. In several sequences set at grisly murder scenes, the Lieutenant and his fellow cops casually place bets on the series while discussing crime-related issues. Meanwhile, the Lieutenant has bet heavily on the ex-Brooklynites. “The Dodgers are a lock,” he says. But of course, they aren’t. In the next game, Strawberry stands in against the Mets David Cone and hits one of his “moonshots.” The Lieutenant’s elation dissipates upon learning that Darryl’s dinger has made the score 11-3 — Mets. And so it goes as, during this and the following three games, the Mets roar back to win them all and prevail in the series.

Meanwhile, the Lieutenant becomes increasingly desperate. After another contest, which ends on a double play ball thrown by John Franco to Kal Daniels, he grabs his gun and shoots his car radio. While all of New York is thrilled by the Mets heroics, the victories are catastrophic for the doomed Lieutenant. Throughout Bad Lieutenant, the voices of play-by-play announcers Warner Fusselle and Bob Murphy reference plenty of real-life ballplayers, from the Dodgers’ Eric Davis, Lenny Harris, Orel Hershiser, Ramon Martinez, and Mike Scioscia to the Mets’ Bobby Bonilla, Vince Coleman, Sid Fernandez, and Dwight Gooden — and it is a special treat to hear Murphy yet again describe a Mets game.

On occasion, a Mets movie reference is slight — but at least it is undeniable. In Friends With Benefits (2011), Mila Kunis and Justin Timberlake play the title characters; the “benefits” of their friendship are the sexual trysts they enjoy without the complications of an emotional attachment. In one sequence, they are going at it in bed while the Mets are on TV and there is a close-up of #7, Jose Reyes, who runs the bases after smashing a homer. Then there is a Mets logo on the screen. Several trysts later, a Mets cap is spied atop a drawer. Is the team’s presence here supposed to represent anything? I have no idea.

Shea Stadium has played a part in a number of films, most significantly perhaps in Bang the Drum Slowly (1973) if only because the story told is set in the baseball world. In the opening credits, it is noted that the “baseball sequences [were] filmed at Yankee and Shea stadiums,” and the New York Mammoths — the fictional team depicted in the story — play their home games at a very recognizable Shea Stadium. Shea also has a cameo in Kiss of Death (1995), the opening shot of which begins with a subway on elevated tracks. The camera pans an auto graveyard filled with cars in various states of disrepair. At one point, there is a name: F&F Used Auto Parts. Eventually, the camera catches a glimpse of Shea, with the presence of the ballyard helping to establish the film’s setting. During the opening credits of 3 Men and a Little Lady (1990), two of the trio and the “little lady,” who is six, are cheering the Mets at Shea. Because of her gender, the child is comically blindfolded while accompanying the guys into a Shea men’s room.

The Wiz (1978), a musical version of The Wizard of Oz, features a chase scene up and down the ballpark’s pedestrian ramps which features Dorothy (Diana Ross), her cohorts, and some motorcycle-riding meanies. Baseball references abound in Woody Allen films; in a sequence from Small Time Crooks (2000) that might be dubbed “Ray and May at Shea,” characters named Ray (played by Woody) and May (Elaine May) attend a game at Shea and look on as a Met belts a dinger. Then-Met Bernard Gilkey has a cameo in Men in Black (1997). As he roams the Shea outfield, he is distracted by a spacecraft overhead and is hit on the noggin by a fly ball. In Old Dogs (2009), “sports marketing kings” Dan (Robin Williams) and Charlie (John Travolta) have on-field access at Shea, where they take pre-game batting practice. (Thirty-one years earlier, Travolta also briefly swung a bat in Grease). They and Dan’s kids get player autographs and Mets caps, and then sit in the stands when, in a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moment, David Wright crushes the ball. Later on, Dan’s son excitedly declares that they got to “hang out with the New York Mets.”

One of the more telling Shea Stadium references is found in Alice in the Cities (1974), a West German film directed by Wim Wenders. The following analysis of the sequence, written by Scott Jordan Harris and published in 2011 in World Film Locations: New York, grabbed my attention:

We hear it before we see it. ‘Sounds like an organ,’ says our protagonist, a travelling German journalist… ‘That’s… Shea Stadium,’ he is told. We cut to the famous sports ground. A baseball game is in progress. The players, tiny and bright in their white uniforms against the grey grass are part of a team, but their smallness and their regimented distance from each other emphasizes each man’s isolation. The camera pans towards the crowd. The spectators are busy and noisy, but the dark grey spaces between them — the empty seats — suggest the loneliness that comes in crowds. The camera continues, and we see the source of the music. The organist sits, alone, in her box, creating the stadium’s atmosphere but unable to share in it. She could be at home, practising on a keyboard. The scene is over so quickly our visit to Shea seems shoehorned into the film. And this is the point. Such touristic visits to landmarks are almost always perfunctory; they give not an impression of a place, but a sense of distance from it. The scene is an exquisite expression of the isolation felt by the lead character as he travels. He compulsively snaps Polaroid pictures to record what he sees. Now, Alice in the Cities has a similar function: Shea Stadium, once one of the great landmarks in a city that sometimes seems composed only of great landmarks, was dismantled in February 2008. Here it is preserved.”

I must add here that, whenever I attend a baseball game, whether in a major league ballyard, a minor league ballyard, or a slapped-together field where youngsters are playing, I find myself exhilarated. I never feel isolated. Instead, I bond with the crowd — however large or small that crowd may be — sharing the communal experience of cheering for the favored team. It’s the same feeling I have in a movie theater, if those present are collectively connecting to what is unfolding onscreen rather than texting or discussing where they will have dinner after the show.

The final film worth citing here actually was released in 1956 — six years before the birth of the Mets. Its title is The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit. Gregory Peck stars as Tom Rath, a harried suburbanite and World War II veteran who commutes into Manhattan every workday. One day, while passing time on the train, Tom’s mind wanders and he recalls an incident from a decade earlier — and a world away from the peacetime America of the 1950s — in which he killed a young German soldier. Then, in an instant, he is thrust back into the reality of 1956 when the man sitting next to him grimly declares, “There’s no use trying. I just can’t get used to it.” “Used to what?” Tom asks. His fellow commuter responds, “The idea of the Brooklyn Dodgers as world champions.”

I would bet my Topps Tom Seaver rookie card that, if The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit had instead been made in 1970, that line would have been: “The idea of the New York Mets as world champions.” And it would have been just as credible.

ROB EDELMAN teaches film history at the University at Albany. He is the author of “Great Baseball Films,” a frequent contributor to John Thorn’s “Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game,” and he has written on baseball and baseball films for dozens of publications. His article, “Baseball Scouts in the Movies,” appears in “Can He Play: A Look at Baseball Scouts and Their Profession” (SABR, 2011), edited by Jim Sandoval and Bill Nowlin.

Related links:

- Lost and Found Baseball Films (Our Game)

- Baseball Film to 1920 (Our Game)

- Getting Hollywood to Play Ball With Moneyball (Boston Globe)

Originally published: December 12, 2012. Last Updated: December 12, 2012.