From the SABR archives: Judge Landis dismisses 1915 Federal League lawsuit

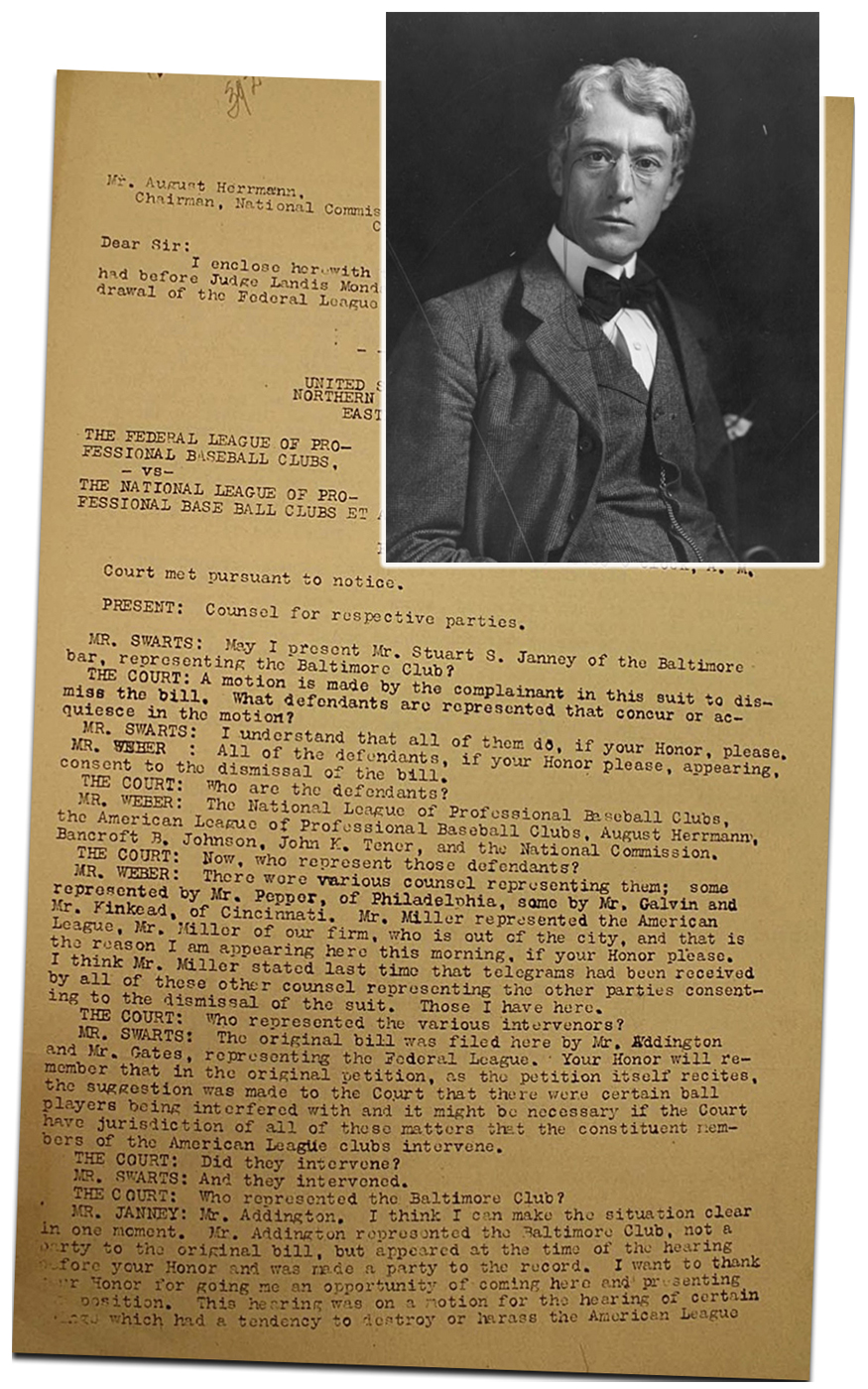

Among the many fascinating documents included in SABR’s digital archive of case files from the 1915 Federal League lawsuit against Organized Baseball is Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis’ final dismissal of the case that challenged the authority of the major leagues during the World War I era.

The Landis dismissal is published online here for the first time.

The Landis dismissal is published online here for the first time.

The Federal League case represents the first major test of how federal antitrust laws applied to the game of professional baseball. While no judgment was rendered by Landis, it provided the impetus for future federal cases that ultimately led to the famous 1922 ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court exempting major league baseball from federal antitrust laws.

The Federal League attorneys pressed the point that organized baseball was a monopoly controlling all aspects of the professional game with legally questionable practices. Organized Baseball denied such charges, emphasizing that baseball was not subject to federal antitrust law and strongly accusing the Federal League of coming into the courtroom with “unclean hands,” a result of allegedly persuading players to break existing contracts.

Judge Landis issued his closing remarks on February 7, 1916, months after the Federal League ended its second and final season. Landis acknowledged that the Federal League had a convincing argument, but he simply could not be the person responsible for altering the professional game he loved so much. Four years later, Landis was hired by the owners to be the first commissioner of baseball.

Download a copy of the original document here. Here are Judge Landis’ closing remarks, edited for clarity:

Judge Landis’ dismissal of Federal League lawsuit

February 7, 1916This motion for preliminary injunction was presented to this Court about a year ago, a little over a year ago. The whole structure of Organized Baseball was thrown into the litigation.

There were two sides to that litigation, what was known and called in the argument here and also throughout the great domain of fandom, Organized Baseball and the outlaws. …

There was a very full argument of everything involved and a very simple proposition tendered to the Court. … However, from the Court’s own knowledge of the subject matter, resulting from thirty years’ acquaintance beginning before most of you gentlemen knew anything about any such thing as baseball, convinces the Court that a temporary injunction would have been, if not destructive, vitally injurious to [Organized Baseball].

That is the plain truth of that litigation about which these two litigants were conducting this fierce controversy, and so the question which I had to decide, in addition to the legal questions submitted, was whether or not I would enter an order that would be vitally injurious if not destructive of Organized Baseball, an order in which neither litigant could leave the Court a victor.

That is the situation I had to decide. And I decided that this Court had a right to postpone the announcement of any such order.

Now, one thing more. During the preliminaries to this controversy, astute counsel on both sides gave their best endeavors to the collecting of records of the adversaries throughout the United States, the object of the lawyers on both sides being to get hold of or scrape up something that would injure the other side — I am now speaking plainly to you gentlemen about this — including an effort on both sides to get hold of something that would impugn the integrity of baseball players employed on the other side.

I want you to leave this courtroom with this statement from me, that there wasn’t the slightest evidence presented to this Court from which the most suspicious person could draw even the shadow of a notion impugning the good faith of this thing as a game or any individual ballplayer’s activity as a player.

I say that as a Judge of the Court and as an expert, I say, in dealing with this subject matter, having qualified through over thirty years of intimate observation. Call your next case.

— Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis

United States Circuit Court, Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division

The full archive of 1915 Federal League case files, which was made available online last year by SABR’s Business of Baseball Research Committee, can be viewed at SABR.org/research/1915-Federal-League-case-files. The scanned documents represent more than 2,000 pages of affidavits, contracts, exhibits, petitions, notices, complaints, and memorandums involving many of the leading baseball figures of the day, such as Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey, Pittsburgh Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss, star players like Joe Tinker and Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown, Philadelphia A’s manager Connie Mack, Brooklyn Dodgers owner Charles Ebbets, and Chicago Cubs owner Charles Weeghman.

A comprehensive new finding aid is also available for download; click here to view the PDF (116 pages). It was prepared by Tom Pardo, with generous assistance from Steve Weingarden of SABR’s Business of Baseball Committee, along with Eve Mangurten, Kyle McCafferty, Glenn Longacre, and Scott Forsyth.

All files from the Federal League court case digital archive, with certain exceptions, come from the collections of the National Archives and Records Administration, Great Lakes Region, in Chicago, Illinois. The Landis dismissal and several other documents reside in the archival collections of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York.

For a full list of SABR Research Resources available to members, visit SABR.org/research/resources.

Originally published: October 8, 2014. Last Updated: October 8, 2014.