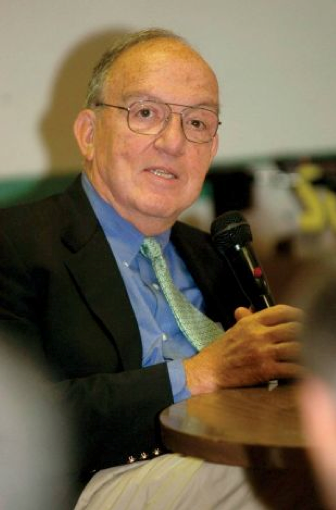

McMurray: An interview with Fay Vincent on baseball oral history

Editor’s note: This article first appeared in the SABR Oral History Committee’s Spring 2015 newsletter. To learn more about the Oral History Committee or listen to interviews, click here.

By John McMurray

When conducting oral history interviews with former major league players, which became the basis of three books that he published during the past decade, former baseball commissioner and longtime SABR member Fay Vincent would begin with the same question:

“I always started at the beginning and said to each player, ‘What got you interested in baseball?’” Vincent said. “What’s your first baseball memory? Was it your father, your mother, your uncle, your older brother, somebody down the street?’

“I always started at the beginning and said to each player, ‘What got you interested in baseball?’” Vincent said. “What’s your first baseball memory? Was it your father, your mother, your uncle, your older brother, somebody down the street?’

“I would ask that question, then the next question wouldn’t come up until ten minutes later, because that first question would generate ten minutes of really great material about how this ballplayer was introduced to baseball, sometimes by a father, sometimes by a neighbor, sometimes by a sibling. But once I did that and got them talking about their days as a child in baseball, everything really flowed.”

Long after his tenure as Commissioner of Major League Baseball had ended, Vincent continued being actively involved with baseball by conducting videotaped interviews with scores of prominent former major leaguers, which are now at the Hall of Fame. His interviews now make up three books: The Only Game in Town: Baseball Stars of the 1930s and 1940s Talk About the Game They Loved (Simon and Schuster, 2006); We Would Have Played for Nothing: Baseball Stars of the 1950s and 1960s Talk About the Game They Loved (Simon and Schuster, 2009); and It’s What’s Inside the Lines That Counts: Baseball Stars from the 1970s and 1980s Talk About the Game They Loved (Simon and Schuster, 2010).

In these books, Vincent, who served as commissioner between 1989 and 1992, paints a complete picture of each respective era by examining particular events in great detail. In spite of the complexity of topics he covered, Vincent kept his interview questions straightforward:

“I want them doing the talking, so I made the questions very simple. (When asking about the Shot Heard ‘Round the World in 1951), I would say to (Ralph) Branca or (Bobby) Thomson, ‘Look, it was absolutely a spellbinding day. Tell me about that day, where were you, how did you spend the day?’And Branca would talk about being in the bullpen. You led up to it. It flowed, at least it did for me.”

- Listen to more of Fay Vincent’s oral history interviews at the SABR Oral History Collection website

- Watch a clip of Fay Vincent’s 2004 oral history interview with former MLBPA executive director Marvin Miller

Vincent claims first to have been inspired to conduct oral history interviews by Lawrence S. Ritter, “the fellow from NYU who had done such a great job with oral history. But it was mostly players who had played in the first half of the twentieth century. Ritter did it, I think, in the ‘50s and ‘60s. I heard, those tapes, and they were fantastic. I thought, ‘nobody’s done anything since he died.’ And so, in my years after baseball, I decided that I would do it.

“The second reason was, I wanted to preserve the stories of the old Negro League players, because I realized as they were dying off, their memories and stories were irreplaceable,” said Vincent. “I was very close to Larry Doby, and, so, the first interview we did was with Doby. I knew he was sick. I knew he had cancer. I knew he wasn’t going to be around long. We went out to his house. Claire Smith, the longtime writer for the New York Times, she and I interviewed Larry for four hours, and I still think it’s a very, very important historical document. And that’s how we got started.

“I missed some of the greats,” Vincent said. “I had Stan Musial scheduled, and, at the last minute, he begged off. What happened is he began to realize he had Alzheimer’s, and he was disinclined to talk to me because of that. (Phil) Rizzuto for the same reason. As these guys recognized that they were losing some of their mental acuity, they backed away. Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams—DiMaggio agreed to do it but got sick and died. I missed Williams. My record isn’t perfect, but I did the best I could.”

Vincent does wish that the interview tapes he completed were available to a wider audience: “They’re just sitting up there at the Hall of Fame, and it is really unfortunate that there isn’t wider exposure, or a way to make Warren Spahn talking about pitching, available to kids and to people who might be interested,” said Vincent. “You think about a rainy day at the ballpark, a rain break, and why wouldn’t they run some of those tapes just to keep people interested? Whitey Ford, Yogi Berra. There are an awful lot of them. And Larry Doby’s oral history is really historic because there isn’t one of Jackie Robinson.”

In preparing to conduct an interview, Vincent confirmed that he consulted books and articles about a particular player so that he was up-to-date with basic details, but he also allowed the interview subject to provide shape and direction for the interview:

“I really let the players take the lead,” said Vincent. “I think they took me where they wanted to go. Now, we would interrupt every fifteen minutes, and I would ask them, ‘What are we missing? Is there somebody you want to talk about?’ In other words, I got the player to be a participant in the process. ‘Is there a story that we skipped over? Is there anything I’m missing here? Is there anything that you want to say about a controversial person?’ Getting Eldon Auker to talk about Leo Durocher was not easy. He hated him. But it was important to get some of that material out.”

Vincent had set up a foundation along with Herbert Allen, and their arrangement allowed Vincent to pay participating players $3,000 each to be interviewed. Many of the players, as Vincent put it, were “very happy” to be paid in return for their stories. Vincent himself did not appear during the interviews, instead asking questions of players from behind the camera. The setting for the interviews was also an important consideration: “It was a hotel room, often,” said Vincent. “Very comfortable. I think the players being interviewed have to be comfortable. Warren Spahn brought his son and friends. In other words, it was a very convivial, relaxed atmosphere.”

It is the granular aspects of particular interviews which Vincent particularly recalls. “Frank Robinson, who is a man of steel and cast-iron temperament, I got him talking about his mother, and he started crying,” said Vincent. “And I thought, ‘that alone, that one tape of Frank Robinson getting emotional over the role of his mother in his development as a ballplayer is absolutely compelling.’

“Auker was certainly a lesser-known player, but his intelligence was very high, so his memories of Ted Williams as a rookie made for some remarkable stories. I probably interviewed, I’m guessing, ten or more guys from the old Negro Leagues, who never made it to the big leagues, including Slick Surrat, who nobody ever heard of. But his story, to me, was one of the most fascinating I’d ever encountered, of growing up in a dirt poor hillside in Arkansas and eventually fighting at Guadalcanal and being an Army bulldozer operator trying to clear Henderson Field. Their stories were really moving and powerful.

“I did Pesky. I did Dominic DiMaggio. I did Tommy Henrich. I got a lot of good guys, and they were very, very interesting. Buck O’Neil, of course, was absolutely magnificent. I think if I had to pick one interview for intelligence, I would pick Warren Spahn, but if I had to pick one for, sort of, spellbinding entertainment, I would pick Buck O’Neil. And, really, above all, it was because of Buck O’Neil’s enormous enthusiasm and charm. He comes across as a black preacher, preaching the virtues of Negro League baseball.”

From a storytelling perspective, Vincent notes that baseball is distinctive. When asked why other sports do not emphasize oral history the way that baseball does, Vincent said: “Bart Giamatti had a great line. He’d say, ‘Tell me a funny basketball story.’ (Silence for effect). That really is the answer.

“There’s something about baseball,” Vincent said. “There’s a certain lighthearted appeal. Baseball is a bunch of guys sitting around a lobby waiting for the ballgame to come up and for them to go out and play. And they’re telling stories about each other. It’s just part of the tradition.”

JOHN McMURRAY is chair of SABR’s Oral History Research Committee. Contact him at sabroralhistorycommittee@gmail.com.

Originally published: May 26, 2015. Last Updated: February 2, 2025.