McMurray: Stolen bases in the Deadball Era: A relentless approach

Editor’s note: This column was originally published in the Deadball Era Research Committee’s April 2015 newsletter.

By John McMurray

In lore, the Deadball Era is often remembered for teams’ aggressive play and steadfast reliance on the stolen base. With home runs being rare, the employment of speed and daring on the bases shaped this period more than any other in baseball history. From 1901 through 1919, teams averaged more than 100 stolen bases in every season. Strikingly, from 1910 through 1914, American League teams exceeded 200 stolen bases each year on average, with National League teams trailing only slightly behind during that span. Such robust totals — there were more than 1,000 total steals in each league in seventeen of the nineteen seasons that made up the Deadball Era — would not be seen again in baseball until the early 1970s.

Yet it is also surprising how low individual stolen base totals were in each season during the Deadball Era. Though it is well known that no Deadball Era player ever stole as many as 100 bases in a season, it is less well-remembered that in six different seasons between 1901 and 1910, a mere 50 stolen bases would have been enough to lead the American League. In 1911, when the New York Giants led the National League with a still-record 347 stolen bases, the team leader was Josh Devore, with a relatively modest 61 steals.

Yet it is also surprising how low individual stolen base totals were in each season during the Deadball Era. Though it is well known that no Deadball Era player ever stole as many as 100 bases in a season, it is less well-remembered that in six different seasons between 1901 and 1910, a mere 50 stolen bases would have been enough to lead the American League. In 1911, when the New York Giants led the National League with a still-record 347 stolen bases, the team leader was Josh Devore, with a relatively modest 61 steals.

Rather than having one or two players who could steal bases effectively, as is often the case today, most Deadball Era teams could count on several legitimate base stealers. That 1911 Giants team, for one, received at least 20 steals from Devore, Fred Snodgrass, Fred Merkle, Red Murray, Larry Doyle, Buck Herzog, and Art Fletcher. Similarly, the 1909 Pittsburgh Pirates, a World Series-winning team, had six players with at least fifteen stolen bases. Teams indeed were willing to risk making outs on the basepaths. Moreover, according to Mark Halfon, author of Tales from the Deadball Era: Ty Cobb, Home Run Baker, Shoeless Joe Jackson, and the Wildest Times in Baseball History, being caught stealing did not diminish base stealers’ aggressiveness:

“Speedsters ran at will attempting to steal second base, third base or home despite a dismal success rate,” said Halfon, via e-mail. “During the Deadball Era, according to Total Baseball, ‘caught stealing’ records were kept only in 1914 and 1915 in the American League and 1915 in the National League, when runners recorded a fifty-seven percent success rate. Despite the small sample, it likely reflects the era. Actually, it is probably worse since runners prior to 1909 received credit for a theft even when a teammate got caught on the front end or back end of an attempted double steal or triple steal.”

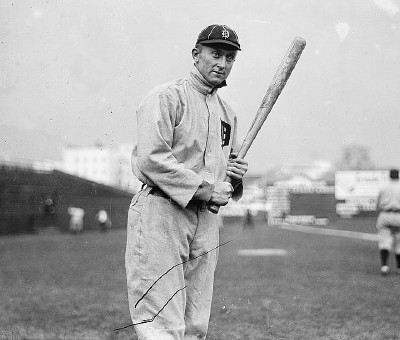

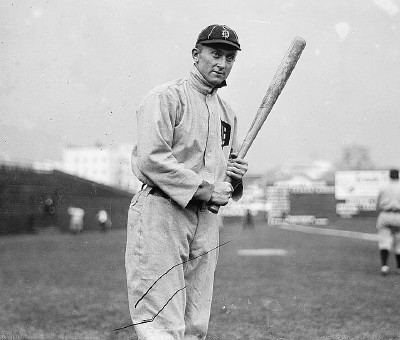

An article in The Literary Digest titled “Base-Stealing’s Sensational Decline” (April 19, 1922) points to the impact made on the bases by Ty Cobb, who led the American League in steals six times during the Deadball Era: “Ty Cobb in his prime probably caused more damage to opposing clubs’ defense by his base-stealing than he did even by his phenomenal hitting … Ty’s base stealing was the greatest individual factor in baseball offense ever seen, with the exception of Babe Ruth’s terrific slugging.”

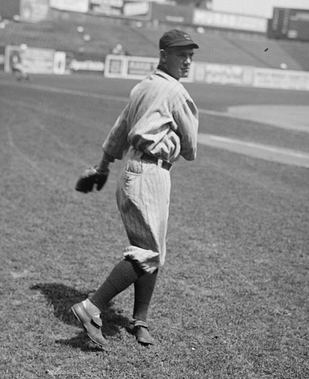

In a June 1947 article in Sportfolio, John Drebinger spoke wistfully of the Deadball Era stolen base accomplishments of Cobb and Max Carey, whom Drebinger labeled the two greatest base stealers in baseball history. “Both were fast-moving, lithe, and agile,” said Drebinger. “Cobb was swashbuckling, dynamic, and utterly ruthless in the way he crashed into opposing infielders.” Carey, in contrast, “was a runner only a little above average speed, but so perfect was his timing in getting underway, he almost made base stealing an exact science.”

Five renowned managers, whose teams routinely ranked among the game’s stolen base leaders during the Deadball Era, particularly helped to promote the period’s relentless approach on the basepaths: Frank Chance, Fred Clarke, Clark Griffith, Hughie Jennings, and John McGraw. Griffith’s teams led or tied for its respective league lead in stolen bases in eight different seasons during the Deadball Era — though, as circumstance would have it, Griffith’s team finished in first place in only one of those seasons. Of them all, manager McGraw’s dedication to stealing bases most defined the period.

Chuck Kimberly, author of Wee Willie, Old Cy and Baseball War: Scenes from the Dawn of the Deadball Era, 1900-1903 — which recently was named as a co-winner of the Larry Ritter Book Award — illustrates in comments provided by e-mail that, much like today, a team’s tendency to steal bases was likely to stem from its managerial philosophy:

Between 1901 and 1907, the Detroit Tigers had five different managers. Their stolen base totals bounced up and down in accordance with their managers’ tactical preferences. George Stallings liked aggressive baseball. His 1901 team stole 204 bases. The 1902 manager, Frank Dwyer, was an ex-pitcher who just let the boys go up to the plate and swing away. Under him, the Tigers were last in stolen bases with 130 and seventh in sacrifices with 83.

Next came Ed Barrow, whose baseball style was firmly rooted in the early 1890s, when the sacrifice was a big deal. In 1903 and 1904, when Barrow managed the first half of the season and Bobby Lowe the second half, the Tigers continued at substantially the same stolen base level (128 and 112), but sacrificed 170 and 154 times. The 170 sacrifices in 1903 led the league. In 1904 the Tigers’ sacrifice total was the third highest.

Bill Armour took over in 1905. With Cleveland from 1902 to 1904 Armour had done quite a bit of sacrificing while also being among the leaders in steals. The Tigers’ sacrifice and stolen base totals remained the pretty much the same in 1905 as they had been in 1903 and 1904. But in 1906, Armour had the team stealing a lot more often, while still remaining among the top teams in sacrifices. In 1907 Hughie Jennings became the manager and employed the aggressive style of the Old Orioles.

Then there is the question of players’ abilities. Kimberly points out that when Tom Loftus managed the Washington Senators in 1903 and 1904, an array of slow-footed players prevented Loftus’ teams from having the same level of base-stealing success that his Chicago Orphans teams did in 1900 and 1901.

Players would, of course, steal on the manager’s cue. Halfon, however, suggests that the onus was frequently on the player to decide when it was opportune to attempt a stolen base: “It varied, but I would guess that the player more often made the decision,” Halfon said. “No one told Ty Cobb when to steal, and I imagine that was the case for most of the top base stealers of the day. John McGraw preferred the steal to the bunt but nonetheless allowed his players to exercise their judgment. The Giants set the Major League record for thefts in a season in 1911 and led the National League in 1904-1906, 1911-1914 and 1916-1917, but the players decided for themselves when to run, according to Fred Snodgrass.”

“McGraw allowed initiative to his men. We stole when we thought we had the jump and when the situation demanded it … Every player on the team was expected to know how to play baseball,” Snodgrass told Lawrence Ritter for The Glory of Their Times.

“McGraw allowed initiative to his men. We stole when we thought we had the jump and when the situation demanded it … Every player on the team was expected to know how to play baseball,” Snodgrass told Lawrence Ritter for The Glory of Their Times.

Of course, stolen bases are only one element of the story, as the Deadball Era game was replete with bunts and hit-and-run plays. As Kimberly notes, a stolen base could simply have been the result of a failed hit-and-run: “In the early Deadball Era (and almost certainly throughout the era), good teams were built around fast runners. They ran a lot, but running often meant the hit-and-run play, as well as a steal attempt. Unfortunately no one kept track of the number of times the hit-and-run tactic was used. (It would have been a very difficult task). Therefore, we are left with a very blurred picture of the running game. If the batter didn’t connect with the pitch on a hit-and-run, the result could be a stolen base or, almost as likely, a runner thrown out on what looked like an attempted stolen base.”

Halfon notes that “bunting was a dominant factor throughout the Deadball Era when straight bunts, sacrifice bunts, bunts and run, bluff bunts, squeeze plays, suicide squeeze plays, and double suicide squeeze plays figured prominently.” In addition, Halfon said: “although there is no official record of total bunts per game, compelling data related to bunting is available. Virtually all of the top 100 leaders in career assists by pitchers and catchers from the modern era played in the Deadball Era; nearly every one of the top 25 modern records for career errors by pitchers and catchers played in the Deadball Era; and virtually every one of the top 50 leaders in career sacrifices played in the Deadball Era.” Halfon pointed out that Ray Chapman’s record for sacrifices in a season (67 in 1917) and Bill Rariden’s record for assists as a catcher (238 in 1915) are further evidence of how extensively bunting was used at the time.

“Stealing played a central role in the Deadball Era,” Halfon said, “but bunting figured far more prominently in the offensive strategy of the day… Undoubtedly bunting had to be a threat in virtually every inning of every game. It would be fair to estimate that each team had to be prepared to field upward of a dozen bunts per game and, consequently, bunting played a considerably more prominent role than stealing in the Deadball Era.”

Even so, stolen bases maintain a unique place in fans’ consciousness. As noted in the same 1922 article from The Literary Digest: “The stolen base is the most perfect example in baseball of the unexpected. In attack it is the farthest removed from the established rule. It injects an element of uncertainty into the game very welcome in these days of crystallized baseball methods. It allows scope for human initiative which is also very welcome.”

Aggregate stolen bases began to decline near the end of the Deadball Era. After 1917, American League teams would not collectively steal more than 1,000 bases in a season again until 1969. The National League, which had moderately higher stolen base totals during the Deadball Era, would experience a similar decline in steals after 1919. Whether it was an overt change in managerial tactics or the introduction of the livelier ball, teams in the 1920s generally stole fewer than fifty percent as many bases as they did during the Deadball Era.

Many of the well-known players from the Deadball Era gained lasting fame because of their ability to steal bases. At the same time, for every Hall of Famer such as Ty Cobb and Max Carey, there are also players like Clyde Milan and Bob Bescher, who each rose to prominence primarily because of their stolen base prowess. As teams today rely more on the stolen base, it is worthwhile to recall that such trends have roots in the game from a century ago.

JOHN McMURRAY is chair of SABR’s Deadball Era Research Committee. Contact him at deadball@sabr.org.

Originally published: April 9, 2015. Last Updated: April 9, 2015.