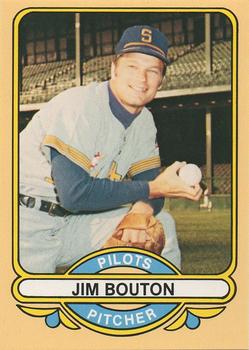

SABR Nine: Jim Bouton

Editor’s note: This article by Ryan Chamberlain was published in the March-April 2006 edition of the SABR Bulletin and is reprinted in its original form here. For more from the SABR Bulletin archives, click here.

By Ryan Chamberlain

Love him or hate him, former big-leaguer and author Jim Bouton is sure to be remembered by historians as an icon of the game. From his days as a professional baseball player, to his groundbreaking book Ball Four, Bouton has left his indelible mark.

Love him or hate him, former big-leaguer and author Jim Bouton is sure to be remembered by historians as an icon of the game. From his days as a professional baseball player, to his groundbreaking book Ball Four, Bouton has left his indelible mark.

In his most recent work, Foul Ball plus Part II, Bouton further chronicles his attempts to save Waconah Park in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, against what he sees as a culture of corruption among the city leaders of Pittsfield. The “plus Part II” edition also records his role in the discovery of a document that dates Pittsfield’s baseball origins to 1791. This document is believed to be the earliest written reference to baseball.

A SABR member since 2005, Jim Bouton will be keynote speaker at this year’s annual convention in Seattle. We’re happy to give you a preview of the fun in this edition of SABR Nine.

1. Throughout your career in the majors and the minors, who were some of your favorite players to work with?

I loved my first manager in baseball, an elderly gentleman by the name of Jimmy Gleason. This was in Kearney, Nebraska. I had just signed a baseball contract and it was my rookie season when I reported to the team. I arrived at the hotel and went up to his room and knocked on the door. And he said, “Nice to meet you, Mr. Bouton, come on in.” He said, “I’m going to give you the first rule of baseball. Don’t knock on the manager’s door without calling first.” He said, “You never know who he may be entertaining. Don’t do it again.”

I’ve always liked my managers. I’ve never really had a manager that I didn’t like. And they mostly liked me. They liked me because I loved to play ball. I was always working harder than anybody else. If we were supposed to run 20 sprints across the outfield I would run 30. I was always wanting to throw the ball. I was an annoyance to some of them because I wanted to pitch. You know, as with Joe Schultz, I was always throwing and trying to get in games. While that might have been annoying to Joe, he also understood that it was a small problem. There were enough guys who didn’t have that kind of dedication. Those were the real problems. So, I always got along well with my managers.

Coaches on the other hand … I loved Johnny Sain in particular. He was not just a great pitching coach, but a great man. Helping players not only with their pitching, but their life in general. His philosophies, his wonderful sayings: “Don’t be afraid to climb those golden stairs” or “the world doesn’t care about the labor pains, it only wants to see the baby.” You could live your life paying attention to John. There have always been some catty and annoying coaches along the way, because the coaches’ job is to curry favor with his drinking buddy, the manager. That’s usually how it works. They’re always in charge of those small things, like Frank Crosetti in charge of making sure you only take one ball out of the bag before you go out to the field. Stuff like having your hat on properly. That was with Eddie O’Brien of the Seattle Pilots. But I always thought that was more amusing than anything. Good subjects for books.

2. In your opinion, is pitching more of an art or a science?

I wouldn’t say it’s more of one than another. I’d say it’s both, it’s a combination. Science comes in the mechanics of making a ball do what you want it do. Art comes in the emotion and the mental aspects that allow you to play freely and confidently. And how you use your pitches. Using your instincts. You can do a lot of thinking and tinkering and working with your mechanics on the sidelines in between games. But once the game starts, you have to put all that aside. Now the art takes over. Instinct takes over. Now you count on your body to tell you what pitch to throw and how to throw it. Not your mind. Get rid of your mind. Like an actor in rehearsal versus an actor on stage.

3. Who is a GM that you respect the most?

It was hard to have respect for general managers in my day because the job of the general manager was to basically screw the players, and use the unfair system against them. I mean, elemental fairness said that the players should’ve been making a better share of the money, and they weren’t. The general managers were part of the unfairness. Any of them who gave it a second thought realized that, too. Most of the players in Ball Four all have stories about how they were cheated and lied to by some owner or general manager. It was almost universal. I mean Ralph Houk was a perfect example. Here he was a field manager and all for the players. The guys loved Ralph. He was a great manager. He let us alone, he let us play ball. Always had a positive attitude, “partner,” he would call us. We were all “partners.” Then he became general manager and “partner” went out the door. He wasn’t interested in us. He was interested in saving money for the owner.

4. How important has persistence been a key to your success?

It’s the most important thing. It’s so easy to say, “I’ll get to that tomorrow.” In sports, it’s so competitive by the time you get to the professional level that only the most persistent guys really get to the top. Particularly if you don’t have a tremendous amount of talent, which I didn’t have. I made myself a good pitcher. I learned how to throw a curveball when I was a kid, that helped. The fact that I was throwing overhand curves by the time I was 10 years old. You know, you learn to throw an overhand curve when you’re 10, you carry it with you for the rest of your life. It’s like learning how to play the violin when you’re six. The only way you’re going to play in a symphony orchestra or play in the big leagues is practicing that art when you’re a young child.

And I tell that to coaches. They say, “We don’t want kids to throw curveballs, they’ll get sore arms.” I say if they’re lucky they’ll have 500 sore arms, just like me. Just like any guy who finally gets in the big leagues. Hundreds of sore arms over the years. So you don’t pick up the ball for a couple of days. But if they don’t get the mechanics of it, they’re not going to learn. By the time you’re 16 it’s too late to be throwing curveballs. That’s why most of these guys come along and don’t have a curveball, they have a slider. It’s easier to teach a slider because it’s basically an off-center fastball. But the mechanics of throwing an overhand curve, which is a devastating pitch, is something you need to learn at an early age.

5. Foul Ball is your first diary since Ball Four, how was the experience similar and different?

I wrote Foul Ball for almost similar reasons. In the case of Ball Four, I really wanted to tell the story of what it’s like to play in the big leagues. I was sort of bursting with this need to tell the story. Foul Ball, here was a story I felt I had a responsibility to tell. I had uncovered something really dirty and pretty disgusting and I needed to share that. I hope over time it gets the readership it should have.

[In regards to reactions after the book was published] The exact opposite has occurred with Ball Four and Foul Ball. When Ball Four came out, there was a tremendous controversy immediately. I was castigated by players, by the team owners, by the coaches, the managers, the baseball establishment and the sportswriters. I mean I was called a Benedict Arnold and a traitor, and a Judas, a social leper. Unbelievable! But the fans read it and realized all that stuff was nonsense. Ball Four’s a funny book. It told the players’ side of the story. It isn’t that controversial anyway. They were just defending a turf that just simply didn’t need to be defended. So there was a big controversy and lots of publicity. With Foul Ball, the community that’s been affected is Pittsfield and there is a code of silence over the town. There’s absolutely no recognition that this book has been written either in hardcover or paperback. It’s a collective censorship on the city exerted by the power brokers who still run things in Pittsfield. Since Foul Ball first came out in hardcover in June of 2003 and the paperback update, which came out a few months ago, I’ve been on over 150 radio stations around the country doing interviews. Most of them phone interviews, some of them in-studio. Local stations, national stations and couple of stations broadcast to our armed forces overseas. None of those radio stations anywhere near Pittsfield, Massachusetts.

So here’s a story about the [Pittsfield] community, and a very revealing one about the problems of this community and none of the radio stations can have me on because they would lose their advertisers. They can’t have me on there. The Berkshire Eagle, a major culprit, and one of the worst newspapers in the United States, has never mentioned it. They did respond to the first book with a couple of editorials, but other than that, nothing. No reviewing of the book, no independent review, nothing. The major radio station in Hartford, the area’s only public radio station, has ignored it. I make an appearance in a bookstore in Pittsfield, and it’s not in the newspaper that I’m going to be appearing. Or it will appear the day of the event in a little calendar note or something like that, when other author appearances are played up. So they’re hoping that the book will just sort of go and fade away.

6. Do you think the socio-political problems that you faced trying to preserve the local baseball heritage of Pittsfield, including Waconah Park, are a microcosm of the issues threatening the integrity of professional baseball today?

I think what happened to us in Pittsfield is a microcosm of what’s been happening to us all over the country, cities large and small, which is that a handful of power brokers in a community will force on the public a publicly financed stadium. If people had a chance to vote on these stadiums, they would vote against them. As Mayor [Rudy] Giuliani said so clearly when responding to the question of why shouldn’t the people be able to vote on $1.6 billion for the proposed stadium for the Mets and Yankees. Mayor Giuliani said, “Because they would vote against it.” So it’s just reaching into the public till by a handful of power brokers who want to get box seats to the game, locker room access and in some cases part ownership in the team. It’s just awful and it happens in plain view, this bilking of the public.

It’s really been well-articulated in Field of Schemes by Neil deMause. It’s just a devastating look at America. You have it in New York City. Here is New York City, they’ve got schools conducting classes in stairwells, in stairwells! Books that are outdated, ceilings crumbling in schools, and here the city of New York is going to spend $300 million plus to upgrade the infrastructure around Yankee Stadium so that more than 4 million people can go to a ball game? That’s just an outrage. An absolute outrage that the custodian of a ballpark like George Steinbrenner should have the right to tear it down, even with his own money. He shouldn’t be allowed to do that. That’s like saying whoever is pastor of a church should be able to tear the church down. It’s just disgraceful. I’d like to see organizations like SABR, guys who understand the numbers, and understand the unfairness of it, throw its considerable intellectual power behind that argument. Because it does leech out into play on the field.

One of the reasons why the players make so much money is because the owners make so much money and they’re just getting their chunk of that. But the reason that these owners make so much money is because they’re able to get these publicly financed stadiums. So that’s one of the reasons why the players association has never challenged the owners anti-trust exemption, only in the area of labor relations, but not in the other areas because they benefit from the antitrust exemption. Their ability to keep out other competing leagues and to then use their monopoly power to bid one city off against another. That’s one of the reason why baseball is such a wealthy sport, because the public is indirectly financing the players salaries.

7. In the larger sense, do you think Foul Ball can be seen as a guidepost for preservationists trying to protect historic stadiums and similar public landmarks in their region?

I think so. Because it shows that it’s not enough just have a good idea or a good intention. You have to win battles, even something as obviously good for a community as a privately renovated ballpark. If that can’t get clone, than what hope is there? I think if you’re a SABR member you would learn a lot from rending Foul Ball. Anybody who’s thinking about doing something similar should read it as a primer. To get ready for what might be coming.

8. Was there anything about your playing days that you wished you could have included in Ball Four or subsequent books, but couldn’t fit it in for one reason or another?

Every once in a while a story will come to me that I remember happening and it’s not in Ball Four, but not too often. Almost all of it got in there.

9. What do you expect from the 500+ SABR members you’ll be meeting in Seattle and will you be keeping a diary?

I’m looking forward to not only being back in Seattle again, but to be in front of the SABR members. I’ve always had great affection for the organization. One of my personal friends, Jim Charlton, is in fact my oldest friend. We go back to college days in 1957, we had dormitory rooms next to each other and we’ve been friends ever since. I’m not a guy who walks around keeping a diary. There are certain things that happen in life that you have no choice but to start writing. I didn’t go into Pittsfield with the idea of writing a diary, it was only after we had run into obstacles that I realized that here was a town whose baseball destiny was in the hands of a guy in Denver, Colorado, that the mayor was corrupt, and that the bank was working against the people. It was about that time that I starting taking notes. But I was forced into taking notes by their behavior. I don’t think that will happen at the SABR convention, but I’m not making any promises.

Originally published: March 21, 2006. Last Updated: October 28, 2025.