Staples: Another hero in the family? The World War II history of Dix Ishikawa

Editor’s note: This article first appeared in the SABR Asian Baseball Research Committee’s Spring 2016 newsletter. To learn more about the Asian Baseball Committee, click here.

By Bill Staples Jr.

Throughout the course of history there have been two types of American heroes to defend the U.S. Constitution; those who pick up a gun and fight a foreign enemy, and those who take a stance against the U.S. government itself to shed light on an unjust law or practice. The grandfather of MLB slugger Travis Ishikawa (pictured at right) falls into the latter group and, even though his actions were unpopular during and after World War II, I think he too is worthy of being called a hero. Let me explain why.

Throughout the course of history there have been two types of American heroes to defend the U.S. Constitution; those who pick up a gun and fight a foreign enemy, and those who take a stance against the U.S. government itself to shed light on an unjust law or practice. The grandfather of MLB slugger Travis Ishikawa (pictured at right) falls into the latter group and, even though his actions were unpopular during and after World War II, I think he too is worthy of being called a hero. Let me explain why.

In 1849 Henry David Thoreau published Civil Disobedience, inspired by his opposition to slavery and the U.S. war in Mexico. Thoreau argued that “individuals should not permit governments to overrule or atrophy their consciences, and that they have a duty to avoid allowing such acquiescence to enable the government to make them the agents of injustice.”

Thoreau’s ideas in Civil Disobedience inspired the nonviolence movement of Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., and had a deep impact on historical figures like writer Leo Tolstoy, President John F. Kennedy, Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, and boxer Muhammad Ali. We can now add men like Yoshimitsu “Dix” Ishikawa to this list as well.

“Dix” Ishikawa (1916-2009) was just one of hundreds of Nisei men imprisoned by the U.S. government for resisting the draft during WWII. They were also pardoned by President Harry S. Truman in 1947. Ishikawa appears to be among the least vocal members of the resisters. He gave no interviews about, and left no trace of, his act of civil disobedience. In fact, his family says they know little to nothing about his personal WWII history.

Through court records obtained from Eric L. Muller, Professor of Law in Jurisprudence and Ethics at the University of North Carolina, and author of Free to Die for their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters of World War II (University of Chicago Press, 2001), we now have insight into Ishikawa’s war-time story.

- Download: Court Records – Case 10447: The United States vs. Yoshimitsu Ishikawa (PDF, 402 KB)

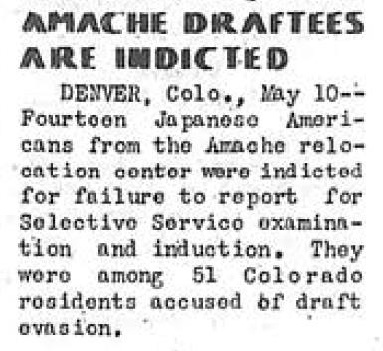

Ishikawa was born in Woodland, California, on February 13, 1916, and after President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 — roughly a week after Ishikawa’s 26th birthday — he and his family were sent to the Merced Assembly Center and then to the Amache Relocation Center in Colorado. According to the camp newspaper, The Granada Pioneer, on May 10, 1944, Ishikawa and 13 other men from Amache were indicted for failing to report for their selective service exam and induction.

They were not alone. Conscientious objectors from the other 10 relocation camps also protested the draft.

Noboru Taguma, who was relocated to the camp at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, was among the more vocal resisters to share his story after the war. When Taguma received his draft notice after being in the camps for two years, he refused to report. He said he was taking a stand for the rights of citizenship and demanded respect for his family who were unjustly incarcerated behind barbed wire. Taguma said that he would proudly serve if his parents were freed from the camps and allowed to go back to their farm in California, but until then, he refused. He would later say, “We were loyal to America, but the government itself was un-loyal to us.”

War-time is complex, and this was especially true for Japanese American males sent to incarceration camps in 1943. The majority of Nisei men did join the military, pick up a gun, and fight a foreign enemy. For others though, they felt there was a more important war to fight at home. Undoubtedly, their decision was not an easy one. While it takes a lot of courage to enter the field of battle, it also takes a lot of courage to take a non-violence stance — perhaps akin to the kind of courage that Branch Rickey demanded of Jackie Robinson when he said, “I’m looking for a ballplayer with guts enough not to fight back.”

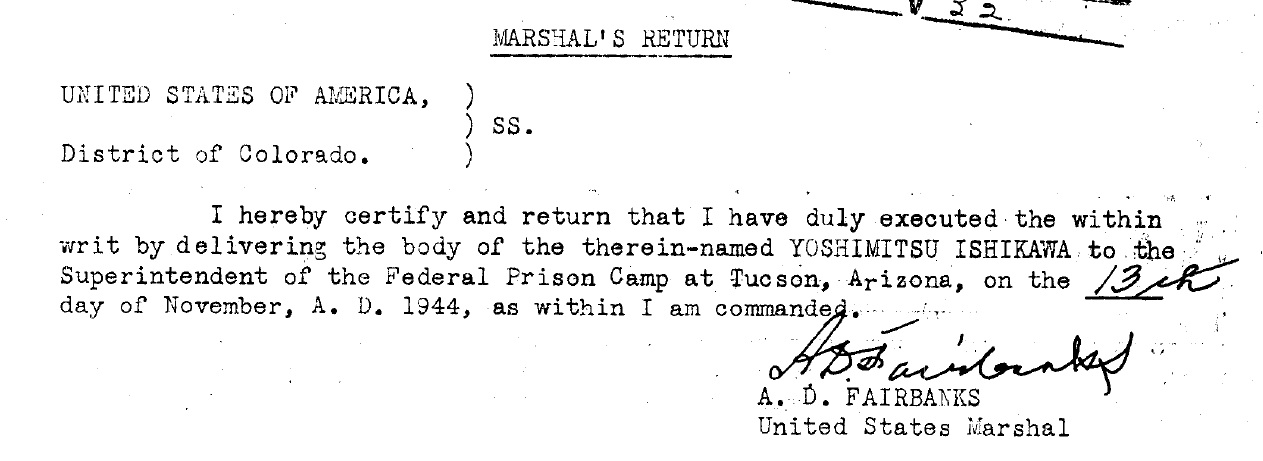

According to the court records, Ishikawa was sentenced to eight months in prison. On November 13, 1944, U.S. Marshal A.D. Fairbanks personally transported Ishikawa to the Tucson Federal Prison Camp, also known as the Catalina Federal Honor Camp.

In the prison, the group of Nisei draft resisters were used as laborers to build the roads leading up the Catalina Mountains. They also called themselves “The Tucsonians.” After the war the Tucsonians periodically held reunions and continued up to 2002. Despite receiving a pardon from President Truman, the draft resisters were still treated with hostility within the Japanese American community and beyond. In fact, it wasn’t until 2002 that the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) held a ceremony to recognize the resisters of conscience and apologize for the hostility with which the JACL treated resisters during and after the war.

For the Nisei sent to the Tucson Federal Prison Camp, there were feelings of closeness due to their unique, shared experience. Unfortunately, it appears that this was not the case for Dix Ishikawa. There is no record of him ever attending a reunion, and according to his children and grandchildren, he never spoke about his experiences during WWII.

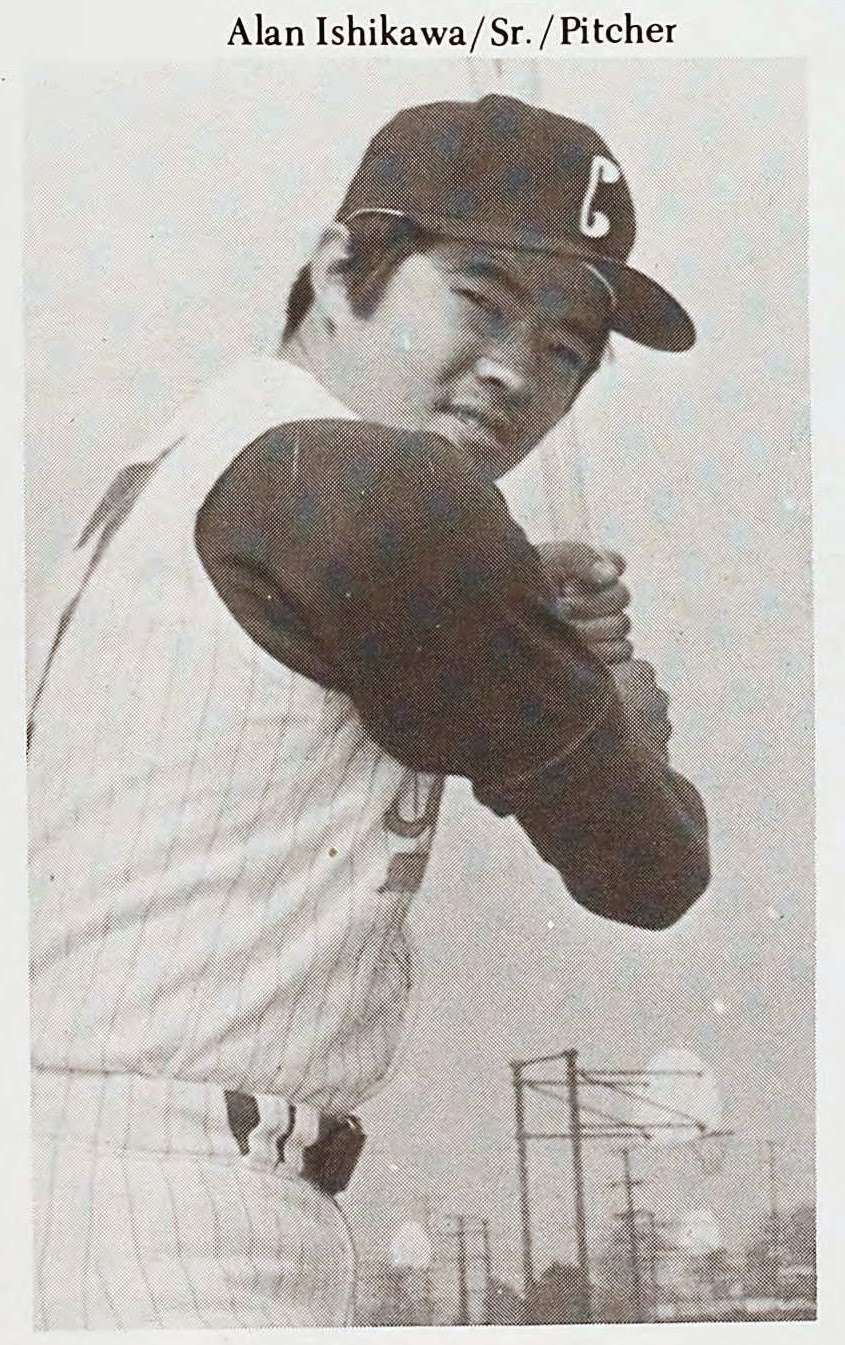

On June 5, 2009, Dix Ishikawa died at age 93. Shortly before his death, MLB slugger Travis Ishikawa talked about his grandfather’s WWII history. The article states, “Travis has never asked his grandparents about the internment camp.” Travis explained, “They never give you an opening to talk about it. … My father has never talked about it. I think it’s a cultural thing. There are some things you just don’t talk about.” Incidentally, Travis didn’t know that his father played baseball, either. His dad, Alan Ishikawa was a pitcher and outfielder for Compton High School in the early 1970s, a team that included future MLB players Dick Davis and Reggie Walton.

On June 5, 2009, Dix Ishikawa died at age 93. Shortly before his death, MLB slugger Travis Ishikawa talked about his grandfather’s WWII history. The article states, “Travis has never asked his grandparents about the internment camp.” Travis explained, “They never give you an opening to talk about it. … My father has never talked about it. I think it’s a cultural thing. There are some things you just don’t talk about.” Incidentally, Travis didn’t know that his father played baseball, either. His dad, Alan Ishikawa was a pitcher and outfielder for Compton High School in the early 1970s, a team that included future MLB players Dick Davis and Reggie Walton.

We all know that Travis Ishikawa hit a walkoff home run to clinch the pennant for the San Francisco Giants, a feat that made it possible for the team to advance to win the World Series. Little did anyone know that Travis’ life-changing home run occurred on the same date, October 16, that his grandfather registered for the Selective Service back in 1940, an act that proved to be life-changing for him too, especially after the war-time hysteria unleashed on Japanese Americans during WWII.

Ishikawa the grandson is now immortal. His name will forever be linked with other postseason heroes like Bobby Thomson, Bill Mazeroski, and Joe Carter. But Ishikawa the grandfather and his legacy as a defender of the U.S. Constitution and war-time hero was unknowingly buried with him in 2009.

Now that the court records of Yoshimitsu “Dix” Ishikawa are public, hopefully a greater appreciation for him and this little-known chapter in U.S. history will be developed.

For many years, the topic of WWII incarceration camps was a point of shame for the majority of Japanese Americans. Today, it is viewed by some as a badge of honor to have survived the camp experience. Descendants of internees also speak about the WWII camp experience with a hint of awe and pride because of the resilience displayed by their ancestors during the incarceration. I think that someday the same will be true for the relatives of the WWII Nisei draft resisters of conscience.

This transformation of attitudes can already be seen in the historic site of the Tucson Federal Prison Camp itself. It’s been renamed in honor of one of the most famous prisoners held there, Gordon Hirabayashi. It also includes an interpretive kiosk that tells the history of the prison. The kiosk not only covers Hirabayashi’s act of civil disobedience, it also honors the other wartime resisters imprisoned in Tucson. In doing so it represents a shift in our collective views about these men as defenders of civil rights and the U.S. Constitution — and as American heroes.

In his 1963 Letter from a Birmingham Jail, Martin Luther King Jr. said that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Twenty years before King wrote those words in his jail cell, Ishikawa and his fellow Nisei draft resisters knew this and believed it to be true. Because of their convictions, they took a courageous stand for justice everywhere.

BILL STAPLES JR. is the co-chair of SABR’s Asian Baseball Research Committee and the author of “Kenichi Zenimura, Japanese American Baseball Pioneer.”

- Recommended reading: To learn more about this topic, check out Prisons and Patriots: Japanese American Wartime Citizenship, Civil Disobedience, and Historical Memory, by Cherstin M. Lyon (Temple Press, 2015)

Originally published: May 4, 2016. Last Updated: May 4, 2016.