Out at Home: Baseball Draws the Color Line, 1887

This article was written by Jerry Malloy

This article was published in SABR 50 at 50

This article was originally published in SABR’s The National Pastime, No. 2 (1983).

Baseball is the very symbol, the outward and visible expression of the drive and push and rush and struggle of the raging, tearing, booming nineteenth century. — Mark Twain

. . . social inequality … means that in all the relations that exist between man and man he is to be measured and taken not according to his natural fitness and qualification, but that blind and relentless rule which accords certain pursuits and certain privileges to origin or birth. — Moses F. Walker

It was a dramatic and prophetic and prophetic performance by Jackie Robinson. The 27-year-old black second baseman opened the 1946 International League season by leading the Montreal Royals to a 14–1 victory over Jersey City. In five trips to the plate, he had four hits (including a home run) and four RBIs; he scored four runs, stole two bases, and rattled a pitcher into balking him home with a taunting danse macabre off third. Branch Rickey’s protégé had punched a hole through Organized Baseball’s color barrier with the flair and talent that would eventually take him into the Hall of Fame. The color line that Jackie Robinson shattered, though unwritten, was very real indeed. Baseball’s exclusion of the black man was so unremittingly thorough for such a long time that most of the press and public then, as now, thought that Robinson was making the first appearance of a man of his race in the history of Organized Baseball.

Actually, he represented a return of the Negro ballplayer, not merely to Organized Baseball, but to the International League as well. At least eight elderly citizens would have been aware of this. Frederick Ely, Jud Smith, James Fields, Tom Lynch, Frank Olin, “Chief” Zimmer, Pat Gillman, and George Bausewine may have noted with interest Robinson’s initiation, for all of these men had been active players on teams that opened another International League season, that of 1887. And in that year they played with or against eight black players on six different teams.

The 1887 season was not the first in which Negroes played in the International League, nor would it be the last. But until Jackie Robinson stepped up to the plate on April 18, 1946, it was the most significant. For 1887 was a watershed year for both the International League and Organized Baseball, as it marked the origin of the color line. As the season opened, the black player had plenty of reasons to hope that he would be able to ply his trade in an atmosphere of relative tolerance; by the middle of the season, however, he would watch helplessly as the IL drew up a written color ban designed to deprive him of his livelihood; and by the time the league held its offseason meetings, it became obvious that Jim Crow was closing in on a total victory.

Yet before baseball became the victim of its own prejudice, there was a period of uncertainty and fluidity, however brief, during which it seemed by no means inevitable that men would be denied access to Organized Baseball due solely to skin pigmentation. It was not an interlude of total racial harmony, but a degree of toleration obtained that would become unimaginable in just a few short years. This is the story of a handful of black baseball players who, in the span of a single season, playing in a prestigious league, witnessed the abrupt conversion of hope and optimism into defeat and despair. These men, in the most direct and personal manner, would realize that the black American baseball player soon would be ruled “out at home.”

I.

The International League (IL) is the oldest minor league in Organized Baseball. Founded in 1884 as the “Eastern” League, it would be realigned and renamed frequently during its early period. The IL was not immune to the shifting sands of financial support that plagued both minor and major leagues (not to mention individual franchises) during the nineteenth century. In 1887 the league took the risk of adding Newark and Jersey City to a circuit that was otherwise clustered in upstate New York and southern Ontario. This arrangement proved to be financially unworkable. Transportation costs alone would doom the experiment after one season. The New Jersey franchises were simply too far away from Binghamton, Buffalo, Oswego, Rochester, Syracuse, and Utica in New York, and Hamilton and Toronto in Ontario.

But, of course, no one knew this when the 1887 season opened. Fans in Newark were particularly excited, because their “Little Giants” were a new team and an instant contender. A large measure of their eager anticipation was due to the unprecedented “colored battery” signed by the team. The pitcher was George Stovey and the catcher was Moses Fleetwood Walker.

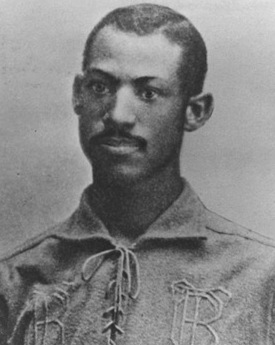

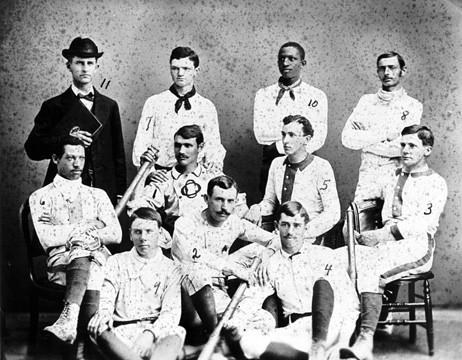

1881 Oberlin College baseball team. Fleet Walker is at left, Weldy Walker top. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

II.

“Fleet” Walker was born in Mt. Pleasant, Ohio, on the route of the Underground Railroad, on October 7, 1857. The son of a physician, he was raised in nearby Steubenville. At the age of twenty he entered the college preparatory program of Oberlin College, the first school in the United States to adopt an official admissions policy of nondiscrimination by sex, race, or creed. He was enrolled as a freshman in 1878, and attended Oberlin for the next three years. He was a good but not outstanding student in a rigorous liberal arts program. Walker also attended the University of Michigan for two years, although probably more for his athletic than his scholastic attainments. He did not obtain a degree from either institution, but his educational background was extremely sophisticated for a nineteenth century professional baseball player of whatever ethnic origin.

While at Oberlin, Walker attracted the attention of William Voltz, former sportswriter for the Cleveland Plain Dealer, who had been enlisted to form a professional baseball team to be based in Toledo. Walker was the second player signed by the team, which entered the Northwestern League in 1883. Toledo captured the league championship in its first year.

The following year Toledo was invited to join the American Association, a major league rival of the more established National League. Walker was one of the few players to be retained as Toledo made the jump to the big league. Thus did Moses Fleetwood Walker become the first black to play major-league baseball, 64 years before Jackie Robinson. Walker played in 42 games that season, batting .263 in 152 at-bats. His brother, Welday Wilberforce Walker, who was two years younger than Fleet, also played outfield in five games, filling in for injured players. Welday was 4-for-18 at the plate.

While at Toledo, Fleet Walker was the batterymate of Hank O’Day, who later became a famous umpire, and Tony Mullane, who could pitch with either hand and became the winningest pitcher, with 285 victories, outside the Hall of Fame. G. L. Mercereau, the team’s batboy, many years later recalled the sight of Walker catching barehanded, as was common in those days, with his fingers split open and bleeding. Catchers would welcome swelling in their hands to provide a cushion against the pain.

The color of Walker’s skin occasionally provoked another, more lasting, kind of pain. The Toledo Blade, on May 5, 1884, reported that Walker was “hissed . . . and insulted . . . because he was colored,” causing him to commit five errors in a game in Louisville. Late in the season the team travelled to Richmond, Virginia, where manager Charley Morton received a letter threatening bloodshed, according to Lee Allen, by “75 determined men [who] have sworn to mob Walker if he comes on the ground in a suit.” The letter, which Morton released to the press, was signed by four men who were “determined” not to sign their real names. Confrontation was avoided, for Walker had been released by the team due to his injuries before the trip to Richmond.

Such incidents, however, stand out because they were so exceptional. Robert Peterson, in Only the Ball Was White, points out that Walker was favorably received in cities such as Baltimore and Washington. As was the case throughout the catcher’s career, the press was supportive of him and consistently reported his popularity among fans. Upon his release, the Blade described him as “a conscientious player [who] was very popular with Toledo audiences,” and Sporting Life’s Toledo correspondent stated that “by his fine, gentlemanly deportment, he made hosts of friends who will regret to learn that he is no longer a member of the club.”

Walker started the 1885 season with Cleveland in the Western League, but the league folded in June. He played the remainder of 1885 and all of 1886 for the Waterbury, Connecticut, team in the Eastern League. While at Waterbury, he was referred to as “the people’s choice,” and was briefly managed by Charley Hackett, who later moved on to Newark. When Newark was accepted into the International League in 1887, Hackett signed Walker to play for him.

So in 1887 Walker was beginning his fifth season in integrated professional baseball. Tall, lean, and handsome, the 30-year-old catcher was an established veteran noted for his steady, dependable play and admired, literally, as a gentleman and a scholar. Later in the season, when the Hamilton Spectator printed a disparaging item about “the coon catcher of the Newarks,” The Sporting Nevus ran a typical response in defense of Walker: “It is a pretty small paper that will publish a paragraph of that kind about a member of a visiting club, and the man who wrote it is without doubt Walker’s inferior in education, refinement, and manliness.”

One of the reasons that Charley Hackett was so pleased to have signed Walker was that his catcher would assist in the development of one of his new pitchers, a Negro named George Washington Stovey. A 165-pound southpaw, Stovey had pitched for Jersey City in the Eastern League in 1886. Sol White, in his History of Colored Base Ball, stated that Stovey “struck out twenty-two of the Bridgeport [Connecticut] Eastern League team in 1886 and lost his game.” The Sporting News that year called Stovey “a good one, and if the team would support him they would make a far better showing. His manner of covering first from the box is wonderful.”

A dispute arose between the Jersey City and Newark clubs prior to the 1887 season concerning the rights to sign Stovey. One of the directors of the Jersey City team tried to use his leverage as the owner of Newark’s Wright Street grounds to force Newark into surrendering Stovey. But, as the Sporting Life Newark correspondent wrote, “. . . on sober second thought I presume he came to the conclusion that it was far better that the [Jersey City] club should lose Stovey than that he should lose the rent of the grounds.”

A new rule for 1887, which would exist only that one season, provided that walks were to be counted as hits. One of the criticisms of the rule was that, in an era in which one of the pitching statistics kept was the opposition’s batting average, a pitcher might be tempted to hit a batter rather than be charged with a “hit” by walking him. George Stovey, with his blazing fastball, his volatile temper, and his inability to keep either under strict control, was the type of pitcher these skeptics had in mind. He brought to the mound a wicked glare that intimidated hitters.

During the preseason contract dispute, Jersey City’s manager, Pat Powers, acknowledged Stovey’s talents, yet added:

“Personally, I do not care for Stovey. I consider him one of the greatest pitchers in the country, but in many respects I think I have more desirable men. He is head-strong and obstinate, and, consequently, hard to manage. Were I alone concerned I would probably let Newark have him, but the directors of the Jersey City Club are not so peaceably disposed.”

Newark planned to mute Stovey’s “head-strong obstinance” with the easy-going stability of Fleet Walker. That the strategy did not always work is indicated by an account in the Newark Daily Journal of a July game against Hamilton:

“That Newark won the game [14–10] is a wonder, for Stovey was very wild at times, [and] Walker had several passed balls. . . . Whether it was that he did not think he was being properly supported, or did not like the umpire’s decisions on balls and strikes, the deponent saith not, but Stovey several times displayed his temper in the box and fired the ball at the plate regardless of what was to become of everything that stood before him. Walker got tired of the business after awhile, and showed it plainly by his manner. Stovey should remember that the spectators do not like to see such exhibitions of temper, and it is hoped that he will not offend again.”

Either despite or because of his surly disposition, George Stovey had a great season in 1887. His 35 wins is a single season record that still stands in the International League. George Stovey was well on his way to establishing his reputation as the greatest Negro pitcher of the nineteenth century.

The promotional value of having the only all-Negro battery in Organized Baseball was not lost upon the press. Newspapers employed various euphemisms of the day for “Negro” to refer to Newark’s “colored,” “Cuban,” “Spanish,” “mulatto,” “African,” and even “Arabian” battery. Sporting Life wrote:

“There is not a club in the country who tries so hard to cater to all nationalities as does the Newark Club. There is the great African battery, Stovey and Walker; the Irish battery, Hughes and Derby; and the German battery, Miller and Cantz.”

The Newark correspondent for Sporting Life asked, “By the way, what do you think of our ‘storm battery,’ Stovey and Walker? Verily they are dark horses, and ought to be a drawing card. No rainchecks given when they play.” Later he wrote that “Our ‘Spanish beauties,’ Stovey and Walker, will make the biggest kind of drawing card.” Drawing card they may have been, but Stovey and Walker were signed by Newark not for promotional gimmickry, but because they were talented athletes who could help their team win.

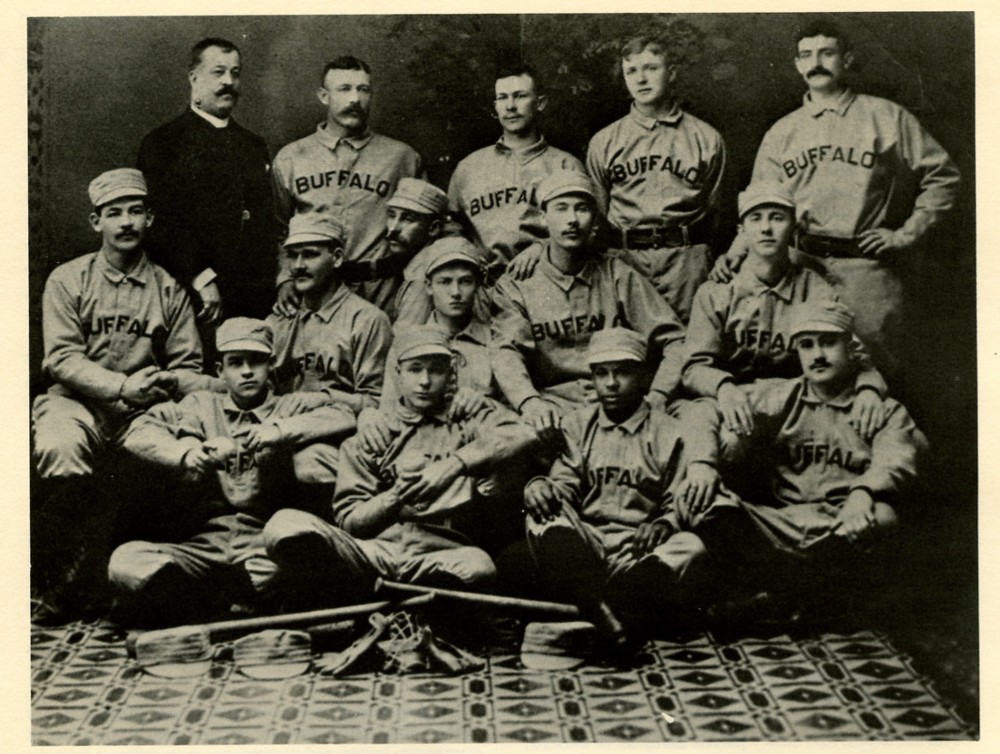

Nor were other teams reluctant to improve themselves by hiring black players. In Oswego, manager Wesley Cuny made a widely publicized, though unsuccessful, attempt to sign second baseman George Williams, captain of the Cuban Giants. Had Curry succeeded, Williams would not have been the first, nor the best, black second baseman in the league. For Buffalo had retained the services of Frank Grant, the greatest black baseball player of the nineteenth century.

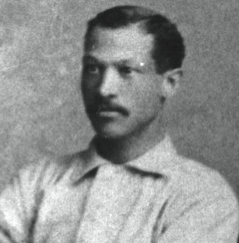

Frank Grant was beginning the second of a record three consecutive years on the same integrated baseball team. Born in 1867, he began his career in his hometown of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, then moved on to Plattsburg, New York. In 1886 he entered Organized Baseball, playing for Meriden, Connecticut, in the Eastern League until the team folded in July. Thereupon he and two white teammates signed with the Buffalo Bisons, where he led the team in hitting. By the age of 20, Grant was already known as “the Black Dunlap,” a singularly flattering sobriquet referring to Fred “Sure Shot” Dunlap, the first player to sign for $10,000 a season, and acknowledged as the greatest second baseman of his era. Sol White called Frank Grant simply “the greatest ball player of his age,” without reference to race.

In 1887, Grant would lead the International League in hitting with a .366 average. Press accounts abound with comments about his fielding skill, especially his extraordinary range. After a series of preseason exhibition games against Pittsburgh’s National League team, “Hustling Horace” Phillips, the Pittsburgh manager, complained about Buffalo’s use of Grant as a “star.” The Rochester Union quoted Phillips as saying that “This accounts for the amount of ground [Grant] is allowed to cover . . . and no attention is paid to such a thing as running all over another man’s territory.” Criticizing an infielder for his excessive range smacks of praising with faint damns. Grant’s talent and flamboyance made him popular not only in Buffalo, but also throughout the IL.

In 1890 Grant would play his last season on an integrated team for Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, of the Eastern Interstate League. His arrival was delayed by several weeks due to a court battle with another team over the rights to his services. The Harrisburg Patriot described Grant’s long-awaited appearance:

Long before it was time for the game to begin, it was whispered around the crowd that Grant would arrive on the 3:20 train and play third base. Everybody was anxious to see him come and there was a general stretch of necks toward the new bridge, all being eager to get a sight at the most famous colored ball player in the business. At 3:45 o’clock an open carriage was seen coming over the bridge with two men in it. Jim Russ’ famous trotter was drawing it at a 2:20 speed and as it approached nearer, the face of Grant was recognized as being one of the men. “There he comes,” went through the crowd like magnetism and three cheers went up. Grant was soon in the players’ dressing room and in five minutes he appeared on the diamond in a Harrisburg uniform. A great shout went up from the immense crowd to receive him, in recognition of which he politely raised his cap.

Fred Dunlap should have been proud had he ever been called “the White Grant.” Yet Grant in his later years passed into such obscurity that no one knew where or when he died (last year an obituary in the New York Age was located, revealing that Grant had died in New York on June 5, 1937).

Meanwhile, in Binghamton, Bud Fowler, who had spent the winter working in a local barbershop, was preparing for the 1887 season. At age 33, Fowler was the elder statesman of Negro ballplayers. In 1872, only one year after the founding of the first professional baseball league, Bud Fowler was [editor’s note: said to be; no proof has yet emerged] playing professionally for a white team in New Castle, Pennsylvania. Lee Allen, while historian of baseball’s Hall of Fame, discovered that Fowler, whose real name was John Jackson, was born in Cooperstown, New York, in about 1854, the son of itinerant hops-pickers. Thus, Fowler was the greatest baseball player to be born at the future site of the Hall of Fame.

As was the case with many minor league players of his time, Fowler’s career took him hopscotching across the country. In 1884 and 1885 he played for teams in Stillwater, Minnesota; Keokuk, Iowa; and Pueblo, Colorado. He played the entire 1886 season in Topeka, Kansas, in the Western League, where he hit .309. A Negro newspaper in Chicago, the Observer, proudly described Fowler as “the best second baseman in the Western League.”

Binghamton signed Fowler for 1887. The Sportsman’s Referee wrote that Fowler “. . . has two joints where an ordinary person has one. Fowler is a great ball player.” According to Sporting Life’s Binghamton correspondent:

“Fowler is a dandy in every respect. Some say that Fowler is a colored man, but we account for his dark complexion by the fact that … in chasing after balls [he] has become tanned from constant and careless exposure to the sun. This theory has the essential features of a chestnut, as it bears resemblance to Buffalo’s claim that Grant is of Spanish descent.”

Fowler’s career in the International League would be brief. The financially troubled Bings would release him in July to cut their payroll. But during this half-season, a friendly rivalry existed between Fowler and Grant. Not so friendly were some of the tactics used by opposing baserunners and pitchers. In 1889, an unidentified International League player told The Sporting News:

While I myself am prejudiced against playing in a team with a colored player, still I could not help pitying some of the poor black fellows that played in the International League. Fowler used to play second base with the lower part of his legs encased in wooden guards. He knew that about every player that came down to second base on a steal had it in for him and would, if possible, throw the spikes into him. He was a good player, but left the base every time there was a close play in order to get away from the spikes.

I have seen him muff balls intentionally, so that he would not have to try to touch runners, fearing that they might injure him. Grant was the same way. Why, the runners chased him off second base. They went down so often trying to break his legs or injure them that he gave up his infield position the latter part of last season [i.e., 1888] and played right field. This is not all.

About half the pitchers try their best to hit these colored players when [they are] at the bat. . . One of the International League pitchers pitched for Grant’s head all the time. He never put a ball over the plate but sent them in straight and true right at Grant. Do what he would he could not hit the Buffalo man, and he [Grant] trotted down to first on called balls all the time.

Fowler’s ambitions in baseball extended beyond his career as a player. As early as 1885, while in between teams, he considered playing for and managing the Orions, a Negro team in Philadelphia. Early in July 1887, just prior to his being released by Binghamton, the sporting press reported that Fowler planned to organize a team of blacks who would tour the South and Far West during the winter between 1887 and 1888. “The strongest colored team that has ever appeared in the field,” according to Sporting Life, would consist of Stovey and Walker of Newark; Grant of Buffalo; five members of the Cuban Giants; and Fowler, who would play and manage. This tour, however, never materialized.

But this was not the only capitalistic venture for Fowler in 1887. The entrepreneurial drive that would lead White to describe him as “the celebrated promoter of colored ball clubs, and the sage of base ball” led him to investigate another ill-fated venture: The National Colored Base Ball League.

In 1886 an attempt had been made to form the Southern League of Colored Base Ballists, centered in Jacksonville, Florida. Little is known about this circuit, since it was so short lived and received no national and very little local press coverage. Late in 1886, though, Walter S. Brown of Pittsburgh announced his plan of forming the National Colored Base Ball League. It, too, would have a brief existence. But unlike its Southern predecessor, Brown’s Colored League received wide publicity.

The November 18, 1886, issue of Sporting Life announced that Brown already had lined up five teams. Despite the decision of the Cuban Giants not to join the league, Brown called an organizational meeting at Eureka Hall in Pittsburgh on December 9, 1886. Delegates from Boston, Philadelphia, Washington, Baltimore, Pittsburgh, and Louisville attended. Representatives from Chicago and Cincinnati also were present as prospective investors, Cincinnati being represented by Bud Fowler.

Final details were ironed out at a meeting at the Douglass Institute in Baltimore in March 1887. The seven-team league consisted of the Keystones of Pittsburgh, Browns of Cincinnati, Capitol Citys of Washington, Resolutes of Boston, Falls City of Louisville, Lord Baltimores of Baltimore, Gorhams of New York, and Pythians of Philadelphia. (The Pythians had been the first black nine to play a white team in history, beating the City Items 27-17 on September 18,1869.) [Editor’s note: This finding since superseded.] Reach Sporting Goods agreed to provide gold medals for batting and fielding leaders in exchange for the league’s use of the Reach ball. Players’ salaries would range from $10 to $75 per month. In recognition of its questionable financial position, the league set up an “experimental” season, with a short schedule and many open dates.

“Experimental” or not, the Colored League received the protection of the National Agreement, which was the structure of Organized Baseball law that divided up markets and gave teams the exclusive right to players’ contracts. Sporting Life doubted that the league would benefit from this protection “as there is little probability of a wholesale raid upon its ranks even should it live the season out — a highly improbable contingency.” Participation in the National Agreement was more a matter of prestige than of practical benefit. Under the headline “Do They Need Protection?” Sporting Life wrote:

The progress of the Colored League will be watched with considerable interest. There have been prominent colored base ball clubs throughout the country for many years past, but this is their initiative year in launching forth on a league scale by forming a league . . . representing . . . leading cities of the country. The League will attempt to secure the protection of the National Agreement. This can only be done with the consent of all the National Agreement clubs in whose territories the colored clubs are located. This consent should be obtainable, as these clubs can in no sense be considered rivals to the white clubs nor are they likely to hurt the latter in the least financially. Still the League can get along without protection. The value of the latter to the white clubs lies in that it guarantees a club undisturbed possession of its players. There is not likely to be much of a scramble for colored players. Only two [sic] such players are now employed in professional white clubs, and the number is not likely to be ever materially increased owing to the high standard of play required and to the popular prejudice against any considerable mixture of races.

Despite the gloomy — and accurate — forecasts, the Colored League opened its season with much fanfare at Recreation Park in Pittsburgh on May 6,1887. Following “a grand street parade and a brass band concert,” about 1200 spectators watched the visiting Gorhams of New York defeat the Keystones, 11-8.

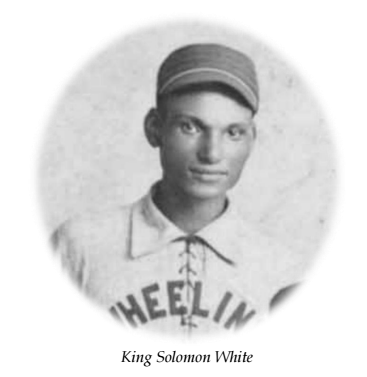

Although Walter Brown did not officially acknowledge the demise of the Colored League for three more weeks, it was obvious within a matter of days that the circuit was in deep trouble. The Resolutes of Boston traveled to Louisville to play the Falls City club on May 8. While in Louisville, the Boston franchise collapsed, stranding its players. The league quickly dwindled to three teams, then expired. Weeks later, Boston’s players were still marooned in Louisville. “At last accounts,” reported The Sporting News, “most of the Colored Leaguers were working their way home doing little turns in barbershops and waiting on table in hotels.” One of the vagabonds was Sol White, then nineteen years old, who had played for the Keystones of Pittsburgh. He made his way to Wheeling, West Virginia, where he completed the season playing for that city’s entry in the Ohio State League. (Three other blacks in that league besides White were Welday Walker, catcher N. Higgins, and another catcher, Richard Johnson.) Twenty years later he wrote:

“The [Colored] League, on the whole, was without substantial backing and consequently did not last a week. But the short time of its existence served to bring out the fact that colored ball players of ability were numerous.”

Although independent black teams would enjoy varying degrees of success throughout the years, thirty-three seasons would pass before Andrew “Rube” Foster would achieve Walter Brown’s ambitious dream of 1887: a stable all-Negro professional baseball league.

III.

The International League season was getting under way. In preseason exhibitions against major league teams, Grant’s play was frequently described as “brilliant.” Sporting Life cited the “brilliant work of Grant,” his “number of difficult one-handed catches,” and his “special fielding displays” in successive games in April. Even in an 18–4 loss to Philadelphia, “Grant, the colored second baseman, was the lion of the afternoon. His exhibition was unusually brilliant.”

Stovey got off to a shaky start, as Newark lost to Brooklyn 12-4 in the team’s exhibition opener. “Walker was clever — exceedingly clever behind the bat,” wrote the Newark Daily Journal, “yet threw wildly several times.” A few days later, though, Newark’s “colored battery” performed magnificently in a 3–2 loss at the Polo Grounds to the New York Giants, the favorite National League team of the Newark fans (hence the nickname “Little Giants.”) Stovey was “remarkably effective,” and Walker threw out the Giants’ John Montgomery Ward at second base, “something that but few catchers have been able to accomplish.” The play of Stovey and Walker impressed the New York sportswriters, as well as New York Giants captain Ward and manager Jim Mutrie who, according to White, “made an offer to buy the release of the ‘Spanish Battery,’ but [Newark] Manager Hackett informed him they were not on sale.”

Stovey and Walker were becoming very popular. The Binghamton Leader had this to say about the big southpaw:

Well, they put Stovey in the box again yesterday. You recollect Stovey, of course — the brunette fellow with the sinister fin and the demonic delivery. Well, he pitched yesterday, and, as of yore, he teased the Bingos. He has such a knack of tossing up balls that appear as large as an alderman’s opinion of himself, but you cannot hit ’em with a cellar door. There’s no use in talking, but that Stovey can do funny things with a ball. Once, we noticed, he aimed a ball right at a Bing’s commissary department, and when the Bingo spilled himself on the glebe to give that ball the right of way, it just turned a sharp corner and careened over the dish to the tune of “one strike.” What’s the use of bucking against a fellow that can throw at the flag-staff and make it curve into the water pail?

Walker, too, impressed fans and writers with his defensive skill and baserunning. In a game against Buffalo, “Walker was like a fence behind the home-plate . . . [T]here might have been a river ten feet behind him and not a ball would have gone into it.” Waxing poetic, one scribe wrote:

There is a catcher named Walker

Who behind the bat is a corker,

He throws to a base

With ease and with grace,

And steals ‘round the bags like a stalker.

Who were the other black ballplayers in the IL? Oswego, unsuccessful in signing George Williams away from the Cuban Giants, added Randolph Jackson, a second baseman from Ilion, New York, to their roster after a recommendation from Bud Fowler. (Ilion is near Cooperstown; Fowler’s real name was John Jackson — coincidence?) He played his first game on May 28. In a 5-4 loss to Newark he “played a remarkable game and hit for a double and a single, besides making the finest catch ever made on the grounds,” wrote Sporting Life. Jackson played only three more games before the Oswego franchise folded on May 31, 1887.

1887 Buffalo with Frank Grant (bottom, second from right) (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Binghamton, which already had Bud Fowler, added a black pitcher named Renfroe (whose first name is unknown). Renfroe had pitched for the Memphis team in the Southern League of Colored Base Ballists in 1886, where “he won every game he pitched but one, averaging twelve strikeouts a game for nine games. In his first game against Chattanooga he struck out the first nine men who came to bat,” wrote the Memphis Appeal; “he has great speed and a very deceptive down-shoot.” Renfroe pitched his first game for Binghamton on May 30, a 14-9 victory over Utica, before several thousand fans.

“How far will this mania for engaging colored players go?” asked Sporting Life. “At the present rate of progress the International League may ere many moons change its title to ‘Colored League.’ “During the last few days in May, seven blacks were playing in the league: Walker and Stovey for Newark, Fowler and Renfroe for Binghamton, Grant for Buffalo, Jackson for Oswego, and one player not yet mentioned: Robert Higgins. For his story, we back up and consider the state of the Syracuse Stars.

IV

The 1887 season opened with Syracuse in a state, of disarray. Off the field, ownership was reorganized after a lengthy and costly court battle in which the Stars were held liable for injuries suffered by a fan, John A. Cole, when he fell from a grandstand in 1886. Another fall that disturbed management was that of its team’s standing, from first in 1885 to a dismal sixth in 1886. Determined to infuse new talent into the club, Syracuse signed seven players from the defunct Southern League after the 1886 season. Although these players were talented, the move appeared to be backfiring when, even before the season began, reports began circulating that the Southern League men had formed a “clique” to foist their opinions on management. The directors wanted to sign as manager Charley Hackett, who, as we have seen, subsequently signed with Newark. But the clique insisted that they would play for Syracuse only if Jim Gifford, who had hired them, was named manager. The directors felt that Gifford was too lax, yet acquiesced to the players’ demand. By the end of April, the Toronto World was reporting:

“Already we hear talk of “cliqueism” in the Syracuse Club, and if there be any truth to the bushel of statement that team is certain to be doomed before the season is well under way. Their ability to play a winning game is unquestioned, but if the clique exists the club will lose when losing is the policy of the party element.”

Another offseason acquisition for the Stars was a catcher named Dick Male, from Zanesville, Ohio. Soon after he was signed in November 1886, rumors surfaced that “Male” was actually a black named Dick Johnson. Male mounted his own public relations campaign to quell these rumors. The Syracuse correspondent to Sporting Life wrote:

“Much has been said of late about Male, one of our catchers, being a colored man, whose correct name is said to be Johnson. I have seen a photo of Male, and he is not a colored man by a large majority. If he is he has sent some other fellow’s picture.”

The Sporting News’ Syracuse writer informed his readers that “Male . . . writes that the man calling him a negro is himself a black liar.”

Male’s performance proved less than satisfactory and he was released by Syracuse shortly after a 20–3 drubbing at the hands of Pittsburgh in a preseason game, in which Male played right field, caught, and allowed three passed balls. Early in May he signed with Zanesville of the Ohio State League, where he once again became a black catcher named Johnson.

As the season began, the alarming specter of selective support by the Southern League players became increasingly apparent. They would do their best for deaf-mute pitcher Ed Dundon, who was a fellow refugee, but would go through the motions when Doug Crothers or Con Murphy pitched for the Stars. Jim Gifford, the Stars’ manager, not equal to the task of controlling his team, resigned on May 17. He was replaced by “Ice Water” Joe Simmons, who had managed Walker at Waterbury in 1886.

Simmons began his regime at Syracuse by signing a 19-year-old left-handed black pitcher named Robert Higgins. Like Renfroe, Higgins was from Memphis, and it was reported that manager Sneed of Memphis “would have signed him long ago . . . but for the prejudice down there against colored men.” Besides his talents as a pitcher Higgins was so fast on the basepaths that Sporting Life claimed that he had even greater speed than Mike Slattery of Toronto, who himself was fast enough to steal 112 bases in 1887, an International League record to this day.

On May 23, two days after he signed with the Stars, Higgins pitched well in an exhibition game at Lockport, New York, winning 16-5. On May 25 the Stars made their first trip of the season to Toronto, where in the presence of 1,000 fans, Higgins pitched in his first International League game. The Toronto World accurately summed up the game with its simple headline: “DISGRACEFUL BASEBALL.” The Star team “distinguished itself by a most disgusting exhibition.” In a blatant attempt to make Higgins look bad, the Stars lost 28-8. “Marr, Bittman, and Beard . . . seemed to want the Toronto team to knock Higgins out of the box, and time and again they fielded so badly that the home team were enabled to secure many hits after the side should have been retired. In several instances these players carried out their plans in the most glaring manner. Fumbles and muffs of easy fly balls were frequent occurrences, but Higgins retained control of his temper and smiled at every move of the clique . . . Marr, Bittman, Beard and Jantzen played like schoolboys.”

Of Toronto’s 28 runs, 21 were unearned. Higgins’ catcher, Jantzen, had three passed balls, three wild throws, and three strikeouts, incurring his manager’s wrath to the degree that he was fined $50 and suspended. (On June 3 Jantzen was reinstated, only to be released on July 7.) The Sporting News reported the game prominently under the headlines: “THE SYRACUSE PLOTTERS; The Star Team Broken Up by a Multitude of Cliques; The Southern Boys Refuse to Support the Colored Pitcher.” The group of Southern League players was called the “Ku-Klux coterie” by the Syracuse correspondent, who hoped that player Harry Jacoby would dissociate himself from the group. “If it is true that he is a member of the Star Ku-Klux-Klan to kill off Higgins, the negro, he has made a mistake. His friends did not expect it. . . .”

According to the Newark Daily Journal, “Members of the Syracuse team make no secret of their boycott against Higgins. . . . They succeeded in running Male out of the club and they will do the same with Higgins.” Yet when the club returned to Syracuse, Higgins pitched his first game at Star Park on May 31, beating Oswego 11-4. Sporting Life assured its readers that “the Syracuse Stars supported [Higgins] in fine style.”

But Bob Higgins had not yet forded the troubled waters of integrated baseball. On the afternoon of Saturday, June 4, in a game featuring opposing Negro pitchers, Syracuse and Higgins defeated Binghamton and Renfroe 10-4 before 1,500 fans at Star Park. Syracuse pilot Joe Simmons instructed his players to report the next morning to P. S. Ryder’s gallery to have the team portrait taken. Two players did not comply, left fielder Henry Simon and pitcher Doug Crothers. The Syracuse correspondent for The Sporting News reported:

The manager surmised at once that there was “a nigger in the fence” and that those players had not reported because; the colored pitcher, Higgins, was to be included in the club portrait. He went over to see Crothers and found that he was right. Crothers would not sit in a group for his picture with Higgins.

After an angry exchange, Simmons informed Crothers that he would be suspended for the remainder of the season. The volatile Crothers accused Simmons of leaving debts in every city he had managed, then punched him. The manager and his pitcher were quickly separated.

There may have been an economic motive that fanned the flames of Crothers’ temper, which was explosive even under the best of circumstances: he was having a disappointing season when Simmons hired a rival and potential replacement for him. According to The Sporting News’s man in Syracuse, Crothers was not above contriving to hinder the performance of another pitcher, Dundon, by getting him liquored-up on the night before he was scheduled to pitch.

Crothers, who was from St. Louis, later explained his refusal to sit in the team portrait:

“I don’t know as people in the North can appreciate my feelings on the subject. I am a Southerner by birth, and I tell you I would have my heart cut out before I would consent to have my picture in the group. I could tell you a very sad story of injuries done my family, but it is personal history. My father would have kicked me out of the house had I allowed my picture to be taken in that group.”

Crothers’ suspension lasted only until June 18, when he apologized to his manager and was reinstated. In the meantime he had earned $25 per game pitching for “amateur” clubs. On July 2, he was released by Syracuse. Before the season ended, he played for Hamilton of the International League, and in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, all the while threatening to sue the Syracuse directors for $125.

Harry Simon, a native of Utica, New York, was not punished in any way for his failure to appear for the team portrait; of course, he did not compound his insubordination by punching his manager. The Toronto World was cynical, yet plausible, in commenting that Simon “is such a valuable player, his offense [against Higgins] seems to have been overlooked.” The sporting press emphasized that Crothers was punished for his failure to pose with Higgins more than his fisticuffs with Simmons.

Thus in a period of 10 days did Bob Higgins become the unwilling focus of attention in the national press, as the International League grappled with the question of race. Neither of these incidents — the attempt to discredit him with intentionally bad play nor the reluctance of white players to be photographed with a black teammate — was unprecedented. The day before the Stars’ appointment with the photographer, the Toronto World reported that in 1886 the Buffalo players refused to have their team photographed because of the presence of Frank Grant, which made it seem unlikely that the Bisons would have a team portrait taken in 1887 (nonetheless, they did). That Canadian paper, ever vigilant lest the presence of black ballplayers besmirch the game, also reported, ominously, that “The recent trouble among the Buffalo players originated from their dislike to [sic] Grant, the colored player. It is said that the latter’s effective use of a club alone saved him from a drubbing at the hands of other members of the team.”

Binghamton did not make a smooth, serene transition into integrated baseball. Renfroe took a tough 7-6 11-inning loss at the hands of Syracuse on June 2, eight days after Higgins’ 28-8 loss to Toronto. “The Bings did not support Renfroe yesterday,” said the Binghamton Daily Leader, “and many think the shabby work was intentional.”

On July 7, Fowler and Renfroe were released. In recognition of his considerable talent, Fowler was released only upon the condition that he would not sign with any other team in the International League. Fowler joined the Cuban Giants briefly, by August was manager of the (Negro) Gorham Club of New York, and he finished the season playing in Montpelier, Vermont.

On August 8, the Newark Daily Journal reported, “The players of the Binghamton base ball club were . . . fined $50 each by the directors because six weeks ago they refused to go on the field unless Fowler, the colored second baseman, was removed.” In view of the fact that two weeks after these fines were imposed the Binghamton franchise folded, it may be that the club’s investors were motivated less by a tender regard for social justice than by a desire to cut their financial losses.

According to the Oswego Palladium, even an International League umpire fanned the flames of prejudice:

“It is said that [Billy] Hoover, the umpire, stated in Binghamton that he would always decide against a team employing a colored player, on a close point. Why not dispense with Mr. Hoover’s services if this is true? It would be a good thing for Oswego if we had a few players like Fowler and Grant.”

There were incidents that indicated support for a color-blind policy in baseball. For example:

A citizen of Rochester has published a card in the Union and Advertiser of that city, in which he rebukes the Rochester Sunday Herald for abusing Stovey on account of his color. He says: “The young man simply discharged his duty to his club in whitewashing the Rochesters if he could. Such comments certainly do not help the home team; neither are they creditable to a paper published in a Christian community. So far as I know, Mr. Stovey has been a gentleman in his club, and should be treated with the same respect as other players.

But the accumulation of events both on and off the field drew national attention to the International League’s growing controversy over the black players. The forces lining up against the blacks were formidable and determined, and the most vociferous opposition to integrated baseball came from Toronto, where in a game with Buffalo on July 27, “The crowd confined itself to blowing their horns and shouting, ‘Kill the nigger’.” The Toronto World, under the headline “THE COLORED BALL PLAYERS DISTASTEFUL,” declared:

The World’s statement of the existence of a clique in the Syracuse team to “boy cott” Higgins, the colored pitcher, is certain to create considerable talk, if it does not amount to more, in baseball circles. A number of colored players are now in the International League, and to put it mildly their presence is distasteful to the other players. … So far none of the clubs, with the exception of Syracuse, have openly shown their dislike to play with those men, but the feeling is known to exist and may unexpectedly come to the front. The chief reason given for McGlone’s* refusal to sign with Buffalo this season is that he objected to playing with Grant.

[* John McGlone’s scruples in this regard apparently were malleable enough to respond to changes in his career fortunes. In September 1888 he signed with Syracuse, thereby acquiring two black teammates — Fleet Walker and Bob Higgins.]

A few weeks later the World averred, in a statement reprinted in Sporting Life:

There is a feeling, and a rather strong one too, that an effort be made to exclude colored players from the International League. Their presence on the teams has not been productive of satisfactory results, and good players as some of them have shown themselves, it would seem advisable to take action of some kind, looking either to their non-engagement or compelling the other element to play with them.

Action was about to be taken.

July 14, 1887 would be a day Tommy Daly would never forget. Three thousand fans went to Newark’s Wright Street grounds to watch an exhibition game between the Little Giants and the most glamorous team in baseball: Adrian D. (Cap) Anson’s Chicago White Stockings. Daly, who was from Newark, was in his first season with the White Stockings, forerunners of today’s Cubs. Before the game he was presented with gifts from his admirers in Newark. George Stovey would remember the day, too. And for Moses Fleetwood Walker, there may have been a sense of déjà vu — for Walker had crossed paths with Anson before.

Anson, who was the first white child born among the Pottawattomie Indians in Marshalltown, Iowa, played for Rockford and the Philadelphia Athletics in all five years of the National Association and 22 seasons for Chicago in the National League, hitting over .300 in all but two. He also managed the Sox for 19 years. From 1880 through 1888, Anson’s White Stockings finished first five times, and second once. Outspoken, gruff, truculent, and haughty, Anson gained the respect, if not the esteem, of his players, as well as opponents and fans throughout the nation. Cigars and candy were named after him, and little boys would treasure their Anson-model baseball bats as their most prized possessions. He was a brilliant tactician with a flair for the dramatic. In 1888, for example, he commemorated the opening of the Republican national convention in Chicago by suiting up his players in black, swallow-tailed coats.

In addition to becoming the first player to get 3,000 hits, Anson was the first to write his autobiography. A Ball Player’s Career, published in 1900, does not explicitly delineate Anson’s views on race relations. It does, however, devote several pages to his stormy relationship with the White Stockings’ mascot, Clarence Duval, who despite Anson’s vehement objections was allowed to take part in the round-the-world tour following the 1888 season. Anson referred to Duval as “a little darkey,” a “coon,” and a “no account nigger.”

In 1884, when Walker was playing for Toledo, Anson brought his White Stockings into town for an exhibition. Anson threatened to pull his team off the field unless Walker was removed. But Toledo’s manager, Charley Morton, refused to comply with Anson’s demand, and Walker was allowed to play. Years later Sporting Life would write:

“The joke of the affair was that up to the time Anson made his “bluff” the Toledo people had no intention of catching Walker, who was laid up with a sore hand, but when Anson said he wouldn’t play with Walker, the Toledo people made up their minds that Walker would catch or there wouldn’t be any game.”

But by 1887 times had changed, and there was no backing Anson down. The Newark press had publicized that Anson’s White Stockings would face Newark’s black Stovey. But on the day of the game it was Hughes and Cantz who formed the Little Giants’ battery. “Three thousand souls were made glad,” glowed the Daily Journal after Newark’s surprise 9-4 victory, “while nine were made sad.” The Evening News attributed Stovey’s absence to illness, but the Toronto World got it right in reporting that “Hackett intended putting Stovey in the box against the Chicagos, but Anson objected to his playing on account of his color.”

On the same day that Anson succeeded in removing the “colored battery,” the directors of the International League met in Buffalo to transfer the ailing Utica franchise to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. It must have pleased Anson to read in the next day’s Newark Daily Journal:

THE COLOR LINE DRAWN IN BASEBALL. The International League directors held a secret meeting at the Genesee House yesterday, and the question of colored players was freely discussed. Several representatives declared that many of the best players in the league are anxious to leave on account of the colored element, and the board finally directed Secretary White to approve of no more contracts with colored men.

Whether or not there was a direct connection between Anson’s opposition to playing against Stovey and Walker and, on the same day, the International League’s decision to draw the color line is lost in history. For example, was the league responding to threats by Anson not to play lucrative exhibitions with teams of any league that permitted Negro players? Interestingly, of the six teams which voted to install a color barrier — Binghamton, Hamilton, Jersey City, Rochester, Toronto, and Utica — none had a black player; the four teams voting against it — Buffalo, Oswego, Newark, and Syracuse — each had at least one.

In 1907, Sol White excoriated Anson for possessing “all the venom of a hate which would be worthy of a Tillman or a Vardaman of the present day…” [Sen. Benjamin R. (“Pitchfork Ben”) Tillman, of South Carolina, and Gov. James K. Vardaman, of Mississippi, were two of the most prominent white supremacists of their time.]

Just why Adrian C. Anson . . . was so strongly opposed to colored players on white teams cannot be explained. His repugnant feeling, shown at every opportunity, toward colored ball players, was a source of comment throughout every league in the country, and his opposition, with his great popularity and power in baseball circles, hastened the exclusion of the black man from the white leagues.

Subsequent historians have followed Sol White’s lead and portrayed Anson as the meistersinger of a chorus of racism who, virtually unaided, disqualified an entire race from baseball. Scapegoats are convenient, but Robert Peterson undoubtedly is correct:

“Whatever its origin, Anson’s animus toward Negroes was strong and obvious. But that he had the power and popularity to force Negroes out of organized baseball almost single-handedly, as White suggests, is to credit him with more influence than he had, or for that matter, than he needed.”

The International League’s written color line was not the first one drawn. In 1867 the National Association of Base Ball Players, the loosely organized body which regulated amateur baseball, prohibited its members from accepting blacks. The officers candidly explained their reason:

“If colored clubs were admitted there would be in all probability some division of feeling, whereas, by excluding them no injury could result to anybody and the possibility of any rupture being created on political grounds would be avoided.”

This 1867 ban shows that even if blacks were not playing baseball then, there were ample indications that they would be soon. But the NABBP would soon disappear, as baseball’s rapidly growing popularity fostered professionalism. Also, its measure was preventative rather than corrective: it was not intended to disqualify players who previously had been sanctioned. And, since it applied only to amateurs, it was not intended to deprive anyone of his livelihood.

Press response to the International League’s color line generally was sympathetic to the Negroes — especially in cities with teams who had employed black players. The Newark Call wrote:

If anywhere in this world the social barriers are broken down it is on the ball field. There many men of low birth and poor breeding are the idols of the rich and cultured; the best man is he who plays best. Even men of churlish dispositions and coarse hues are tolerated on the field. In view of these facts the objection to colored men is ridiculous. If social distinctions are to be made, half the players in the country will be shut out. Better make character and personal habits the test. Weed out the toughs and intemperate men first, and then it may be in order to draw the color line.

The Rochester Post-Express printed a shrewd and sympathetic analysis by an unidentified “old ball player, who happens to be an Irishman and a Democrat”:

We will have to stop proceedings of that kind. The fellows who want to proscribe the Negro only want a little encouragement in order to establish class distinctions between people of the white race. The blacks have so much prejudice to overcome that I sympathize with them and believe in frowning down every attempt by a public body to increase the burdens the colored people now carry. It is not possible to combat by law the prejudice against colored men, but it is possible to cultivate a healthy public opinion that will effectively prevent any such manifestation of provincialism as that of the ball association. If a negro can play better ball than a white man, I say let him have credit for his ability. Genuine Democrats must stamp on the color line in order to be consistent.

“We think,” wrote the Binghamton Daily Leader, “the International League made a monkey of itself when it undertook to draw the color line”; and later the editor wondered “if the International League proposes to exclude colored people from attendance at the games.” Welday Walker used a similar line of reasoning in March 1888. Having read an incorrect report that the Tri-State League, formerly the Ohio State League, of which Welday Walker was a member, had prohibited the signing of Negroes, he wrote a letter to league president W. H. McDermitt. Denouncing any color line as “a disgrace to the present age,” he argued that if Negroes were to be barred as players, then they should also be denied access to the stands.

The sporting press stated its admiration for the talents of the black players who would be excluded. “Grant, Stovey, Walker, and Higgins,” wrote Sporting Life, “all are good players and behave like gentlemen, and it is a pity that the line should have been drawn against them.” That paper’s Syracuse correspondent wrote “Dod gast the measly rules that deprives a club of as good a man as Bob Higgins. . . .” Said the Newark Daily Journal, “It is safe to say that Moses F. Walker is mentally and morally the equal of any director who voted for the resolution.”

Color line or no color line, the season wore on. Buffalo and Newark remained in contention until late in the season. Newark fell victim to injuries, including one to Fleet Walker. Grant’s play deteriorated, although he finished the year leading the league in hitting. Toronto, which overcame internal strife of its own, came from the back of the pack, winning 22 of its last 26 games; they may have been aided by manager Charley Cushman’s innovative device of having his infielders wear gloves on their left hands. On September 17, Toronto swept a doubleheader from Newark at home before 8,000 fans to take first place. One week later they clinched their first International League title. To commemorate the triumphant season, the Canadian Pacific Railway shipped a 160-foot tall pine, “the second tallest in America,” across the continent. Atop this pole would fly the 1887 International League pennant.

Before the season ended there was one further flareup of racial prejudice that received national, attention. On Sunday, September 11, Chris Von der Ahe, owner of the St. Louis Browns, canceled an exhibition game that was scheduled for that day in West Farms, New York, against the Cuban Giants. Led by its colorful and eccentric owner, and its multitalented manager-first baseman, Charles Comiskey, the Browns were the Chicago White Stockings of the American Association. At ten o’clock in the morning Von der Ahe notified a crowd of 7,000 disappointed fans that his team was too crippled by injuries to compete. The real reason, though, was a letter Von der Ahe had received the night before, signed by all but two of his players (Comiskey was one of the two):

Dear Sir: We, the undersigned members of the St. Louis Base Ball Club, do not agree to play against negroes tomorrow. We will cheerfully play against white people at any time, and think by refusing to play, we are only doing what is right, taking everything into consideration and the shape the team is in at present.

The Cuban Giants played, instead, a team from Danbury, New York, as Cuban Giant manager Jim Bright angrily threatened to sue the Browns. Von der Ahe tried to mollify Bright with a promise to reschedule the exhibition, a promise that would be unfulfilled. The Browns’ owner singled out his star third baseman, Arlie Latham, for a $100 fine. Von der Ahe did not object to his players’ racial prejudice. In fact, he was critical of them not for their clearly stated motive for refusing to play, but for their perceived lack of sincerity in pursuing their objective:

“The failure to play the game with the Cuban Giants cost me $1000. If it was a question of principle with any of my players, I would not say a word, but it isn’t. Two or three of them had made arrangements to spend Sunday in Philadelphia, and this scheme was devised so that they would not be disappointed.”

VI.

There was considerable speculation throughout the offseason that the International League would rescind its color line, or at least modify it to allow each club one Negro. At a meeting at the Rossin House in Toronto on November 16,1887, the league dissolved itself and reorganized under the title International Association (IA). Buffalo and Syracuse, anxious to retain Grant and Higgins, led the fight to eliminate the color line. Syracuse was particularly forceful in its leadership. The Stars’ representatives at the Toronto meeting “received a letter of thanks from the colored citizens of [Syracuse] for their efforts in behalf of the colored players,” reported Sporting Life. A week earlier, under the headline “Rough on the Colored Players,” it had declared:

“At the meeting of the new International Association, the matter of rescinding the rule forbidding the employment of colored players was forgotten. This is unfortunate, as the Syracuse delegation had Buffalo, London, and Hamilton, making four in favor and two [i.e., Rochester and Toronto] against it.”

While the subject of the color line was not included in the minutes of the proceedings, the issue apparently was not quite “forgotten.” An informal agreement among the owners provided a cautious retreat. By the end of the month, Grant was signed by Buffalo, and Higgins was retained by Syracuse for 1888. Fleet Walker, who was working in a Newark factory crating sewing machines for the export trade, remained uncommitted on an offer by Worcester, as he waited “until he finds whether colored players are wanted in the International League [sic]. He is very much a gentleman and is unwilling to force himself in where he is not wanted.” His doubts assuaged, he signed, by the end of November, with Syracuse, where, in 1888 he would once again join a black pitcher. The Syracuse directors had fired manager Joe Simmons, and replaced him with Charley Hackett. Thus, Walker would be playing for his third team with Hackett as manager. He looked forward to the next season, exercising his throwing arm by tossing a claw hammer in the air and catching it. After a meeting in Buffalo in January 1888, Sporting Life summarized the IA’s ambivalent position on the question of black players:

“At the recent International Association meeting there was some informal talk regarding the right of clubs to sign colored players, and the general understanding seemed to be that no city should be allowed more than one colored man. Syracuse has signed two whom she will undoubtedly be allowed to keep. Buffalo has signed Grant, but outside of these men there will probably be no colored men in the league.”

Frank Grant would have a typical season in Buffalo in 1888, where he was moved to the outfield to avoid spike wounds. For the third straight year his batting average (.346) was the highest on the team. Bob Higgins, the agent and victim of too much history, would, according to Sporting Life, “give up his $200 a month, and return to his barbershop in Memphis, Tennessee,” despite compiling a 20–7 record.

Fleet Walker, catching 76 games and stealing 30 bases, became a member of a second championship team, the first since Toledo in 1883. But his season was blighted by a third distasteful encounter with Anson. In an exhibition game at Syracuse on September 27, 1888, Walker was not permitted to play against the White Stockings. Anson’s policy of refusing to allow blacks on the same field with him had become so well-known and accepted that the incident was not even reported in the white press. The Indianapolis World noted the incident, which by now apparently was of interest only to black readers:

“Fowler, Grant, and Stovey played many more seasons, some with integrated teams, some on all-Negro teams in white leagues in organized baseball, some on independent Negro teams. Fowler and Grant stayed one step ahead of the color line as it proceeded westward.”

Fleet Walker continued to play for Syracuse in 1889, where he would be the last black in the International League until Jackie Robinson. Walker’s career as a professional ballplayer ended in the relative obscurity of Terre Haute, Indiana (1890) and Oconto, Wisconsin (1891).

In the spring of 1891 Walker was accused of murdering a convicted burglar by the name of Patrick Murphy outside a bar in Syracuse. When he was found not guilty “immediately a shout of approval, accompanied by clapping of hands and stamping of feet, rose from the spectators,” according to Sporting Life. His baseball career over, he returned to Ohio and embarked on various careers. He owned or operated the Cadiz, Ohio, opera house, and several motion picture houses, during which time he claimed several inventions in the motion picture industry. He was also the editor of a newspaper, The Equator, with the assistance of his brother Welday.

In 1908 he published a 47-page booklet entitled Our Home Colony; A Treatise on the Past, Present and Future of the Negro Race in America. According to the former catcher, “The only practical and permanent solution of the present and future race troubles in the United States is entire separation by emigration of the Negro from America.” Following the example of Liberia, “the Negro race can find superior advantages, and better opportunities . . . among people of their own race, for developing the innate powers of mind and body. . . .” The achievement of racial equality “is contrary to everything in the nature of man, and [it is] almost criminal to attempt to harmonize these two diverse peoples while living under the same government.” The past 40 years, he wrote, have shown “that instead of improving we are experiencing the development of a real caste spirit in the United States.”

Fleet Walker died of pneumonia in Cleveland at age 66 on May 11, 1924, and was buried in Union Cemetery in Steubenville, Ohio. His brother Welday died in Steubenville 13 years later at the age of 77.

VII.

In The Strange Career of Jim Crow, historian C. Vann Woodward identifies the late 1880s as a “twilight zone that lies between living memory and written history,” when “for a time old and new rubbed shoulders — and so did black and white — in a manner that differed significantly from Jim Crow of the future or slavery of the past.” He continued:

“… a great deal of variety and inconsistency prevailed in race relations from state to state and within a state. It was a time of experiment, testing, and uncertainty — quite different from the time of repression and rigid uniformity that was to come toward the end of the century. Alternatives were still open and real choices had to be made.”

Sol White and his contemporaries lived through such a transition period, and he identified the turning point at 1887. Twenty years later he noted the deterioration of the black ballplayer’s situation. Although White could hope that one day the black would be able to “walk hand-in-hand with the opposite race in the greatest of all American games — base ball,” he was not optimistic:

“As it is, the field for the colored professional is limited to a very narrow scope in the base ball world. When he looks into the future he sees no place for him. . . . Consequently he loses interest. He knows that, so far shall I go, and no farther, and, as it is with the profession, so it is with his ability.”

The “strange careers” of Moses Walker, George Stovey, Frank Grant, Bud Fowler, Robert Higgins, Sol White, et al., provide a microcosmic view of the development of race relations in the society at large, as outlined by Woodward. The events of 1887 offer further evidence of the old saw that sport does not develop character — it reveals it.

JERRY MALLOY (1946-2000) was a pioneer researcher who has been honored by the creation of an annual Negro League Conference named for him, as well as a book prize. His first great contribution to baseball history was “Out at Home: Baseball Draws the Color Line, 1887.” This monumentally important essay, published in The National Pastime in 1983, transformed our understanding of Black baseball and won commendation from C. Vann Woodward, the preeminent historian of American race relations. Malloy’s subsequent work included a contextual republication of Sol White’s “History of Colored Baseball with Other Documents on the Early Black Game, 1886–1936.”