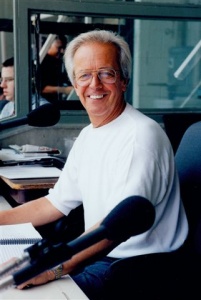

Marty Brennaman

On July 23, 2000, Marty Brennaman, radio voice of the Cincinnati Reds since 1974, was honored by the Baseball Hall of Fame with the Ford C. Frick Award, the highest award bestowed on a baseball broadcaster. (Honored with Hall of Fame induction that day were former Reds manager Sparky Anderson and former Reds first baseman Tony Perez.)

On July 23, 2000, Marty Brennaman, radio voice of the Cincinnati Reds since 1974, was honored by the Baseball Hall of Fame with the Ford C. Frick Award, the highest award bestowed on a baseball broadcaster. (Honored with Hall of Fame induction that day were former Reds manager Sparky Anderson and former Reds first baseman Tony Perez.)

No stranger to controversy, Brennaman had already indicated that in his acceptance speech he would make a statement in support of Pete Rose’s reinstatement to baseball. Bob Feller and Ralph Kiner had announced that if Brennaman made such comments in support of Rose, they and other Hall of Famers were prepared to walk out on his speech. As the assembled crowd listened anxiously, Brennaman thanked several of the players from the 1975 and 1976 World Champion Reds teams and then paid tribute to those “who should be here,” ending the list “and yes, by God, Peter Edward Rose.”1 None of the Hall of Famers left the stage. When he returned to his seat after his speech, Brennaman recalled that Feller turned to him and said, “I don’t agree with you but I respect the fact that you said what you had to say.”2 The incident was emblematic of a key facet of Brennaman’s career, which continued through the first two decades of the 21st century until his retirement at the end of the 2019 season: He has been known not only for his accurate and entertaining play-by-play, but also for being unafraid to express his opinions.

The longtime Reds broadcaster was born Franchester Martin Brennaman, Jr. in Portsmouth, Virginia, on July 28, 1942. He was the son of Franchester “Chet” Brennaman, Sr. and Lillian (Skipwith) Brennaman. Growing up in Portsmouth, Brennaman was a right fielder for his Little League team and played high-school basketball. Though Brennaman enjoyed baseball (growing up listening to broadcasts of Nat Allbright doing re-creations of Brooklyn Dodgers games), sports were not the primary focus of his early life. Attending Woodrow Wilson High School in Portsmouth, Brennaman aspired to be an actor. After his high-school graduation, he studied at Randolph-Macon College in Ashland, Virginia and at the University of North Carolina.

Though Brennaman participated in the University of North Carolina drama program and performed in summer stock, by the time of his graduation in 1965, he had put acting aside. By this time Brennaman had a wife (Brenda) and two children, Thom and Dawn. Shortly after graduation, Brennaman was hired by a High Point, North Carolina, television station to work on the morning news show and occasionally substitute for the sports anchor. Six months later Brennaman left the television station to work at radio station WSTP in Salisbury, North Carolina.

It was at WSTP that Brennaman got his first taste of sports play-by-play when he broadcast a high-school football game in Spencer, North Carolina. Broadcasting football games on Friday nights, Brennaman also became the voice of the Catawba College Indians football and basketball broadcasts. He also began his baseball broadcasting career, describing Rowan County American Legion games. “I did as much play-by-play as any human could conceivably do,” Brennaman said later. “I did 25 high-school and college football games, and I did over 80 basketball games a year and American Legion Baseball.”3 Brennaman credited the experience with helping to develop his talents: “Everything that’s happened for me happened because of Salisbury.”4

After five years of broadcasting in Salisbury, Brennaman was hired by radio station WTAR in Norfolk, Virginia. While there he provided play-by-play for the American Basketball Association Virginia Squires. Norfolk also provided Brennaman with his first opportunity to do minor-league baseball play-by-play as he became the voice of the Triple-A Tidewater Tides, beginning in 1971. “It was against my better judgment to give a guy a job at the Triple-A level who’d never worked a full season of baseball,” Tides general manager Dave Rosenfield said later of hiring Brennaman. However, “his approach and desire were top-notch.”5 After just three seasons of broadcasting at the minor-league level, Brennaman was recommended by Rosenfield for the major leagues.

The Cincinnati Reds were looking for a new play-by-play radio broadcaster as the 1974 season approached. Al Michaels, who had covered the team for three seasons, had taken a job broadcasting for the San Francisco Giants. During winter baseball meetings in Houston, Rosenfield approached Dick Wagner, then assistant to Reds general manager Bob Howsam. “I’d heard Dick was looking for an announcer,” Rosenfield said. “I said, ‘I’ve got the best damn broadcaster around. If there’s a tape on your desk when you get back, will you listen to it?’ He said he would. I called Marty and told him to get that tape on Dick’s desk.”6 One of 220 applicants for the job, Brennaman was hired as the voice of the Reds.

Brennaman took the job knowing “Al Michaels is a tough act to follow.”7 Years later he recalled, “I remember the situation then was not ideal. Number one, I was succeeding a guy who was eminently popular in Al Michaels. Number two, I was broadcasting for fans who knew more about team history than I’ll ever know.”8 Brennaman did his first spring-training game from Bradenton, Florida, against the Pirates and felt that it went well enough that “the ghost of Al Michaels had disappeared.”9 The second spring-training broadcast was from Al Lopez Field in Tampa and Brennaman inadvertently began the broadcast by welcoming listeners to “Al Michaels Field.”10 Brennaman recalled, “I was embarrassed almost to tears.”11 Broadcast partner Joe Nuxhall turned to him during the commercial break and said, “I’ll be damned—we haven’t even begun the regular season and I already have material for the banquet circuit next fall.”12

The chemistry between Marty and former Reds pitcher Joe Nuxhall was evident from the start. Meeting for the first time in a Dayton, Ohio, photo studio for publicity shots before the season began, Brennaman greeted Nuxhall saying, “I have your baseball card.” Brennaman later reflected, “From that moment on we developed a one-of-a-kind relationship.”13 Working together for the next three decades, “Marty and Joe” became an institution in Cincinnati. In between pitches, the pair might chat about their tomato plants, their golf games, or anything else that might come to mind. “I think our success has to do with two things,” Brennaman explained. “First, we genuinely like each other. Second, we talk about stuff outside of baseball that people can relate to. We make fun of ourselves and we don’t take ourselves too seriously. I don’t know if our act would fly outside of Cincinnati.”14 The two became so closely linked in the minds of Reds fans that when Brennaman stopped into a grocery store near his home early one morning, a fan approached him to ask, “Where’s Joe?” Marty and Joe worked together until Joe’s retirement after the 2004 season. The two remained close friends until Nuxhall’s death in 2007.

In Brennaman’s first inning of regular-season play-by-play, Henry Aaron hit his 714th home run to tie Babe Ruth on the career list. During the commercial break, Nuxhall turned to him and said, “What the hell do you do for an encore?”15 Early that season, Brennaman would spontaneously utter what would become his signature call of a Reds win: “This one belongs to the Reds!” It was a phrase he said often during the early years, as the Reds won the World Series in 1975 and 1976. Assigned to cover the World Series each of those years for NBC radio and TV, Brennaman would not fully appreciate the team’s talent and accomplishments until years later: “I agree with what Bob Howsam said in the clubhouse at Yankee Stadium after the fourth and final game of the 1976 World Series. He said that in our lifetime we’ll never see another team the equal of this one.”16

Brennaman’s style evolved over the years. At the beginning he was, in his own words, an “unmitigated homer.”17 In 2000 he admitted, “When I hear tapes from back then, it’s the most embarrassing thing in the world.”18 Originally referring to the Reds as “we” and “our side,” Brennaman dropped the references to “we” after a player asked him how many hits he had had that day. Eventually Brennaman became known for his blunt assessments of the play in front of him. “I’m like a bull in a china shop. If a guy doesn’t run out a groundball or loafs going after a ball hit in the gap, I’ll say it,” he said.19 His candor wasn’t always appreciated by the players. In 1985 Dave Concepcion threatened to punch Brennaman in the nose for criticizing him. In 2000 Ken Griffey, Jr. took issue when Brennaman accused the outfielder of loafing during his first year with the Reds. “I am just not concerned about what they think,” Brennaman commented. “I know there are guys down there that don’t like me. That’s fine with me. There are a lot of guys down there I don’t like.”20 For Brennaman, maintaining his credibility with the fans was most important. “I’m probably more critical than any other baseball play-by-play announcer in the business, and I think that when I walk away from this job, the only thing I will have is a measure of credibility.”21

One person who didn’t appreciate the broadcaster’s candid approach was Reds general manager Dick Wagner. By the early 1980s, with the Big Red Machine largely dismantled, Wagner objected to Brennaman’s criticism of the team and added a third broadcaster to the radio booth. “In 1980, he put Dick Carlson with Joe and me for a few games to make it a three-man booth,” Brennaman said. “It was done because I was critical of the club and that was Wagner’s way of warning me.”22 Brennaman was so angered that he “spent three days trying to get fired” and “called Dick Wagner everything known to man to every writer who covered the club.”23 In early 1983 Brennaman asked Wagner for a contract extension and was refused. Brennaman was sure that he would be fired by the end of the season. Instead, Wagner was fired in July. Brennaman stayed with the team and never again had an issue with team management objecting to what he said on the air.

Though team management would no longer object to Brennaman’s criticism, commentary by Marty and Joe got the attention of National League President Bart Giamatti in 1988. On April 30, during a game against the Mets at Riverfront Stadium, manager Pete Rose argued with first base umpire Dave Pallone about a delayed call at the bag with two outs in the top of the ninth inning, which allowed New York to score the game’s winning run. After Rose was ejected, the heated exchange between the manager and umpire continued. Rose shoved Pallone twice, and subsequently earned a $10,000 fine along with a one month suspension for his part in the incident. On the air Brennaman called Pallone “incompetent” and a “horrible” umpire while Nuxhall, recalling Pallone’s work during a 1979 umpire strike, called him a “scab.”24 Fans, reacting to the umpire’s call and the ensuing altercation, threw radios, golf balls, and other objects onto the field. Pallone was forced to leave the game before it ended. Giamatti blamed Brennaman and Nuxhall for “inciting the unacceptable behavior of some fans.”25 Days later, the broadcasters met with Giamatti and Commissioner Peter Ueberroth for a meeting about the incident. “There was no indication they were trying to censure us. It was a discussion of what they felt was improper,” Brennaman said after the meeting.26 In retrospect he characterized some of their on-air statements during the game as “inappropriate,”27 but years later, he insisted, “They accused us of inciting a riot. I don’t think we did then and I don’t think we did now.”28

Admittedly a “college basketball freak,”29 by the late 1980s, Brennaman was spending his winters broadcasting college basketball. He provided play-by-play for Atlantic Coast Conference Games and covered NCAA tournaments for CBS radio. He partnered with Larry Conley to work on telecasts of University of Kentucky basketball from 1987 to 1990.

In the course of his career, Brennaman has covered many historic moments in Cincinnati baseball history, including the Reds’ 1990 World Series win, Tom Browning’s perfect game in 1988, no-hitters by Tom Seaver in 1977 and Homer Bailey in 2012, and Ken Griffey, Jr.’s 500th home run in 2004 and 600th home run in 2008. However, Brennaman’s “single most exciting moment” in the game came on September 11, 1985, when Pete Rose broke Ty Cobb’s record to become the all-time base-hit leader. “Everybody knew it was just a matter of time. But when it happened it was just overwhelming,” Brennaman recalled.30 When Rose was banned from baseball for betting on games in 1989, Brennaman insisted that he still deserved recognition by the Baseball Hall of Fame. Brennaman’s support of Rose’s reinstatement never wavered. In 2011 Brennaman said, “He bet on baseball. There’s no question about that. He admitted it in a book a few years ago. But if they’re going to allow these guys who are either confirmed or alleged, druggies … steroid users … just to be on the Hall of Fame ballot, which they are … then damn it, Pete needs to be on there too.”31

Though Brennaman and his wife, Brenda, divorced shortly after his arrival in Cincinnati, their son Thom recalls having a “terrific childhood.”32 Unlike most children, when Thom went to visit his father at work, he also got to meet such stars as Pete Rose, Johnny Bench, and Joe Morgan. Marty later remarried. He and his second wife, Sherri, had a daughter, Ashley. Reflecting on it, Marty said he felt he was a “much better father” to Ashley than he had been able to be to Thom and Dawn during the more hectic early years of his career.33 Though Thom Brennaman understood how difficult the travel and long absences could be for a broadcaster and his family, he chose to follow his father’s career path.

Thom Brennaman made his major-league broadcasting debut in 1989 providing play-by-play on Reds telecasts. In 1990 he moved to the Chicago Cubs booth and eventually went on to provide play-by-play for the Arizona Diamondbacks and for Fox Sports. In 2007, Thom Brennaman returned to Cincinnati to work with his father on Reds radio. Thrilled with the working arrangement, Marty said that working with his son was “a dream fulfilled.”34 That year Thom and Marty worked about 90 games together on radio (with Thom moving to TV duties on Fox Sports Ohio for many of the remaining games.) They are the only father-and-son baseball broadcasters to have each broadcast a perfect game (Marty called Tom Browning’s, Thom broadcast Randy Johnson’s in 2004), a world-championship team (Thom broadcast for the 2001 Arizona Diamondbacks), and a 20-strikeout game (both were broadcasting when Randy Johnson struck out 20 Reds batters in 2001).

“After three years I expected Marty to move on because of his expertise and the way he handled things,” Joe Nuxhall once admitted.35 Though Brennaman had several offers from other teams in larger markets over the years, he preferred to stay in Cincinnati and became just as identified with the team as Sparky Anderson, Johnny Bench, or Joe Nuxhall. Recognizing what an institution the broadcaster had become in Cincinnati, the Reds symbolically retired his microphone (similar to retiring a player’s uniform number) in a 2007 ceremony. By that year, Brennaman (at the advice of friend Vin Scully) cut back on his schedule, taking off 20 games during the season. In 2010 Brennaman said that he could “conceivably work indefinitely, as long as my health permits.”36 He continued calling games in Cincinnati for another decade, announcing that he would retire at the end of the 2019 season, his 46th year as the voice of the Reds.

Last revised: May 1, 2019

An earlier version of this biography is included in the book “The Great Eight: The 1975 Cincinnati Reds” (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Mark Armour. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Sources

Silvia, Tony. Fathers and Sons in Baseball Broadcasting: The Carays, Brennamans, Bucks and Kalases (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2009).

Associated Press. “And this honor belongs to Marty.” Charleston (West Virginia) Daily Mail, February 4, 2000.

Associated Press. “Brennamans will team up in Cincinnati.” Lexington (Kentucky) Herald-Leader, October 5, 2006.

Associated Press. “Concepcion threatens broadcaster.” San Jose (California) Mercury News, September 8, 1985.

Associated Press. “Marty Brennaman signs 3-year contract extension.” Lima (Ohio) News, August 10, 2007.

Associated Press. “Reds’ broadcasters apologize for remarks about ump.” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 4, 1988.

“Bench resigns from radio show with Brennaman.” Lexington Herald-Leader, July 28, 2000.

Bogaczyk, Jack. “Brennaman sees potential this season for the Reds; announcer says he has never been as optimistic about any other year.” Charleston Daily Mail, April 9, 2010.

Brennaman, Marty and Lonnie Wheeler. “Marty’s story.” Cincinnati Post, July 22, 2000.

Clay, John. “No identity crisis in Reds’ radio; duo wants to be called just Marty and Joe, and you can leave off Brennaman, Nuxhall.” Lexington Herald-Leader, July 7, 1990.

Fernandes, Doug. “Brennaman, McCoy covered Reds since early ’70s.” Sarasota (Florida) Herald-Tribune, March 22, 2009.

“Brennaman, Franchester Sr.” (obituary). Norfolk (Virginia) Virginian-Pilot, March 29, 1993.

Goldblatt, Abe. “Reds’ Brennaman calls Bonds ‘a first-class jerk.’ ” Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, November 9, 1993.

Horrigan, Jeff. “Running Gag.” Cincinnati Post, March 30, 1998.

Hunter, Bob. “Reds resolve TV woes.” Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch, January 9, 1987.

Jones, David. “Reds fans call ‘foul’ at announcers’ split.” Columbus Dispatch, April 10, 1986.

Katz, Marc. “Spat splits Marty, Johnny.” Dayton (Ohio) Daily News, July 28, 2000.

Koch, Bill. “Brennaman emotional at Hall ceremonies.” Cincinnati Post, July 24, 2000.

Lancaster, Marc. “Marty ad-libbed call.” Cincinnati Post, June 21, 2004.

Leffler, Bill. “Announcer recalls that first major mistake; the Reds’ voice remembers that Al Michaels was always on his mind during a big game.” Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, February 21, 1993.

“Lillian E. Brennaman.” (obituary). Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, May 16, 2003.

McCoy, Hal. “Brennamans a pair of ‘perfect’ announcers.” Dayton Daily News, May 21, 2004.

McCoy, Hal. “Marty on Joe: ‘People genuinely loved him’ – Brennaman says his longtime radio partner was the No. 1 figure in Cincinnati Reds history.” Dayton Daily News, November 17, 2007.

McCoy, Hal. “Nervous Marty signs on with his son.” Dayton Daily News, March 2, 2007.

“NSSA Weekend: Marty Brennaman comes back to Salisbury.” Salisbury (North Carolina) Post, May 1, 2005.

Paeth, Greg. “Brennaman may return to Reds’ TV broadcasts.” Cincinnati Post, November 30, 1993.

Paeth, Greg. “The Voices of the Reds—Baseball’s ‘odd couple’ Marty and Joe.” Cincinnati Post, October 2, 1990.

Peterson, Bill. “Twenty-five years of Marty and Joe.” Cincinnati Post, June 6, 1998.

Radford, Rich. “Brennaman named to Baseball Hall of Fame.” Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, February 4, 2000.

Raissman, Bob. “From the booth to the Hall.” New York Daily News, July 18, 2000.

Reed, Billy. “Brennaman to become Cats’ TV play-by-play man.” Lexington Herald-Leader, July 28, 1987.

Reed, Billy. “Marty and Joe blend together like beer, brat.” Lexington Herald-Leader, March 31, 1998.

Robinson, Tom, “Brennaman appreciates life with the Reds.” Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, October 13, 1990.

Robinson, Tom, “Brennaman talks his way into Fame; Reds radio announcer from Portsmouth goes into Baseball Hall of Fame today,” Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, July 23, 2000.

Rosecrans, C. Trent. “Father to son to fans—now it’s ‘Dad’ and Thom, and a new tradition.” Cincinnati Post, March 2, 2007.

Rosecrans, C. Trent. “Mike’s retired, but not Marty.” Cincinnati Post, June 11, 2007.

Schuman, Duane. “Marty and Joe keep livin’ on the air in Cincinnati.” Fort Wayne (Indiana) News-Sentinel, October 1, 1993.

Smith, Bill. “Brennaman, Reds’ ‘Voice,’ Young, Enthusiastic, Good.” Charleston Daily Mail, January 31, 1974.

Stein, Ray. “Brennaman’s first choice: Remain in Reds country.” Columbus Dispatch, March 11, 1988.

Stevens, Rich. “Brennaman not afraid to speak his mind.” Charleston Daily Mail online, February 7, 2011 ( http://www.dailymail.com/Sports/RichStevens/201102070063 ).

Strauss, Joe. “Duncan calls remarks classless; Notebook: Pitching coach was reacting to comments by Reds broadcaster Brennaman.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 18, 2011.

Tipton, Jerry. “ ‘This one belong to Cats’? Brennaman says it’s taken.” Lexington Herald-Leader, October 25, 1987.

Tolliver, Lee. “A hero’s welcome; Reds broadcaster Brennaman is deeply touched as he is honored at the Portsmouth Jamboree.” Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, February 9, 2001.

Williams, Marty. “ ‘Understanding each other’ is the key—The two have broadcast more than 4,000 Reds games over the last 24 years.” Dayton Daily News, April 1, 1997.

Woody, Paul. “Game announcers can speak freely—up to a point.” Richmond (Virginia) Times-Dispatch, May 5, 1988.

Notes

1 Marc Katz, “Spat splits Marty, Johnny,” Dayton (Ohio) Daily News, July 28, 2000.

2 Bill Koch, “Brennaman emotional at Hall ceremonies,” Cincinnati Post, July 24, 2000.

3 Greg Paeth, “The Voices of the Reds—Baseball’s ‘odd couple’ Marty and Joe,” Cincinnati Post, October 2, 1990.

4 “NSSA Weekend: Marty Brennaman comes back to Salisbury,” Salisbury (North Carolina) Post, May 1, 2005.

5 Rich Radford, “Brennaman named to Baseball Hall of Fame,” Norfolk (Virginia) Virginian-Pilot, February 4, 2000.

6 Tom Robinson, “Brennaman talks his way into Fame; Reds radio announcer from Portsmouth goes into Baseball Hall of Fame today,” Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, July 23, 2000.

7 Bill Smith, “Brennaman, Reds’ ‘Voice’, Young, Enthusiastic, Good,” Charleston (WestVirginia) Daily Mail, January 31, 1974.

8 Duane Schuman, “Marty and Joe keep livin’ on the air in Cincinnati,” Fort Wayne (Indiana) News-Sentinel, October 1, 1993.

9 Marty Brennaman and Lonnie Wheeler. “Marty’s story.” Cincinnati Post, July 22, 2000.

10 “Marty’s story.”

11 “Marty’s story.”

12 “Marty’s story.”

13 Hal McCoy, “Marty on Joe: ‘People genuinely loved him’ – Brennaman says his longtime radio partner was the No. 1 figure in Cincinnati Reds history,” Dayton (Ohio) Daily News, November 17, 2007.

14 Jeff Horrigan, “Running Gag,” Cincinnati Post, March 30, 1998.

15 Doug Fernandes, “Brennaman, McCoy covered Reds since early ’70s,” Sarasota (Florida) Herald-Tribune, March 22, 2009.

16 “Marty’s story.”

17 “Brennaman talks his way into Fame.”

18 “Brennaman talks his way into Fame.”

19 “Marty’s story.”

20 “Brennaman talks his way into Fame.”

21 “Marty’s story.”

22 “Marty’s story.”

23 “Brennaman talks his way into Fame.”

24 Associated Press. “Reds’ broadcasters apologize for remarks about ump,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 4, 1988.

25 “Reds’ broadcasters apologize.”

26 “Reds’ broadcasters apologize.”

27 “Reds’ broadcasters apologize.

28 Associated Press, “And this honor belongs to Marty,” Charleston Daily Mail, February 4, 2000.

29 Jerry Tipton, “ ‘This one belong to Cats’? Brennaman says it’s taken.” Lexington (Kentucky) Herald-Leader, October 25, 1987.

30 Bill Leffler, “Announcer recalls that first major mistake; the Reds’ voice remembers that Al Michaels was always on his mind during a big game,” Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, February 21, 1993.

31 Rich Stevens, “Brennaman not afraid to speak his mind,” Charleston Daily Mail online, February 7, 2011 ( http://www.dailymail.com/Sports/RichStevens/201102070063 )

32 “Brennaman talks his way into Fame,”

33 “Brennaman talks his way into Fame.”

34 Associated Press, “Brennamans will team up in Cincinnati,” Lexington Herald-Leader, October 5, 2006.

35 C. Trent Rosecrans, “Mike’s retired, but not Marty,” Cincinnati Post, June 11, 2007.

36 Jack Bogaczyk, “Brennaman sees potential this season for the Reds; announcer says he has never been as optimistic about any other year,” Charleston Daily Mail, April 9, 2010.

Full Name

Franchester Martin Brennaman

Born

July 28, 1942 at Portsmouth, VA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.