Walter Ball

Right-hander Walter Ball was one of the top pitchers in early black baseball, often being favorably compared with a contemporary, Hall of Famer Rube Foster. In the prime of his career, the Indianapolis Freeman remarked, “everyone knows that Walter Ball and ‘Steel Arm’ Johnny Taylor are the most sensational pitchers of the race.”1 Lacking great speed, Ball found success with his smarts, control, and frequent use of the spitball. Off the field, the stylish Ball had a reputation as a gentleman and “the swellest dresser,”2 often wearing tailored suits.

Right-hander Walter Ball was one of the top pitchers in early black baseball, often being favorably compared with a contemporary, Hall of Famer Rube Foster. In the prime of his career, the Indianapolis Freeman remarked, “everyone knows that Walter Ball and ‘Steel Arm’ Johnny Taylor are the most sensational pitchers of the race.”1 Lacking great speed, Ball found success with his smarts, control, and frequent use of the spitball. Off the field, the stylish Ball had a reputation as a gentleman and “the swellest dresser,”2 often wearing tailored suits.

Walter Thomas Ball was born September 13, 1877, in Detroit to John M. and Ella (Swift) Ball. When he was eight years old the family moved to St. Paul, Minnesota. John Ball worked as a barber and also as a Pullman porter. The Minnesota census of 1895 does not list any brothers or sisters for Walter.

Numerous sources give a different birth date and incorrectly list his full name as George Walter Ball with the nickname “The Georgia Rabbit.” Detailed research by Gary Ashwill3 revealed that in Sol White’s History of Colored Base Ball, published in 1907, a comma was misplaced in a listing of pitchers, and Ball was mistakenly confused with another pitcher named George Washington. The first name, George, and the nickname “Georgia Rabbit,” were mistakenly attached to Walter Thomas Ball instead of Washington, who was in fact from Georgia.

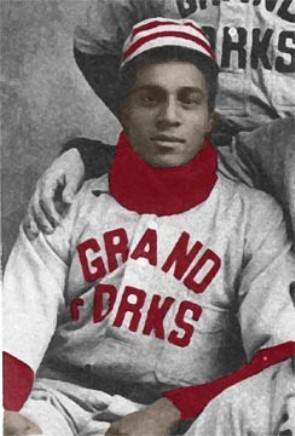

In his teens, Ball began playing on the sandlots of St. Paul and by the late 1890s was pitching for the Young Cyclones, a top amateur team in the city. He also played briefly for a team in Osceola, Iowa. In early 1900 he signed with a club in Devils Lake, North Dakota, and later that summer joined the Grand Forks, North Dakota, club in the independent North Dakota league. He reportedly won 25 of 28 games and led the team to the state championship.4

In 1900 he married18-year old Cora Ray. He left the Grand Forks club briefly in July and traveled to St. Paul, Minnesota for the birth of their son Wendell on July 23, 1900. In August of that year a local fan offered Ball “a new pair of baby shoes for the young heir of his for every man he struck out after the game had progressed a few innings.”5 Wendell died at the age of three, on April 29, 1903 “following a brief illness.”6

Walter and Cora must have spent the winter of 1900-1901 in Grand Forks as it was reported that in late December the couple attended a holiday celebration for the “Colored People” of the city.7 During the winters Ball, like his father, worked as a sleeping car porter on the railroad. He joined the Grand Forks club again in 1901 but played in several other locations as well. There are reports of him pitching for teams in York and Lakota, North Dakota (small towns about 60 miles west of Grand Forks) as well at as least one game for Park Rapids, Minnesota and an “all-Indian team” in Akely, Minnesota.

In the spring of 1902, Ball signed with Duluth, Minnesota but the team disbanded shortly thereafter when the ministers of the city threatened “unremitting warfare against Sunday baseball.” He then planned to rejoin his former club in Grand Forks, but that team had now joined the new Northern League. Although it was an independent league and not technically subject to the National Agreement, the league still honored the color line in place in Organized Baseball, and Ball was told by Grand Forks management that he was not wanted. Instead he joined a semi-pro team in St. Cloud, Minnesota and helped them to the championship of eastern Minnesota.

The Balls returned to their home in Grand Forks in the off-season and that winter he was approached by Frank Leland, owner of the Chicago Union Giants. He also received offers from a team in Stillwater, Minnesota and the Page Fence Giants before signing with Leland. The Giants were the first all-black team Ball played on; until then he had been one of the few, and usually the only, black player on white teams.

Characteristic of many of the early players in black baseball, Ball spent the next several years jumping between numerous teams. His play with the Union Giants attracted the attention of E.B. Lamar, manager of the Cuban X-Giants of New York. Signing with Lamar, Ball went east for the 1904 season, then joined the Brooklyn Royal Giants for the first half of the 1905 season. That season he beat the National League’s Brooklyn Superbas 7-2, the first time a black team had ever defeated a white major league team. At midseason he returned west to reunite with Frank Leland and pitched for the newly formed Leland Giants. During the last half of the season, Ball’s hurling contributed significantly to a winning streak of forty-eight games.

In 1906 Ball went back to New York, this time with the Quaker Giants. When the team disbanded on July 1, he returned to Chicago, finishing the season with the Leland Giants. In 1907 Ball organized, managed, and played for the St. Paul (Minnesota) Colored Gophers, however, around the Fourth of July he again returned to Chicago to finish the season with Leland‘s team.

During the latter part of the season the Leland Giants played a series of games with a white All-Star club at the White Sox grounds. Often playing in the outfield when not pitching, Ball made a phenomenal catch in right field in the last game, saving the championship for the Leland Giants. That off-season would be the first of several he would spend in the Cuban Winter League. In the early part of 1908 he played for the Minneapolis Keystones, an all-black traveling team, but Leland again succeeded in getting Ball to return to his team, securing Ball’s release from the Keystones. The highlight of the season for Ball came in a game in which he was playing right field. With Rube Foster holding a 1-0 lead in the seventh inning, he caught a line drive and threw a runner out at the plate, preserving the victory for the Giants.8

The 1909 season was arguably the best of Ball’s career. Chicago writer James H. Smith called him the “premier twirler of the year.”9 When the Cuban winter league closed in March, Ball joined the Leland Giants for spring training in Memphis, Tennessee. Barnstorming north he was undefeated. During the season he pitched in 25 games with a 12-1 record, 70 strikeouts, 34 walks, 12 hit batsmen, and 1 wild pitch. He batted .238 for the Chicago City League champions.

The St. Paul Colored Gophers challenged the Giants to a series to determine the Western Colored Championship. Giants’ manager Rube Foster was injured and unable to pitch, so the burden fell on Ball and Pat Dougherty. Ball pitched in two games but lost his only decision in the Lelands’ defeat.

To end the 1909 season the Leland Giants scheduled a three game exhibition series against the Chicago Cubs. In the opening game October 18, Ball faced Three-Finger Brown, who was coming off a 27-win, 1.31-ERA season. Cubs’ catcher Jimmy Archer and first baseman Frank Chance, refused to play against black players and did not participate in the game. Ball lost 4-1 due to six Giant errors that contributed to three unearned runs.10

When owner Frank Leland and manager Rube Foster split in 1910, Ball remained with Leland and hit .359 for Leland’s new team, the Chicago Giants, but injured his knee late in the season

Around this time Ball got involved in the performing arts, joining the Pekin Stock Company, a touring black musical and comedy theatre group based in Chicago. He planned to go into vaudeville when his pitching arm gave out.11 During a private performance, Ball recited a monologue entitled “His Famous Play in the Star Game at White Sox Park” in which he recounted his game saving catch and throw preserving Foster’s victory over the white all-stars. A review in the Indianapolis Freeman’s “Musical and Dramatic” section noted, “Ball closed the bill and all pronounced him a success.”12

He remained with Leland’s Giants in 1911, but left Chicago the next few seasons. In 1912 he pitched with the St. Louis Giants, where he reportedly won 23 straight games. He then went back east, pitching for the Brooklyn Royal Giants and briefly with the Schenectady Mohawk Giants in 1913 and the New York Lincoln Giants the following year. One of his top pitching performances came while playing with Brooklyn in 1913. He beat a white club from Trenton, New Jersey 2-0, striking out 15, in a game reputed to have lasted only 53 minutes, recognized as a record at the time.13

Frank Leland died in 1914, and as a testament to Ball’s status among black baseball circles in Chicago, he was a pall bearer at the funeral. In 1915 he reunited with Rube Foster and was back in Chicago with the American Giants. That spring Foster took his team to California for exhibition games against white teams. On the trip Ball defeated two future major leaguers, Stan Coveleski and Dutch Leonard of the Pacific Coast League champion Portland Beavers. However, now in his late thirties, Ball was on the downside of his career and one report referred to him as “previously one of the premier pitchers in black baseball.”14

When the original Negro National League was formed in 1920, Ball was over 40 years old and nearing the end of his career. Over the next few years Ball pitched with several lesser Chicago-area teams, including the Chicago Giants, who were in their declining years. In the mid-1920s he formed his own traveling team, the “Walter Balls,” and hired a young, unknown promoter named Abe Saperstein to schedule his team’s games. In 1935 and 1936 Ball was selected as a coach for the West squad in the early East-West Black All-Star games in Comiskey Park in Chicago and in 1938 was hired to manage the semi-pro Columbia Giants in the Chicago Midwest League.

Ball was one of several early black pitchers who many thought would have played in the major leagues had the color line not been in place.15 As mentioned earlier, he had the opportunity to play against white major leaguers on several occasions. During his lengthy career, Ball played with and against the best black players of the era. In addition to Rube Foster, teammates included star pitchers Bill Gatewood and Hall of Famer Smokey Joe Williams. Bruce Petway and Chappie Johnson were often Ball’s catchers.

In his later years one source indicated he worked as a custodian, while another said he was employed by the Chicago Sports Association. In 1941 he was listed as an employee, with the job title “recreation, athletics”, with the Chicago Baptist Institute.16 Ball died December 16, 1946 at Cook County Hospital in Chicago after an unspecified lingering illness at the age of 69. He was buried in an unmarked grave, said to be near where Rube Foster is interred, at Lincoln Cemetery in Blue Island, Illinois. He was survived by his wife Jeanette and his four living children. Ball was proposed as a Hall of Fame candidate in 2006, but failed to make the first round of cuts by the Negro Leagues Special Committee.

Family history for Ball is sketchy. Census and other historical records often confused him with George Walter Ball, and possibly another Walter Ball who also lived in Chicago. The best information available is that he had at least five children and possibly four marriages. In addition to his marriage to Cora, which produced his first son Wendell, Ball was also married to Ethel Motley. A son, Elwen, born in 1912, became. a decorated member of the US Navy during WWII. Sometime in the teens Ball married Rosetta King17 and they had three children, a son Charles, and two daughters, Jean and Judith. His last marriage was to Jeanette, but no record could be found of when this marriage took place or of them having children.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to recognize the assistance provided by SABR member Al Yellon in researching information for this biography.

Sources

Steven R. Hoffbeck, Swinging for the Fences: Black Baseball in Minnesota, Minnesota Historical Society, 2005, Jim Karn , “Drawing the Color Line on Walter Ball, 1890-1908

http://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?ID=36

Larry Lester, Rube Foster in His Time: On the Field and in the Papers with Black Baseball’s Greatest Visionary, McFarland, Aug 31, 2012

Leslie A. Heaphy, Black Baseball and Chicago:Essays on the Players, Teams, and Games of the Negro Leagues’ Most Important City, McFarland, Jan 1, 2006

Robert Charles Cottrell, The Best Pitcher in Baseball: The Life of Rube Foster, Negro League Giant, NYU Press, 2004

Todd Peterson, Early Black Baseball in Minnesota: The St. Paul Gophers, Minneapolis Keystones, and Other Barnstorming Teams of the Dead Ball Era, McFarland, 2010

James A. Riley, Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994, Ball, George Walter, pages 47-48.

Stew Thornley, Baseball in Minnesota: the Definitive History, Minnesota Historical Society, 2006.

John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues, Hastings House Daytrips Publishers, 1998.

Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game 1933-1953, University of Nebraska Press, 2001.

William F. McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season: Pay For Play Outside of the Negro Leagues, McFarland, 2007.

Fay Young, “Walter Ball, Famous Pitcher, Dies in Chicago”, Chicago Defender, December 21, 1946

Sol White’s History of Colored Base Ball, with Other Documents on the Early Black Game, 1886-1936, republished by University of Nebraska Press, 1996

Notes

1Indianapolis Freeman, April 16, 1910

2Riley

4Hoffbeck

5Grand Forks (ND) Daily Herald, August 3, 1900

6Grand Forks (ND) Daily Herald, April 30, 1903

7Grand Forks (ND) Daily Herald, December 18, 1900

8 Young

9Indianapolis Freeman, September 25, 1909

10 Young

11 Peterson, page 207

12Indianapolis Freeman, May 28, 1910

13 Young

14 Cottrell, page 87

15 White

16Chicago Defender, January 25, 1941

17 McNeil, page 16

Full Name

Walter Thomas Ball

Born

September 13, 1877 at Detroit, MI (US)

Died

December 16, 1946 at Chicago, IL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.